Roughly 70% of all transformations fall short of their objectives, for a variety of reasons. But boards can make a meaningful difference in whether a transformation hits its target objectives—or falls short. The challenge is that success requires boards to expand beyond their traditional role and engage with the CEO and management team frequently and proactively. That puts directors in a new role—one without clearly defined responsibilities in an area where some may not have direct experience. Often, boards simply don’t know where or how to engage with management during a transformation.

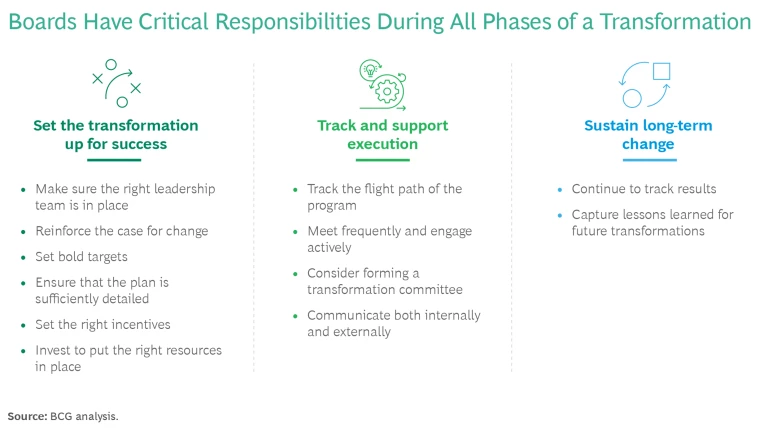

Our work supporting companies and boards during major change efforts suggests that the board’s role falls into three distinct phases: before, during, and after the transformation. At each phase, the board can make use of a set of measures to help management teams execute a transformation and help the company compete more effectively.

The New Mandate for Boards

Traditionally, boards focus on strategic oversight during steady-state operations, and they leave operational details to the management team. (For a company in direct peril, the board would be involved in a restructuring effort or turnaround, but those cases are rare.) In the current environment of continuous change, a board’s business-as-usual involvement is not enough.

Given how challenging the business environment is today—with cost pressure, high interest rates, geopolitical disruptions, new technology, evolving customer preferences, among other factors—companies need to launch more frequent transformations. These efforts are often spurred by the board, sometimes as part of a leadership transition when a new CEO takes over and sometimes because the company’s competitive position is slipping. In ideal circumstances, leading organizations don’t wait to be overwhelmed by these shifts; instead, they transform proactively, to improve financial and operational performance and strengthen their competitive position.

The challenge is that more frequent, comprehensive transformations require that boards work in a different way. Instead of simply recognizing problems and seeing that things need to change (the “what”), they must collaborate directly with the management team and with relevant subject matter experts to design and implement the change (the “how”). Directors must be far more hands-on, meeting frequently and engaging in subjects that they wouldn’t normally consider during steady-state operations.

We have identified a number of ways to support boards throughout a transformation. (See the exhibit.)

Set the Transformation Up for Success

During the planning phase, there are several critical areas where boards must engage with management and relevant subject matter experts to put the right foundation in place.

Make sure the right leadership team is in place. Most important, boards need to ensure that the CEO and overall leadership team have the right capabilities to implement a major transformation program. The capabilities needed to run a business are significantly different from those required to transform a business. Some CEOs, CFOs, CIOs, and other senior leaders may therefore need training and development in advance of the transformation. In other cases, the board may want to add a chief transformation officer to the C-suite and/or bring in outside partners, such as vendors with digital expertise.

Reinforce the case for change. The board must partner with the management team to clarify and articulate the case for change, using language that is clear, concise, and understandable at all levels of the organization. The board can also reinforce the case for change—both internally and (as needed) to any external stakeholders, such as shareholders or regulators. There should be no confusion or uncertainty about what is wrong and what needs to be fixed.

Set bold targets. Transformations can increase the stress on an organization, and the benefits must make the effort worthwhile. Rather than aiming for incremental improvements around the margins, boards need to work with the leadership team to set a high level of ambition, quantified by bold targets. At the same time, transformations need to include quick wins early on, to generate momentum and unlock value that can be used to fund subsequent steps in the journey.

Ensure that the plan is sufficiently detailed. The main reason transformations fail is not that companies don’t have a plan in place; it’s that most plans aren’t specific enough. Boards need to ensure that the transformation plan is more than a high-level summary. It needs to have the overall objectives broken down into clear workstreams, each with specific milestones, clear accountabilities, and explicit KPIs that link operational changes to financial impact.

The main reason transformations fail is not that companies don’t have a plan in place; it’s that most plans aren’t specific enough.

Financial KPIs are usually the main focus of board work, but they are backward-looking; by the time a company’s numbers are reported, it’s past the end of the quarter and too late to make meaningful changes. In a transformation, a forward-looking flight path of predicted impact, based on detailed milestones, is critically important.

Set the right incentives. Among the most important factors in a transformation’s success are leadership incentives. The remuneration committee should ensure that incentives are adjusted in advance of the transformation, linking financial rewards to clear benchmarks and transformational objectives. These should be both short-term incentives (typically quarterly) and long-term incentives (at least three years) to balance the short- and long-term performance of the company. The compensation for external subject matter experts should be structured in a similar way—with clear links to performance benchmarks.

Invest to put the right resources in place. Most transformations entail significant one-time costs along with other investments—often capex such as IT infrastructure but also investments in capabilities and competencies, such as leadership training programs and upskilling and reskilling initiatives for the workforce. Well-designed transformations build early, quick wins into the timeline, to free up capital that can fund subsequent phases, but virtually all transformations require an upfront investment. The board must commit to making these investments so that management has the resources it needs.

Track and Support Execution

Once the transformation launches, the board shifts to tracking implementation, which is particularly critical to get right during the first 100 days.

Track the flight path of the program. The biggest priority is to ensure that management reports results regularly and in sufficient detail, so that the board is fully aware of the status of the program. The overall plan will have thousands of KPIs across workstreams, and the board can’t—and shouldn’t—track execution at that level of detail. But it should have a sense of the most critical five to ten performance metrics, both in terms of transformation impact and their implication for the bottom line. Armed with those numbers, the board should be able to predict the company’s performance over the next one to two quarters and make early adjustments to ensure that the transformation succeeds.

Moreover, the board should expect the plan to be revised over time in response to changing market conditions and lessons learned. Accordingly, the board and C-level leaders should review the plan every six to nine months and remain flexible, adjusting priorities as needed.

Meet frequently and engage actively. Board meetings are typically bimonthly or quarterly, but during a transformation boards need to engage far more frequently with the management team and any relevant subject matter experts. (When Nokia transformed from a manufacturer of mobile phones to a manufacturer of telecom infrastructure, the board meet 63 times in one year.) In addition, board discussions will have less of their usual high-level strategic orientation and will instead be focused on the operational details of the transformation, as well as on specific problems and the interventions needed to keep it on track.

Consider forming a transformation committee. Involving the full board in the details of a transformation can be challenging. Some boards nominate two to three members to run a transformation or program oversight committee. In the early phases of the program, the committee meets with the CEO, CFO, and CTO every two weeks. It relays the board’s perspective to those leaders and reports back to the rest of the board, serving as a liaison so that all directors understand the current state of the program.

Communicate both internally and externally. Transformations are disruptive, which can put a strain on employees, investors, and other stakeholders. Boards can play a crucial role in reassuring these groups through frequent, clear, and consistent communication about the goals of the transformation, what it’s going to require, and how the company is tracking progress.

Sustain Long-Term Change

The typical transformation includes a very intense, core period that lasts 18 to 24 months, but the project doesn’t end after that hard work is over. Specific measures can ensure that performance improvements and new capabilities take root.

For boards, the main objective is to ensure that gains in operational and financial performance are lasting.

Continue to track results. All too often, the short-term gains generated during a transformation disappear after it ends. Costs creep back in, initiatives lose momentum, and employees revert to familiar ways of working. For boards, the main objective is to ensure that gains in operational and financial performance are lasting. Boards need to get continued reports from the management team, including both financial and operational KPIs.

Companies also need to root the practices and lessons learned during the transformation into the company’s culture, so that the capabilities required to make and sustain change are hardwired into the organization. To that end, some companies retain their transformation management office, albeit at a reduced level of activity, in order to ensure continuation of core change management and transformation capabilities.

Capture lessons learned for future transformations. Transformations should include a retrospective look at what worked and what didn’t, so that the company can improve its change management performance over time. Critically, that may mean looking at ways the board itself can incorporate new capabilities, potentially by bringing in directors who have expertise in critical areas.

Given the need for continued reinvention, companies are now in a mode of “always on” transformation. Boards are uniquely positioned to help, provided they engage with the management team more frequently and actively, and at a greater level of detail, than they do during standard steady-state operations. By taking specific steps before, during, and after the transformation, boards can help it succeed—and position the company to compete more effectively.