As widening geopolitical fissures continue to redefine the world order, a once dormant economic philosophy is on the rise. Economic statecraft is the notion that policies traditionally aimed at promoting economic and industrial development or punishing perceived trade abuses should also reflect foreign policy agendas. The result is an international business landscape that is constantly evolving and has become incredibly complex.

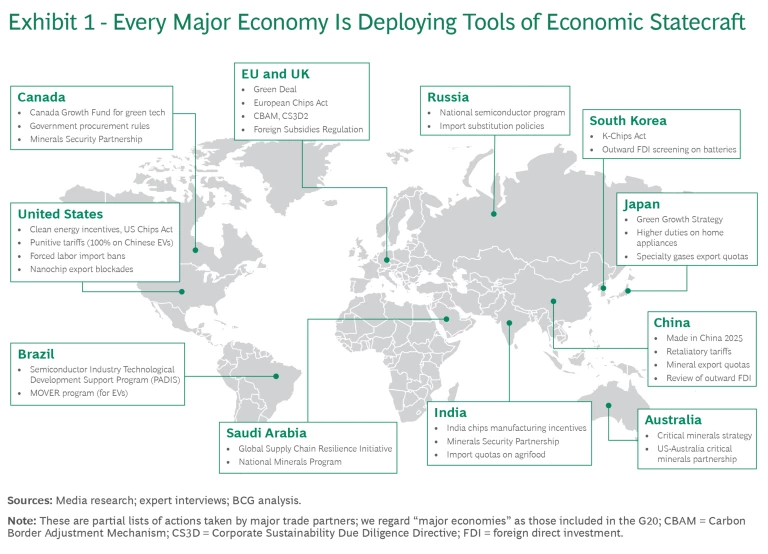

Nations are increasingly acting unilaterally as the relevance of multilateral economic institutions diminishes. They’re negotiating a tapestry of rules and regulations among smaller groups of allies and deploying new policy tools and approaches to advance their interests. Economic sanctions that were traditionally limited in geographic scope are now being applied more broadly, affecting firms around the world. Traditional legal measures for addressing claims of unfair competition in international trade , such as anti-dumping suits, are being supplemented by more extreme measures intended to control access by geopolitical rivals to markets and technologies, such as sanctions, export bans, and discriminatory tariffs. Foreign investment decisions and mergers and acquisitions in sectors that weren’t deemed sensitive a few years ago have become politically loaded. (See Exhibit 1.)

Winning and remaining resilient in this new business environment has become a game of taking advantage of, defending against, or working around new rules and regulations. Yet most companies currently only have the capacity to react to change.

Remaining resilient in this new business environment means working around new rules and regulations. Yet most companies currently only have the capacity to react to change.

Business leaders need to strengthen their

geopolitical

muscle by developing their radar and by monitoring the tools policymakers are using in key markets. Companies can prepare for potential change by reassessing their existing global manufacturing and procurement footprints and then developing contingency plans and hedging strategies for geopolitical risk. They should engage more with politically neutral

emerging markets

, exert greater managerial control over their supply chains, and consider new types of corporate partnerships to mitigate obstacles to foreign investment.

The Forces Driving Economic Statecraft

Economic statecraft has a long history. But it generally fell out of favor during the high tide of globalization. A turning point came in 2013. China, a rising power, launched its Belt and Road Initiative, which leveraged investments in infrastructure projects around the world as part of a strategy to strengthen both its global diplomatic standing and its economic interests. Another key moment was the 2016 presidential election, when both candidates withdrew their support for the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement.

The global free trade movement never regained momentum. Instead, nations have focused on negotiating agreements with more limited sets of partners. Many nations have also embraced industrial policies and other direct interventions in the commercial sector aimed at advancing their own foreign policy objectives.

Five major factors are driving this megatrend:

- Rising Geopolitical Tensions. After decades of relative global peace, armed conflicts have flared in Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Intensifying strategic competition is fueling trade wars, most notably between the US and China, which increasingly are involving their allies and trade partners. Nations are competing more aggressively for control or access to critical natural and technological resources.

- The Resilience Imperative. Companies are reconfiguring global manufacturing and procurement footprints that have relied heavily on a few nations, such as China. They’re diversifying to more locations or relocating production closer to their borders or to nations that pose less geopolitical risk to reduce the chance of costly disruptions and bottlenecks. Governments are also trying make domestic industries more resilient by developing local supply chains in strategic sectors.

- Diminished Faith in Free Trade and Multilateral Institutions. More nations have grown skeptical that free-market forces regulated and mediated by multilateral institutions such as the WTO can guarantee fair competition. They doubt that these entities can ensure a level playing field for developing nations and deliver on a new generation of goals, such as environmental protection, the green transition, economic security, labor rights, and social inclusion.

- A Growing Focus on Emerging Strategic Industries. More nations are viewing key sectors such as renewable energy, electric vehicles, critical minerals, semiconductors, and AI as crucial to economic growth, future job creation, and economic and national security. In some cases, initiatives are being developed in response to other nations’ geopolitical agendas. Vietnam is investing heavily in semiconductor manufacturing, for instance, because it knows the US and Europe are looking for supply alternatives to China.

- Global Geopolitical Realignment. A structural shift in the global order is underway. The G20, a group founded in 1999 that includes the largest industrialized and developing economies, is fraying. The G20’s most advanced economies are strengthening their ties through the G7 and NATO, and some nations such as Japan are building up their militaries. The so-called Western Bloc is exploring collaborations in critical minerals to mitigate supply chain disruptions and ease dependence on certain countries. Developing economies are increasingly working within smaller or regional groups. The ten nations of the Association for Southeast Asian Nations, for instance, are negotiating a Digital Economy Framework Agreement. Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore have also forged a digital economy partnership. Big developing nations are also asserting their voices within the intergovernmental grouping known as BRICS+ .

Next-Generation Economic Statecraft Tools

Although the specific policies countries will pursue varies according to their needs, aspirations, and competitive position, we see four key trends in the tools they’re adopting to attain strategic goals.

Bigger and Broader Direct Intervention in Domestic Industries. Industrial policies are growing in scale, scope, and ambition. Nations are investing massive sums in supportive infrastructure and direct subsidies to manufacturers, for example. They are also using the power of government procurement and national ownership rules to favor domestic industries.

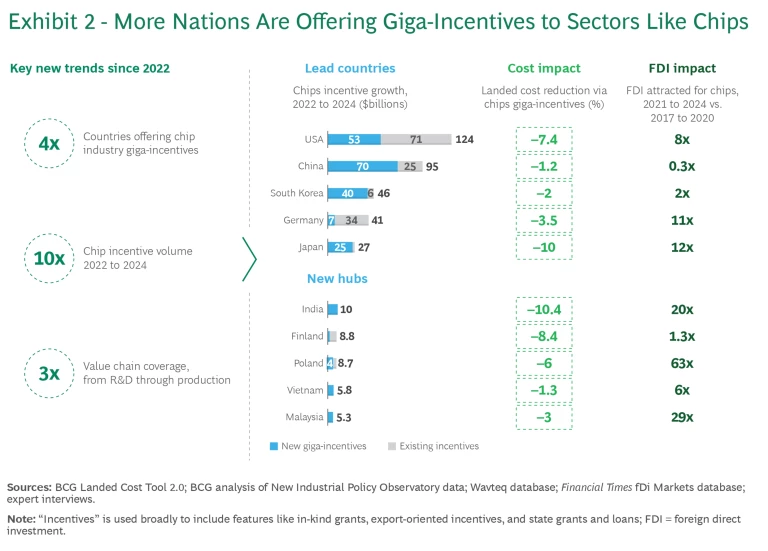

The growing number of what we call “giga-incentives” underscores this new push. Whereas before the COVID-19 pandemic government incentive packages were typically in the range of $1.5 billion to $5 billion, 85% of the packages unveiled since then have been in the $5 billion to $20 billion range, according to BCG analysis. Recent examples include public funding authorized for strategic industries under the European Green Deal, large US incentives to promote investment in semiconductor manufacturing and infrastructure, China’s National Integrated Circuit Plan, and India’s Semiconductor Manufacturing Scheme. (See Exhibit 2.)

These giga-incentive initiatives tend to have several common objectives: to empower companies to produce domestically, to stimulate consumer demand for certain goods and services, to secure a supplier base that can support targeted industries, and to encourage companies to achieve certain standards, such as in environmental sustainability. Another objective is to increase a nation’s global competitiveness in a strategic sector and its attractiveness to foreign investors. Giga-incentives have lowered the landed cost of domestically manufactured chips by anywhere from around 1% to more than 10%. They have also enabled nations to dramatically increase foreign direct investment (FDI) in the chip sectors—by around eight times in the US, more than ten times in Germany and Japan, and more than 60 times in Poland.

Such programs differ on other details. Semiconductor giga-incentives are designed to focus on developing domestic suppliers, for example. In US and European giga-incentive programs for EVs, by contrast, direct incentives are heavily geared toward spurring domestic demand. The breadth of giga-incentive initiatives also varies in terms of how much of the value chain, how many product groups, and how much of the supporting ecosystem are covered. The US Chips Act, for instance, subsidizes both next-generation semiconductors and legacy chips, as well as R&D and workforce training. Similar legislation in the EU more narrowly focuses on nanochip manufacturing.

Funding sources are another key differentiator. The EU prefers to mix money from both established funds and new ones and relies heavily on contributions from member states and the private sector. The US tends to create new funds for strategic industries, mostly supplied by the government.

New Trade Tools to Defend Against Unfair Competition. Increasing global competition and rising geopolitical tensions are leading more countries to abandon traditional long-term approaches to addressing trade disputes in favor of swift, unilateral action. Nations are applying traditional defenses against perceived unfair competition, such as anti-dumping penalties and countervailing duties, to serve foreign policy agendas. Countries filing such actions still must provide evidence that goods were imported at below-market prices or that government subsidies gave producers an unfair advantage—and that these practices injured or threatened domestic industries. Target nations may still appeal to the WTO. But those appeals disappear into a void: the WTO Appellate Body has been unable to function since the end of the last decade. A handful of countries have created alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, but they lack the multilateral enforcement coverage that the WTO’s umbrella once provided.

Recently, the US and other nations have expanded upon traditional trade tools that allow governments to limit imports deemed threatening to national security or to unilaterally impose punitive duties in response to alleged unfair practices. An EU investigation into Chinese government subsidies, for example, recently led to the imposition of tariffs of up to 45% on imported Chinese EVs. Since the EU investigation was first announced, Chinese exports of EVs to Europe have dropped sharply, even though exports rose significantly in markets such as Brazil and South Korea. In May 2024, the US cited Section 301 of the US Trade Act of 1974 to raise tariffs by as much as 25% on Chinese-made lithium-ion EV batteries and certain steel and aluminum products, 50% on semiconductors and photovoltaic cells, and 100% for assembled EVs. For its part, China launched an investigation through the WTO against the US subsidies that it alleges favor domestic products over imports and discriminate against Chinese goods in violation of several trade agreements.

Policymakers are adding new tools to their economic statecraft playbooks that can be expected to figure more frequently into future trade agreements.

Policymakers are adding new tools to their economic statecraft playbooks. Some nations are leveraging environmental, social, and governance criteria to achieve their own economic development agendas. Meanwhile, the EU’s new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism will eventually impose a tax on the carbon-emission footprints of goods and materials imported into the region. And the Facility-Specific Rapid-Response Labor Mechanism, negotiated under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, allows for expedited enforcement of violations of labor rights at individual factories. Such features can be expected to figure more frequently into future trade agreements. Foreign aid has emerged as another valuable tool. China, for instance, has been leveraging loans to developing nations to help secure access to critical materials and contracts for its companies.

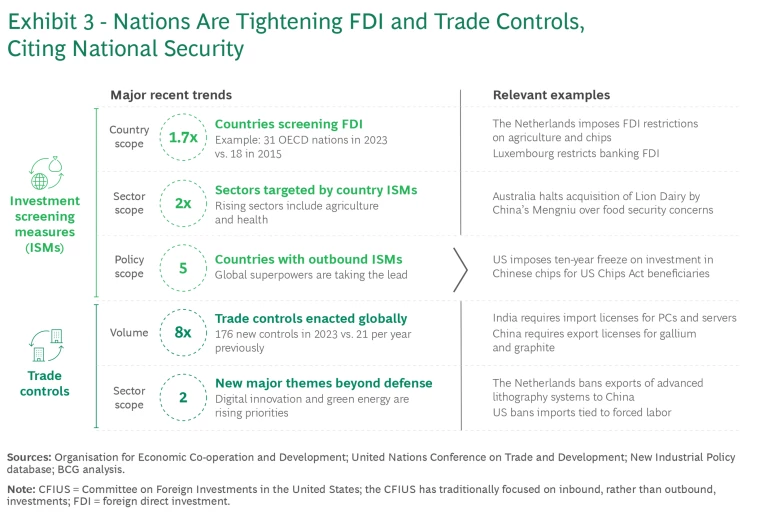

Broader Trade and Investment Restrictions in the Name of National Security. Governments are citing an increased national interest in deploying restrictions on commercial trade and investment—a move traditionally reserved for defense industries. For instance, a country might place restrictions on exports of dual-use technology, such as semiconductor manufacturing equipment and advanced chips used in AI. We’ve also seen growing scrutiny of both inbound and outbound FDI. (See Exhibit 3.)

Screening of inbound FDI isn’t new: the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), an interagency body that reviews the national security implications of inbound investment, was established in 1975. But it has gained new relevance and a broader scope in the past few years, particular amidst growing geopolitical tensions with China. The number of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development nations screening investments, for example, has risen from around a dozen to 31 over the past decade. And the scope has expanded beyond defense, energy, and telecommunications to sectors like financial services, agriculture, and health care.

Screening of outbound FDI, however, will become more prominent as nations seek to protect competitive advantages in high-tech, dual-use sectors. China screens outbound investment deals in sensitive industries, while those exceeding $300 million in nonsensitive sectors require notification. The US is developing a dedicated outbound investment review mechanism, known as “reverse CFIUS.” In June 2024, the US issued new prohibitions and notification requirements on US investments in “countries of concern” involved in sensitive technologies such as semiconductors, quantum computing, and AI. South Korea implemented a mechanism in 2022 to regulate outbound investment in strategically important technologies. In the EU, discussions are underway to finalize such a system.

Sector- and Topic-Specific Plurilateral Partnerships. As multilateralism on trade and investment loses favor, nations are forming international partnerships and regional initiatives to develop specific sectors.

What’s innovative about these new partnerships is their narrow scope, specificity, and speed of reaching agreement. Most legacy pacts covered multiple sectors, involved high-level frameworks on investment and trade, and took a very long time to negotiate and have ratified by national legislatures. Newer, pluralistic agreements are known as “mini deals.” They tend to focus on single sectors or topics, go deeper in spelling out regulations and trade restrictions, and arrive faster at tangible outcomes, such as co-investment roadmaps involving government and strategic private-sector partners. Often, they don’t require ratification from legislatures at all.

Critical minerals are currently the hottest area for bilateral partnerships. Growing demand, geopolitical tensions, and supply chain concerns have prompted nations to forge alliances to secure access to these resources and promote sustainable and responsible sourcing practices. Similar partnerships are starting to emerge around other geopolitically charged commodities and technologies, such as chips, batteries, green tech, and AI.

There are two main archetypes of partnerships. One is the club, such as the Minerals Security Partnership, a collaboration between the US, the EU, the UK, Australia, India, Japan, and other nations that aims to build joint supply chain security in the critical minerals space among member nations. The European Battery Alliance, which has opened to other partners, is another. A second archetype involves critical minerals-backed loans. China, for instance, provides $2 billion in financing to Ghana that is backed by copper and bauxite as collateral. Similar plurilateral partnerships have been established in other sectors.

Four Major Implications for Business

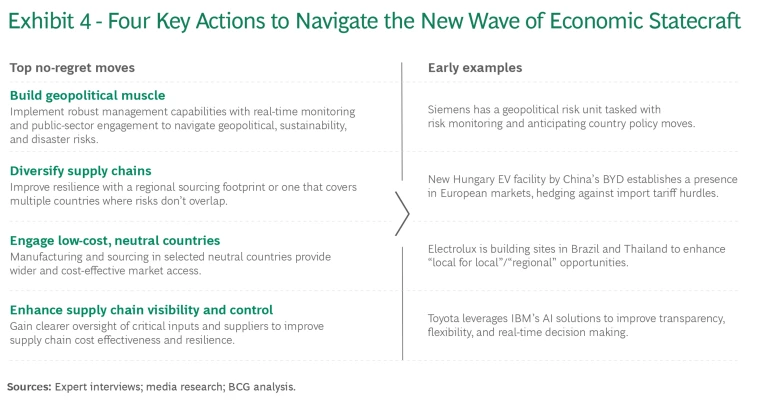

The rise of economic statecraft has profound implications for global businesses. Here are four key actions c-suite executives should consider. (See Exhibit 4.)

- Build geopolitical muscle. Companies must build the capability to identify and anticipate policies driven by economic statecraft that may impact their businesses and assess the likelihood that they will be implemented. They should develop scenarios for how geopolitical events may unfold and their implications. When possible, companies should also engage with the public sector in markets in which they operate to explore innovative investment packages and make policymakers aware of the opportunities they offer. In whichever structure, in-house legal expertise is crucial for navigating countervailing duties and complex, evolving regulations.

- Diversify supply chains. Many company supply chains are concentrated too heavily in one or a small handful of countries. Sourcing goods from several nations whose geopolitical risks don’t overlap can reduce odds that the supplies of critical goods will be disrupted by the same development. Adding some limited redundancy in the supplier networks can also improve resilience. Where feasible, global companies may also consider developing separate supply chains—one catering to Western countries and another to serve markets such as China, as some European automotive OEMs have done. This allows companies to take advantage of local giga-incentives and navigate tariffs and other restrictions.

- Engage with emerging low-cost, neutral countries. Nations such as India, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Mexico are poised to play a crucial role as companies improve their resilience and cost efficiency by diversifying their supply and manufacturing footprints. Such countries also stand to benefit from increased FDI and stronger economic growth.

- Exert greater control over supply chains. Companies should directly manage procurement of their most critical inputs, track their complete supply chains more deeply, and help suppliers and firms that supply them make the right decisions. In the end, the competition today is not only among companies but increasingly among their supply chains.

The rise of economic statecraft makes the global landscape more complex and less predictable. Global companies’ ability to stay abreast of geopolitical developments and navigate an environment of shifting trade policies and industrial incentives is becoming not only critical for keeping supply chains resilient and maintaining access to key markets—it is also emerging as a key source of competitive advantage.