Few industries have more experience in removing costs than oil and gas exploration and production (E&P). But costs also have a way of creeping back in as priorities shift over time—toward maximizing production or re-emphasizing maintenance, for example—and before long, costs need to be addressed again. Oil and gas also are volatile commodities, and companies feel the effects of external factors (inflation and supply chain interruptions are two current culprits) hard.

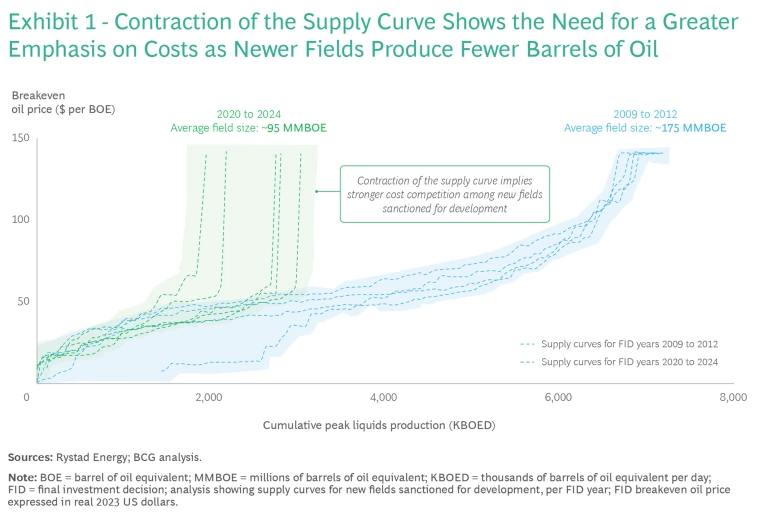

Our current client work indicates that the industry is again feeling the cost pinch. Some companies have sworn off new exploration in favor of alternative energy strategies, putting a premium on maximizing the value of current production. Many of today’s discoveries are expected to yield fewer total barrels than those in the past, making costs a bigger factor in profitability. (See Exhibit 1.)

The question companies should be asking now is, How can we take costs out of the system permanently? And how do we make cost savings sustainable?

We are seeing some companies come up with innovative—and high-potential—answers. Here’s what they are doing.

The question companies should be asking now is, How can we take costs out of the system permanently? And how do we make cost savings sustainable?

Cost Drivers and Solutions

Upstream operating expenses (opex) depend on a stable set of factors: people, engineering, supplies, and logistics. Little changes in the makeup of these costs because companies follow similar operating philosophies that establish procedures for common processes and practices.

These include rotational site-based crews supported by off-site personnel, the logistics surrounding transfers of crew and materials, managing backlogs of work orders requiring execution, and maintaining or increasing well flow. To make significant changes to the cost base, companies need to think differently about each of these elements and how they are willing to address them, consistent with concerns regarding safety, asset integrity, and, increasingly, carbon intensity.

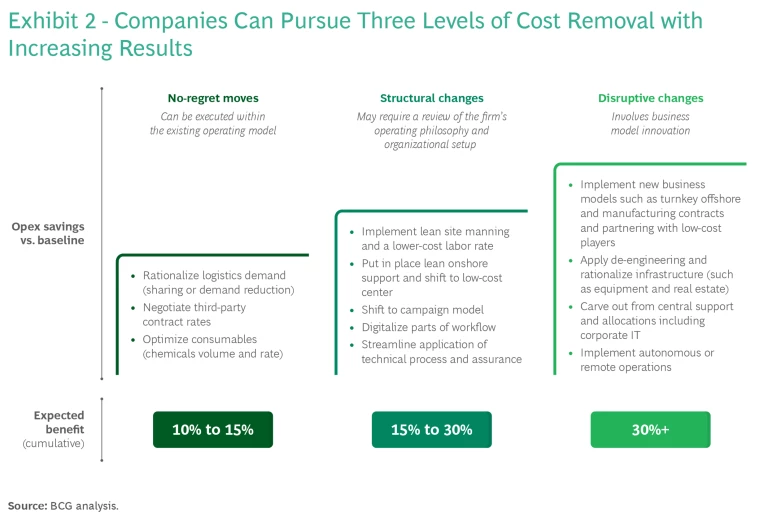

Producers typically approach costs at three levels of increasing complexity, depending on the extent of their ambition: “no-regret” moves, structural changes to the asset operating model, and making changes that are more disruptive. (See Exhibit 2.) The most aggressive companies have registered savings of more than 30% of opex. Such programs can also have a positive spillover effect on safety, carbon-emissions, and production outcomes. By taking work out of the system and delivering it differently, companies often benefit from reinvigorated cost consciousness in the organization. This can help cement business priorities and salient risks, allowing for a more focused effort around these outcomes.

No-Regret Moves. These efforts deliver improved efficiency within current company structures. They typically drive higher efficiency from inputs and can deliver savings of 10% to 15% of opex. One operator realized a 20% improvement in the productive time of offshore crews through a more efficient permit-to-work process. Another rationalized specifications, use, scheduling, and routes for its fleet of marine vessels (including platform supply vessels, fast crew boats, work boats, and tugboats) to reduce marine costs by 20%.

Common no-regret moves include:

- Rationalizing demand for logistics support (for example, taking a vessel or helicopter out of the schedule)

- Reducing consumables (such as the volume and rate of chemicals usage)

- Streamlining the application of permit-to-work processes, which can lead to 15% to 20% increases in actual work time

- Reviewing the necessity of maintenance work orders (and taking lower-risk work out of the system)

- Optimizing contractor spending on materials and services through more stringent management of demand, such as by renegotiating long-term incumbent contracts and moving to more incentive-based contract structures

Structural Change. This level of improvement involves more complex changes to the operating philosophy or ways of working for the asset. Steps include fit-for-purpose site manning (which challenges traditional 24-7 expat or specialist-capability rotations) and lean offsite support that optimizes such factors as the size and extent of support, the mix of labor rates, and the location from which the site is serviced. More aggressive companies have digitized parts of their workflow or outsourced them to lower-cost locations and providers.

These changes are about how the work is done, and they need to be codified in workflow and process adjustments. For example, a campaign-based approach to maintenance involves packaging work into fixed short-term scopes that do not require crews to be constantly onsite. For one North Sea operator, moving to a campaign approach for maintenance led to a 10% to 15% scope reduction, a 5% to 10% workload reduction, and 10% to 15% productivity improvement across its assets.

Another enabler involves orienting the asset to a simple set of value-based metrics that adequately reflect the importance of cost (such as the lowest cash flow breakeven price or opex per barrel). Companies should prioritize tasks, suspend non-priority work, and make sure high-value work is adequately resourced and managed to a firm cost target.

Zero-based site manning (building the staffing levels of operational sites based on essential activities and workloads, rather than using historical staffing levels) and the outsourcing of operation and maintenance contracts for floating production storage and offloading have shown potential for labor cost reductions of 30% or more. (See the sidebar “Making Structural Cuts to Labor Costs.”)

Making Structural Cuts to Labor Costs

The company chose an integrated approach to revamping its operating model, starting with transforming its operating philosophy. It defined a clear split of duties for core crew and campaigns, established a team to manage critical activities, and built multidisciplinary skill sets among crew, such as those delivering first-level maintenance. It also redefined governance and streamlined core processes to prepare, plan, and execute operations and campaigns onsite. It set up an integrated operations center onshore, with digital monitoring and intervention capabilities, to supports the onsite teams for production, planning and scheduling, maintenance, and logistic activities, enabling a lean, fit-for-purpose personnel approach.

Defining a fit-for-purpose scope and volume of activities allowed the company to reduce ambiguity by adjusting the balance of corrective and preventive maintenance; assessing the necessity of activities, equipment, and installations; and utilizing advanced analytics to optimize future maintenance demand. It also optimized demand management by modularizing tasks across operations, production, fabric maintenance, and maintenance activities.

With the new model, the company was able to achieve close to a 40% reduction in onsite staff and an annual savings of more than $100 million across four assets.

Disruptive Change. These changes require a new operating approach and innovative business models. For example, some companies, such as bpx energy, Equinor FLX, and Eni (through its satellite strategy), have carved out parts of their portfolios as standalone entities to drive higher asset centricity, focus, and control, especially with respect to overheads and procedures. In practice, these entities can be operated as separate businesses (as in the case of bpx energy), or as an independent business unit with a dedicated board of directors (such as Equinor’s FLX). They can also be spun off into another company with the parent retaining a minority stake, similar to Eni’s satellites with Azule Energy in Angola, Vår Energi in Norway, and a potential combination with Ithaca Energy in the UK.

Another approach is to simplify and rationalize the engineering set up. Operators can strip asset equipment down to essential capacities and remove unneeded contingencies, lowering the need for operational and maintenance oversight and cutting costs with fewer tradeoffs.

In other cases, joint ventures within companies have moved to control their overhead in radical ways, such as outsourcing tech support to third-party providers, shifting from enterprise resource planning to lower-cost cloud-based systems, or providing employees with allowances to purchase their own laptops for work. Additional strategies include building cost reductions into the supply chain, such as by outsourcing the operation and maintenance of an asset to a third party with a contract that incentivizes performance without sacrificing safety and integrity. This approach has yielded some firms up to a 30% cost improvement.

With more disruptive changes, companies need to take care that they really are removing costs and are not simply “squeezing the balloon” by reallocating them elsewhere.

With more disruptive changes, companies need to take care that they really are removing costs and are not simply “squeezing the balloon” by reallocating them elsewhere.

Making the Cuts Stick

Despite the proven potential of the measures outlined here, many upstream producers struggle with successful and lasting implementation. To achieve sustainable cost reduction, operators must embrace an integrated approach that incorporates non-traditional methods, collaboration among functions, and discipline across the organization. Key changes include:

- Understanding and Adjusting How Work Gets Done at the Front Line. It’s crucial for companies to genuinely grasp how work is delivered onsite before designing the kinds of changes that can improve efficiency and effectiveness on a continuing basis.

- Challenging “Accepted and Tested” Standards and Practices. Management needs to challenge standards that have acquired “gold-plated” status in the name of risk mitigation, especially when the asset’s remaining economic life doesn’t merit the associated expenditures.

- Fostering Interdisciplinary Collaboration and Skill Sets. Sustained cost control is a multidisciplinary effort. Teams need aligned KPIs, collocation, and agile methodologies to ensure that they work toward common goals and enhance operational synergy.

- Developing a “Bias for Value” at All Levels of the Organization. Costs should be top of mind. Companies can encourage the development of a value-oriented culture by ensuring that every level of the organization contributes to the overarching goal of cost efficiency, without compromising performance on production, integrity, or health, safety, and the environment.

- Instilling Disciplined Management of Change. The rigorous management of change, not only at the initiative level but also across programs, is essential to managing interdependencies and ensuring coherent progress.

- Follow Leading Indicators to Guide Transformation. Part of management’s role is to continuously monitor and adjust the transformation process using leading indicators that track progress and effectiveness, ensuring that the journey toward cost reduction is measurable and controlled.

Key to the success of any cost transformation is approaching each step from an investor’s point of view. Sustained cost control requires a comprehensive perspective and a concerted effort across all aspects of operations. The challenge for E&P companies lies not in the novelty of cost-saving measures but in applying them in a persistent and integrated way across the entire organization.