The Asia-Pacific (APAC) region offers huge potential for renewables developers, investors, and operators. But its size and complexity mean that navigating the region’s renewables markets is far from straightforward. Because opportunities and challenges vary widely from one market to another, players must adopt a granular, de-averaging approach.

Despite the region’s diversity, we find that five factors are still essential across all APAC markets. Renewables players need to have a strong strategic focus, local partnerships, a broad selection of financing options, proactive

supply chain management

, and offtake expertise. Players must build these factors into their plans in order to succeed.

The Promise of APAC Renewables

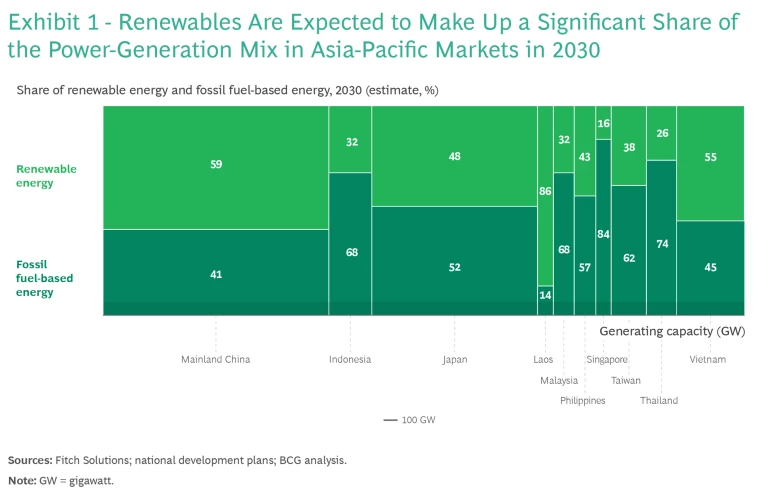

Renewable-energy development in the APAC region is growing strongly—although from a low base. Installed generating capacity is expanding at an average compound annual growth rate of 9%.

Achieving this degree of renewables penetration will involve significant investment. The International Energy Agency’s Announced Pledges Scenario, which was updated in August 2023, anticipates that APAC renewables investments made from 2022 through 2030 will hit $286 billion.

Moreover, at the recent 28th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 28), nations made commitments to triple global renewable capacity by 2030. The fulfillment of these pledges could mean that renewable energy accounts for a bigger share of the power-generation mix within the region—and that APAC even exceeds our expectations of about 2 terawatts of installed generating capacity by the end of the decade.

Multiple forces are driving the boom in APAC renewables development:

- Lower Costs. The cost of producing energy from renewable sources has fallen steadily in recent decades, making it far more competitive with fossil fuel-based power generation in the region. Solar power (excluding battery costs) and onshore wind power are at or close to price parity with fossil fuels in large markets such as mainland China and Japan. We expect solar and wind power to achieve price parity across all APAC markets in the 2030s.

- National Climate Commitments. Since signing the Paris Agreement, most APAC economies have set ambitious goals for significantly reducing emissions by 2030 and achieving net zero or carbon neutrality by 2050. These commitments provide greater certainty about the long-term growth in demand for renewable energy as a key decarbonization lever.

- Private-Sector Decarbonization. The APAC region is a global manufacturing hub, one that is expanding as many multinational corporations relocate their supply chains in the region. At the same time, companies with operations in the region are adopting decarbonization goals in line with global standards, such as those developed by the Science Based Targets initiative. This shift toward decarbonization is increasing renewable-energy demand among companies and creating new offtake arrangements.

- Localized Renewables Manufacturing. Selling renewable-energy equipment that is manufactured in mainland China to the European Union and the US is subject to restrictions. As a result, the development of renewables manufacturing elsewhere in the APAC region has accelerated. Markets such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Taiwan are focused on building export industries to produce renewables products, including solar photovoltaic (PV) panels and low-carbon hydrogen. These industries provide a convenient, nearby source of equipment supply and expertise for developers in the region.

- Electricity System Reforms. APAC markets, including mainland China, Malaysia, and Taiwan, have implemented significant reforms to their electricity systems. These reforms provide renewable-energy developers with new ways to sell power, including directly to companies, replacing traditional offtake mechanisms such as feed-in tariffs (the price renewables developers are paid for selling power to the grid) and grid-reliant power purchase agreements (PPAs). The reforms encourage innovation and flexibility and boost market efficiencies, thereby creating a more supportive environment for renewables developers.

- Regional Power Trading. The growth in cross-border regional power trading is helping to encourage the development of renewable-energy projects. Recent initiatives include the expansion of a regional power grid serving members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). In addition, under a renewables pilot project, Singapore is importing up to 100 megawatts of hydropower from Laos via Malaysia and Thailand using existing grid infrastructure. Policymakers in the East ASEAN Growth Area (EAGA) are also developing a legal framework for renewable-energy certificates that promises to boost demand among companies in the EAGA.

How to Play in APAC Renewables

Given the expected growth trajectory of renewable-energy development in APAC, it’s not surprising that international investors want a piece of the action. Asian developers are also looking to win business across the region. All players, however, must consider the attractiveness of both the market and the project investment (including potential returns and ease of financing) before they commit sizable funds. We find that the best and biggest investment opportunities score highly on both.

Market-based factors differ significantly across the region. They include the quality of the grid infrastructure, local business practices, specific legal requirements, and cultural differences.

Similarly, factors influencing the investment attractiveness of capital-intensive renewables projects vary from market to market. Factors can include a higher risk of default among project participants (such as financial backers), execution challenges, and limited access to debt funding. Acquiring an equity stake in a project can be one way that new entrants overcome funding obstacles. However, several APAC markets, including mainland China, the Philippines, and Singapore, are dominated by established players, making it difficult for new investors and operators to compete. (See “Three Ways to Enter the APAC Renewables Markets.”)

Three Ways to Enter the APAC Renewables Markets

Build and Flip. Developers that use this model build a renewable-energy project and then sell a stake in it when the project reaches its commercial operation date (that is, when the project starts to generate power and earn revenues). This approach is favored by companies that want to free up capital to develop other projects or reduce the risks of full or partial ownership. In APAC, the build-and-flip model is commonly used for capital-intensive projects, such as offshore wind farms. Players often opportunistically sell an ownership stake—typically within five to eight years of the start of the project—if they can earn a premium on their investment. Buyers include utilities or developers seeking to enter local APAC markets.

Compared with other options, build-and-flip projects offer a better risk-return profile (internal rates of return are generally 5% to 10% higher than they are for the two other project types). However, these projects also come with higher transaction costs and more volatile profits than do own-and-operate projects, which benefit from stable cash flows owing to long-term contracts. To succeed with this approach, players need to be good at navigating the local business environment (especially land rights, regulations, and permitting), building strong relationships with local companies, and having robust engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) capabilities.

Own and Operate. Players that adopt this model develop a renewable-energy project but continue to run it after it’s operational. This model is favored by companies seeking both steady, long-term cash flows from power sales and rising valuation multiples (which are realized should the owner decide to exit) based on renewable energy’s growth potential, its scalability, and its increasing importance in achieving net zero.

The own-and-operate model requires players to commit more capital than other options do. This approach can also be more challenging because companies face exposure to power price volatility and merchant risks. To succeed as project owners and operators, players must invest not only in EPC capabilities but also in operations-based capabilities and risk management. Owners and operators often sell a minority stake later in a project’s lifetime as they balance control with greater financial flexibility.

Invest. This model is typically adopted by pension funds and asset managers seeking long-duration assets that offer reliable risk-adjusted returns and that benefit from strong environmental, social, and governance credentials. However, these financial players must accept the lowest risk-return profile of all three models, with internal rates of return of 2% to 3% below those enjoyed by owners and operators. As a result, access to capital with low interest rates is essential.

Although developers and investors must adapt to the business environment in each market, we’ve identified five factors that are important for success across APAC markets. (See Exhibit 2.)

Finding Your Focus. To avoid spreading themselves too thin, investors and developers should concentrate their efforts on a few markets and renewable-energy technologies. Selecting a technology that will provide a distinct competitive advantage is particularly important in APAC markets, where the risks of failure and sunk costs are high and, consequently, developers and investors are under pressure to achieve returns more quickly than in other regions.

Resource availability is often a key driver of market-specific renewables opportunities in APAC. For example, developers in Japan are prioritizing rooftop solar PV and offshore wind projects owing to the limited availability of land. Distributed solar power combined with microgrids is emerging as a growth area in the Philippines for electrifying the country’s many remote regions. And biomass-based projects are gaining popularity in southern Thailand because of the abundance of feedstock in that region and the prevalence of agricultural communities. (See “Renewables Opportunities Across the APAC Region.”)

Renewables Opportunities Across the APAC Region

Intermittent Renewables. Solar and wind power projects, whose output is dependent on weather conditions, offer some of the biggest and best investment opportunities in the APAC region owing to favorable regulations, technical ease of delivery, and few market-entry requirements. Project returns are typically from 8% to 10%. For developers and investors in large, utility-scale solar projects (those that feed power into the grid), Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines are among the most promising markets.

The Philippines is a particularly attractive destination for utility-scale solar investments. Utility-scale solar capacity is set to increase by 6 gigawatts by the 2030s. The country also offers a wide range of offtake options, and project returns (up to 12%) are higher than the average for the APAC region. While opportunities in ground-mounted solar panels are limited, floating solar farms are emerging as a significant market.

For distributed solar projects (which circumvent the transmission grid), mainland China, Japan, and Singapore are attractive investment destinations. Among wind energy projects, those that are onshore in mainland China and those that are offshore in Japan, the Philippines, and Taiwan offer potentially lucrative opportunities.

In mainland China, international players must clear a high bar to enter the utility-scale solar power market. Local solar developers sell energy to the grid under long-term regulated PPAs and have generating costs that are at least as low as developers that produce electricity from fossil fuels. However, there are opportunities for investors and developers in both utility-scale and distributed solar projects in provinces that suffer from a shortage of renewable-energy supply. These projects can also benefit from direct PPAs and market-based pricing.

Base Load Renewables. Opportunities exist in APAC for base load renewable-energy projects (which provide power throughout the day). These include hydropower projects in Laos and Malaysia and geothermal ones in Indonesia and the Philippines. However, more stringent regulations, high capital expenditure requirements, substantial execution and development risks, and long project cycles mean that these projects are less attractive than intermittent renewables projects, such as solar and wind.

In Indonesia, for example, geothermal developers must meet a 35% local content requirement. They also have to deal with long development cycles (approximately 15 years to commercial operation) and uncertain tariff negotiations with a single buyer: the local utility. These factors make geothermal a viable option primarily for players with highly specialized technical and financial capabilities.

Establishing Local Partnerships. Forging strong partnerships with local players can be essential for unlocking access to land, navigating the local business environment—even gaining the right to develop a renewable-energy project in the first place. Malaysia, for example, is a key destination in the APAC region for solar power investment, helped by the country’s strong commitment to net zero emissions, export potential to neighboring Singapore, and growing solar PV manufacturing industry. However, under local rules, Malaysian interests must own at least 51% of any company developing large-scale solar installations.

Thailand’s renewables market is also geared toward domestic developers, making it difficult for foreign players to secure land or finalize offtake agreements on their own. To succeed in this market, foreign payers typically form a joint venture with a local player or acquire an equity stake in a local company.

In Japan, partnering with local players that have established relationships and a strong reputation, such as one of the country’s manufacturing conglomerates, is essential for developing renewable-energy projects. Such partnerships can help foreign developers with two key requirements when bidding for offshore wind tenders: a detailed plan for stimulating the local Japanese economy and the formation of a fund that distributes part of the wind farm’s profits to the local community.

Broadening Financing Options. In some APAC markets, foreign developers are experiencing pressure over projects’ internal rates of return because greater competition is leading to lower power payments. This is the case in Thailand, where a fall in feed-in tariffs has created pressure on players to optimize the cost side of projects to cushion the impact of reduced returns.

Local renewables players are better placed to withstand these challenging conditions. Because of low-interest sustainable loans from local banks, local players are more cost competitive than foreign developers are. In mainland China and Indonesia, we’ve found that financing costs are an estimated 4% to 8% lower for local state-owned enterprises than they are for international developers.

The rise of blended finance and green funding from multilateral development banks is set to close the gap between local and foreign developers.

However, the rise of blended finance and green funding from multilateral development banks and nations—through initiatives such as the Asian Development Bank’s Energy Transition Mechanism and Just Energy Transition Partnerships—is set to close the gap between local and foreign developers. These initiatives encourage international private developers to participate in APAC renewables projects by lowering their cost of capital and reducing risks. The Asian Development Bank’s initiative is using blended finance to rehabilitate hydropower projects in the Philippines and fund Thai renewables projects that combine wind farms with energy storage.

Access to development bank financing and similar funding sources allows international developers and investors to enter more saturated markets. But they still need to alter their expectations and become comfortable with potentially lower returns. For example, Taiwan’s rooftop solar market is an attractive market for renewable-energy players because of its double-digit growth, robust offtake mechanisms, and strong demand for power from companies. However, Taiwan’s declining feed-in tariffs and rising construction costs mean that would-be developers need to both secure low-interest loans and be prepared to accept single-digit returns.

Navigating the Supply Chain. When entering new APAC markets, players often face onerous requirements involving local partnerships and local content. In Taiwan’s offshore wind sector, 60% of the components of wind farms must come from local suppliers, 26 key components have to be produced locally, and foreign companies must create partnerships with local players to build farms. Foreign developers face similar challenges in Indonesia and Malaysia, both of which also have local content rules; while in Japan, bidders for renewables projects must show that they have stable supply chains and can meet short delivery lead times—both of which favor local manufacturers.

Such requirements mean that players need to take a tailored approach if they are to win renewables contract auctions. That’s because ensuring there is sufficient local content impacts not only project cost structures but also bidding strategies and supply chain management. In these situations, players should consider integrating companies in the upstream value chain—which in the case of solar-panel production includes suppliers of silicon, silicon crystals, and silicon wafers—more closely with their own operations through partnerships. This can result in cost efficiencies, enabling developers to both meet local requirements and maintain the financial viability of their bids. However, value chain integration involves a deep understanding of the local market, including the capabilities and availability of local suppliers, and it requires developers to forge strong relationships with suppliers.

Leveraging Offtake Expertise. As renewable-energy tenders become increasingly competitive, developers that can demonstrate expertise in structuring and managing PPAs as part of their bids can gain a significant advantage. This is particularly true in markets where tenders are highly contested, such as the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand.

Developers experienced in structuring direct PPAs—where companies buy power directly from a renewable-energy generator—often have a particular edge over other players. These agreements are emerging as an attractive route to market in mainland China, Japan, and Taiwan. For corporate end users, direct PPAs provide long-time price certainty, the ability to meet sustainability targets, and potential cost savings, compared with fossil fuel-based agreements. And for project developers and investors, direct PPAs offer a stable revenue stream and access to a growing market segment.

To navigate the APAC renewables arena—and make the most of the region’s considerable potential—developers, investors, and operators need to adopt five key success factors. By building these factors into their plans, international players can gain entry to the world’s hottest renewable-energy market. Without them, players risk being left out in the cold.