Climate change is an urgent health crisis. As the World Health Organization (WHO) notes, it presents a fundamental threat to health. The consequences are already being felt today. The increasingly severe and frequent climate-related events around the world, from rising temperatures to floods, have significant direct and indirect impacts on human health. ( See “Climate and Health by the Numbers.”)

Climate and Health by Numbers

This will only get worse. BCG analysis in Southeast Asia found that certain regions could face over 100% increase in dengue and leptospirosis incidence in the 2030s due to extreme rainfall. We also expect that an additional 180 million people in Africa and Asia will be at risk of malaria by 2030 under a medium emissions scenario.² And by 2040, approximately 25% of children will live in areas of extremely high-water stress.³ Given the extreme likelihood of negative impacts of climate change on infectious diseases like malaria and dengue, cardiovascular diseases, heat exposure, nutritional deficiencies, and mental health, there’s an urgent need to prepare and respond to these CSHRs now.⁴

¹The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change, November 5, 2023.

²Guéladio Cissé et al., “Chapter 7: Health, Wellbeing and the Changing Structure of Communities” in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, IPCC Sixth Assessment Report.

³UNICEF website, as of August 2, 2023.

⁴Guéladio Cissé et al., “Chapter 7: Health, Wellbeing and the Changing Structure of Communities” in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, IPCC Sixth Assessment Report.

BCG conducted a study of more than 70 organizations to understand how key stakeholders are approaching the climate-health challenge.

At the first ever Health Day at COP28 , 123 countries signed the Declaration on Climate and Health. Although it was a great step in the right direction, it is not enough. With the health care ecosystem both contributing to and impacted by climate change, there’s a lot of work to do on mitigation and adaptation. Careful coordination is needed across funding and implementation to ensure that stakeholders focus where it is most impactful.

BCG conducted a study of more than 70 organizations—including philanthropies, multilateral development banks (MDBs), government agencies, nongovernmental organizations, private sector actors, and others—to understand how key stakeholders are approaching this complex challenge. (See “

About Our Research.

”) We found that:

- The ability to address the intersection of climate and health is hindered by the complexity of the climate-health relationship, which makes it difficult to prioritize action, as well as the limited tools, capabilities, and resources available to stakeholders. Climate and health players lack a common way to talk about and frame the issues and actions, as well as the evidence-base needed to inform their actions.

- Current efforts are often fragmented and nascent, and there is still poor transparency on what other organizations are doing.

Our findings point to the value of developing a strong evidence base on the ways that climate and health intersect and building transparency on what different funders, implementers, and policymakers are doing to address it. This will enable organizations to prioritize activities based on the role they want (and are best positioned) to play, current levels of funding and attention, and the future health burden attributable to climate. It will also allow organizations to better collaborate with each other and to mobilize around cost-effective, impactful solutions.

We hope that unlocking a coordinated and prioritized approach, enabled by evidence and transparency, will accelerate progress on climate and health . Right now is the time to build on the momentum and commitments generated at COP28.

Key Obstacles for Stakeholders

Our research identified three challenges to taking action on climate and health.

The relationship between climate and health is complex. Climates broad impacts range from injury and mortality from extreme weather events to escalating infectious diseases, malnutrition, and mental health impacts to worsening health outcomes due to reduced health service delivery (such as when a clinic is flooded). Then there are also health’s impacts on the climate. This complexity and breadth were reflected in the wide-ranging topics discussed at COP.

However, the specific risks, levels of vulnerability, and magnitude of impact differ across locations and demographics. For example, there are more than 200 human diseases that can be aggravated by climate change and more than 1,000 different pathways of transmission.

Our research identified three challenges to taking action on climate and health.

Decision makers lack the tools and data they need. Despite the growing body of evidence linking climate and health, better data—and stronger evidence—is still needed to enable the setting of priorities. The most recent assessment of projected climate-related annual deaths by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) noted a lack of available literature for some diseases and most mental illnesses.

Capital and resources remain limited. Despite encouraging recent commitments from philanthropies, countries and MDBs and collaboration on funding (e.g., a new co-investment facility from GCF, UNDP, and WHO; a new climate and health initiative by ADB), the total amount of funding is still likely insufficient. While the COP28 press briefing referenced over $1 billion of funding for climate and health, much of this is a commitment to add a climate-lens to existing health funding vs incremental additional funding or is in early stages, without clear priorities for near-term investments.

What Organizations Are Doing

Out of the global health funders we examined, foundations (often by applying climate or health lens to their existing portfolios) and multilateral development banks (through both specific climate and health strategies and cross-sectoral funding) are helping pave the way on climate and health.

Many governments don’t have clearly defined or published official development assistance strategies on climate and health, but they still recognize the overlap and intersection between the topics and have committed funding to the topic. For example, 123 countries signed a Declaration on Climate and Health at COP28, committing to incorporate health targets in their national climate plans and increase international collaboration. In other notable developments, the UK has committed £18 million to support partner countries to assess vulnerability, identify priority actions, and support planning in climate and health.

Governments are also introducing domestic policies on climate and health. Notably, 91% of nationally determined contributions to the Paris Agreement now include health considerations.

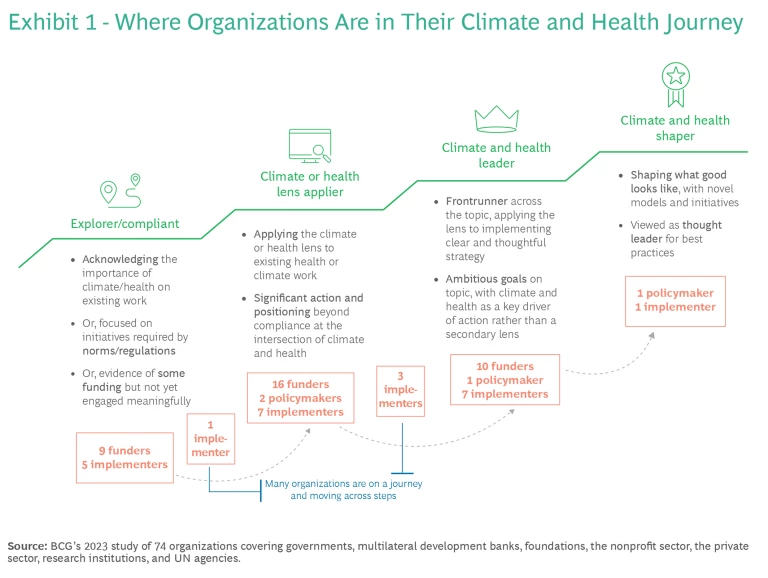

However, despite several players clarifying their ambition and releasing strategies in the run up to COP, most of the players we assessed are still early in their journeys—exploring what a climate and health offering looks like and where their action is most needed—and many are applying a climate or health lens to their existing priorities rather than leading or shaping the field. (See Exhibit 1.) Few have clear, discrete, and ambitious enough strategies. However, 20 organizations, while still figuring things out, stood out in their ambition and efforts to drive action in the ecosystem.

Four key observations from our study:

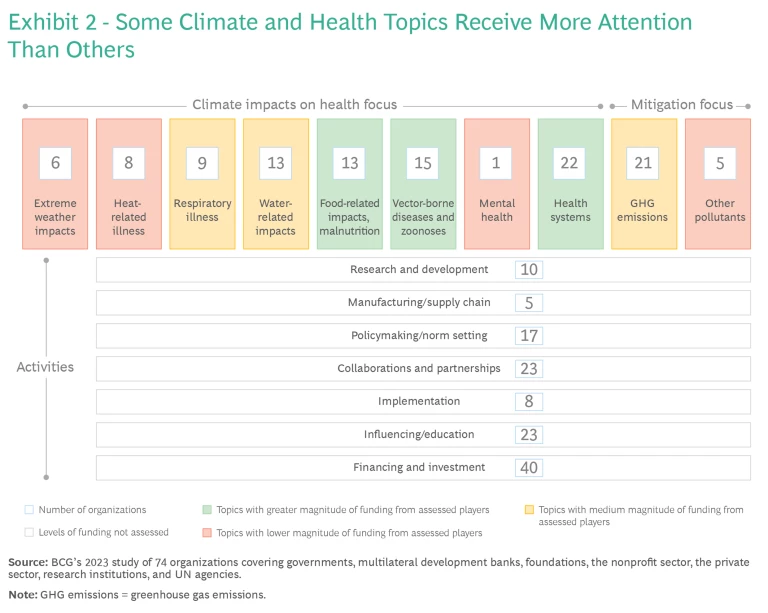

- Foundations, policymakers, and other implementers are mapping out clear topic spaces that they play in. These spaces are aligned to existing portfolios on air pollution or food and agriculture, for example. Among the organizations we assessed, we found that most topics are covered, but there is less focus on extreme weather, mental health, and other pollutants. (See Exhibit 2.)

- Many of the players we examined are funding or investing in climate and health. By contrast, fewer of those we evaluated are implementing solutions, working to decarbonize health supply chains or conducting research and development. (The latter of which partly reflects that our study included few academic institutions.)

- Action is fragmented, with few mature and investable climate-informed concepts to rally around and is often not linked to clear or data-informed prioritization. This is particularly the case for adaptation topics, where the best course of action and best value for the money remains unclear to many due to a nascent evidence-base. These players are also supporting efforts that will benefit the climate and health nexus, even if not directly targeted to it, including health systems strengthening, development of digital health care systems, and disaster relief.

- Adjacent actors that are not the typical global health players are helping solve for health impacts, even if that’s not their primary focus. This includes organizations working on urban redesign, green infrastructure, clean-cooling initiatives, electric vehicles, green energy, and adaptation and resilience. There is potential for stronger collaboration and funding across sectors on climate and health topics, and a strong advocacy agenda is required to centralize health impacts in planning and implementation.

Accelerating Progress

Building on our findings and learnings from other global efforts, we have identified three key actions that climate and health players can take to help accelerate action.

Coordinate and develop the evidence base. Decision makers need a stronger base of evidence to inform the setting of priorities. They need to understand where, and to what extent, climate change will affect human health, as well as the potential impact of various interventions and economic consequences. WHO and IPCC assessed the future burden of climate-sensitive health risks (CSHRs) in 2014, finding heat and undernutrition of greatest concern until 2050—but this assessment is almost a decade old and limited to certain impacts. While evidence is growing, there is still a pressing need to coordinate and develop the evidence base that will allow organizations to assess where the highest need is.

There are three key actions that climate and health players can take to help accelerate action.

Double down on prioritization: We can act on the known risks now. Once we understand the relationships, impact, and economic consequences, we will be able to re-evaluate and prioritize efforts and ensure that our action is balanced and appropriate to burden, across and within geographies and topics. A better understanding will help us assess whether and where our limited resources are best spent (e.g., on mitigation vs adaptation efforts, specific impacts, etc.), and what sort of action is needed. Some key questions to ask:

- Should we continued to do what works, and scale it? Do current research, solutions, and geographic focuses remain the most appropriate course, and require similar or increased resources? This might be the case for diseases that have low chance of being exacerbated by climate-related events or where the incidence rate may increase but the approach to addressing the disease is unlikely to change.

- Should we adapt existing programs? Are small changes required within existing mechanisms? This might be the case for vector-borne diseases that will see changes and expansion in endemicity ranges and transmission seasons, thus necessitating changes in the geographical scope of interventions.

- Do we need to undertake strategic change? Are current programs and mechanisms unable to address the most significant impacts, either globally or in a specific location? This may be a case where specific health areas or enablers are critical to address but not covered by current portfolios, or where the impact of climate change is transformational and therefore we need a different approach to addressing the impact.

Given the breadth of the climate and health nexus, it will be important that stakeholders mobilize around a prioritized, data-driven shared agenda to ensure maximum impact.

Build transparency to unlock collaboration. With several strategies published in the run-up to COP, organizations are starting to build transparency. However, with new players entering the field and deciding where to play and as more nascent strategies are translated into specific near-term actions or priorities, there’s a long way to go. Global health players will benefit from a greater understanding of what others are doing, so that all can more effectively target their contributions, secure funding, and work with each other to mobilize around a shared, high-impact agenda, otherwise we risk unhelpful fragmentation. Uniting around a common terminology and framework that help understand the climate and health landscape and priorities will be important in this.

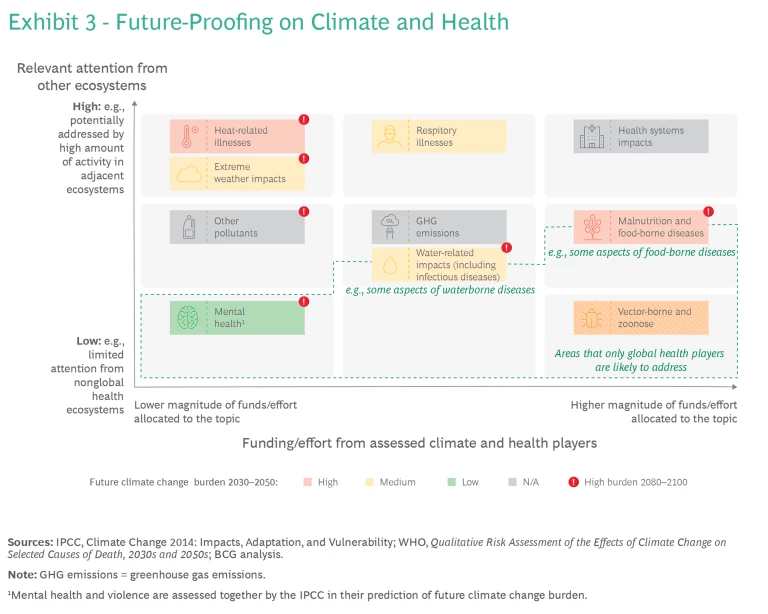

The prioritization discussed above needs to be actor specific. Different types of players will be positioned to address different impacts, and in different ways—be it by influencing, funding, or implementing solutions. For example, we identified significant action in adjacent fields that may address some CSHRs. For these CSHRs, global health influencers can deliver great value by targeting advocacy efforts on these ecosystems, and global health researchers can advance thinking on the health-specific impacts. On the other hand, global health funders and implementers may need to play a more direct role in tackling certain vector-borne diseases and zoonoses and mental health impacts that will be unlikely to be addressed by activity in other fields. (See Exhibit 3.)

Organizations are increasingly acting on or interested in climate and health, and COP28 has helped deliver greater momentum. However, climate and health is still a relatively nascent and fragmented field, with limited funding, tools, and capabilities. To effectively mobilize around high-impact solutions, stakeholders should work together to build a stronger evidence base with respect to future burden, impact, and the effectiveness of solutions and compare this to current levels of activity and funding. This will allow organizations to establish where they should prioritize their actions. Crucially, without these actions, there is a risk that organizations greenwash health or don’t focus on the most urgent impacts or solutions with the highest return on investments—a waste the world cannot afford given limited resources.

The growing interest in tackling the intersection climate and health is encouraging. We hope that coordination of research, a stronger evidence base, and building transparency within the climate and health ecosystem will allow a more targeted and prioritized response—accelerating action that can save millions of lives.