Capital is no longer cheap. And if today’s higher rates are here to stay, business leaders will need to relearn old ways of thinking about capital allocation. After all, many of today’s CEOs and CFOs grew up—and many of today’s corporate portfolios were built—in an environment of exceptionally low interest rates.

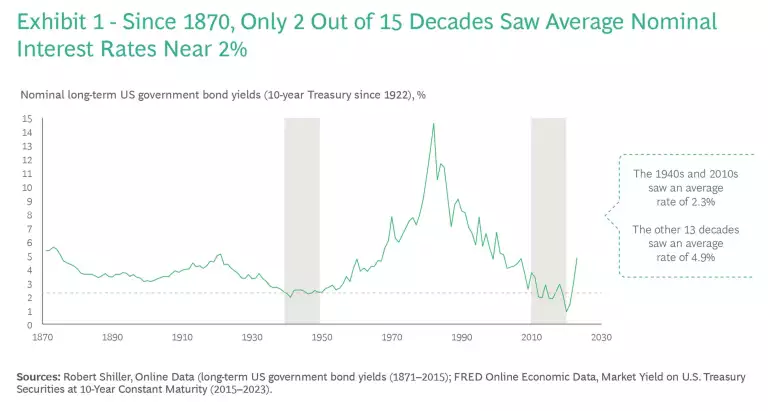

A look at the last 150 years of economic history shows that our recent low-rate environment was atypical. Since the 2007–2008 financial crisis and until recently, nominal long-term interest rates were about 2%. But we have seen sustained rates at such a low level only once before in US history: to support the wartime economy of the 1940s. (See Exhibit 1.) Over the rest of the period, nominal interest rates averaged 4.9%—and the average remains above 4%, even if you exclude the period between 1975 through 1986, when the Federal Reserve pushed rates up substantially to combat entrenched expectations of inflation.

In a higher-rate environment, corporate hobbies that have not fulfilled their initial promise are suddenly expensive. And companies without a thoughtful corporate portfolio strategy will fall short of their full value creation potential as they continue throwing cash after marginal positions in pursuit of growth while underinvesting in their long-term winners. It’s therefore essential to know which parts of your business portfolio are creating value and which are destroying it, and to reallocate resources from marginal positions to winning ones.

With Higher Rates, the Marginal Competitor Becomes…Marginal

Any stable, competitive system comprises a leader, followers, and marginal competitors. The leader and followers have strong and sustainable economics and generate cash returns in excess of their investments. Typically, in a stable sector with low regulatory intervention, leaders and followers are relatively few .

By contrast, marginal competitors have less advantaged economics, and they borrow to invest. While they may show an EBITDA profit, they typically generate returns above the cost of capital only in boom times, when their capacity and products are welcomed because the sector’s leader and followers are sold out.

The era of declining and ultralow rates was kind to marginal competitors. They could finance investments easily as low rates decreased both return requirements and financing costs. All that was needed was a bit of incremental volume, and massive fiscal stimulus was fueling extra demand and growth. In such an environment, it became easier for management to convince itself to add marginal positions to the portfolio, particularly if those positions offered growth prospects that the stock market might value highly.

But with higher rates, marginal competitors will lose their luster. Slower growth will result in customers shifting their business back to leaders and followers. Increased financing costs will weigh on cash profitability. And the market will no longer blindly reward growth prospects in corporate valuations. The bill is coming due for the marginal competitor.

The Imperative for Portfolio Discipline

Are there marginal competitors in your portfolio of businesses? Based on our experience, the answer is very likely “yes.” In fact, they’re hiding in plain sight.

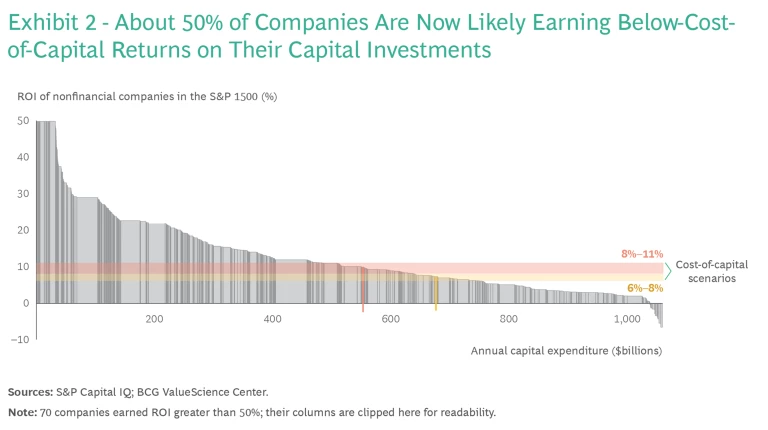

A look at the $1 trillion of annual capital investment by the nonfinancial companies in the S&P 1500 makes the point. Each column in the bar chart in Exhibit 2 represents a company’s most recently reported return on investment. At a weighted-average cost of capital of 8% to 11%—a reasonable estimate for many companies in the current interest rate environment—about half the companies, on average, are earning below-cost-of-capital returns. The picture will only worsen should rates rise higher.

Given the risk that marginal businesses pose to your future valuation, it’s essential to assess the competitive position and cash consumption of each element in your portfolio of businesses dispassionately—and to make hard choices. The moment heralds a revival of the classic discipline of

portfolio management

.

A Three-Part Action Agenda for Leaders

Expensive cash calls for strategic clarity and decisive action. In our experience, getting there requires three steps.

De-average your portfolio’s current performance. It’s critical to start with a granular, creative disaggregation of your business. Too often, organizations combine activities—for example, looking at manufacturing and service operations together, or grouping country operations at a regional level—that are better looked at independently from a return-on-capital perspective. The objective is to recluster your operations and capital allocation into a set of natural strategic segments, each with a coherent customer set, competitor set, and basis of competition, in order to gain a deeper understanding of each element’s strategic position.

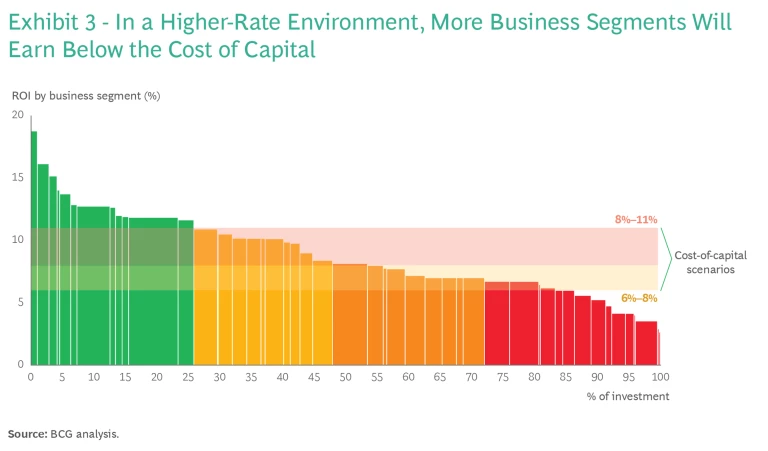

Leaders are typically surprised by the results. Exhibit 3 is an example of what such a disaggregation might reveal. It shows segment performance in descending order of return on investment. At the baseline cost of capital, about one-third of segments (shown in red) are destroying value. It also powerfully illustrates how higher rates will move many currently low- or no-return segments into the marginal category. In our experience with clients, we typically find that the majority of economic value is generated by a minority of portfolio segments—and that between one-third and one-half of portfolio segments fail to clear the cost of capital.

The picture looks a lot like Exhibit 2 but feels more personal—and urgent. After all, low-return segments that drain strategic resources (such as capital, management time, and talent) will increasingly impair results, particularly in a higher-rate environment.

Assess the competitive position, medium-term outlook, and performance improvement options for each portfolio element. In order to translate insight into action, it’s critical to develop a sense of the medium-term value creation potential and reinvestment requirements of each business segment. Is the business a leader, a follower, or a marginal competitor? Does it have a sustainable competitive advantage? How attractive is the market it serves—now and in the medium term? What role does it play in the economics of your portfolio?

This assessment should inform clear-headed plans for what’s needed to accelerate the success or improve the performance of each portfolio element. For high-potential units, what level of investment will be required to fulfill their promise? For marginal competitors, what specific turnaround actions and investment will be needed to ensure that the future is different from the past? And for each, are you best positioned to drive success or is there a more logical strategic owner? Sometimes easy fixes emerge; other times, the exercise reveals that given limited market size and slow growth, no feasible turnaround paths exist.

Ruthlessly prioritize resources to winners and thoughtfully reduce focus elsewhere. The final step is to translate these portfolio insights into actual investment commitments. And in our experience, there will be opportunities to refocus financial and human capital toward higher-value activities. Leaders need to undemocratically allocate available capital—for both business investment and M&A—as well as management capacity to their most promising

The higher-rate regime of the past is what drove BCG’s founder, Bruce Henderson, to pioneer the discipline of portfolio strategy in the late 1960s, introducing business leaders to the terms cash cows, stars, question marks, and dogs. Today’s higher rates argue for a return to a more rigorous approach to portfolio and capital allocation decisions. To bet that we will return to the exceptionally low rates of the 2010s is not a bet to be made lightly. It’s a bet against 140 years of history—and in many ways, it’s an unnecessary bet, at least when it comes to capital allocation. After all, a de-averaged, undemocratic approach to portfolio strategy will always deliver stronger value creation, but it’s existentially important at times like today when money isn’t free.