Are bioproducts made from precision fermentation processes—long predicted to disrupt industries from pharmaceuticals to food to chemicals—finally on the verge of achieving their potential?

Demand is solidifying. The need to achieve sustainability in manufacturing while reducing carbon emissions means that all kinds of companies need ingredients and inputs produced through biological processes. More than 4,100 of the world’s largest companies have established emissions-reduction targets, according to the Science Based Targets initiative, with more than 2,600 of them including net zero emissions commitments. The Biden Administration has set a target of producing “at least 30% of the US chemical demand via sustainable and cost-effective biomanufacturing pathways” within 20 years.

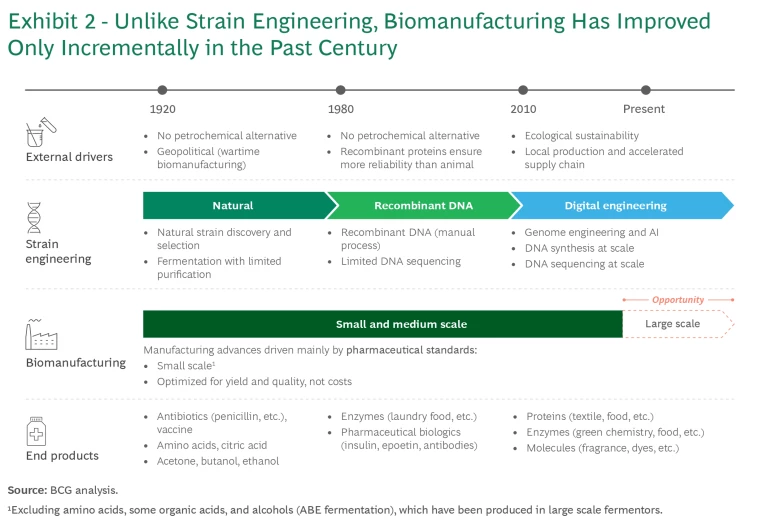

There has been great progress in the lab, with the development of new molecules and genetic strains. The big barrier to broader adoption so far has been biomanufacturing costs. With the exception of pharma—whose business models are mainly built on high-margin, low-volume products with low sensitivity to costs—and a few other product categories, precision fermentation and biomanufacturing have not yet proved to be economically viable at commercial scale.

Scaling the Solution

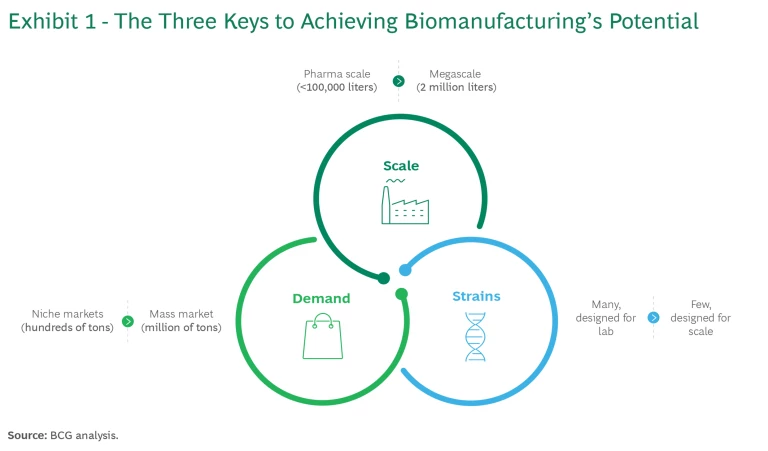

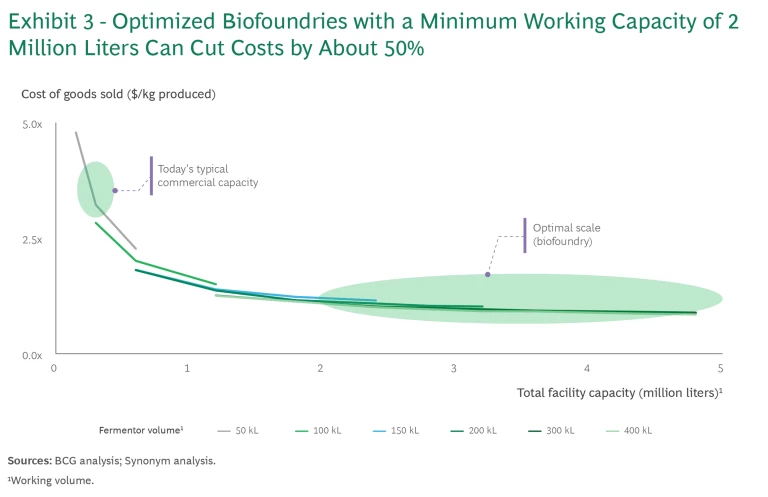

Enter biofoundries—facilities that are designed, built, optimized, and standardized for efficient and economic production of nonpharma bioproducts. Each such facility can provide at least 2 million liters of capacity, achieving commercial economics and bridging the cost gap for large production categories such as food and biomaterials by reducing unit costs by 50%, enabling some cost parity with incumbent technologies. (See Exhibit 1.)

More advanced facilities, along with improved strains, could reduce production costs by up to 90%, achieving or surpassing price parity with current incumbent methods for most products. (See Exhibit 2.)

We estimate that the market for biomanufactured ingredients in just three industries—specialty chemicals, food, and chemical precursors—could reach $200 billion by 2040, assuming that the manufacturing capacity is in place. In fact, market sizing estimates by others have run into the trillions of dollars. We are focusing only on the market for the bioproducts produced by the new biofoundries in these three categories, which are most often used as ingredient inputs, and not on the market for formulated finished products. Standardized biofoundries can serve all of these markets, with construction focusing on higher-margin, lower-volume molecules first. (See Exhibit 3.)

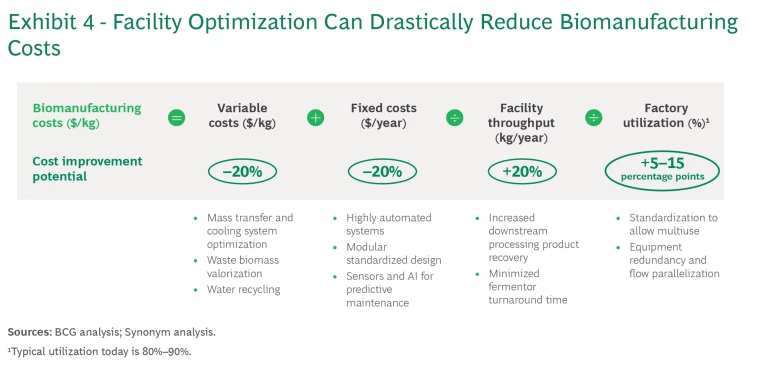

BCG’s new report, prepared in collaboration with Synonym—a developer of physical, digital, and financial biomanufacturing infrastructure—details how biomanufacturing can finally fulfill its promise of achieving commercial scale. Some of the necessary innovations, such as the use of AI and high-precision sensors, will require advances in technology, but many involve only cost optimization related to process engineering. These levers focus on such high-cost items as energy demand and labor and maintenance, and companies can apply them today.

Standardization and optimization provide biofoundries with significant advantages over existing large-scale biomanufacturing facilities, particularly with respect to cost, timeline, and adaptability. The bespoke nature of traditional facilities results in elevated costs and prolonged timelines.

In contrast, standardized biofoundries have the potential to reduce costs and construction times. Initial facilities are expensive but they offer multipurpose functionality and adaptability. Standardization can reduce the capital investment for later biofoundries by up to 30%. This approach not only mitigates risks but also helps make biofoundries a versatile solution that can meet evolving needs and advances in future strains.

Barriers Remain

There are still challenges. Next-generation facilities do not yet have a track record, and they require upfront capital investment of $300 million to $400 million each, depending on exact specifications. The stages of design and construction take three to five years to complete, at least for the first facilities. These factors make raising capital difficult without committed demand.

Widespread customer education and new rules and regulations are key, particularly in the food industry. Regulatory authorities such as the US FDA and the European Food Safety Authority must develop new validation and inspection rules and procedures to facilitate the development of new, sustainable, and safe products without increasing time-to-market. But the need to combat rising temperatures and greenhouse gas emissions will make major manufacturing changes mandatory. In addition to reducing emissions by using biogenic rather than fossil-derived chemical inputs, biofoundries improve yield and energy efficiencies, thus making biomanufacturing at scale a more appealing alternative for producing most molecules from the standpoint of CO2 emissions. (See Exhibit 4.)

Breaking through the cost conundrum will depend on investment coalescing behind standardized designs for biofoundries. Our estimates show that serving a $200 billion market requires a 20-fold expansion of current production capacity. This is a massive challenge, but it is not out of reach. Bioethanol, which represents 10% to 15% of US gasoline consumption, has almost reached parity prices with fossil fuels in a single decade (thanks in part to governments mandates) and has built the infrastructure to sustain a $100 billion market.

An Emerging Asset Class

The shift to large-scale, standardized biomanufacturing sites represents an enormous opportunity for infrastructure investment—and the potential for an emerging asset class. In large, capital-intensive projects, demand typically anticipates supply through contracted offtake agreements. These agreements, which are common practice in chemicals and specialty chemicals, are likely a prerequisite for investors to finance facilities and production line setups.

Although some pilot facilities and a few commercial-scale facilities have been built, standardizing the asset class in line with offtake demand will unlock capital from later-stage investors. Facilities can be built today to handle the strains of tomorrow, and standardization and replicable designs will drive a reduction in capex and construction timelines. Thanks to advances in biomanufacturing and a focus on nonpharma bioproducts, Synonym has designed a highly standardized facility for which 80% to 90% of the capex goes to facility elements that are applicable across many precision-fermented products. Only 10% to 20% is for molecule-specific equipment. As a result, investors and funds that specialize in infrastructure investments can approach biofoundries as a single asset class in which each project has very similar specifications and requirements.

Precision fermentation has demonstrated its potential time and again. The key question now is whether biomanufacturing can overcome the cost-scale conundrum and support a broad-based shift to more sustainable alternative processes that can unlock big new products and markets. Large companies looking to meet their sustainability goals need to act now to transform their supply chains by committing to purchase bioproducts. Far-sighted investors with a focus on infrastructure should evaluate the emerging asset class and be ready to commit capital to attractive projects.

The authors would like to thank Nicolas Goeldel and Max Richly of BCG, Joshua Lachter of Synonym, Per Falholt of 21st.BIO, Gwenaël Servant of Abolis, and Céline Crusson-Rubio of SICOS for their contributions to this publication.