For the CEO

For the better part of three decades, CEOs have been operating in an historical anomaly. From 1990 through the late 2010s, economies, cultures, and populations were steadily integrating, propelled by an international order where globalization was chic, supply chains just-in-time, and geopolitical considerations a faint blip on most corporate radars.

No more.

The system shaped by Western-inspired institutions, trade, and security regimes is fraying, with post-Cold War international cooperation giving way to increasingly acrimonious competition. Some believe this signals a return to a bipolar world order in which nations fall in line with one of two superpowers—Cold War 2.0, in other words. That view is far too narrow. If anything, current momentum points toward a multipolar world, where dynamic middle powers assert their influence through multiple blocs, regimes, and regional groupings.

The evolution of BRICS this year from five to ten members is the latest indication that the march toward multipolarity is accelerating. Meanwhile, the velocity of geopolitically driven business disruptions is increasing, from the war in Ukraine to spiraling military confrontations in the Middle East. And with pivotal elections approaching in the US and Europe, the potential for further disruptions is significant.

CEOs don’t have to leave their companies at the mercy of geopolitical events.

A more fragmented world undoubtedly presents businesses with a great deal of uncertainty—and tremendous risks. But CEOs don’t have to leave their companies at the mercy of geopolitical events.

How CEOs Can Build an Effective Geopolitical Capability

Large multinational corporations, as well as those that depend on the free flow of goods and services beyond their borders, need to treat geopolitical risk with the same urgency as digitization, AI, and the climate crisis. They need to pressure-test investment decisions and business plans against possible disruptions by developing capabilities that strengthen geopolitical agility and resilience. If those capabilities are robust, they can even turn geopolitics into a strategic advantage.

Put simply, CEOs need to develop a “geopolitical muscle”—and fast.

The Risks of Merely Reacting to Geopolitical Disruptions

The future hasn’t been this uncertain in decades, and CEOs who approach geopolitical risks reactively rather than proactively do so at their peril. Look no further than Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In the months leading up to the war, the prevailing view among most experts was that the Russian military buildup on the Ukraine border was unlikely to tip into a full-blown crisis. Even so, it was a plausible scenario—and when Russia did in fact invade, many CEOs found themselves and their teams scrambling to ensure the safety of staff, find alternative supply chains for critical commodities, and comply with Western sanctions.

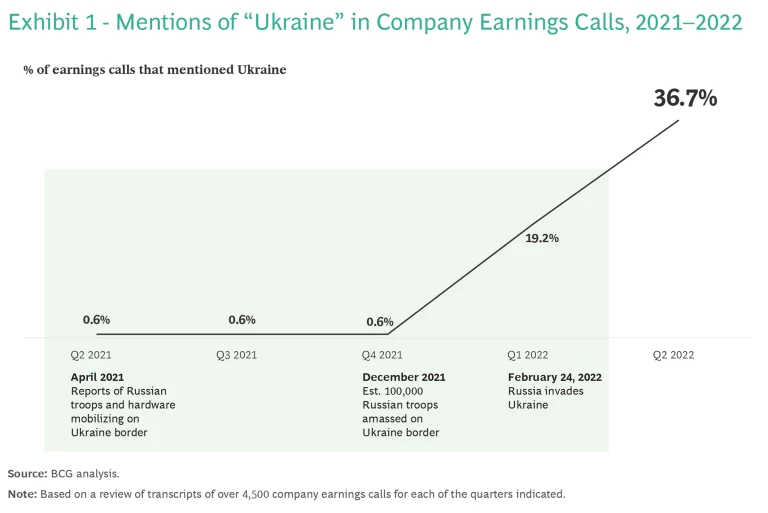

A rough proxy for the prevalence of reactive geopolitical postures among major corporations is the number of mentions “Ukraine” garnered on earnings calls before and after the war started. In the second quarter of 2021, amid news reports of Russian troops and tanks mobilizing on the border, “Ukraine” was mentioned in less than 1% of the more than 4,500 earnings calls analyzed by BCG. That percentage held steady through the fourth quarter of 2021, despite the estimated number of Russian troops soaring past 100,000. By contrast, during the first quarter of 2022, when the war began, Ukraine was mentioned in 19% of earnings calls, climbing to 36% in the following quarter. (See Exhibit 1.)

Hoping for the best is not a strategy. As recent events have driven home, CEOs need to build a capability—an organizational muscle for surveying potential geopolitical disruptions and planning for them, whatever the future brings.

Four Scenarios for the 2030s

Companies that develop a geopolitical muscle are prepared for uncertainty, hardwiring geopolitical considerations into their investment decisions, strategic planning, and operating models. They have a dedicated team focused on geopolitics that utilizes a range of data and analytics to design proactive strategies for mitigating risks and unlocking opportunities. And they build robust systems for monitoring national, regional, and global events for key developments that trigger fast, decisive action when they surface.

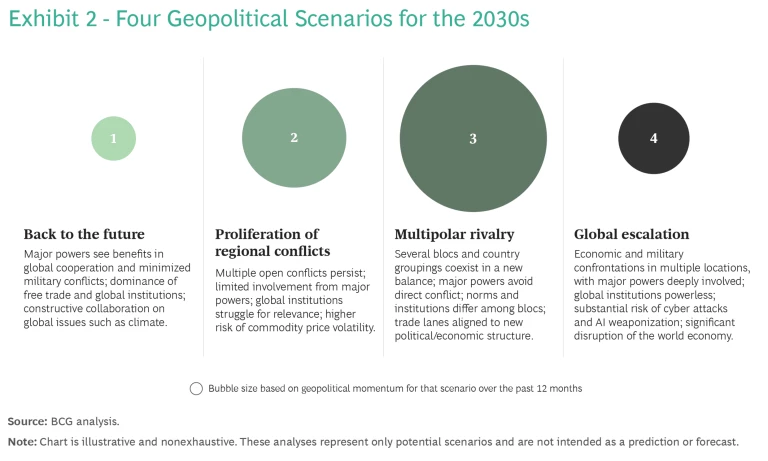

Foundational to this capability is establishing a broad but plausible set of scenarios for how the geopolitical landscape could evolve in the coming years. BCG has developed four such scenarios for exploring where the world might stand in the 2030s. (See Exhibit 2.) That horizon is sufficiently beyond the typical two-to-three-year corporate planning cycle, when most capital spending decisions are already locked in, but not so far in the future that it renders the scenarios purely theoretical.

It’s important to note that these are not meant to be predictive or to suggest a limited set of four outcomes. Rather, they are informed frameworks for gauging where global momentum is heading in the medium term—which in turn can help CEOs and their senior leadership teams gain a sense of grounding in an increasingly unpredictable world.

In scenario one, back to the future, the world’s major powers have once again come to embrace the benefits of greater cross-border cooperation and minimal military conflict. Free trade and multilateral institutions are dominant, enabling constructive collaboration on global issues such as the climate crisis.

Scenario two, proliferation of regional conflicts, is characterized by the spread of focused military conflicts with limited major-power involvement. Global institutions struggle for relevance in this scenario; supply chains are havoc stricken, and there is an increased risk of commodity price volatility.

In scenario three, multipolar rivalry, several blocs and groups of countries coexist in a rebalanced global dynamic where major powers avoid direct conflict, norms and institutions differ among blocs, and trade lanes align to new political and economic structures.

Scenario four, global escalation, is the most chilling. In this scenario, economic and military confrontations take place in multiple locations with deep involvement from major powers. Global institutions are crippled, the risk of cyber attacks and AI weaponization is substantial, and disruptions to the world economy are significant.

Currently, scenario three—multipolar rivalry—has the greatest momentum behind it. But that could change at any point. Amid the war in Gaza, for instance, Iran-backed Houthis have attacked ships in the Red Sea, a vital choke point of global commerce. And with the decades-long shadow conflict between Iran and Israel having escalated to direct military engagement, there could be further consequences for trade and other underlying variables that define the global business environment.

Leadership by Design: Navigate the complexities of today’s leadership and management environment.

What Shapes the Scenarios

The four scenarios described above are shaped by a core set of seven variables. These include geopolitical relations, strength of institutions, trade and supply chains, financial stability, resources and sustainability, technology and productivity, and the policy environment.

One variable that has kept many CEOs awake at night in recent years is trade and supply chains. The snarls created by the COVID-19 pandemic over 2020 and early 2021 alone cost businesses an estimated 6% and 10% of their revenues, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit. The dynamics that will likely shape how trade and supply chains behave going forward include the current state of trading relations between nations, the interconnectedness of supply chains and markets, active support for national reshoring initiatives, and the emergence of regional industrial hubs.

As they gain greater clarity on how goods and services could flow in the 2030s, CEOs and their teams can build buffers against potential fallout on their business operations.

Under scenario one—back to the future—trade would scale new heights as international cooperation becomes fashionable again, and barriers, such as punitive tariffs, recede. The Global South would benefit, with African nations increasing their share of global supply chains, while fewer military conflicts would keep trade-thwarting sanctions in check.

Contrast that with scenario four, global escalation. CEOs would be navigating a world in which global trade plummets and supply chains localize.

As they gain greater clarity on how goods and services could flow in the 2030s, CEOs and their teams can build buffers against potential fallout on their business operations and even zero in on nascent opportunities that less geopolitically savvy companies might miss. And this is just one variable. When all seven are viewed together, CEOs and their teams can start to get a comprehensive view of what macro conditions might be in the 2030s under different scenarios.

Exploring Macro KPIs

Core macro KPIs include GDP growth, inflation, oil prices, global trade , foreign direct investment, the global warming trajectory, international migration, and global inequality.

Take inflation as an example. Under scenario one (back to the future) price pressures revert to lower, prepandemic levels as free trade proliferates and supply chains run smoothly, giving companies greater latitude to pursue the lowest cost production options. Under scenario four (global escalation) inflation is sharply higher than prepandemic levels as trade barriers and conflict upend supply chains and energy markets, dramatically elevating the cost of doing business. Viewed through scenario three (multipolar rivalry) inflation is slightly elevated from prepandemic levels as greater fragmentation introduces more friction into global trade.

Though the differences for inflation and other macro KPIs can seem minor from one scenario to another, each harbors different shocks and shifts that could translate into lost access to key markets or an opening to new ones. Supply chains and core businesses could be jeopardized or turbocharged. Promising new business lines could evaporate or materialize. Access to talented employees could broaden or be restricted.

How CEOs Can Build an Effective Geopolitical Capability

Companies are already thinking about, if not undertaking, measures to shore up business plans and operations against an increasingly fragmenting global business environment. Many are geographically diversifying critical supply chains and manufacturing activities and establishing distinct entities to operate in different blocs. They are also navigating price volatility more nimbly and bolstering risk and cybersecurity capabilities.

Building geopolitical muscle is another key “no-regret move” for CEOs. This is not a task to be outsourced. CEOs need to mount a real capability that lives inside their organization to monitor geopolitical events, strategically plan for critical shifts, and ensure key tools remain up to date. They also need to establish a structure for initiating action quickly when events warrant. Here’s how to do it.

Tailor scenarios and develop signposts. Monitoring emerging shifts in the geopolitical landscape is foundational for establishing a proactive posture. Companies can start by tailoring the four scenarios to their specific industry and context to gain the best-informed perspective of how an individual company’s business operating environment could evolve in the years ahead. Utilizing data and analytics, including from third parties, they can then develop a set of “signposts” that serve as an early warning system that a business-critical change is afoot.

Some signposts can be tuned to obvious developments, such as military movements. Others can be aimed at more subtle ones, such as a policymaker stepping down or a new legislative effort taking shape. Some will be industry-specific, while others may appear to be so but create ripple effects beyond that industry. For example, US legislation aimed at reshoring semiconductor production is highly relevant for chip makers as well as manufacturers that use chips.

Plan your response. Once the signposts are established, companies can draft detailed plans for how to respond when one appears. The insights and expertise of a dedicated geopolitics team will likely determine how effective those plans will be. The optimal size of the team will vary depending on a company’s geopolitical exposure; for many multinationals, it could be a handful or two of dedicated specialists, supported by a dozen or more regional and functional leaders across the organization.

What matters most is the collective expertise the team brings to the table—for example, international relations and global policy, supply chain and risk management, and other relevant disciplines. Companies can also complement their internal expertise with select external experts on certain topics or regions.

Remain vigilant. Signposts and scenarios need to be refreshed at least every two years or after a major incident. While the changes captured may be minor, it is important to ensure these tools remain fit-for-purpose at all times. Signposts also must be monitored vigilantly.

Structure to initiate action quickly. When a signpost appears, companies need to be organized in a way that ensures the information moves swiftly up the chain of command into the hands of senior decision makers. When events are fast and fluid, a CEO may not have the luxury of time when making tough calls, like redesigning a supply chain, selling off a valuable asset, or immediately relocating staff to a less risky environment.

A company’s geopolitical muscle is not built overnight. It takes commitment, dedication, and effort to strengthen and maintain. And it can entail additional costs. But CEOs need to weigh the potentially greater costs should a geopolitical risk become a business-disrupting reality.

The authors wish to thank Alan Iny, Kasey Maggard, and Michael McAdoo for their contributions to this article.