Joint ventures (JVs) between two or more companies have proven to be a highly effective way to develop new business opportunities or expand into new markets. Yet companies have also encountered barriers to achieving the value creation that these partnerships should deliver. It is especially important to overcome these barriers now, as a well-structured joint venture can often be more resilient than a traditional acquisition when it comes to riding out uncertainties in the global economy.

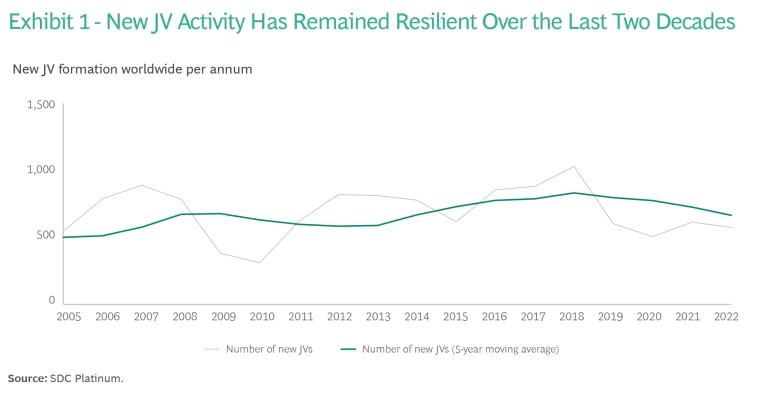

JV activity has remained strong over the past two decades, rebounding after the financial crisis and the pandemic shook global markets. (See Exhibit 1.) The resilience to date may be, in part, a function of the advantages that joint ventures present.

For one thing, a joint venture offers a great deal of flexibility. It is often set up as a temporary structure. The timeframe can be five years, ten years, or however long it takes to achieve the intended goals, and when the time comes, a well-designed JV can be unwound efficiently. In addition, there are far more options for implementing a JV structure compared to those for M&As—and the structure itself can be adapted to specific situations and market conditions. Moreover, the partners in a JV share capital, resources, and at least a degree of business risk, making these vehicles a particularly attractive alternative to an outright acquisition in challenging times.

The continued demand for JVs has also been a function of internationalization , as companies have sought to expand their geographic presence and capture opportunities in rapidly growing emerging markets. Having a local partner in these markets is often key to successfully navigating unfamiliar territory. In some cases governments even require that, in order to do business in the country, foreign companies must set up partnerships with a local business.

In 2023, nine years after BCG first undertook an extensive survey on the state of value creation in JVs, we conducted a new survey to see how the climate has evolved. We received responses from 159 business executives around the world, all with strategy or M&A roles in companies that operate JVs representing a wide range of industries and geographies. (See Appendix .)

Our research found that business leaders now consider JVs more important than ever, with one in two respondents now saying they believe JVs are becoming more relevant than traditional M&A to their companies’ strategies. A majority (60%) said that compared to outright acquisitions, JVs are more resilient vehicles in times of economic downturn, while 58% said the current geopolitical landscape favors establishing JVs over M&A.

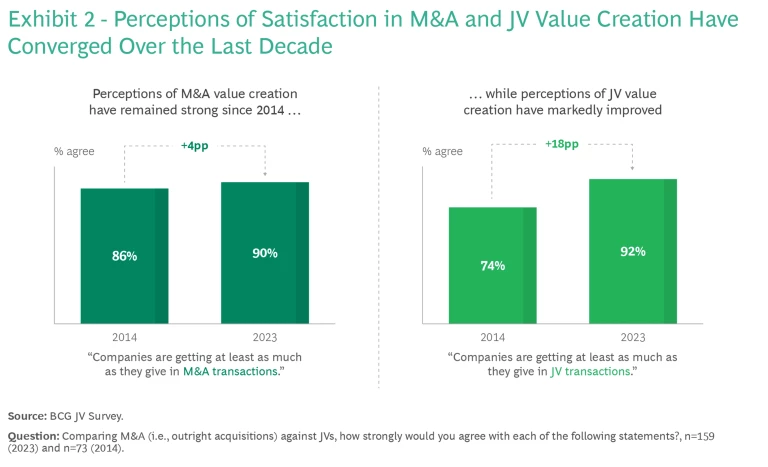

Business leaders have also become more satisfied with the level of value creation they are achieving from JVs than they were ten years ago. The vast majority (92%) said they had received at least as much value from their JVs as they contributed, versus 74% in 2014. What is particularly noteworthy is that the level of satisfaction with JVs has nearly converged with that of M&A deals. (See Exhibit 2.)

Still, many business leaders believe that they could achieve more value; 83% of respondents still feel there is room for further improvement—a figure that remains very material even if lower than in 2014, when 92% reported that the value created by their JVs could be better.

What Creates Value?

There are, indeed, a number of reasons that a JV might not realize all of the value that it could. Operating a JV is generally more complex than operating an acquired business. In fact, more than half of our survey respondents said their senior managers believe it is easier to operate an acquired company than a JV. And only 28% said it was easier to add value through a JV, as opposed to 41% who said they found it easier to add value with an acquisition.

In an M&A deal there are usually only two parties—the acquirer and the target. Once the parties agree that they want to complete the deal, the terms of discussion tend to revolve mostly around the price. Then, ultimately, the two entities become one, with the acquiring company in charge. A JV, on the other hand, requires the ongoing participation of at least three parties—the two (or more) parent companies plus the joint venture subsidiary—for the life of the partnership.

The limits to value creation often begin when the parent companies don’t design a specific strategy for addressing these complexities. In our research, we saw a close correlation between the value generated by a JV and the resources, talent, and management attention that the partners commit to the venture. The finding that so many key executives are not fully satisfied with their JV value creation appears to be symptomatic of underinvestment—particularly of human capital—in comparison to M&A deals.

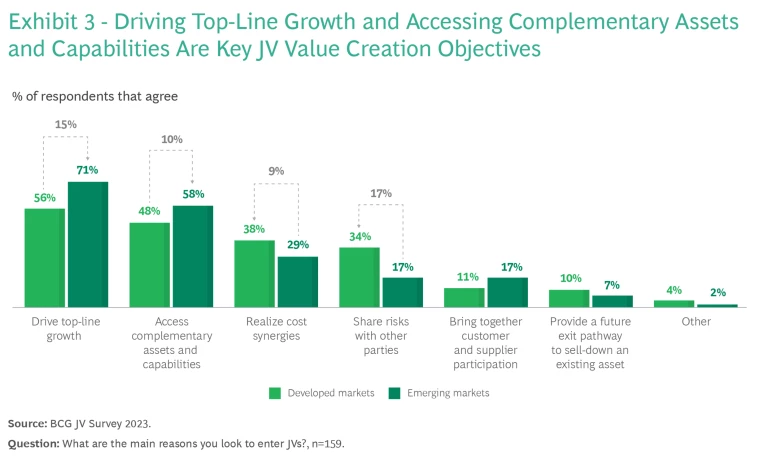

It is also important to consider what companies are seeking when they set out to form a JV. The two primary motivating factors that more than half of our survey respondents cited as reasons for entering into a JV are driving top-line growth and accessing complementary assets and capabilities. (See Exhibit 3.)

These objectives are particularly pronounced in JVs based in emerging markets. For example, North American and European firms have been entering into JVs with local partners in India and China since these countries began opening up to the private sector in the 1980s and 1990s, with the goal of harnessing market growth and benefitting from the local partner’s established customer and sales channels. Meanwhile, the local partner in most emerging market JVs expects to gain new capabilities from the foreign partner’s technology expertise or intellectual property (IP) to better capitalize on their domestic market growth. This was an objective cited by many respondents from the Middle East and Africa (MEA) as well as the Asian-Pacific (APAC) region.

In developed markets where the economy is more mature, JV partners still see growth and complementary assets as important objectives. However, they also tend to expect value creation through the cost synergies that come from combining market operations as well as from sharing business risks.

Investing More Resources Creates More Value

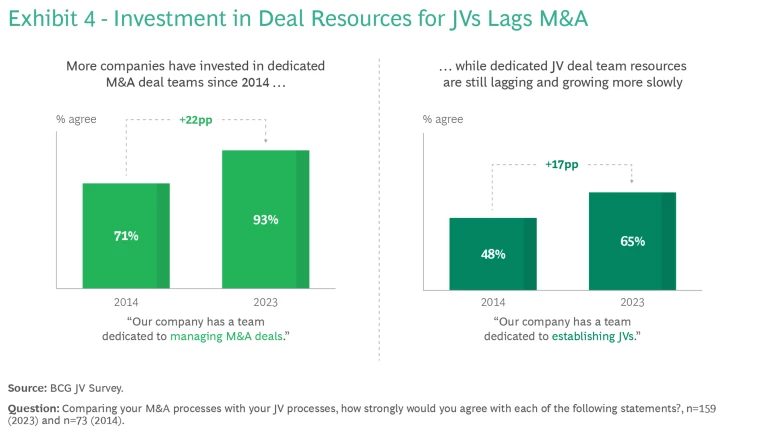

Wherever a JV is based, the partners need to make a strong commitment that includes both funding and capabilities. One indication of underinvestment is that more than 90% of the executives we surveyed said their companies have teams dedicated to M&A deals, while only 65% have teams that focus on establishing JVs. (See Exhibit 4.)

Investment also lags in the resources needed to operate the venture once the deal is completed. Since 2014, companies’ incremental investment in post-deal resources for implementing and operating JVs has been half that of the resources deployed to integrate acquired businesses. This is not only a question of quantity but also of quality when it comes to top-caliber talent and senior management attention. Of the executives we surveyed, 84% said their M&A teams were staffed with the best talent, while a smaller number—only 72%—said the same of their JV teams.

In fact, we have seen a number of cases in which a company’s M&A team is put in charge of JVs more or less by default, without the tailored capabilities necessary to address the unique needs of a JV. Historically, M&As have been the main source for deals and continue to yield a greater deal flow than JVs, so it is understandable that when companies need to ration their resources they are likely to prioritize M&A transaction teams. However, when a business enters into a JV without enlisting people who are experienced in running this particular kind of partnership, it will be harder to resolve the complexities that come with operating the new entity. The result might be a self-reinforcing cycle of dissatisfaction with the value that is unlocked.

Overcoming Obstacles to Value Creation

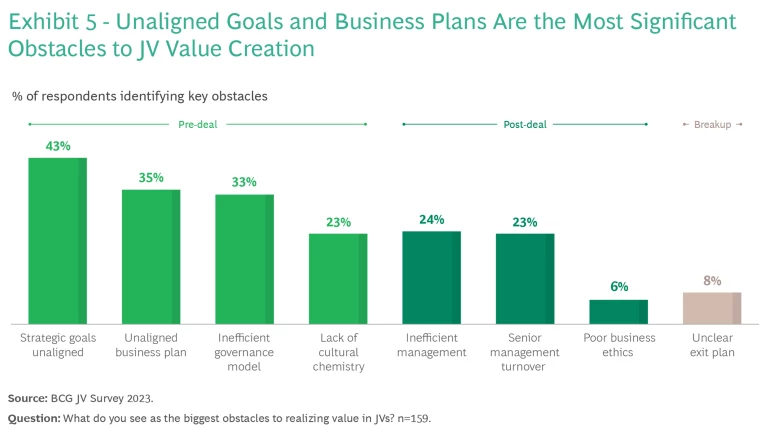

The participants in our survey discussed a number of obstacles they’ve encountered that make it more difficult to create value from the complementary assets and capabilities of the JV partners. By far, the biggest value destroyers cited were misalignment in the strategic goals and business plans aimed at realizing value in the first place, along with—for some regions—inefficient governance models. (See Exhibit 5.)

It is telling that what survey participants consider to be the biggest obstacles are in the pre-deal phase. Yet any of these obstacles can deprive a JV of realizing its full potential value. It is therefore important to address all of them right from the beginning.

We’ve seen that, as with other global partnerships BCG has examined, lack of alignment of the JV partners’ strategic goals and business plans can cause unnecessary complexities in an already complex arrangement. This can lead to a situation in which partners mistrust each other and have a disincentive to commit the necessary resources—ultimately making it difficult for the JV to reach its full potential for value creation. A well-structured partnership agreement, however, can eliminate such obstacles and result in a more successful JV. Specifically, we recommend five best practices that will facilitate continued resilience throughout the life of the partnership.

Ensure upfront alignment on strategic objectives and plans.

When considering a partnership, start with a discussion in which each party is clear about their objectives. If your potential partner is trying to cut costs while your company is eager to invest in growth—or one is anticipating a quick pay-back period while the other is willing to make a 10-year commitment—you are unlikely to come up with a set of aligned goals for the partnership. Begin the discussions with an honest list of the objectives that are most important to your business. From there, design a joint business plan for the next three to five years that includes key investment and return expectations. This will help establish a solid foundation for the early years of the partnership.

Establish a clear governance structure.

You and your partner(s) should agree on key governance measures such as operational decision-making, parent company oversight, leadership structure, balance of roles and accountability, compliance, risk management , and administration. The governance setup should provide a clear pathway for agile decision-making and escalation of disputes so that the venture isn’t hamstrung by stalemates between the partners or excessive bureaucracy. With this structure in place, the parent companies will be in a position to provide regular direction when needed without having to micromanage the venture.

Commit management time and support in addition to funding.

Once launched, a JV has a life of its own, and all partners need to contribute the resources that will accelerate its growth. More often than not, this means hands-on involvement, not just financial capital. It’s important to recognize that in a JV you haven’t simply divested a piece of your business; rather, you’ve merged it into a greater whole and essentially acquired a piece of your partner’s business. To realize the full potential of this larger entity, each partner should expect to bring an “investor mindset” to the table. That means contributing top talent and assets in such areas as IP, technology, and sales, along with the go-to-market access that will be key to the venture’s growth.

Overinvest in collaboration to build chemistry with your partner.

Nearly a quarter of our respondents cited lack of cultural chemistry as a barrier to success. This is not surprising, since even the most detailed business plan will not come to fruition if the partners can’t get along. Given that in many JVs two or more businesses on opposite sides of the world must come together, it’s critical that you put considerable effort ahead of time into building the relationship, especially making sure that the executives who will be leading the JV can work well with one another. It is also critical that the JV managers view themselves as the leaders of the combined entity and their objectives are aimed at building value for the JV, as opposed to thinking of themselves as the executives from “Partner A” versus those from “Partner B.”

Align upfront on exit mechanisms and scenarios.

The timeframe for the venture’s existence will vary depending on your purpose and goals, but ultimately most JVs come to an end. All parties should envisage this outcome upfront, modeling potential scenarios and planning accordingly. Unlike an M&A deal, in which the sole parent company can sell off the acquired business if it isn’t working out as planned, a JV needs exit mechanisms that allow each party to bow out or renegotiate the contract if things go wrong.

Even if the partnership produces all of the projected value in the anticipated time and the partner relationships remain excellent, a comprehensive exit plan assures that when the venture has served its purpose the breakup will be harmonious. There are many options for an exit: for example, you can wind the entity down, sell it to a new owner, sell one partner’s stake to the other partner(s), or take it public. It is crucial, however, that all partners agree on how you will determine the end of the venture—and the mechanism for valuing it at the time of exit—before the actual launch, at a time when your partner relationships are certain to be more constructive.

The success of a JV is highly dependent on the discussions that happen before the deal is signed. Whereas an acquisition might be easier to operate because the acquiring party is responsible for all of the strategic decisions, a well-designed JV can often realize even greater value with less risk and lower operating costs. The key to maximizing value, however, lies in both parties applying an investor mindset, recognizing the hurdles that must be addressed, and committing the necessary resources and vision. This kind of full-scale support is the key to unlocking the true potential of a joint venture.