For some time now, higher-education leaders have recognized that the current approach to needs-based financial aid is hardly sustainable, for students or for schools. So the field is understandably hopeful about the prospect of developing financing options linked to student outcomes. Outcome-aligned student financing is a promising alternative that could make postsecondary education more accessible and affordable to students, while encouraging them to pursue in-demand career paths. For institutions, it offers a potential way to improve enrollments and completions by creating a distinctive value proposition. That’s especially relevant in an era marked by fewer first-time, full-time students and more competition for them than ever before.

Although a strategic approach is essential, few schools have grappled with the full implications of outcome-aligned student financing. Such financing comes in many flavors, and no single solution could conceivably meet all students’ needs. Higher-ed institutions must define their own strategic goals and then rigorously research and test financing options to find the right set to meet those goals. Then, institutions must figure out the best ways to implement alternative financing programs, appeal to their target student segments, and integrate the programs into enduring business models.

Current Financing Models Are Broken

The biggest challenge facing most higher-ed institutions (other than elite, selective ones) is gaining sufficient enrollment. In the battle for students, they must compete not only with other higher-ed institutions, but also with alternatives such as nondegree skills-focused programs. A growing number of would-be students are forgoing further education and training altogether to take advantage of today’s robust hiring environment in nontech industries.

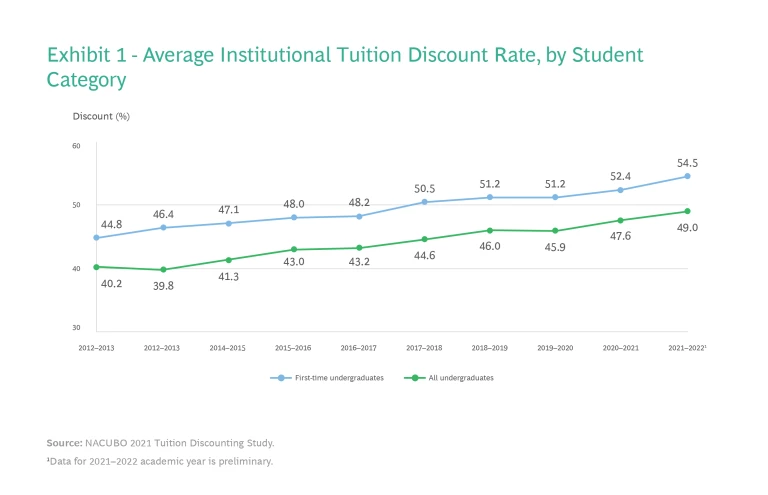

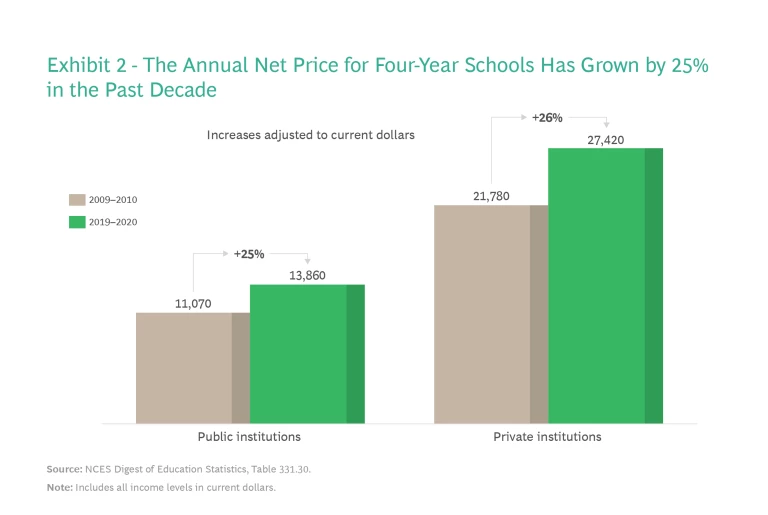

For many years, higher ed’s answer has been to discount the price of attendance. According to the National Association of College and University Business Officers, the average financial aid discount for first-time, full-time, first-year undergraduates reached 54% of nominal tuition rates in the 2020–2021 academic year—a record high. (See Exhibit 1.) Although generous discounts and aid awards encourage many students to enroll, these packages are often insufficient to cover students’ full financial need. In fact, after taking into account financial aid awards, the average net price charged by both public and private institutions has grown by 25% over the past decade. (See Exhibit 2.)

This may in part explain why nine out of ten schools do not fully disclose the cost of attendance.

Despite these net price increases, schools are faring no better. With costs (largely for personnel and facilities) rising and enrollments falling, schools spend more per student and cover less of that cost with tuition dollars. This situation is creating financial instability for many institutions.

By the end of 2021, total student loan debt in the US was nearing $1.75 trillion and still growing. The biggest loan risks are students who do not complete their degree; without it, they lack the promised earning power to repay their loans. Meanwhile, among graduates, there are countless stories of people struggling to chip away at their student debt decades after receiving their diplomas because of underemployment: working in fields that don’t require their level of degree and that offer correspondingly lower compensation. Some of this may be changing, though. Members of Gen Z—the first-time, full-time population currently enrolled in higher ed—increasingly focus on return-on-investment in their higher-ed choice and have a negative perception of student loans.

And yet despite these various efforts that financially undermine many institutions and students, the desired goals of increased access and enrollment continue to recede. Why? Certainly, shrinking demographics and the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on enrollment play prominent roles. But questions about ROI abound. Unlike demographics, which schools can do little to control, and discounting, which undermines sustainability, ROI is something that schools can affect—to the benefit of their graduates’ quality of life as well as their own enrollment numbers.

This helps explain higher education’s growing interest in outcome-aligned student financing: financing at least some portion of student repayments for tuition, room, and board through their employment and compensation as they progress in the working world. Whereas traditional loans force students to take on uncomfortable levels of risk, and financial aid shifts that risk onto educational institutions, outcome-aligned student financing distributes the risks and benefits more evenly between students and schools.

Over the past five years, outcome-aligned student financing has proliferated at coding bootcamps and other non–Title IV schools. Without a track record and without access to federally subsidized student loans, these organizations had to devise new ways to persuade students to enroll in their programs. In contrast, among degree-granting higher-ed institutions, outcome-aligned financing has developed in fits and starts. Income-sharing agreements (ISAs) gained initial momentum from two types of institutions: small, nonselective colleges seeking to convince students of the attractive ROI and boost enrollment, and large public schools aiming to improve completion rates for students who had exhausted their federal aid dollars, were reluctant to take out additional loans, or both. Yet Biden administration regulations reclassifying ISAs as loans have created strong headwinds for ISAs.

The Benefits and Challenges of Adoption

Outcome-aligned student financing (including ISAs) offer protection for students who pursue careers in fields that offer low starting salaries and for those who, after graduating, can’t find jobs that are relevant to their programs of study. Offering outcome-aligned student financing also enables universities to demonstrate their commitment to helping students build successful careers, which can be an appealing differentiator to students who are trying to decide where to enroll.

Schools must consider how to allocate their limited financial-aid dollars equitably. In an ideal world, no student would need to take a loan, but unfortunately a loan-free commitment is unrealistic for all but the handful of schools with the largest endowments. From an equity lens, schools award financial aid on the basis of the student’s family income history. In contrast, outcome-aligned student financing allows institutions to support students on the basis of the student’s current and future need. This lens permits schools to maximize the impact of their limited financial aid dollars. Optimizing financial aid awards while boosting enrollment could have significant benefits for college treasury departments.

Applying a Pricing Strategy Lens to Higher Ed

To fairly and thoroughly assess outcome-aligned student financing versus traditional loan-based options, we must compare their pricing models as well as the value they deliver.

The traditional list price/financial aid/loan model was designed to distinguish between families who can afford full tuition, those who can’t afford full freight, and Pell-eligible students who can scarcely afford to pay anything at all. The aid and loan components served as levers that schools could use to adjust costs for the latter two groups. The goal of this model was to promote intergenerational equity by effectively offering greater discounts for students and families with fewer resources.

In practice, however, traditional pricing at less selective schools has proved to be less equitable or effective than expected, for two reasons:

- Merit aid, which accounts for a large portion of financial aid awards at these schools, tends to go to students from wealthier families because wealth correlates with academic readiness—and by appealing to such students, schools improve their position in rankings of the academic caliber of their incoming class. As a result, lower-income and higher-income students often end up with similar discounts.

- Usually, the resulting total discounting across the traditional model either doesn’t cover the cost to serve or forces the school to cut costs. Thus, it reduces the perceived quality and value of the educational offer.

For elite schools, the current system preserves a competitive advantage. These schools are already highly selective, and students’ willingness to pay is high. As a result, wealthier students pay full tuition and rarely receive merit aid. And the schools’ large endowments enable them to largely meet the full need of students who require financial assistance.

For students who attend less selective schools, outcome-aligned student financing is better because it enables them to avoid loans altogether or to quickly pay them off. If implemented well, it also does a better job of offsetting schools’ cost to serve, allowing them to invest in the resources necessary to help their students succeed and recoup more in net present value, even if some payments are deferred to the future. Outcome-aligned financing provides a competitive advantage for most nonselective higher-ed schools, which tend to be more workforce-oriented than elite, research-oriented institutions are.

At two-year community colleges, there is no cost to attend and most students work while learning. Even so, the opportunity cost of attending community college is high in today’s economy. With just a high school degree, many students can get jobs in manufacturing or trades that pay more than community college graduates earn. The vast majority (80%) of community college students take more than two years to complete their program. That, along with mediocre compensation levels, family demands, and the opportunity cost risk of leaving their current jobs, explains why community college enrollment has dropped by nearly 20% since the pandemic began.

To determine whether a pricing model makes sense, we examine it on the basis of five factors:

- Alignment between the price charged and the value to the student

- Fairness and equity

- Whether the model recovers cost to serve (for the institution)

- How closely the model corresponds to competitive advantage

- How the model compares to the student’s next-best alternative

Applying this pricing model framework to nonselective four-year institutions, we compared the current traditional financial aid and loan model to the outcome-aligned student financing model. The results suggest that outcome-aligned student financing would be more effective.

A Cornucopia of Financing Options

In practice, there are many types of outcome-aligned approaches, including these:

- ISAs

- Loan insurance wrappers

- Employer-driven loan repayment (or loan repayment assistance programs)

- Employer stipends while in school

- Free shorter-form training for well-compensated, in-demand careers (sometimes known as “Hire-train-deploy”)

- Free courses and graduate school until a graduate secures BA-level compensation

In addition, governmental stakeholders offer several new options. The federal government continues to experiment with income-based repayment and income-driven repayment on federal loans. As of this publication’s release date, the Biden administration had proposed modifications to loan repayment programs and loan forgiveness, which are being implemented or are on hold pending legal challenges. Some states, including Oregon, have even examined the implications of providing free education funded by a tax on each graduate’s income, similar to the Australian model.

Employers can benefit from alternative financing mechanisms that draw more recruits from the higher-ed institution. Employers will sometimes guarantee employment to students who successfully complete their program and meet other criteria, with a commitment to fully pay down student debt over a prescribed period of time.

Nevertheless, most outcome-aligned student financing mechanisms are still new and largely untested. On top of that, each alternative financing structure has many variants. With so many options on tap, schools are often unsure about which ones to deploy. In some cases, university leaders may gravitate to a single model they know best, without fully considering all the options. This raises the question, how should schools select one or more financing programs that will boost demand among students, help stabilize school finances, and lead to effective engagement with employers? It’s a big—and pressing—question.

Identifying the Best Outcome-Aligned Options

Armed with greater clarity about the relative benefits and drawbacks of the pricing models and value of traditional versus outcome-based options, how can higher-ed institutions identify the outcome-aligned vehicles that are the most mutually beneficial? On the basis of our research of leading institutions, we suggest adopting five key practices: clarify the strategic goal for the program, target student segments, and understand how to pay for it; use market research and testing to assess loan appeal and uptake among target student segments; identify leading measures to track; make sure the business models can hold up; and design (and stick to) clear implementation plans.

Clarify the Strategic Goal for the Program, Target Student Segments, and Understand How to Pay for It

Consider these examples of goal clarification:

- Improve access and affordability for middle- and lower-middle-income families. Such families tend to be very price sensitive, demonstrating a low response rate to school acceptance offers when aid awards are insufficient to cover their student’s full needs. Some institutions have set aside a pool of funds raised directly from donors or pulled from their endowment as an “evergreen” way to offer break-even income-sharing agreements. Instead of spending down funds each year, as is the case with financial aid, these schools keep the principal intact and set up a “pay it forward” funding mechanism. This mechanism is based on ISAs with 0% market returns, where one cohort of graduates pays a portion of their new income back to the fund to support the next student cohort.

- Align strategic goals with on-the-ground financing mechanisms. Many leading law schools and other professional schools have explicit long-standing goals of encouraging more students to enter public service in lieu of joining companies. Despite this, many law students feel pressure to join the corporate world so that they can earn the high salaries they need to help pay off their large loan debts. The solution that many schools have adopted is to ask alumni to fund loan repayment assistance programs (LRAPs) that promise to repay the debts of graduates who devote themselves to public service.

- Demonstrate the ability to deliver successful employment outcomes. To improve perceived ROI and increase enrollment some higher-ed institutions have sought, without financing, to show prospective undergraduates they can deliver successful employment outcomes. Their challenge is to find a business model that allows them to implement this strategy without having to invest significant funds, given their limited free cash flow. One solution is to offer a job guarantee at a minimum salary. If a graduate can’t find employment or receives only job offers that fall below that salary level, the school offers additional courses for free to raise the student’s employment prospects. An institution’s per-semester costs for offering a set of academic courses are largely fixed, so schools incur few financial risks by instituting outcome-aligned programs that promise students free access to master’s level courses or retraining in a different major until they can obtain a suitable job offer.

The main risk for institutions actively considering outcome-based financing is that they might pin their hopes on a specific financing vehicle and then try to back into a strategy and supporting business plan. That would be letting the tail wag the dog. A much better way to serve the long-term financial and academic interests of schools and their students is for schools to start by aligning on a strategic goal and target segment, then define an appropriate business model, and then identify financing mechanisms that fit the goal and align with the business model.

Schools must also carefully manage institutional risk. An outcome-aligned program that is perceived, rightly or not, to be unfair—for instance, because the school or a private-sector funding partner is generating outsized financial returns off students’ payments, or because students who are already at risk are taking on more, albeit outcome-aligned, debt—can hurt a school’s brand positioning.

Use Market Research and Testing to Assess Loan Appeal and Uptake Among Target Student Segments

Universities should not assume that they know how various segments of students will respond to alternative financing offers. Moreover, it is unrealistic for a university to expect universal uptake in response to a single outcome-aligned financing option offered to the entire student body. In reality, different student segments are drawn to different financing vehicles, and schools often get the best results by deploying several outcome-aligned financing options, each targeting different student segments.

Schools should use market research to determine which groups of students are most likely to respond favorably to specific types of outcome-based financing. Two steps are especially useful:

- Conduct surveys and focus groups. These tools will give schools the quantitative and qualitative data they need to identify which financing options appeal to which segments. The data can also help them gauge the size of each target market and determine how to position each financing offer to maximize uptake. Researchers at Vanderbilt University, for instance, have found that the way student financing options are framed and named can make a big difference in their acceptance rates.

- Carry out pilot programs. Of course, student behavior in the real world is unlikely to correspond exactly to attitudes expressed in surveys, focus groups, and interviews, especially in response to a new financing program that students find unfamiliar. In addition to market research, therefore, schools should undertake small pilot programs to test which types of outcome-based financing get the greatest uptake, and then refine those programs as needed to hit target metrics.

For example, schools can use A/B tests to compare enrollment yields for students who receive traditional financial aid versus those offered outcome-aligned funding at equivalent net cost to the school (as measured by cash out minus cash in). Schools can use iterative and agile processes to repeat A/B tests with various messages in multiple market segments. A/B tests can yield surprising results, as in the case of a $20,000 income-sharing agreement versus a $10,000 financial aid award. Even if the ISA has only a 50% repayment rate (because of poor employment outcomes, say, or a lack of regulatory oversight that inhibits collection efforts), the expected value of the ISA is the same as that of the half-as-large financial aid award. Experience with A/B testing on outcome-aligned financing shows that prospective student yields are generally higher with the ISA than with only a financial aid award, perhaps because students may base their enrollment decision on how much a school seems to want them, which they associate with the nominal size of the financing offer rather than with the financing vehicle.

Identify Leading Measures to Track

Acquiring sufficient market data to determine outcomes and the cost to fully finance a program can take at least a decade. That’s because ascertaining full results entails allowing time for students to matriculate, graduate, be employed or attend graduate school for several years, and get on a career trajectory. In the interim, it’s important to track such essential data as the impact on enrollment decisions; choice of first employer, graduate school, or career pathway; and details of employment such as earnings and retention.

Make Sure the Business Models Can Hold Up

Schools can’t help students find better ways to finance their education unless they themselves are on a sound financial footing. Financial modeling can help colleges and universities calculate the potential payout from any outcome-aligned student financing programs. Such modeling should cover two key points:

- Decide who’s eligible. For example, if a university wishes to offer outcome-aligned options to graduating seniors, it must decide whether to open the program to all or restrict it to certain segments of the student body. If any student can opt in to the program, there’s a chance that only students with the greatest downside risk (for instance, majors with the lowest expected earnings) will sign up, requiring the university to pay out for that entire cohort of students. Funding for incoming first-year students is especially challenging. Predicting early career outcomes is more difficult for students at the start of their academic career since, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, about 80% of college students change their major at least once.

- Consider different economic conditions. Financing that includes a university payout naturally looks compelling when job markets are robust. But in a recession, such an approach could lead to a significant financial shortfall, depending on how the outcome-aligned financing is structured. Of course, there is nothing inherently wrong with committing to significant cash outlays, assuming that the program delivers on its strategic goals. But if higher-ed finance departments are to avoid unwelcome surprises, they need to be able to anticipate the impact of such programs.

The many variables involved in alternative financing underscore the importance of having strong modeling capabilities and of regularly revisiting projection models to revise assumptions in response to new conditions and data from prior student cohorts. For instance, a school might expect an outcome-aligned financing program to have a big impact on its overall finances—but if student uptake turns out to be low, the school will have to revise its assumptions and either adapt its goals or find ways to make the program more appealing to its target markets.

Design and Stick to Clear Implementation Plans

The mechanisms that schools use to deploy alternative financing options can powerfully affect the programs’ impact and success. For example, some LRAPs require alumni to repay the loan before seeking reimbursement. Such LRAPs come with plenty of paperwork and the perceived risk that the reimbursement may not go through.

Missteps in implementation can doom even the most well-intended and soundly structured outcome-aligned program. If initial rollouts are premature, or if early cohorts have an uneven experience, the university may struggle to recover its momentum. Similarly, word of mouth travels fast among students, and frustrations with how an outcome-aligned program is administered can depress enrollment yield.

Schools can improve the success rates of their outcome-aligned programs by putting real effort into the design of their implementation plans. The plans should include detailed timelines and should spell out responsibilities, dependencies, and milestones. Schools should then monitor leading indicator metrics to ensure that targets are being met. Programs must have sufficient capacity to enable robust, repeatable execution. Institutions must provide thorough training to financial aid officers and other frontline staff to ensure that they understand the specifics of any alternative financing mechanisms and can explain the new programs in detail. Any confusion or hesitation on the part of the staff can result in fewer students signing up for these programs.

Get Ready to Innovate

The current model of runaway financial aid—in which either the school or the student bears the risk in the form of escalating loans—is not working. To grow enrollments and demonstrate ROI, institutions must deliver the right quality of talent in the right quantity to meet workforce needs. This cannot be a one-sided process, however. Instead, students and institutions must share responsibility, often with the help of employers and government. And that requires innovation.

The field of student financing is alive with early experimentation, yet it demands much more innovation. Recent experience with seeding and testing alternative financing structures suggests that schools can achieve substantial wins by experimenting with various student financing vehicles and ways to market those programs to students until they arrive at a mix that appeals to a broad cross-section of students.

By deploying a range of outcome-aligned financing programs, schools gain more flexibility to adapt their approach as conditions change. For example, when the job market is tight, both schools and employers may be willing to assume more risk in their alternative financing approaches; but when demand is weaker, students should be willing to accept more risk. By maintaining an agile mindset and keeping tabs on market conditions, schools can adapt their outcome-aligned financing programs to find the best balance between minimizing risk and achieving strategic goals. Both testing early models and scaling them are critical to the success of innovation.

Maintaining an agile stance in which a school isn’t betting the house on a single financing program is also important for regulatory reasons, as the federal government seeks to clarify the nature of new vehicles. For instance, in the past year, the U.S. government has argued that ISAs are private loans and should be regulated as such, and it has asserted that investors in for-profit institutions that receive federal loans must financially back students in the event of institutional collapse or fraud.

Expanding and Innovating on Proven Models

Encouraging innovative approaches to student financing and remaining open to tried-and-true methods are not mutually exclusive endeavors. Specifically, the employer-backed loan forgiveness model has been in use for many decades by employers that, in partnership with top higher-ed institutions, pay for employees to pursue an MBA or other upper-level degree. So the practice and the payment structures are well established.

Employers are partnering with schools in such high-demand fields as nursing and accounting—both of which require passing accreditation exams—to adopt employer-backed loan models. Access to these vehicles is expanding, and funding levels for them are increasing, thanks to their initial success and to the persistent talent gap that they help address. Established vehicles have some distinct advantages. Loan forgiveness, for instance, is fairly simple for admissions and financial aid offices to explain. It appropriately puts the onus on the student to complete the program and stay employed for an agreed-upon period (typically two to four years). Meanwhile, the student retains the option during the program to choose another employer. This flexibility is important to students, who find being locked in with an employer from the start unappealing. Loan forgiveness also reinforces ideas of creative exploration and self-reflection that higher-ed institutions seek to foster. And it offers a ready source of capital—namely, employers—more than 80% of which would welcome greater involvement by higher ed in job preparation, according to a 2020 BCG-Google survey.

For higher-ed institutions, a combination of market demand, outside sources of capital (in this case, employers), and simple-to-explain vehicles with a successful track record can help an outcome-aligned student financing program gain significant uptake and become sustainable.

Ultimately, an institution’s decision about which vehicles to offer depends on its goal, its target student segment, and its ability to generate capital to fund the program. We hope to see schools pursue thoughtful experimentation with rigorous measurement of results to find out what truly works for whom.