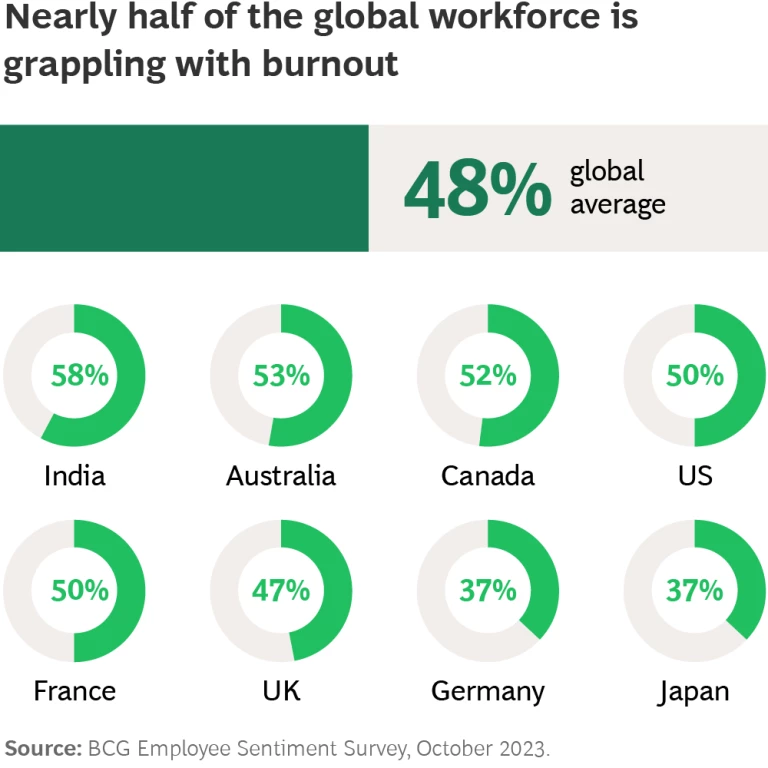

Employers, brace yourselves. Our recent survey of 11,000 desk-based and frontline workers in eight countries found that nearly half are dealing with the symptoms of burnout—a state of exhaustion characterized by disenchantment with one’s job and a sense of inefficiency. Prolonged work-related or personal stress typically triggers burnout, which for some employees heightens the risk of attrition and for others provokes different, equally undesirable outcomes such as a reduction in morale, engagement, and productivity.

But now, employers, take a deep breath. We’ve also uncovered some surprising ways to alleviate feelings of burnout.

That’s because our research has revealed that burnout—which has historically been considered a consequence of long hours, a physically demanding job, or a high-stress environment—is also highly correlated with low feelings of inclusion . Essentially, employees who are more burned out feel less included at work.

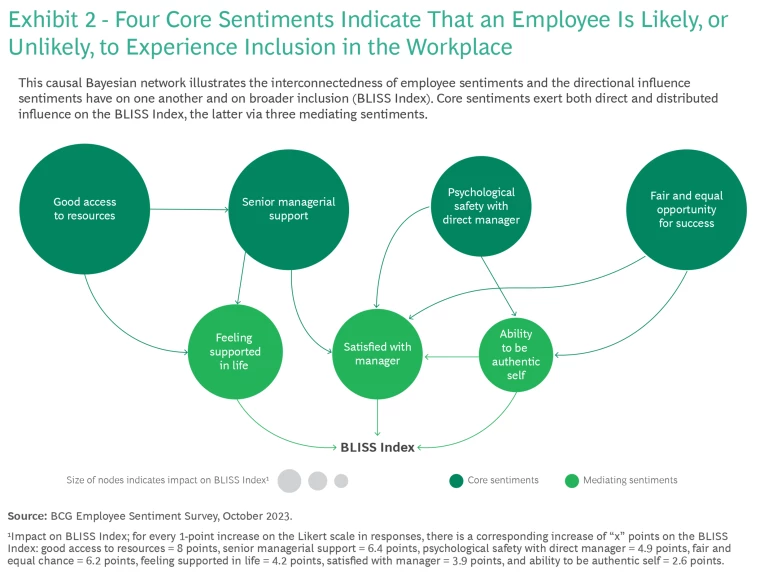

How to address high burnout and low inclusion? Our survey revealed four sentiments that have the greatest impact on employees’ overall sense of inclusion:

- Good access to resources

- Senior managerial support

- Psychological safety with direct manager

- Fair and equal opportunity for success

These signal how much, or how little, people are experiencing inclusion in the workplace. When employees feel that these sentiments are positively addressed in their workplace, they feel more included and less burned out.

About Our Research

The survey captured self-reported data. Likewise, subgroups of respondents were determined on the basis of employee self-identification, rather than legally determined status.

The Importance of Inclusion

Inclusion is central to building and maintaining a successful workforce. Inclusion in the workplace means that employees feel valued, respected, supported, and like they belong. For this research, we quantified inclusion as a score of how inclusive an employee finds the workplace to be, using BCG’s BLISS Index, a statistically rigorous tool that identifies the factors that most strongly influence feelings of inclusion in the workplace.

Our research on the BLISS Index found that employees in more inclusive workplaces have improved happiness, well-being, and motivation, which translates to positive business outcomes, like increased productivity. A 2015 study at the University of Warwick found that happier employees are more productive, for example, and 2019 research from Oxford University’s Saïd Business School corroborated the outcome, reporting that happier employees are 13% more productive. Workers experiencing higher inclusion are also more likely to stay in their jobs, decreasing turnover costs for businesses.

Conversely, less inclusive workplaces see more burnout and more attrition.

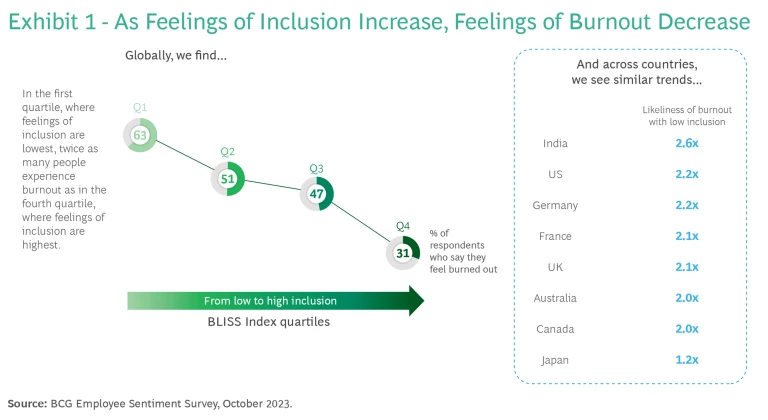

Burnout and inclusion are tightly intertwined across every market we assessed: the likelihood of burnout increases with low inclusion in each market, by 1.2 to 2.6 times. When inclusion increases, from the lowest quartile to the highest, burnout is halved, demonstrating that inclusion should be part of the solution to reducing burnout. (See Exhibit 1.)

And while burnout is prevalent across all employee types, it’s far higher for certain subgroups. Women, members of the LGBTQ+ community, people with disabilities, and deskless workers experienced up to 26% higher burnout. Moreover, these employee groups reported lower inclusion than employees who were in majority groups or were desk-based. Multiple studies have reported that marginalized groups—including women, the LGBTQ+ community, and people with disabilities—experience higher rates of workplace burnout. Marginalized groups often face additional workplace burdens that contribute to feelings of burnout, including increased discrimination, stigmatization, and low representation/survivorship bias.

Feelings of inclusion are shaped by the working environment and conditions, both of which are the focus of companies’ employee value propositions. Often, EVPs are designed to be broadly appealing and applicable—but this approach can overlook the differing realities, identities, and needs across multiple segments of the workforce. For example, companies that offer flexible scheduling might take a one-size-fits-all approach, when in reality different segments of the workforce might require different options. Caregivers, for example, are likely to favor stable flexible schedules to accommodate school or daycare coverage, while workers enrolled in higher education programs might want more dynamic flexible schedules that can be adapted as class schedules change.

While burnout is prevalent across all employee types, it’s far higher for certain subgroups.

To avoid the costs associated with burnout, effectively attract talent, and reap the benefits of a thriving workforce, businesses must rely on employee and business operation data to reimagine their workplaces with inclusion—for all employees—as a central tenet.

Focusing on the Four Key Sentiments

In our survey, four core sentiments emerged as the most important indicators of feelings of inclusion. Companies can focus their initial attention on just these areas and diagnose where they may be falling short in their current efforts to meet employees’ needs. This will reveal where to invest and innovate to improve feelings of inclusion and reduce burnout.

Bayesian network mapping of these sentiments lets employers see how the four core sentiments are connected and how they lead to feelings of inclusion. Focusing on the core sentiments gives leaders a place to start when developing targeted interventions. (See Exhibit 2.) By concentrating on the high-impact upstream sentiments—such as feeling safe when sharing thoughts with a manager and feeling that everyone at the company has a fair and equal chance—leaders can also influence downstream sentiments and inclusion in an efficient way.

We asked participants to respond to the following statements by selecting options that ranged from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

“I have good access to resources to help me be successful.” Survey respondents who indicated they “agree” or “strongly agree” with this statement were referring to resources that enable their productivity and long-term success at work. Some of these resources, such as flexible scheduling, learning and development opportunities, and mentorship programs, exist within core business operations. Others, such as those that help meet challenges related to childcare and transportation logistics, might involve partnerships with providers. And some employer offerings might be less traditional—but equally valuable. For example, providing access to employer-sponsored short-term loans or grants that an employee can access in times of crisis.

Employers should seek to understand the diverse resource needs of their employees and find ways to ensure, where possible, that those needs are met.

“I have a senior supporter at work.” With senior leadership support, employees are better able to navigate and develop their careers. They develop deep connections to their colleagues and management; these relationships are important to feelings of inclusion. There’s an emotional element too—being supported also means feeling valued and respected, both of which are core elements of our definition of inclusion. When employees share this sentiment, they are likely to be more productive and stay with their employer longer.

“I feel comfortable sharing my views with my manager.” In an environment where people feel secure and confident expressing their thoughts and ideas—even disagreeing with their manager—employee development and business innovation are buoyed. Further, previous BCG research has shown that teams whose leaders foster psychological safety show greater motivation and less attrition, especially among members of historically underserved groups. Our earlier research also showed that when employees feel psychologically safe with their manager, their feelings of inclusion improve as well.

“At my company, everyone has a fair and equal chance to succeed regardless of their background or identity.” Fairness and equality foster trust, encourage collaboration, and make employees feel valued. In this environment, they also feel comfortable being their authentic self, without fear of how that may decrease their career potential. Importantly, it’s not just about an environment free of discrimination. It’s about seeing that people who represent a diversity of thought, background, identity, and experience can succeed in the organization and achieve leadership roles. So, when members of marginalized groups do not see themselves reflected in senior leadership, it is hard to believe that the organization is equitable.

Targeting Gaps in Feelings of Inclusion

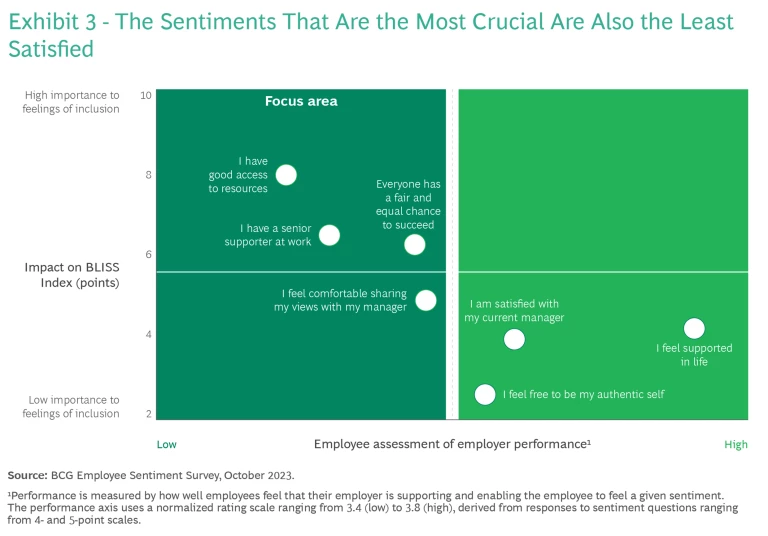

Unfortunately, these most important sentiments are also the ones where survey respondents indicated the lowest levels of satisfaction. (See Exhibit 3.)

These sentiments are positioned nearest to the top left corner of the exhibit, indicating high importance but low employer performance in delivering the necessary support. (Performance is determined by employee assessments of how well their employer is providing for a need.) These results show significant opportunities to improve inclusion.

Delivering improvements in these four areas will, given their importance, have the greatest impact. To do so, employers will have to think creatively about how these sentiments can be addressed for their workforce, including ways that extend beyond the traditional scope of DEI investments. (See “A Spotlight on Innovative Inclusion Programs.”)

A Spotlight on Innovative Inclusion Programs

Here are two examples.

Shiseido is improving access to resources. Shiseido sought to address the needs of employees who are also caregivers. Recognizing that caregiving responsibilities vary, the company designed a portfolio of benefits so that employees could access those that met their particular needs. Among the resources: flexible daily working hours, a shift coverage pool, reduced hours during early-childhood caregiving years, extended family care leave of up to three years, and support for nursing care.

Capital One is providing a fair and equal chance for career development. Capital One is directly addressing the career aspirations of its frontline workforce with a tailored approach to growth and development through its customer-facing associate mobility program, which gives employees access to senior managerial support. They are paired with leaders for direct mentorship and coaching and get six months of training to gain the skills needed for internal transfer roles. Capital One’s portfolio of learning and development initiatives ensures that employees across all role categories have a fair chance at advancing within the company.

How to Increase Feelings of Inclusion

Feeling included means many different things to many different people. It follows that building inclusion can be daunting. But focusing on the four most important sentiments gives employers a clear starting point to ask workers the right questions and focus their efforts to understand the employee experience. Inclusion doesn’t end at recruitment. It requires listening to workers on an ongoing basis and solving for their pain points. It must address both the employee offer and the daily experience of employees through direct management.

Deeply understand your employees and design benefits that cater to their needs. Businesses seek to gain a comprehensive knowledge of their customers. They need to apply the same rigor to understanding their employees. They should know what’s required to keep their workers happy, motivated, and retained. And they must identify where they are falling short. They need to investigate how well they are delivering across the four sentiments—in the opinion of multiple employee groups. Who sees the workplace as a fair environment for advancement, for example, and who does not? Which employees feel supported by current approaches, and which are missing out?

Then, using employee data as a guide, organizations can design resources to provide tailored support to all their employees. These benefits could include onsite or local childcare and adult care services, financial counseling and assistance programs, and increased flexible scheduling options (such as compressed workweeks, staggered hours, and coverage pools).

This doesn’t necessarily mean offering more—and more expensive—benefits to the workforce. It means building an offering with the understanding that one size will not fit all. Employers should invest in understanding who is being left behind by the current offerings and creatively redesign talent and DEI strategies that meet employees where they are.

Foster leaders who understand the value of supportive and enriching environments . The best team leaders don’t just manage their team’s work progress. They coach, engage, encourage collaboration, create productive team environments, and facilitate 360-degree communications. Companies need to develop such leaders, who can then help to improve sentiments about inclusion. Strong managers can show that they value diversity and inclusion by sharing aspects of their own identity, elevating voices and perspectives from underrepresented groups, and taking steps to build relationships among team members of diverse backgrounds. To do so, team leaders should create forums that allow employees to reflect on ways of working. These managers must build a respectful and safe environment for junior team members to share their perspectives and arrange regular touch points between senior leaders and the team.

The behavior of the direct manager is where team members experience leadership daily. It is the primary means of communicating that the organization invests in a fair chance of success for all.

When employees feel included, they believe that they can be successful in the workplace environment and find solutions for the issues that matter most to them.

Part of the employer’s job is to understand the key needs that many members of its workforce share and to find ways to meet those needs, tailoring them as much as possible.

To do this, organizations should regularly seek to understand the employee experience and how effectively company leaders are creating inclusive work environments for all. Such data should guide targeted investments to create a workplace where every employee not just avoids burnout and its consequences but actually thrives.

The authors are grateful to Liliana Diaz, Eileen Donovan, Christopher Gentile, Dennis Konczyk, Jean Lee, Elise Myers, and Katherine Rivet for their contributions to this article.