As the world gathers for COP 29 in Azerbaijan, the road to net zero in carbon emissions is becoming more and more fragmented. The geopolitical landscape is shifting and morphing, moving away from global integration towards more multipolar terrain. Tensions are on the rise among competing priorities, including how to reduce emissions in the most efficient manner, maintain domestic political support for achieving net zero goals, capture the economic and job gains of green growth opportunities (while avoiding dangerous dependence on geopolitical adversaries), and maintain international solidarity for decarbonization .

Policymakers and business leaders need to assess emerging geopolitical realities and modify how they collaborate—and compete—across borders accordingly. All stakeholders need to come to grips with two questions. First, how do we accelerate paths toward net zero in a world defined by intensifying competition? COP remains a critical forum in this regard, perhaps taking on an even more important role as poles harden and countries grow further apart. And second, how do countries and businesses pursue climate action while holding onto, or even gaining, industrial capacity and economic security, regardless of how global scenarios play out?

Amid this widening fragmentation, a new, successful model for advancing the fight against climate change is likely to be based on coopetition—collaboration among competitors with the goal of outcomes that benefit all. Coopetition provides a roadmap for businesses and policymakers to thread the needle of net zero’s tightening conundrum. While countries increasingly aim to capture the benefits of green growth domestically, fast and effective reduction of carbon emissions requires a synchronized global effort, supported by international collaboration and a strong global trading system.

The Shifting Geopolitics of Climate

BCG has developed four potential geopolitical climate scenarios for the next decade. They vary widely in terms of outcome:

- Greater global collaboration occurs as countries work together to take effective action and limit global temperature increases. Open global trade, backed by an international system of carbon pricing, ensures that decarbonization happens effectively and equitably.

- The proliferation of regional conflicts exacerbates chronic uncertainty, which limits the ability of countries and businesses to invest and plan. Supply chain disruptions lead to a greater focus on economic security, raising the cost of decarbonization. Global institutions struggle for relevance, and worldwide cooperation becomes increasingly challenging. While some progress is made toward net zero, it is fragmented and limited.

- The world moves toward more certain, but more divided, rivalries as it splits into competing blocs. Some regions make progress in achieving net-zero goals, while others prioritize domestic industries over climate collaboration. Trade barriers slow the exchange of green technology and resources (such as rare-earth metals), driving up costs and limiting the ability to scale emerging solutions. Being able to move beyond multipolar solutions to global ones depends on the willingness of blocs to recognize the urgency of the issue, overcome their differences, and cooperate on climate action.

- The world moves toward a point of no return on climate damage. Escalating global conflicts bring climate action to a halt in the face of national economic security concerns and military conflicts. Fossil fuels dominate, and global warming accelerates. Resource scarcity leads to intensified conflict, and cooperation on green technologies or sustainable practices disappears.

While all these scenarios are plausible, current events point to increasing multipolar rivalry, with different blocs moving toward net zero at different speeds because of economic disparities and varying political agendas. We can expect increasing overlap among trade, industrial security, and climate policy, particularly in developed economies. Critical minerals will become geopolitical levers, and countries with high concentrations of essential materials (such as rare-earth elements) will have greater ability to exert influence over global green supply chains. Nations will prioritize resource nationalism and national security as they seek to prevent dependence on adversarial powers for critical minerals and to stop strategic industries from being hollowed out or ceded to geopolitical rivals.

Three Climate-Specific Impacts

As countries and companies grapple with these shifts and tensions, three climate-specific consequences are likely to shape the course of actions toward net zero going forward.

More Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms

Increased competition in green industrial policies and a rising use of trade defense measures are likely. Governments will want to nurture domestic players to secure leadership in the green economy and to protect these companies from green imports as other countries develop local capabilities.

Markets that are considering or already imposing carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAMs), including the EU, UK, Canada, US, Australia, and Japan, account for 54% of world GDP and 66% of global trade. These “green tariffs” are levied on imports based on the volume of greenhouse gas (GHG) emitted in producing these goods (although calculating the precise level of emissions can be tricky). Since levies relate to the amount of carbon produced, not value, they can vary widely for the same product. For example, based on European Commission estimates of carbon intensity, BCG calculates that the average European CBAM payable per tonne of steel imported from India could be as much as triple that levied on US products by 2034.

Countries can use CBAMs for different ends, such as limiting emissions, leveling the emissions playing field with other nations, and protecting domestic industries. The EU (23% of world trade) has imposed a CBAM on carbon-intensive products (such as iron, steel, cement, and fertilizers) and is currently studying whether to extend it further. The UK will introduce a similar scheme to the EU’s in 2027. Australia and Canada are examining policy options in this area, while multiple legislative proposals—three of which would result in a carbon-based import levy—have been introduced into the US Congress.

Rise of Trade Defense Measures

Under pressure to protect domestic industries and jobs, a rising number of countries are implementing trade defense measures, such as additional tariffs on green products, and erecting new trade barriers. Progress under the WTO’s Environmental Goods Agreement—initiated a decade ago to eliminate tariffs on a wide range of environmental products, such as wind turbines, solar panels, water treatment systems, and air pollution control devices—has stalled, with only 46 WTO members participating. Many countries do not agree on the lists of goods to be covered because of varying national interests and priorities.

These trends are accelerating. For example, only eight countries representing 1.2% of total trade in electric vehicles (EVs) imposed trade defense measures on EVs in 2019. Today, 41 countries representing 40% of total EV trade have instituted such measures. Defense measures are not confined to developed markets—countries such as India and Turkey are considering or imposing tariffs on EV imports while simultaneously incentivizing domestic production.

Increasing Complexity in National Approaches to Green Policy

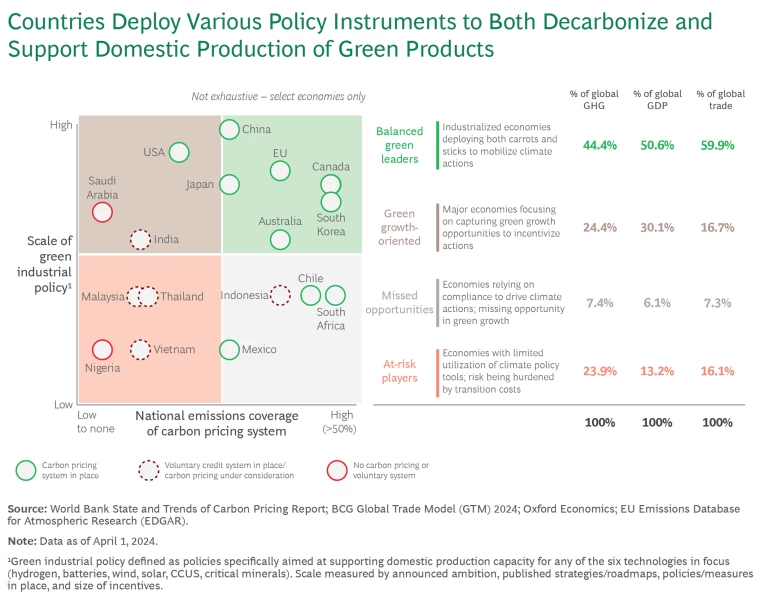

Countries are applying a widening array of green policy initiatives, including both “sticks,” such as carbon pricing, and “carrots,” such as tax credits or other incentives. (See exhibit.) Compliance-based carbon pricing schemes are proliferating, in part as a response to the rising number of CBAMs, instilling greater complexity into global trade. According to the World Bank, there are 75 carbon pricing schemes today, an increase of around 25% over the last decade, covering 24% of global GHG emissions. At the same time, countries are deploying green industrial policies to incentivize domestic climate action and the innovation of new technologies. They also hope to create new jobs in green growth opportunities and generate more competition across industries. The result is a complex patchwork of policies and practices that adds to overall climate policy fragmentation.

Finding Agreement Among Differences

International competition and collaboration both have roles to play in the global energy transition . The risk, in an increasingly multipolar world, is that we focus too much on competition and too little on collaboration. In fact, it will be coopetition that provides advantages to countries while accelerating climate progress. Here are five recommendations for government and business leaders to maintain progress toward net zero in any scenario. The first two are immediate priorities. Three more relate to the longer-term strategic challenges that need to be bridged.

Set common standards.

Progress requires measurement, which to be useful must be based on common standards. While the international community has made good progress on setting carbon accounting standards for companies (such as the work done by International Financial Reporting Standards) there has been less progress toward agreement on carbon accounting for products. Understanding product-level emissions is critical for the administration of CBAMs, but this will become particularly challenging if different jurisdictions develop their own rules. For example, the current UK and EU schemes cover slightly different sets of products and emissions scopes and are likely to use different default emissions values. To ensure credibility and use of the system, the standard setting process should be open, transparent, and equitable, building on the work of the International Organization for Standardization.

Focus on outcomes.

Many jurisdictions today set rules for how to decarbonize rather than hard targets for lowering emissions on the way to net zero. They then debate who has the best system or process, each insisting that their domestic arrangements are the most effective. In a more fractured world, reaching global consensus on any issue such as carbon pricing will become more challenging. Leaders should consider targeting equivalent outcomes, rather than harmonizing rules, ensuring that all efforts are fairly recognized and avoiding double regulation and taxation. A good place to start is factoring in domestic carbon pricing systems when introducing CBAMs together with mutual recognition of independent verification.

Take a balanced policy approach.

For countries to achieve net zero emissions, leaders have been focused on the difficult task of balancing the energy trilemma : energy security, energy access, and sustainability. With these competing priorities, building domestic political support can become the default. But a balanced approach is still possible. Legislative actions in recent years in countries such as the US show that policymakers can move the needle on climate goals. Leaders should consider the trade-offs when setting goals and making decisions on matters such as green industrial policy or trade defense measures.

Push for global inclusivity.

Emerging markets have a key role to play in the energy transition, both as important players in green value chains and as significant sources of GHG emissions. All leaders should consider how best to include their countries in global initiatives while supporting domestic efforts through such measures as development financing, R&D support, and technical assistance to ensure emerging markets can play their full part within green value chains. While it remains significantly underfunded, the EU’s Global Gateway initiative—which coordinates investment and support for countries involved in the extraction and processing of critical raw materials—is one example of this kind of initiative.

Maintain carbon competitiveness.

The shifting geopolitical and climate-change landscape has significant implications for business as well as government leaders. As carbon pricing and regulation spreads, it is more important than ever for companies and governments to plan ahead to ensure they remain not just cost competitive but carbon competitive. Companies need to be nimble and resilient in the face of the “geopoliticization,” and especially the polarization, of climate. In particular, they need to be prepared for intensifying competition between blocs, which could affect their ability to sell products in long-standing markets because of new barriers to manufacturing locations or component parts. Business leaders should assess their companies’ exposure against a range of regulatory scenarios.

In addition to the five recommendations above, companies also need to be much more strategic and pragmatic about their net-zero pledges, which they will have to achieve under evolving, and quite possibly adverse, scenarios. Businesses should develop a playbook that includes both no-regret moves and big bets—and be ready to respond appropriately to geopolitical developments to ensure they remain carbon-competitive. For example, EU automotive OEMs need to consider their exposure to rising carbon costs on essential inputs such as steel, while non-EU producers must evaluate how their competitiveness might change once their products become subject to CBAMs in key export markets.

Competing priorities and multi-dimensional relationships are facts of life in government and in business. The global energy transition amidst international fragmentation adds new priorities and complexity to the mix. Collaboration among countries remains essential if they are to reach their net zero goals. Companies need to build geopolitical climate muscle to better identify, assess, monitor, and mitigate shifts in the net zero landscape. Approaches based in the principles of coopetition can be an effective way forward.