More money than ever is being directed toward addressing the climate crisis, but financing for the “just” component of the transition is not ramping up at the same rate as for environmentally focused activities. Some organizations are taking steps to ensure that climate initiatives are fair and equitable for the workers, consumers, and communities disproportionately impacted by the climate transition. But many lack clear visibility into the sources of financing available to support the transition’s social component, which is hindering progress.

What this means, unfortunately, is that many organizations sometimes add the term “just” in front of “transition,” with no real meaning behind it. A global BCG survey of more than 350 banking executives found that while 90% of respondents said it is very important to consider the social impact of their bank’s green transition activities, only 31% reported that these considerations often affect their decisions regarding the climate actions they ultimately decide to implement. These findings are typical across nearly all industries. If most climate transition actions are “just” in name only—what some refer to as “social washing”—then the just transition movement will lose credibility.

It is crucial to unlock more capital to ensure the climate transition is not only green but also equitable. Failure to do so risks limited action on this front, entrenching social inequalities. The International Labor Organization estimates that 78 million workers will lose their jobs by 2030 as we shift to the green economy. Consumers will face higher costs. Land rights, livelihoods, and communities will be impacted. So how can more capital be directed to the social components of climate financing?

For the past few years, BCG has collaborated with many global organizations, including the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, the Council for Inclusive Capitalism, Ceres, and the World Economic Forum, as well as many clients, to explore innovative ways to catalyze financing for the social elements of climate transition actions. Companies, investment banks, governments, regulators, standard setters, foundations, and development finance institutions all have a role to play—and in this article we lay out a clear call to action for each of the stakeholders in this ecosystem.

A Capital Framework to Advance Social Equity in the Climate Transition

As organizations seek capital for the climate transition, targets that focus on cutting greenhouse gas emissions should be combined with social targets that aim to support vulnerable communities, provide equitable access to clean energy, create new jobs, and the like. However, the two aren’t often combined, and when they are, the linkage between them is often muddled. (See “Why Is the Just Transition Such a Challenging Topic?”)

Why Is the Just Transition Such a Challenging Topic?

And it’s difficult to calculate the cost of a goal that hasn’t yet been defined. BCG has estimated that achieving net zero will cost $3 trillion to $5 trillion annually—and other organizations have their own estimates. But while incorporating social goals will increase the cost of the green transition, no organization has been able to confidently estimate this additional expense—or the funding needed. With no universally accepted definition of what makes a climate investment just, and no top-down metric for how much the just component will cost, it’s hard to galvanize action.

To further complicate matters, very little data is available on the linkage between social goals and climate progress. Hence, it is impossible to calculate the percentage of social progress that can be driven by the climate transition process. Can the world achieve only a tiny percentage of its social goals, say 1%, through climate action? Or is it closer to 20%? Without knowing the true social impact of these efforts, catalyzing action can be difficult.

In addition, many stakeholders are looking for a standard set of targets, but the social goals that are appropriate for organizations to address will differ greatly by sector, geography, and context. It’s not possible (or even desirable) to create a single, universally applicable set of metrics for social issues. For example, in our work with the World Economic Forum we created archetypes that highlight country-specific just transition challenges. Similarly, in our work with AVPN we identified challenges related to the energy transition in the Asia-Pacific region. A top-down set of just transition principles guiding prioritization of a range of social topics that can be adapted to specific circumstances will help organizations focus their efforts.

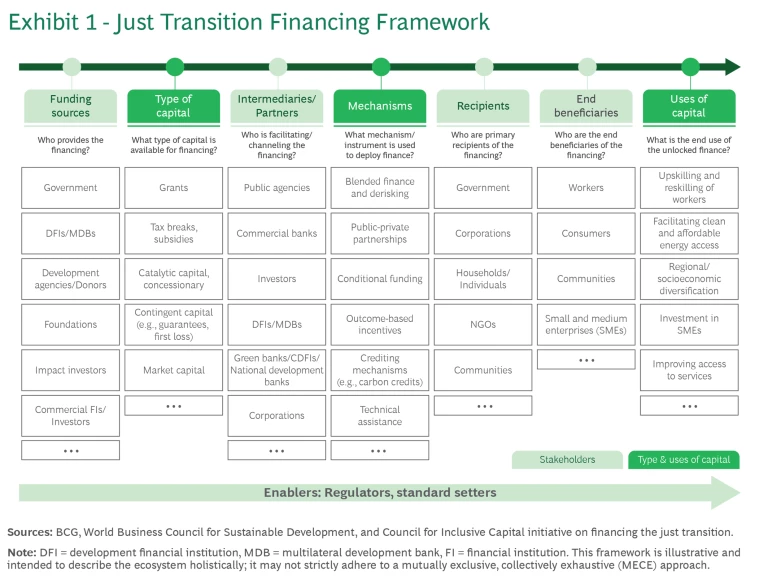

To create more transparency around options for financing the just transition, BCG in partnership with the World Business Council for Sustainable Development and the Council for Inclusive Capitalism is introducing a framework that captures a range of mechanisms and pathways for directing capital to the social component. Decision makers can use this framework to plan and execute funding strategies that ensure climate transitions are socially equitable, people-centered, and sustainable. It also helps organizations spot opportunities and gaps in financing, leading to more efficient capital allocation toward underserved areas. (See Exhibit 1.)

For corporations, the framework highlights different pools and types of capital that can be leveraged for financing the social component and directing capital toward beneficiaries. For banks and intermediaries, it can help identify instruments that embed the just component into their products. For catalytic capital providers, like foundations, it highlights the ways capital can be used to align with social impact goals and support systemic change. The framework also draws attention to the potential of blended finance in bringing together multiple players across the ecosystem. (See “Deploying Blended Finance to Fund Social-Climate Actions.”)

Deploying Blended Finance to Fund Social-Climate Actions

Blended finance is a promising way to incentivize private-sector investment and achieve social and environmental objectives. Capital from public and philanthropic sources is invested alongside private capital, with the former serving as a catalyst for lowering risks, costs, and achieving development objectives. Blended finance is a particularly relevant mechanism for financing the just transition.

Illustrating What Good Can Look Like

A small number of organizations are starting to integrate social goals and outcomes into their climate initiatives. To illustrate how this has been done and share some of the innovative pathways through which capital can flow to fulfill social KPIs, we offer two case studies: the AGRI3 Fund supporting sustainable agriculture in developing economies and the Scottish National Investment Bank financing renewable energy training programs.

AGRI3 Fund

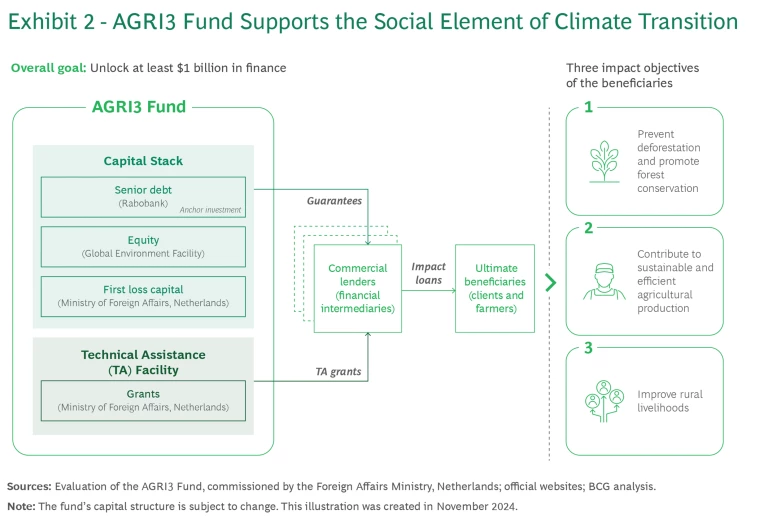

Using blended finance, the AGRI3 Fund aims to mobilize $1 billion in public and private capital by providing credit enhancement and technical assistance to investment projects and businesses that promote sustainable agriculture, protect and restore forests, and support rural livelihoods. For a project to be eligible for AGRI3 support, it must include a social component supporting residents of rural areas through improved income and employment opportunities.

The fund offers various forms of risk participation to financial institutions lending to the emerging economies and $5 million in technical assistance to farmers. It also includes specific social KPIs, including number of farmer trainings, increase in median household income, and number of female beneficiaries.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Netherlands has provided technical assistance grants through farmer trainings to support investments and enhance impact. The technical assistance is offered to farmers and beneficiaries directly or indirectly through execution partners. (See Exhibit 2.)

As Deniz Harut, CEO of the AGRI3 Fund, explains, “The social component of this program was quite important to all our stakeholders. The technical assistance grants enabled us to demonstrate that we could achieve the social benefits, making this more attractive in a way that makes the fund commercially viable while ensuring a just transition.” The fund has made tangible progress toward its impact objectives—and may broaden its scope to support not only rural livelihoods but other social goals, such as food security and nutrition.

Scottish National Investment Bank

Aurora Energy Services, a Scotland-based company with expertise in the energy sector, is supporting the transition from oil and gas to renewable energy. To do this more equitably, they are providing safety training, accreditation, and advanced technical skills courses to energy industry employees. In 2025–2026, they will train up to 2,000 oil and gas workers each year in rural Scotland to prepare them for careers in renewables.

Aurora received a loan of £20 million from the Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB), consisting of £10 million in capital from the Scotland Just Transition Fund and £10 million from the bank. The agreement specifies that Aurora Energy Services will transition from oil and gas to renewables at a specific pace. If they speed up their transition, then the interest rate on the loan becomes more favorable. If the transition is slower than agreed, the interest rate will be higher. In addition to interest rates linked to Aurora’s rate of change, several other KPIs are required. These include the number of permanent employees employed in a just transition role, the number of apprentices and interns engaged in a just transition role, and total revenue generated from renewables activities (compared to oil and gas). Loans from institutions like SNIB enable corporations to get much-needed long-term funding that may otherwise be deemed risky by traditional investors.

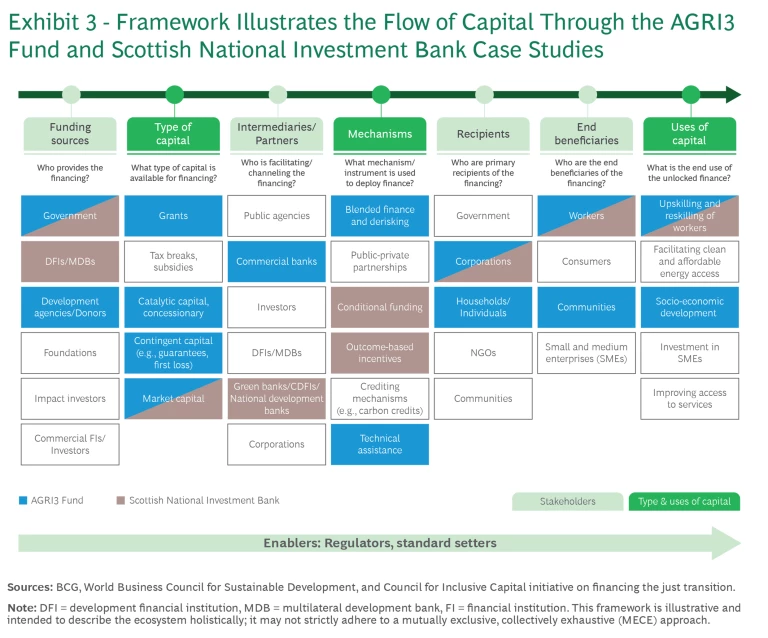

The AGRI3 Fund and Scottish National Investment Bank case studies highlight critical elements that should be part of any just transition approach: 1) a clear strategy that is explicit about the ways climate financing will be used to support groups that are disproportionately affected by the climate transition, and 2) explicit metrics to track progress toward these goals.

Using our framework, we have illustrated the flow of capital in these two case studies. (See Exhibit 3.)

Actions that Ecosystem Players Can Take

To ensure that the climate transition is truly just, significantly more capital must be directed toward social equity outcomes. There is no time to waste; the human and community impacts of climate change are occurring today and will only increase without concerted efforts. We have outlined high-priority actions that stakeholders should pursue now.

Corporations

As direct participants in capital markets, corporations that are raising money for their own climate transition must lead by example to target specific social outcomes and integrate social KPIs into their net zero plans. Companies can issue green bonds or sustainability-linked loans that include social outcomes, such as workforce reskilling and community development. By incorporating these into the loan or bond, companies will ensure that their transition to a low-carbon economy is both sustainable and inclusive. Corporations also need to incorporate their social targets and principles into their transition plans—as Aurora Energy has done —and make this information publicly available to investors and shareholders.

Banks

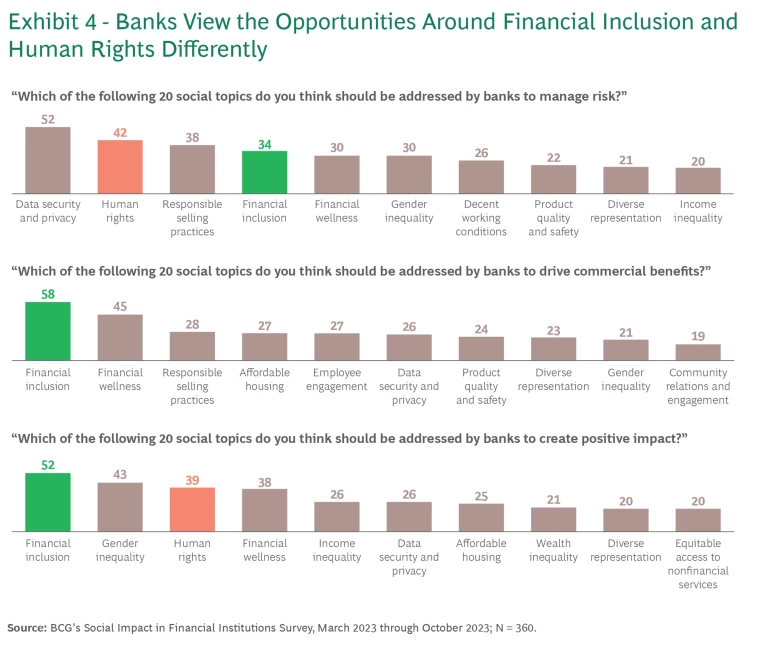

As financial intermediaries, banks have a major opportunity to integrate social considerations into many parts of their business. In 2023, BCG conducted an in-depth study on the role banks can play in an equitable climate transition. Based on this research, we recommend that banks identify ways for corporations, governments, and multilateral institutions to integrate social factors into their green bonds and other sustainability-focused projects, which will make these instruments more attractive to certain types of investors. They should also build social factors into the assessment frameworks that they use to evaluate clients’ climate transition plans as well as potential human rights issues in their value chains. Organizations tend to think of the just transition as a risk-and-impact topic—but it’s also a business opportunity. In our 2023 survey, banks viewed human rights as primarily a risk mitigation and social impact opportunity, while financial inclusion was seen more as a business opportunity. (See Exhibit 4.)

For example, BNP Paribas has created a just transition initiative to identify potential long-term business opportunities. One of their initiatives is a “rent now, buy later” program that enables low-income people to secure a 20% down payment on an energy efficient home after having rented the home for five years. The bank also offers inclusive and sustainability-linked financing loans to microfinance players, local small banks, and companies who wish to steadily increase inclusion and biodiversity.

Investors

Institutional investors, particularly in public markets and asset management, can support the just transition in multiple ways. They should refine their investment criteria to exclude from a climate fund any companies with evidence of child labor or other human rights issues in the supply chain. At the same time, they could create “best in class” funds that only include companies that have explicitly committed to just transition principles. Public market investors should actively engage with companies and encourage them to focus on the social impact of the green transition. For example, HSBC Asset Management includes just transition considerations when analyzing company transition plans. This may include specific metrics or objectives related to employee training and development, green job creation, safeguarding workers’ rights, support to affected communities, and social dialogue, to name a few.

Governments

Governments have the power to shape the financial landscape in ways that can accelerate social impact. When governments offer tax incentives, grants, and subsidies for projects that support climate transition, they should include specific social equity targets as part of the terms for accessing these funds. A good example is the US Environmental Protection Agency’s $6 billion Clean Communities Investment Accelerator (CCIA) program, which enables community lenders to provide financial assistance to deploy distributed energy, net-zero buildings, and zero-emissions transportation projects where they are needed most. All of the capital available through the CCIA is dedicated to supporting low-income and disadvantaged communities. Programs like these will ensure that climate strategies also address social impact.

Regulators and supervisory authorities

Currently, very few regulations take into account social factors in climate actions. Even in the EU, which is considered a leader in climate regulation, legislation is not explicit enough about the linkage between climate and social targets. For example, the European Bank Authority’s guidelines on the management of environment, social, and governance (ESG) issues refers to social risks, but does not link them to related environmental risks. Similarly, the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive requires organizations to report on a range of social and environmental factors but does not call for examining how the issues are interrelated.

While many longstanding regulations that do link these issues have a low bar for social targets, some newer regulations, such as the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CS3D), are moving in the right direction. The CS3D requires companies to identify and address the adverse human rights and environmental impacts of their actions both inside and outside Europe.

Foundations and other catalytic capital providers

Private foundations that focus on social equity should play a key role in financing the social outcomes of climate projects, particularly in regions and sectors that are currently underserved. They should clearly stipulate that funding is contingent upon supporting the social component of the transition, establishing specific social metrics and KPIs that recipients must meet.

Capital providers should incentivize and derisk private sector investment through blended finance and guarantee mechanisms, ensure that financed projects have a strong focus on social equity, and provide standalone grants to support capacity building, technical assistance, and other social needs. For example, the Kresge Foundation is providing $3.3 million in loan guarantees to accelerate development of solar and battery storage technologies in historically underserved communities in New York City. The loan guarantee can be used to reduce risk, which allows traditional lenders who are generally constrained by credit risks to meet both climate and social goals.

Development finance institutions and multilateral development banks

DFIs and MDBs are best positioned to drive innovation on this topic for several reasons. Their mandates encompass social, environmental, climate, and finance goals, and their shareholders expect them to take risks and seize opportunities in frontier markets. They also have deep knowledge on sustainability and emerging markets , strong global networks, and the capabilities to set standards and manage the complex requirements that come with just transition financing.

To accelerate progress, MDBs and DFIs should continue to leverage their unique position in the ecosystem by developing and publishing frameworks and taxonomies. We are seeing some movement in the right direction. For example, in 2024, the World Bank issued a first-of-its-kind taxonomy identifying 57 economic activities to guide investments that support a just transition in the coal sector. This is an important step forward, and more taxonomies are needed for other sectors affected by the transition. DFIs and MDBs can also use their own taxonomies to be the first to issue “just transition” bonds, similar to the World Bank’s first-ever green bond in 2008 or International Finance Corporation (IFC) support for the first biodiversity bond in the financial sector in 2024.

Standard setters and industry coalitions

As key influencers in the capital markets, ESG standard setters have a unique role in establishing the frameworks and guidelines that define a just transition. Many of these organizations—such as Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), and Net-Zero Banking Alliance—already have prepared strong guidance on climate, but they should also collaborate with the broader ecosystem to retrofit their guidance to include social goals. The UK Transition Plan Taskforce has started to do this. For standard-setting bodies such as the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) that cover all sustainability-related disclosures, including climate and social, they should consider ways to link the subjects. A new organization, the Taskforce on Inequality and Social-related Financial Disclosures (TISFD), is currently developing a global framework for inequality and social-related disclosures.

A contrarian view might propose that it’s more important to solve the climate crisis first and focus on the social repercussions later. But the transition to a low-carbon economy has already led to job losses, land use conflicts, and economic disparities. In the summer of 2024, new EU policies aimed at cutting agricultural emissions stoked farmer protests across several countries that triggered the rollback of ambitious climate targets. Collectively, we have a unique opportunity to create lasting social and climate progress by addressing both challenges together. If members of the climate action and funding ecosystem fail to act now on this challenge, existing inequalities will worsen and the climate transition will be derailed by growing resistance.

To advance the climate agenda in a socially responsible way, collaboration will be essential. Capital markets are already a collaborative ecosystem, with a natural interdependence among participants, but they will need to layer in additional stakeholders, such as ESG standard setters, foundations, DFIs, and other organizations that aren’t as frequently involved in the capital market process. Participants in the financing ecosystem will also need to collaborate closely with impacted populations and communities to ensure that they have a voice in the process—and track program outcomes and performance to ensure they are benefiting from the actions. By providing ample capital and investing in actions that address both the environmental and social aspects of the climate transition, we can build a future that is not only greener but fairer, ensuring that no one is left behind.