There is no question that the banking industry in Europe and North America has reached a turning point. Interest rates are up, but so is inflation. And after the longest bull market in history, uncertainty and doubt have replaced optimism in most major markets.

While many financial institutions today are hopeful that rising interest rates will mark a return to the good old days when profitability was more assured, this is no time for complacency. The bottom-line benefit from growth in net interest income (NII) could be offset—or even exceeded—by rising operating costs and an adverse risk outlook. At the same time, many of the pressures that banks have been operating under during the past several years will persist, owing to the regulatory environment and intensifying competition.

The winners over the next few years will be the banks that face these realities head on—using the tailwinds provided by the improving interest rate environment to fund a transformation that for many institutions is long overdue.

Death by a Thousand Cuts

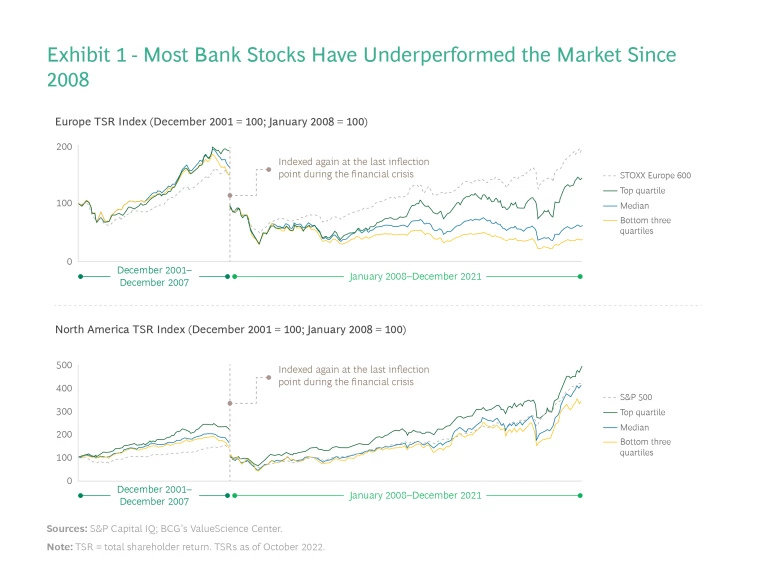

Before 2008, banking was a very profitable industry. Looking at a sample of the 15 largest banks by assets in Europe and North America shows that they consistently delivered a return on equity (RoE) after tax of about 15%. Total shareholder returns (TSRs) also consistently exceeded those of the market (specifically, the STOXX Europe 600 and the S&P 500).

The financial crisis changed all that. RoE briefly turned negative to about –2% in Europe and North America in 2008 and remained low for the next 13 years. In 2020 and 2021, the average RoE was just 5% in Europe and 10% in North America.

As a result, almost no European bank has come close to matching the TSR delivered by the STOXX Europe 600 in recent years. (See Exhibit 1.) Although North American banks fared significantly better than their European counterparts, with the median TSR closely tracking the S&P 500, only the top quartile are outperforming the market.

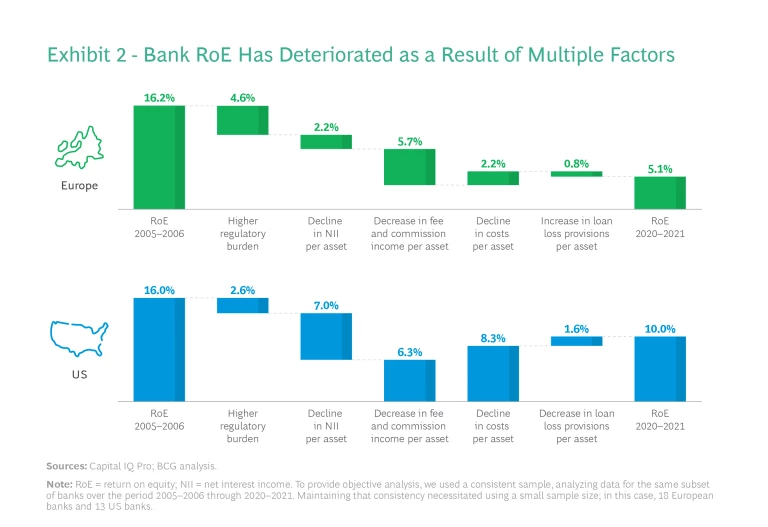

Banking’s long slump is the result of several multifaceted factors. This is evident by taking a look at a subset of European and US banks. (See Exhibit 2.)

Both Europe and the US have experienced an extended period of abnormally low interest rates. This led to a perceptible drop in NII. Central bank interventions to support stability, such as the European Central Bank’s introduction of targeted longer-term refinancing operations, provided a buffer. But these measures were not enough to shore up NII fully. However, while the adverse interest rate environment is often presented as the primary reason for banks’ depressed performance, the picture is more complex.

Other factors that played a large role include regulatory changes that required banks to maintain higher levels of capital and liquidity. These mandates improved the financial system’s resilience, but they eroded bank profitability. Tighter regulations also triggered a collapse in investment banking and capital markets activities and the associated fees. From 2006 through 2021, banks’ relative balance sheet volume of derivative and trading assets fell by 10 to 15 percentage points.

Faced with these pressures, banks tried to bring costs to a level commensurate with their new income level. But compliance and regulatory costs continued to rise, and most banks had to funnel significant investment into acquiring digital capabilities to keep up with an evolving market. Progress on cost containment was especially muted in Europe, compared with the US, where banks took more decisive action. A cutthroat competitive environment in both constrained banks from passing cost increases on to their customers.

The question now is whether rising rates will provide banks with enough lift to reset after this bruising period.

A Temporary Relief—Maybe

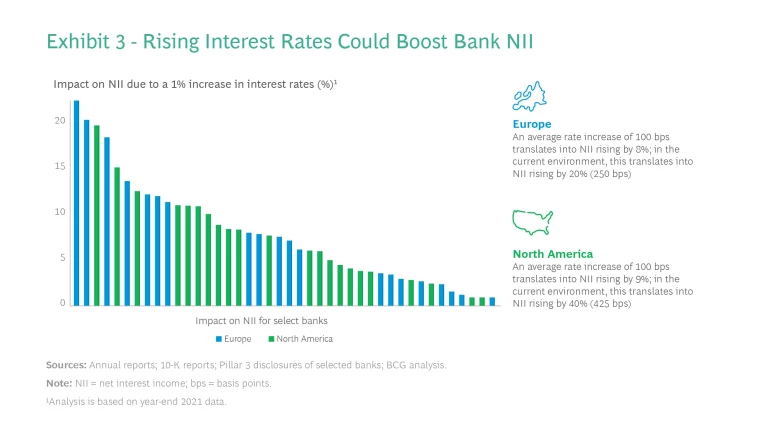

Interest rates are increasing meaningfully for the first time in more than a decade, with rates in Europe reaching 2.5% by year-end 2022—an increase of 250 basis points since June. And in North America, the US, for example, has seen the benchmark federal funds rate range climb to 4.25% to 4.50%, a rise of 425 basis points since March 2022. However, both Europe and North America remain locked in a cycle of spiraling inflation, with clear signs of an economic slowdown on the horizon. If inflation persists and the real economy does indeed slow down, banks will face a very complex operating environment.

Interest rates will provide short-term profit and loss relief. Banks’ NII could rise in Europe and North America by an average of 20% and 40%, respectively, on the basis of year-end 2021 data. (See Exhibit 3.) In simplified terms, this is happening because bank loans (and associated hedges) are repricing faster in the higher-interest environment than are savings and deposit accounts.

The fourth-quarter earnings reports for 2022 confirmed this picture. However, the returns will likely be greatest in the short term (6 to 12 months). Over time, customer and competitive realities will require banks to increasingly pass beneficial rates on to their account holders and adapt to greater volatility within their product portfolio, as customers move from noninterest-bearing accounts to term deposits. These effects will likely happen faster than in previous cycles because digital adoption has increased, giving customers greater transparency and making it easier for them to switch accounts or even banks. Higher lending rates will also likely curb demand for borrowing, offsetting some margin gains. This effect is already visible in some mortgage markets, including those in Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, the UK, and the US.

Inflation and a more muted macro outlook will exert pressure on profits and losses. Banks will feel the sting of inflation on their cost bases as rising prices push up wages and other operating costs (such as those for IT, data, and other third-party vendors). And after a bumper 2021 and a rocky 2022, a looming bear market could depress fee income. The prospect of a recession will also impact the risk outlook for banks, with the increased likelihood of defaults requiring institutions to make additional loan loss provisions. These countervailing pressures can easily eliminate most, if not all, of the relief generated by positive rates in the short-to-medium term.

For example, assuming banks gain the lift expected (NII rising by an average of 20% in Europe and 40% in North America), modestly bad news on inflation and market environments could wipe those gains out. All it would take is a slight increase in operating expenses by 5% to 10% (a similar order of magnitude as current inflation rates), a 5% to 10% reduction in fee income (returning to prepandemic levels of market activity), and an increase of loan loss provisions to 50% to 100% of 2020 levels (as a proxy for a potential downturn hitting balance sheets that have low levels of reserves).

What Banks Should Do Now

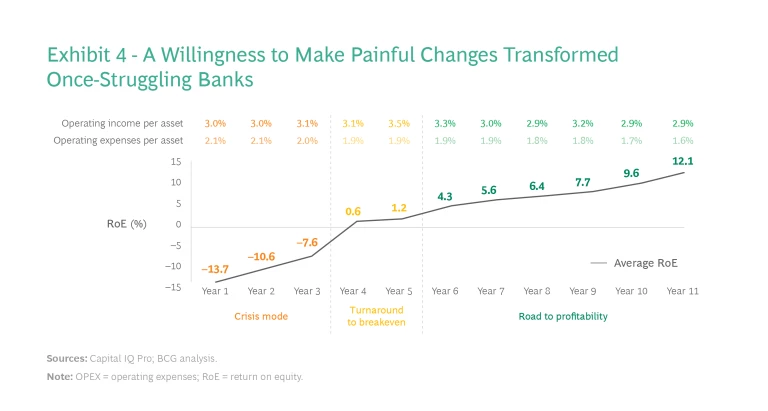

Because relief is likely to be short-lived, it is imperative for banks to use any breathing room afforded now to work on their performance. For inspiration, banks can consider the example of others that successfully turned their fortunes around over the past decade. We looked at a set of 14 deeply troubled banks—many of which were ultimately taken over by private equity firms. Over the course of five to ten years, these institutions grew average RoE from a low of about –14% to roughly 12%, putting these banks comfortably within range of the returns that were common before the 2008 financial crisis. (See Exhibit 4.)

What steps did these banks take to become profitable?

The first and most obvious action they took was to embrace efficiency. All banks doubled down on cost performance, taking a harder look at spending, simplifying and cutting slack wherever possible, and reaching for levers that could drive productivity higher. They were also disciplined when determining where to invest scarce resources (such as capital, liquidity, investment budgets, and full-time employees), making allocations on the basis of clear profitability hurdles, structurally improving revenue generation, and optimizing returns. Management refused to be complacent with current performance. They were uncompromising in making hard but necessary changes to improve their RoE trajectory, making tough decisions (including exits), relentlessly driving and managing performance, challenging entrenched practices, and crafting strategies that sought to balance feasibility and impact.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on business resilience

As banks look ahead, they can be inspired by the example of these once deeply challenged institutions and consider these steps:

- Decide where to play and grow, and determine where to exit. Banks must be brutally honest about their strengths and weakness and make a clear-eyed assessment of the businesses and markets where they have the ability to win and those where the competitive and capability barriers are too high. In the areas they choose, banks should aim to quickly reach critical scale and consider potential inorganic options to facilitate this.

- Reorient resource allocation to be in line with strategic priorities. Capital, liquidity, investment budgets, and operational resources must be stringently redeployed to fit with the bank’s new strategic priorities, and any investment initiative must clear high bars for profitability.

- Unlock the full revenue potential of businesses and markets. Banks need to make sure that they are maximizing cross-selling and prospecting opportunities with clients and targets, leaning hard into their sales and risk-management processes to keep the pipeline full of quality leads.

- Define a lean operating model and exert rigorous cost control. Taking a hard line on costs is imperative. Banks must review all activities in the light of their chosen strategic priorities and be relentless in rooting out nonessential spending.

- Buttress risk management. The current multifaceted environment brings unique complexities. High inflation and energy prices create second-order effects, making it more difficult to form predictions on the basis of past experience. And supply chain disruptions can create ripple effects that drag down healthy companies. Banks need to ensure that their risk management approaches, especially on the credit risk side, are strong enough to deal with these challenges. They may need to conduct advanced cash flow forecasting on the basis of transaction behavior, rather than by extrapolating from past experience. This can help them detect signs of credit deterioration in time to proactively intervene.

- Prioritize performance management and efficient execution. Bank leaders must be crystal clear about their financial objectives and set concrete targets and milestones, and management must be fully aligned on these targets and review performance assiduously, stepping in decisively to course correct whenever needed.

Banks have been in the throes of change since the financial crisis. But now they are reaching a turning point. The tailwinds from higher interest rates will likely provide temporary breathing room. But rising rates are no panacea for ailing performance. Winners will seize this moment and the brief respite it offers as an opportunity to alter course and accelerate a core transformation.