A mere four years after its founding, Airbnb was operating in 89 countries and had just become a Silicon Valley unicorn. Then came a raft of property-trashing incidents. In response, the company radically upped its host-property guarantee to $1 million. Since then, with every new form of mishap, transgression, or breach, whether by hosts or guests, Airbnb has steadily amended or expanded its safeguards (including age restrictions, identity checks, and reviews) and its ground rules (which are designed to ensure fair play and accountability and offer recourse for repeat offenders).

Consider the converse: In Uber’s early days, to fend off mounting competition from Lyft and to grow the business faster, the company saw the need to expand capacity and lower prices. To attract more drivers, the company waived the commercial driver’s license requirement. While controversial at the time, relaxing this safeguard transformed the shape of urban mobility.

Safeguards are meant to protect either or both sides of a transaction or interaction in an online ecosystem and reduce negative outcomes. Too few can hinder an ecosystem’s growth. Yet too many can be time consuming and costly to maintain and potentially intrusive, stifling relationships and other positive outcomes that spring from a free-market exchange.

So how do companies know when their safeguards are too onerous? How many are too many? Conversely, how can companies tell when there are not enough? In designing safeguards, ecosystem orchestrators must find a sweet spot. Because trust is at the heart of digital interactions and ecosystem success, safeguards should be the concern not only of operations but also of orchestrators and participants.

What Exactly Are Safeguards?

Safeguards refer to the precautionary mechanisms that an ecosystem relies on to mandate or promote desirable behavior and engender trust among its participants. There are many types of safeguards—including policies, practices, and tools—and multiple types can be used to address the same concern. Safeguards may include hardware, software, and human-enabled mechanisms. For example:

- Escrow and blockchain mechanisms that aim to foster transparency in a transaction

- Identity verification tools, such as passwords, biometrics, and multifactor authentication

- Data controls that allow users to monitor or get information about counterparties and that protect users‘ privacy

- Digital reputation tools—including ratings, reviews, and awards—that serve as signals about sellers’ behavior and integrity

- Constraints, such as policies, sanctions, and contracts

Safeguards do their work at many junctures in the user journey. Depending on their type, they get baked into operating models, the user experience, marketing practices, and software and payment systems, for example.

Advanced digital technologies have opened the door to new types of safeguards

and their unprecedented usage, which will only continue to grow. AI-driven algorithms, for example, are frequently used to identify and block fraudulent transactions. While the scalability of these technologies makes them powerful tools, ecosystem leaders need to actively gauge their true impact (individually and in aggregate) in amplifying, neutralizing, or diminishing the desired behaviors.

Why Are Safeguards Mission Critical?

Safeguards are ultimately about generating trust, and virtually every ecosystem—whether it is Alibaba or Etsy, Lyft or DoorDash, Google Play Store or Apple’s App Store, or Airbnb or TrustedHousesitters—depends critically on trust. With the rise of ecosystems, and as digital interactions increasingly replace interpersonal dealings, trust has become a vital currency for economic success—the element that greases the wheels of an ecosystem, allowing it to scale. In fact, our research shows that among successful ecosystems, 86% had actively embedded trust mechanisms (of which safeguards are the lion’s share) into their ecosystems and practices. An orchestrator cannot build an ecosystem and hope that trust will emerge spontaneously among strangers. An orchestrator has to design for trust.

An ecosystem orchestrator cannot hope that trust will emerge spontaneously. It has to design for trust.

Importantly, safeguards enable actions and engagement by providing reassurances that participants can trust the ecosystem even if they lack experience with (and haven’t developed trust organically with) the counterparty. Safeguards help align expectations about processes and outcomes, thus reducing the uncertainty about the counterparty’s behavior. They also provide economic incentives for a partner to behave in a trustworthy fashion. In this way, safeguards foster trust in the overall ecosystem—what we deem as systemic trust—making trust between counterparties less crucial. Yet well-designed safeguards can also work to foster relational trust—trust between two parties—not just systemic trust.

Are More Safeguards Always Better?

An under-reliance on safeguards raises the risk of undesirable behavior, negative outcomes, and even friction. Friction is anything that makes participants wait or hesitate to act or that causes confusion or frustration. Uber Eats, for example, recently discovered that many restaurants were listing multiple brands on the platform with the same menu—brands coming from online (virtual) storefronts. Customers were thus seeing dozens of versions of the same menu on the app, which made searches annoying. Such friction can lead to churn or, worse, failure.

On the contrary, an excess of safeguards can stifle the interactions that make trust flourish organically among participants and that spark innovation, creativity, and other often unexpected benefits. In addition, too many safeguards almost always come at a cost. Apart from the direct costs involved in implementation and enforcement, an excess of safeguards can make the user experience more frustrating, bureaucratic, and generally less enjoyable. An overabundance of safeguards can also make participants suspicious; they wonder why there are so many constraints. That reaction undermines the very purpose of safeguards. As a result, participants may become circumspect, less loyal, and more likely to go elsewhere.

The trick for ecosystem orchestrators is to strike the right balance between control and autonomy. The right balance depends on several factors, including the ecosystem’s purpose, participants’ characteristics, the nature of the goods or services being bought and sold, and how high the stakes are. For instance, a marketplace offering handcrafted artistic goods may reasonably require each seller to provide a variety of unique high-quality product images, whereas an e-retailer selling commoditized goods may allow generic images. A platform for long-term housing rentals may require a credit score check on prospective tenants, while such a safeguard wouldn’t be necessary for a one that rents vacation homes short term.

The trick for orchestrators is to strike the right balance between control and autonomy.

Whether to err on the side of having more or fewer safeguards can be one of an orchestrator’s most challenging and consequential design decisions. To illustrate, an orchestrator of a peer-to-peer marketplace might consider asking these questions:

- Should sellers be able to sell whatever they want? Should the company verify that the sellers own the products they are selling or document sellers‘ credentials?

- Should sellers be able to set their own terms for pricing? Should buyers be allowed to negotiate the price?

- Should sellers be able to take as long as they want to deliver purchased items?

- Should buyers have full access to sellers’ contact information?

- What are the return limitations for buyers?

- Should the company release payment when a seller indicates that an item has been shipped or when the buyer acknowledges receipt?

These decisions don’t apply to just retail ecosystems; every ecosystem orchestrator, whether managing relationships between hosts and guests, artists and patrons, or any other set of counterparties, has hundreds of decisions to make along these lines.

What Factors Should Orchestrators Consider?

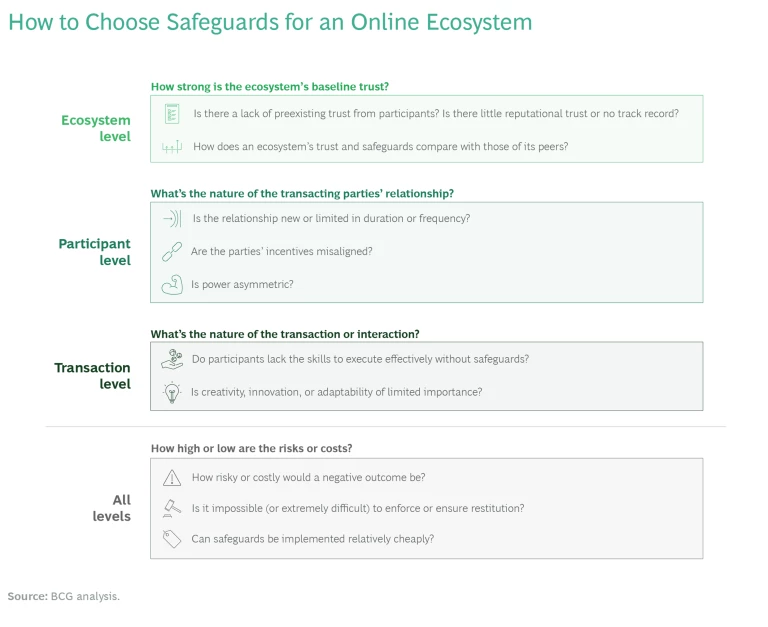

When deciding which safeguards an ecosystem needs and what constitutes the optimal mix, an orchestrator should consider a number of parameters. (See the exhibit.)

Here are a few of the more important ones.

The Power Asymmetry Between a Seller and Buyer. A classic example of a safeguard to address asymmetric power is the use of escrow: a marketplace orchestrator withholds payment to sellers (especially new ones) until they submit proof of shipment. Another is offering a guarantee to buyers, such as a 30-day free-return policy, or imposing a penalty on sellers who don’t adhere to the ecosystem’s policies and practices. In addition to transaction-oriented power asymmetry, there is the innate relationship-oriented type. An orchestrator needs to serve as a regulator for both kinds of power asymmetry, ensuring that the more powerful actors don’t abuse their natural advantage.

An orchestrator needs to ensure that the more powerful actors don’t abuse their natural advantage.

In contrast, when power dynamics are less one-sided, fewer safeguards are typically needed and may be counterproductive. For Uber and Lyft, for example, general contracting checks (that determine if a driver has a good driving record, for example) and customer reviews do a fairly good job of ensuring appropriate behavior. The auction site uShip, which connects those seeking discounted shipping services with carriers (chiefly truckers wanting to avoid deadheading), provides basic tools (including listings, policies, a messaging center, and profiles) along with optional tools (a tracking app, for example) and suggestions for both parties (such as creating a written agreement using their template).

The Sophistication or Skill Level of Participants. More safeguards may be warranted for ecosystems that eliminate intermediaries, that have more technically or legally complicated transactions, and whose users have relatively little experience. Consider ecosystems where real estate is sold by owners. The risk for participants isn’t necessarily about encountering unscrupulous counterparties. It’s more about both parties—nonprofessionals—making mistakes in a deal as complex as a house purchase. Some do-it-yourself real estate ecosystems contract with third parties to offer safeguards such as documentation reviews and process assistance. Platforms where participants buy and sell heavy equipment are another example of ecosystems that may need more safeguards, since such sales have traditionally involved brokers or distributors.

When most participants in an ecosystem have the necessary skills or knowledge to understand key aspects of a transaction, safeguards tend to be less critical. In fact, for participants with advanced skills, too many safeguards bureaucratize a process, adding unnecessary complications, not to mention increasing costs. Consider a commercial real estate platform designed for professionals. Too much red tape could cause deals to drag out, potentially causing one or both parties to lose an opportunity or possibly risking a change in transaction costs if interest rates or market prices fluctuate.

The Nature of the Transaction. When creativity is central to the ecosystem’s purpose, less may be more when it comes to safeguards. Patreon connects patrons and creators of all types, including visual artists, writers, videographers, and humorists. Rather than buy a specific product, users subscribe to receive content from creators. There are relatively few safeguards surrounding these offerings, allowing Patreon’s 250,000 creators the freedom to design their own packages of content and pricing tiers. Creative content is, after all, not a commodity, and even for a single creator, the time it takes to produce art—a sketch versus a series, or a song as opposed to a sonata—can vary greatly.

When creativity is central to the ecosystem’s purpose, less may be more when it comes to safeguards.

Art is one thing; technology is another. As an open-source operating system, Linux needs to encourage innovation. But because major institutions and businesses worldwide depend on the system, some safeguarding is in order. A hierarchy of code maintainers ensure integrity by evaluating input from contributing developers. This modest counterbalancing safeguard ensures that the platform allows for creativity and collaboration among the thousands of developers in its community.

The Cost of a Negative Outcome. When the stakes are relatively low, or a negative outcome is relatively easy to fix, there’s less of a need for stringent safeguards. A food delivery app, for example, may guarantee only the price or the speed of delivery, not the quality of meals from its restaurant purveyors. And to exercise that guarantee, a user must take the time to submit a complaint and await the company’s reply, an effort that many would deem too great to recoup a modest difference in meal cost or be compensated for a longer wait. A platform selling vintage knickknacks or handmade costume jewelry may not require an upfront proof of provenance; the ability to return for a refund is all that a disappointed customer would expect with such goods.

But with a high-stakes interaction or transaction, more (or more stringent) safeguards tend to be better. A marketplace specializing in antique estate jewelry or rare manuscripts would likely require documented expert authentication of each item to protect buyers. HopSkipDrive, a ride service designed to transport unescorted kids, provides multifactor authentication upon pickup to ensure that kids and drivers find each other safely. In addition, a real-time tracker allows parents to trace the location of the car transporting their child while it is in transit. Background checks for drivers are considerably more rigorous than for other ride-hailing services. Despite the fact that the checks may scare off some potential drivers, thus hindering the ecosystem’s growth, such robust safeguards are vital for engendering the trust of customers under such circumstances.

Buying a car online at eBay is a far bigger gamble than buying a steering wheel cover or replacement headlights. EBay Motors and most other online auto marketplaces offer free Carfax reports on each vehicle’s history. EBay’s vehicle protection program covers buyers up to $100,000 and protects against such risks as not receiving the title (or the car itself), an undisclosed lien, and unknowingly purchasing a stolen vehicle.

The Cost-Benefit Tradeoff. Whether it’s dispute-resolution mechanisms or authenticity-verification tools, implementing and maintaining safeguards may not be cheap. Ecosystems often operate on slim unit economics (often earned as a percentage of each transaction’s value), so it is usually unfeasible to support extensive safeguards. Orchestrators, therefore, need to weigh the cost-benefit tradeoffs.

It’s also impracticable for a massive online marketplace, such as Amazon or Alibaba, to inspect vendors’ wares before they are shipped to customers. The user rating system substitutes reasonably well (albeit not perfectly); it’s a marginal cost for an orchestrator, yet offers an easy and valuable solution for buyers and sellers. Still, there are many cases in which the stakes are high and the benefits justify the costs. Uber and Lyft, for example, need to ensure that their drivers are licensed and insured; the failure to do so can result in significant fines, liability, regulatory action, and bad press.

Implementing safeguards is not a one-and-done exercise. It is imperative to continuously monitor and adapt them.

Competition and Change Make Adapting Safeguards Essential

Implementing safeguards is not a one-and-done exercise. Changes in an industry, a user base, technology, or an ecosystem’s business model or strategy make it imperative to continuously monitor and adapt safeguards. But change isn’t always gradual. A disruptive innovation or major breach that harms participants and the ecosystem itself may trigger the need to modify safeguards drastically.

Many of the safeguard adjustments that Elon Musk has instituted at Twitter since buying the company—loosening restrictions in some areas, clamping down in others—illustrate the delicate balancing act that managing safeguards can be, particularly in social media.

Competitive pressures may also need to influence safeguard decisions, especially in an increasingly winner take most (if not all) world. Uber relaxed its initial requirement of a commercial driver’s license to match Lyft’s less stringent one. Safeguards can also be a means of strategic differentiation; Google, for example, opted for fewer safeguards for its app developer ecosystem than did Apple.

Implementing and Adjusting Safeguards

How does an ecosystem orchestrator apply parameters in practice to achieve the right balance between control and freedom? First, consider the ecosystem as a whole. Identify which two or three parameters appear to best define the need for safeguards—or their downside. In addition to the parameters we’ve described already, others include the ecosystem’s preexisting reputation and track record and the typical nature or maturity of participant relationships.

Then, break down the ecosystem into value streams of participants’ experiences to pinpoint where more or fewer safeguards would be useful. For drivers of a ride service, for example, identify the various stages of their experience, including signing up, passing a background check, onboarding, setting up a payment method, receiving reviews, and resolving problems.

What happens when parameters conflict? Say the need for creativity (and thus, fewer safeguards) is high, but the cost of a negative outcome is also high. In that case, dig down to a more granular level to isolate the value stream activity with a high need for creativity and the activity with a high level of criticality. If they can’t be separated, prioritize using safeguards in a way that benefits the critical aspects of the activity without hindering its creative aspects.

After establishing and prioritizing the trust issues, identify the appropriate safeguard or safeguards that are needed. Choose metrics to gauge safeguard balance—both the overall balance and that of high-priority elements. Then, monitor, test, and iterate as needed. Due diligence will be an ongoing exercise of pulling back and pushing forward to maintain that delicate balance of freedom and control.

With the right mix and the right number, safeguards are a key to an ecosystem’s health and growth. They are not merely elements of the operating model; they are also central elements of the ecosystem’s value proposition and its competitive advantage. So, finding the sweet spot between control and autonomy, risk and reward, is crucial. It requires constant vigilance and tweaking, as the competitive landscape, technology, and user expectations evolve—or get disrupted. In nature, adaptation is everything. So it is with digital ecosystems and their safeguards.