If there were a language for ERP transformation, it would include warnings that look a lot like road signs: “Proceed with caution,” “Speed bumps ahead,” “Blind corner,” and—too often—“Dead end” and “Stop.” By our estimates, more than half of all projects fail to meet their goals. The work is complex and time consuming, with enough twists and turns to stock a Hollywood blockbuster. It’s also priced like a big-budget film, with costs sometimes exceeding 5% of annual revenue.

Yet when ERP transformations hit the mark, they deliver benefits that are worth multiples of the investment. A global chemicals company achieved north of a 2% EBITDA uplift through consistent planning processes and standardized digital processes across all countries and plants. Other businesses have leveraged ERP projects to make data more accessible, slash order fulfilment times, or gain innumerable other advantages.

An additional reason to take the plunge relates to the evolving product landscape. SAP, for instance, is shifting its focus and its support from its ECC platform to S/4HANA. While just one-third of SAP users had started their S/4HANA journeys by 2023, according to Garner, Inc., more organizations will soon be following their lead.

ERP transformation is rarely a solo voyage. It calls for skills and expertise that fall outside most organizations’ core competencies. System integrators (SIs) have those capabilities—and, not surprisingly, we don’t know of any large-scale ERP project that has proceeded without SI support. Organizations invest heavily in these relationships—literally, with 30% to 40% of a project’s budget typically earmarked for SIs—and yet few would claim to have mastered the art of working together.

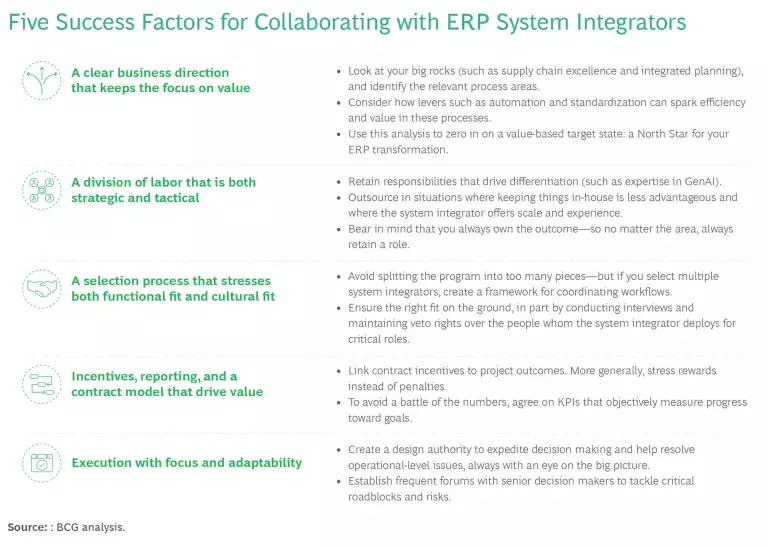

In our experience and from conversations with SIs and business leaders, the most productive relationships share five key elements. (See the exhibit.) Organizations that embrace these success factors collaborate better with their SIs—and spark an ERP transformation that lives up to its billing.

A Clear Business Direction That Keeps the Focus on Value

In our discussions with SIs, one often-mentioned roadblock was the client’s fuzzy view of where the value lay in the ERP transformation. Guidance is often lacking—or all over the place. As one SI put it, “‘Am I turning left or right?’ The client can’t answer.” Companies often direct resources toward capabilities that, in the end, deliver too little value to warrant the investment.

A clear value case serves as a North Star. It keeps people’s focus on the outcomes that matter most. And it establishes guardrails that prevent unproductive detours. The value case links to and shapes every decision, every effort.

So how do you create it? First, consider your big rocks: high-priority goals such as supply chain excellence, integrated planning, and enterprise sustainability. ERP may not be something that everyone in-house uses, but by helping to deliver those goals, it moves the dial for the entire organization. For each rock, first identify relevant process areas. For integrated planning, for instance, these would include finance, sales, manufacturing, and procurement. Then identify levers such as integration, automation, and standardization that can spark efficiency and value.

This analysis lets you zero in on a value-based target state. It also lets you define a clear scope for the program. That’s important because one of the biggest problems in ERP transformation is bloat, which typically occurs when multiple departments try to piggyback their own pet projects onto the main initiative. “If there isn’t a firm business case,” one program lead told us, “clients will ask for more scope [and] changed scope, and the SI can only say yes.”

Working out the target state is a critical step in ERP transformation, and many organizations—depending on their maturity level—seek outside help to accomplish it. This works best when the outside party has no stake in implementing the transformation. The idea is to remove any potential for a conflict of interest. If the SI or software vendor delivering the project also helps set the scope, you may end up with decisions that serve the supplier's interests better than they serve yours.

The dynamic of using one partner to define the target state and another to deliver it highlights a couple of key points. First, you need to ask some important questions before the SI comes on board. What capabilities, skills, and organizational changes will the project require? What is the cost baseline? What software products best align with your ERP vision? A well-defined target state that provides a clear business direction will help reveal the answers.

Second, ERP support isn’t just about SIs. A smart sourcing strategy often involves working with several types of partners. Although this article focuses on SI collaboration, it’s important to understand the different roles of different players. (See the sidebar.)

The Support Ecosystem for ERP Transformation

- Strategic Direction and Oversight. When defining the target state, an organization must understand what good looks like, what it takes to get there, and how realistic the target is. Although many organizations develop this perspective internally, others seek outside viewpoints. In those cases, it’s best to maintain separation between the advisors who help set the firm’s direction and the SIs who implement the supporting technology. Because strategic decisions impact the scope of technology delivery, there’s an inherent conflict of interest when one party tackles both. In the same vein, a third party should handle oversight. An SI shouldn’t be responsible for reviewing its own homework.

- Business Change. If an ERP transformation is to deliver maximum value, organizations must combine technology change with adjustments to their operating model—for example, new roles and new training. Here many organizations look beyond their SI partners for deep domain expertise.

- Technology Delivery. This is the SI’s bread and butter: providing the core skill sets that enable an organization to drive day-to-day delivery of its ERP program. These skill sets include design, development, testing, and deployment capabilities.

- Product Optimization. No one knows a product better than its vendor. Organizations that seek vendor input throughout an ERP project—not just for presales support—ensure that they will configure and use applications to optimal effect. Indeed, many vendors have subject matter experts, in areas such as finance and procurement, who can help check the quality of the ERP under development.

A Division of Labor That Is Both Strategic and Tactical

You’ll need to answer one other key question before the SI comes on board: which roles and responsibilities do you outsource, and which do you retain?

In our experience, getting the mix right starts by taking a strategic, future-focused view. Look at your target state and ask whether certain areas—say, architecture, generative AI, or vendor management—can spark competitive advantage or are crucial to steering the ERP program. If so, always aim to keep the relevant roles in-house.

On the flip side, you may identify other areas, such as testing, where there’s little advantage in keeping everything in-house and where the SI can deliver big benefits such as scale, experience, and best practices. But no matter what an organization outsources, it always owns the outcome—and the risk of getting it wrong. So even in these areas, you should retain a role. For instance, you might leverage the SI for hands-on testers who can set up toolchains and execute the work at scale, but assign in-house test leads to set standards and provide oversight.

Few organizations have sufficient maturity in every role they want to play. Pulse checks are important, but areas that need work can present a dilemma. You don’t want to put the project on hold while you hire and train in-house specialists. On the other hand, reassigning the role to the SI may not be a realistic option. Consider, for example, the program director—typically an internal role. If you don’t yet have the in-house muscle, but you also don’t want the SI making key calls, what can you do? One solution is to bring in a contractor or company with the requisite experience to get you up to speed and in the meantime help you manage the project.

A Selection Process That Stresses Both Functional Fit and Cultural Fit

A major point of failure in ERP projects is poor coordination between organization and SI. And that risk only grows when multiple SIs are involved and one partner’s work relies on another’s work. So it’s important to think—from the outset of the SI selection process—about how you can spark collaboration, facilitate integration, and mitigate risk. Some best practices can help:

- Avoid splitting the program into too many pieces. SIs are not likely to put forward their A teams for bite-size chunks of work. Unless you need multiple niche skills that a single SI cannot provide, or unless your program size is very large, consider sticking with one SI. We have seen even multi-hundred-million-dollar transformation cases do this.

- If you do select multiple SIs, think about how they will interface with each other and what you can do to coordinate workflows. For example, if one SI oversees data migration, ensure that other SIs know how to get a cut of data when they need it—say, for testing an application they’re building.

- Consider the pros and cons of selecting an incumbent for the new work. In many cases, incumbents are better suited for more technical or incremental work than for bolder, transformative projects, where a fresh perspective can be especially valuable. Keep in mind, though, that passing over an incumbent may adversely affect its morale and motivation—and potentially, its performance of any existing work.

- Ensure the right fit on the ground. People within the organization must work constructively and collaboratively with people from the SI. It is important for you to maintain veto rights over whom the SI deploys for critical roles (such as program manager, lead architect, and function lead). To exercise those rights most effectively, conduct interviews before the team lands.

- Instead of issuing a lengthy request for proposal and asking SIs to respond, set up brainstorming workshops to develop a shared understanding of how technology will enable the business. The resulting understanding will have a depth that no document—however detailed—can match.

Incentives, Reporting, and a Contract Model That Drives Value

Like most other sourcing deals, SI contracts tend to follow traditional models such as fixed-fee and time-and-materials. Even so, there’s room to be creative and ensure that both sides are working toward the same outcomes.

Consider the case of a global beverage company. It recognized that realizing its ambitious ERP vision would likely require significant course correction as the project took shape. It also knew that the fixed-fee and time-and-materials models offered different advantages. The time-and-materials model works well when work is uncertain, as it gives the organization more control over the resources that the SI deploys. But the fixed-price model is preferable when the project’s scope is clear, such as when the underlying architecture is stable. To get the best of both worlds, the company chose to follow a time-and-materials model at least until it completed the first wave of deployments. At that point, if the architecture was stable, the contract would shift to a fixed-fee model.

In general, rewards foster value more effectively than penalties do. SIs typically bake penalties into their price, resulting in a price increase without any value addition. A better approach is to use that same money to pay rewards when the SI achieves certain milestones. These may be technical milestones—the decommissioning of a legacy HR system, a new finance system launch, and so on—or business outcomes, such as reaching a certain threshold of employee satisfaction or migrating a specific percentage of products to the new system.

Linking contract incentives to project outcomes can be a powerful way to drive the goals of an ERP transformation. A key goal for a leading energy company was to streamline processes and simplify technology globally. Accordingly, when drafting the contract, the company and SI agreed to an incentive under which the company rewarded the SI each time a module of the core ERP software went live with 80% out-of-the-box functionality. We often see up to a third of a contract’s value linked to such outcomes.

Of course, incentives work as intended only if the parties fully understand them and if there is an objective way to measure progress toward designated milestones. The key is to agree on a measurement framework before execution starts. Such a framework forecloses potentially fractious debate and unproductive battles of the numbers in the midst of implementation.

Execution With Focus and Adaptability

ERP transformation programs must be flexible and adaptable. Project leaders should facilitate and prioritize agile decision making, encourage feedback, and spark responsiveness. To achieve these ends, we recommend establishing a design authority (DA). This cross-functional group—composed of business and IT leads, program leads, chief architects, and in many cases representatives from the SI and even product vendors—arbitrates between teams and ensures that decisions benefit the overall project and not just one particular stakeholder. By championing the big-picture perspective, the DA steers the transformation toward optimal value creation. And by making decisions quickly and decisively—instead of running issues up the chain of command for resolution—the DA speeds execution.

Of course, for critical roadblocks and risks, informed input from senior management is essential. For this reason, we recommend establishing frequent forums with key decision makers early in the transformation. These forums should be action-oriented and should focus on truly executive-level challenges.

This two-pronged approach—with teams on the ground quickly solving operational-level issues and senior management forums tackling critical issues—effectively balances agility and control.

Another key enabler is bidirectional feedback. Constructive advice works best when it runs both ways. Frequent conversations and a channel between the SI and the organization that is open to everyone on the project fosters transparency, timely communication, and course correction.

ERP programs have never been for the faint of heart, and it’s tempting to delay or simply not make the effort. But that leaves value on the table. Although there is no magic formula for getting ERP right, better collaboration with SIs is essential. It’s time to make that a given.

Better collaboration starts with looking at where you are in your ERP project, whether you’re already working with an SI or just starting to plan your journey. Zero in on relevant gaps across the five success factors discussed here, and develop a plan that will bring you closer to best practice. It’s an effort well worth making—because when you work better with your SI, your ERP will work better for you.