European leaders are determined to gain competitive advantage in global innovation: reinforcing Europe’s technological autonomy, solidifying its role in the green energy transition, and advancing digital transformation . In this context, the European Central Bank (ECB) has proposed a digital euro: a new form of currency with a payment infrastructure that could accelerate and support innovation .

A well-designed digital euro could enhance Europe’s monetary sovereignty, maintain accountability and safety, reduce cost and risk of cross-border transactions, and foster innovation across industry sectors. To drive the adoption of the digital euro, its design needs to prioritize joint value for all stakeholders. The development of a digital currency promises to ultimately enable the eurozone to leapfrog ahead in multiple domains, giving its countries and companies a competitive edge.

The Case for a European Digital Currency

Europe has a highly educated workforce and robust research base but lags behind in capitalizing on its innovative potential. In 2023, only 8 of the world’s 50 most innovative companies were based in Europe. Moreover, Europe has not consistently scaled up its startups, and the gap tends to widen with scale.

A well-designed digital euro could enhance Europe’s monetary sovereignty and foster innovation across industries.

The digital euro can spark a more capable innovation ecosystem across key industries, including energy trading, industrial technology, and retail. By shifting the current parameters of how payments are conducted by offering increased speed, reduced cost, and conditionality of payments, the introduction of the digital euro can burgeon industrial innovation. Central banks are already investing in the requisite financial infrastructure and knowledge. By funding the infrastructure build-up, they are reducing the risk for subsequent investments and, thereby, creating a fertile ground for innovations to blossom. As a result, European companies could leapfrog across early-stage financial and market hurdles and go to scale more quickly.

China, Israel, Singapore, South Korea, Sweden, and the US have shown how to build highly effective innovation ecosystems. It requires a collective effort by government, the finance community, business, and local entrepreneurs. The digital euro can help catalyze this throughout Europe. (See “The Distinctive Features of the Digital Euro.”)

The Distinctive Features of the Digital Euro

Instant Settlement. Digital euro transactions could be finalized instantly, reducing time and costs.

Interoperability. The digital euro can be designed to integrate with other digital currencies and payment systems, as well as distributed-ledger-based finance products like cryptocurrencies. It would make international transactions easier and more rapid.

Offline Functionality. Payments could be conducted without either party being connected to the internet. This would enable transactions when internet access is limited: for example, in remote areas or after natural disasters.

Enhanced Security and Privacy. Advanced features could protect against illicit data capture, fraud, and cyber threats, ensuring transaction privacy and more anonymity than digital payments offer today.

Programmable Transactions. If the ECB endorses this feature, the digital euro could support conditional payments and smart contracts, executed when predefined conditions are met.

This is a unique opportunity for a multilateral CBDC that will benefit a wide group of stakeholders: governments, finance, industry, and society at large.

Fostering a Digital Euro Innovation Ecosystem

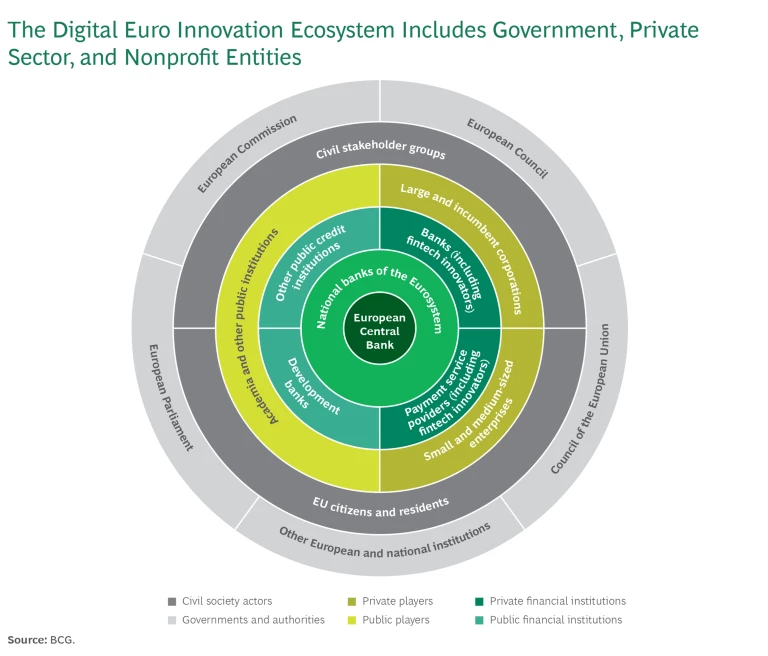

Many countries around the world have investigated central bank digital currencies, but few have successfully introduced them so far. The preparations for implementation have made clear that one key factor that stands to make the digital euro a success is the strong level of political will and capital already in place. However, the strong commitment of public stakeholders is not enough since they are not alone in shaping the digital euro and the innovation ecosystem around it. The exhibit shows the wide array of participants involved.

Government bodies and central banks will provide the legal and regulatory framework and funding for the infrastructure while financial service firms, fintechs, and payment services providers (PSPs) will manage and develop new offerings. Also, nonfinancial industry and SMEs will innovate to both increase efficiency of processes and create new offerings for customers and businesses.

To consumers, these new offerings provide the value that could eventually convince them to adopt the digital euro. Civil society actors (e.g., civil rights associations) and academic institutions could scrutinize the technology and work with private sector actors to develop standards ensuring that consumer and civil rights are protected. Such cooperation would not only contribute to the security of all users but also help with the continuous improvement of the digital euro.

Some existing innovation alliances demonstrate the potential impact of innovation ecosystems on society. For instance, the Swedish government’s digital transformation program promotes R&D in artificial intelligence, 6G, quantum technology, and extended reality. Sweden provides risk capital through Vinnova, its state-owned innovation agency. This, in turn, attracts private capital and talent. Sweden’s approach has placed the country among the top European innovators. With the digital euro, Europe as a whole could become a hub for innovation, leveraging the new and versatile currency, payment, and funding processes as an engine for continuous progress.

What’s Next

Now is the time for key stakeholders to step forward: particularly, private sector players who have, for the most part, so far remained inactive.

Cooperation is needed from many stakeholders:

The European Commission and the European Parliament, together with national governments, could define a vision and mission for the innovation ecosystem. They will decide on the relevant legislation and can ensure the ecosystem is well orchestrated and stakeholders are connected. These entities could also develop innovation-friendly regulation and provide funding to support innovation where required.

The ECB should continue to leverage external knowledge to realize maximum innovative potential. To incorporate a broad range of perspectives, the ECB should continue collaborating with stakeholder representatives such as the Rulebook Development Group and the Digital Euro Market Advisory Group. The current “preparation phase” of digital euro development will last until November 2025. Even in this early stage of the development of the digital euro, the ECB should strive to more strongly incorporate perspectives outside of central banks and financial industry to recommend suitable legal frameworks to lawmakers. If the EU legislative process is completed, the ECB Governing Council will decide whether to move forward with issuance and rollout.

Now is the time for key stakeholders to step forward: particularly, private sector players.

Companies across industries should investigate digital euro use cases now: identifying opportunities, marshalling R&D and investment, and identifying technological and design requirements. For instance, suppliers could decide to have their raw material spendings traced, allowing central certification of ESG criteria. Another example might be using the digital euro as a reward currency for loyalty programs, enabling interoperability among them. By highlighting their ideas to policymakers, proactive companies can now still influence the design and help maximize the potential value-creation of the digital euro. Similarly, financial services firms—banks, PSPs, and credit institutions—could investigate ways to add value, such as integrating the digital euro into existing payment systems.

Politically independent civil society organizations should foster constructive dialogue about the digital euro, addressing risk issues such as data privacy, resilience, cost, and digital sovereignty. Key components will need public scrutiny to establish trust. For example, the ECB might need to demonstrate that offline digital euro exchanges under a certain threshold are as private as the exchange of cash. Identifying the most relevant software pieces to scrutinize, assessing the proof provided by the ECB as well as participating in the debate are key tasks for civil society organizations to fulfill.

With the right vision and design, the digital euro could become a living symbol of Europe’s commitment to innovation—and a blueprint for building trust and cooperation.