For the CEO

Business revolutions bring unexpected challenges, and the two gripping the world right now— GenAI and the energy transition —are no exception. But the hurdles they present are interconnected. And how CEOs respond could well determine whether one revolution becomes the other’s undoing—or together, they help move the world toward a more sustainable, prosperous future.

For years, tech giants have been at the vanguard of corporate action on climate, with some pledging to reach net zero by the end of this decade. But the rush to develop AI is throwing that timeline into doubt. After decades of stagnant growth, US energy demand is surging, thanks in large part to the power-hungry chips and data centers that AI hyperscalers—the tech companies at the forefront of AI development—need to train large language models (LLMs) and embed AI into consumer-facing applications as well as the steady migration of business operations to the cloud.

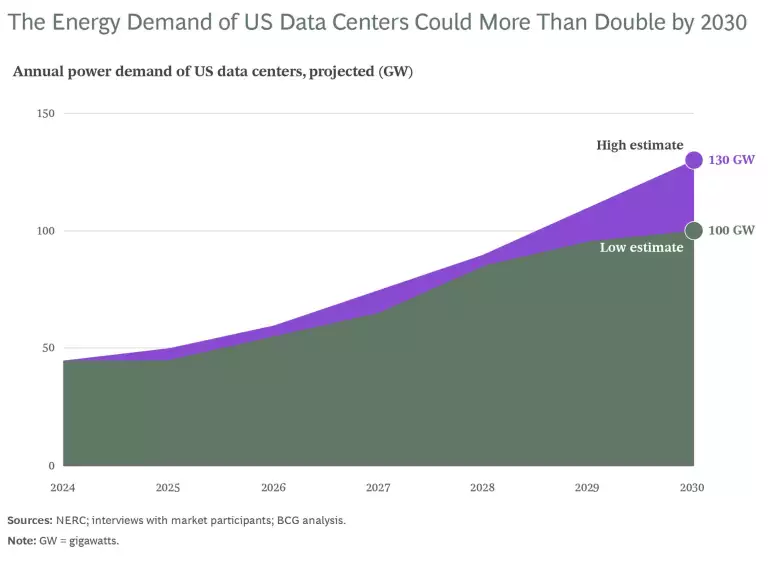

Moreover, AI’s thirst for energy is set to intensify. Electricity demand for US data centers is projected to rise by 15% to 20% annually, reaching 100 to 130 gigawatt hours in 2030, according to BCG analysis. That’s enough to power two-thirds of US households.

That trajectory would seem to put GenAI development—and its promise to drive productivity improvements and economic growth—on a collision course with carbon reduction efforts. But the dynamic that’s unfolding could prove far more symbiotic.

“The positive side of it is we can use that as an impetus to spur the development of low-carbon technologies,” says Maurice Berns , a BCG managing director and senior partner and the chair of its Center for Energy Impact.

Keeping climate and AI development goals on track is possible, but no single CEO or policymaker can do it alone. Energy companies, AI hyperscalers, and end users will need to work individually and in concert to develop near-term strategies and longer-term solutions that are both climate-friendly and maintain an AI advantage.

Navigating a Near-Term Power Crunch

Data centers could contribute more than 60% of incremental US power demand through the end of this decade, according to BCG estimates, with the rest coming from the electrification of transport, buildings, and other industrial endeavors.

At that rate, the US could see a shortfall in “firm” power—power that is available at all times, regardless of conditions—as soon as 2026. That’s enough time to get new power-generation projects off the ground, but not enough to complete them. Transmission lines alone can take up to 10 years or more to site, permit, and build.

Improvements in chip designs are also unlikely to ease a potential power crunch. “The energy efficiency of chips is getting better, but AI companies will likely use those improvements to increase performance rather than reduce power,” says Vivian Lee , a BCG managing director and partner. “If we see a shortfall [in firm power], it can really only be serviced in the near term by things that are available now—primarily carbon-emitting energy infrastructure.”

Lee believes the near term can include a pathway to carbon sequestration, a technology energy companies are investing in. And given that shortfalls will likely vary across regional power markets, she sees ripe opportunities to deploy excess capacity where needed.

Stay the course on what you need to do to make AI successful, and ensure that you’re keeping an eye on the cleanliness of the power you’re leveraging in your Scope 2 and 3 emissions. — Vivian Lee

AI hyperscalers can also pursue multiple avenues for optimizing energy consumption now.

“Instead of training only very large language models, they can invest in smaller ones that are less energy greedy,” says Nicolas de Bellefonds , a BCG managing director and senior partner. “They can optimize the architecture of data centers to consume less energy for computing and cooling and also be thoughtful about where they locate them.”

Hyperscalers can even work with energy providers by adjusting data-center workloads around peak demand times and developing AI solutions for optimizing power grids.

End users, too, can make strategic moves to ensure their AI transformations and climate goals don’t get derailed. “Stay the course on what you need to do to make AI successful,” says Lee, “and ensure that you’re keeping an eye on the cleanliness of the power you’re leveraging in your Scope 2 and 3 emissions.”

Finally, after decades of relatively low electricity prices, all companies should prepare for higher costs. “We are in a massive [power-] building phase,” says Berns. “The cost of energy will need to go up.”

Powering Tomorrow

Energy infrastructure doesn’t come cheap, and the imperative to meet rising demand sustainably is thrusting power-sector leaders into unfamiliar terrain. “Energy companies are not used to figuring out how to deploy capital at the pace that is now being asked of them,” says Lee.

But the type and volume of power AI hyperscalers want and need can eliminate a lot of the risk energy companies have historically shouldered when building new capacity.

“Hyperscalers need large chunks of base load locked in for a very long time, and they want lower carbon emissions,” says Berns. “That provides an impetus for technology development and the kind of deals we’re already seeing that eliminate a lot of financial and demand risks for generators.”

For years, big tech companies have supported renewables. But wind and solar provide intermittent electricity, not firm power. With AI power demands poised to grow, hyperscalers are looking to alternative sources of reliable, uninterrupted, low-carbon energy .

Microsoft recently struck a 20-year power purchase agreement with Constellation Energy that includes restarting a mothballed reactor at Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island. The estimated price tag for putting the reactor back into service is $1.6 billion.

Hyperscalers need large chunks of base load locked in for a very long time, and they want lower carbon emissions. That provides an impetus for technology development. — Maurice Berns

Google and Amazon, meanwhile, have inked deals to advance the development of small modular reactors (SMRs). Conceived as cheaper, faster to build, and safer than traditional nuclear reactors, operational SMRs have yet to move beyond the drawing board in the US. And as with all forms of nuclear power, concerns are likely to persist around the transport and storage of radioactive materials. But big-tech backing is giving SMRs the clearest pathway yet to commercial viability.

“We can’t ignore the risks around nuclear, but it gives us a line of sight to a scalable solution to deliver more base load power—and green power at that,” says Berns.

The more hyperscalers work with energy companies, the more innovation those efforts could foster. “They both have a role to play to help crack optimization and create the energy system of tomorrow,” says Hamid Maher , a BCG managing director and senior partner and head of the firm’s Africa tech hub. “That system will be distributed, autonomous, and make decisions so there’s zero waste.”

Some hyperscalers may evolve to design new energy solutions—or even become energy companies. “They could launch their own research facilities to figure out new ways to serve their energy needs,” says de Bellefonds. “Or they could say, ‘Well, I need energy, I’m going to get myself an energy network, and I will use 30% and the other 70% I will sell.’”

Power Moves for AI and Climate Goals

How CEOs of energy companies, AI hyperscalers, and end users respond to the rapidly emerging landscape will likely pivot on the regional contexts in which they operate. “You can have a global ambition, but the way you come at it in every region is so different,” says Berns.

For example, regulations could prioritize some climate technologies over others. Trade barriers could hinder access to key components. And in areas where energy infrastructure is woefully insufficient, behind-the-meter solutions—where end users generate their own energy—could prove more appealing.

More broadly, there are actions stakeholders can take now to manage pending near-term power issues and lay the foundation for a climate-friendly future.

Optimize now. CEOs can do their part to lessen a potential energy crunch by ensuring their firms are judicious with the electricity that’s currently available.

- Energy companies can help identify potential spare power generation and grid capacity by region. They can also explore how AI and other technologies can unlock greater grid efficiencies—for example, through grid-enhancing technologies and smart-meter data.

- Hyperscalers can optimize power consumption by deploying less energy-intensive hardware for inference—the process of putting AI models to work. They can also bring smaller models into play when appropriate, and they can work with energy providers to adjust consumption during periods of heightened demand on the grid.

- End users can continue apace with their AI transformations and encourage power savings by taking meaningful actions to measure, track, and limit their Scope 2 and 3 emissions.

Lay the groundwork for scalable, sustainable energy. While making the most of today’s electricity, CEOs can also lay the foundation to bring new, more climate-friendly power sources online by 2030 and beyond.

- Energy companies can help accelerate new climate-friendly energy infrastructure through forging agreements with AI hyperscalers, hastening capital deployment to address bottlenecks (such as transmission line construction), and engaging with policymakers and regulators to strategically design rate structure and funding approaches.

- Hyperscalers can continue to make strategic investments that absorb some of the financial risk energy companies have traditionally assumed to develop new energy technologies, such as SMRs. And considering the role natural gas may play in the energy mix going forward, they can also have conversations around technologies primed for commercialization, such as carbon sequestration.

- End users can put measures in place to rigorously track and optimize cloud costs, which in turn will optimize energy consumption and lower carbon emissions. They should also stay committed to their sustainability initiatives and demonstrate how those efforts translate into shareholder value.

CEOs of energy companies and those at the forefront of AI development and deployment stand at a critical juncture in modern history. The paths they choose now could well determine whether AI delivers as promised and the climate crisis is brought to heel. No single CEO has all the answers. But together, leaders can rise to the challenge, ensuring the AI and climate revolutions work in harmony.