Global companies have spent decades building procurement networks that rely on suppliers around the world that can reliably and efficiently meet their quality standards at the lowest cost and with the speediest delivery. But that traditional approach to supply chain management is predicated on continuing geopolitical stability and a worldwide trade system that facilitates the free movement of goods and capital. These assumptions no longer describe current realities.

Today, companies must navigate an immensely more complex global landscape, one often unsettled by armed conflict, trade wars, sanctions, export controls, and other unexpected developments driven by geopolitics. As a result, CEOs are confronting a tricky balancing act: how to reduce procurement costs at a time of high inflation, while at the same time improving access to key markets and ensuring that their supply chains are resilient in the face of geopolitical risk. The shift toward more regional sourcing footprints reflects one strategy that companies have deployed to address this dilemma.

Striking the right balance between cost, risk mitigation, and market access has proved challenging, however. The result has been stressed global supply chains that remain exposed to trade disruptions, whose financial impact can offset the savings from sourcing strategies based primarily on cost and efficiency. As businesses have experienced repeatedly in the past few years, supply shocks can bring higher-priced materials and shipping expenses, factory stoppages, delivery delays, damage to a brand’s reputation, and lost revenue as companies scramble to find other qualified suppliers of goods and critical components.

A big reason why supply chains are struggling is that risk management has tended to lack the prominence and rigor that companies have long devoted to optimizing cost and efficiency. Therefore, many companies merely react to crises, often after the damage has been done. Nor have many companies adequately prepared for sharp policy shifts, like tariff hikes and curbs on high-tech trade and investment, that can upend long-established supplier relationships.

To be ready for the unexpected, companies should establish a robust system for assessing and monitoring their exposure to geopolitical risk and building supply chain resilience. They should design global sourcing networks based on a holistic, “best value” approach that considers not only the traditional trinity of cost, quality, and on-time delivery, but also supply risk, sustainability, market access, and innovation—all backed by a strong analytic framework for deciding how to make tradeoffs. Companies that are best at managing resilient supply chains can both boost their top line and be well-positioned to gain advantage when competitors are tripped up by the unexpected.

Why Managing Geopolitical Risk Is Crucial

Recent events have underscored the high costs of geopolitical disruption. The war in Ukraine quickly impacted European industries by cutting off the flow of Russian natural gas and industrial components, such as automotive wiring harnesses. Attacks by Houthi militias on cargo ships entering the Red Sea, a crucial marine transit route, led to higher shipping costs and inventory shortages of home appliances and other goods imported into Europe from Asia.

Trade tensions and nationalistic industrial policies have likewise upended the math of global sourcing. Sharp US tariff hikes—and, in some cases, outright bans—on Chinese goods ranging from washing machines to solar panels and lithium-ion batteries have raised prices and forced importers to hunt for alternative sources. Potential changes in the US–Mexico–Canada Agreement could affect the economics of using Mexico as a nearshore manufacturing platform for the US, including already-committed factory investments. And geopolitical tensions could threaten the access of manufacturers of electronic and renewable-energy products to critical minerals that are mined or processed in only a handful of countries. As nations compete to foster strategic industries, on the other hand, companies must weigh the potential opportunities created by proliferating government incentives and other industrial policies.

In addition, global companies must closely monitor regulatory developments. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), for example, requires importers to report the greenhouse gas footprints of many imported materials. Eventually, the EU will assess levies on emissions associated with a wide range of goods when a carbon price has not been assessed in their country of origin. The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, which is scheduled to go into effect in 2027, requires large companies to monitor and mitigate potential risks to their supply chains posed by human-rights violations and environmental regulations.

Developing a Best-Value Sourcing Strategy

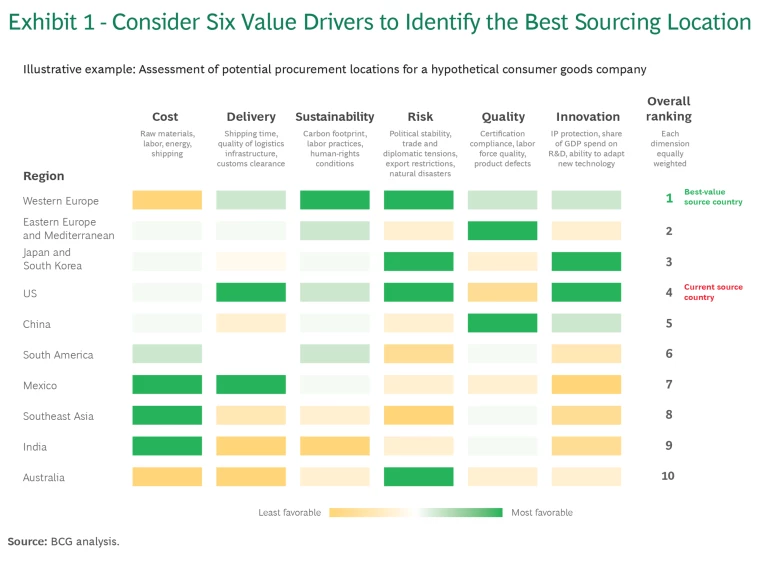

When choosing a location (or locations) to source from, we suggest that companies move from the traditional, best-cost approach to a best-value approach that incorporates broader considerations. This requires a holistic assessment of locations and supplier relationships. Buyers should develop a scorecard that considers six sourcing value drivers. (See Exhibit 1.)

- Cost. In addition to direct costs such as labor, land, energy, taxes, shipping, and tariffs, factor in dynamics that could change those costs—such as signs of labor shortages that could drive up wages.

- Delivery. Estimate the time needed to finish goods, ship, and clear customs before reaching specific markets or production facilities. Also evaluate the quality of logistics infrastructure.

- Sustainability. Factor in environmental, social, and governance criteria, which are becoming increasingly important in many markets. Carbon emissions, labor and human-rights practices, and the location and means of harvesting agricultural products are among the key considerations.

- Risk. Consider the risks associated with geopolitics and trade tensions under various scenarios. Also weigh the potential impact of natural events such as earthquakes, floods, and intense heat waves.

- Quality. Consider both the quality management record and compliance capabilities of specific suppliers, such as their ability to meet ISO9001 standards, as well as the quality standards of the country. Also consider labor force quality.

- Supplier Innovation. Assess the R&D capabilities and intellectual-property protections of specific suppliers and the countries where they are based or where they manufacture their products.

The weight that companies assign to each of these procurement value drivers, as well as the specific metrics, will depend on their products, goals, competitive position, and regulations in end markets and the country of origin, among other factors. Procurement officers and general managers will need to make tradeoffs.

For many very price-sensitive goods, the lowest-cost country may remain the best option. In other cases, sustainable manufacturers may have an edge. While a mill in Asia may offer the lowest prices for a European importer, for example, its steel may be assessed a high carbon tax under CBAM. So the importer may conclude that it’s better to pay more for “green steel” from the EU. Indeed, companies wanting to be seen as leaders in environmental sustainability may be more willing to pay higher premiums for green products than those content with being followers.

The degree of perceived risk is another important consideration. A company that believes there is a high risk of armed conflict or a trade action that could disrupt shipments of crucial materials or components from a particular country may be more willing to pay a higher risk premium for an alternative source for those goods than companies that believe the odds are low.

On the other hand, risk in some countries can mean opportunity in others. By shifting manufacturing or procurement of certain renewable-energy systems or critical materials to the US or Europe, for instance, companies may be able to take advantage of government incentives aimed at promoting strategic industries.

An Approach to Managing Geopolitical Risk

We suggest the following three-step approach to anticipating and managing the impact of such geopolitical risks:

- Monitor global developments. A robust system for mapping and continuously monitoring geopolitical risks is essential for resilient supply chains. This system should track current developments as well as potential future risks. Companies should not only try to prepare for potential unpredictable black-swan events; they should also constantly monitor grey-rhino events—developments that are unfolding in plain sight but that are often ignored until it is too late.

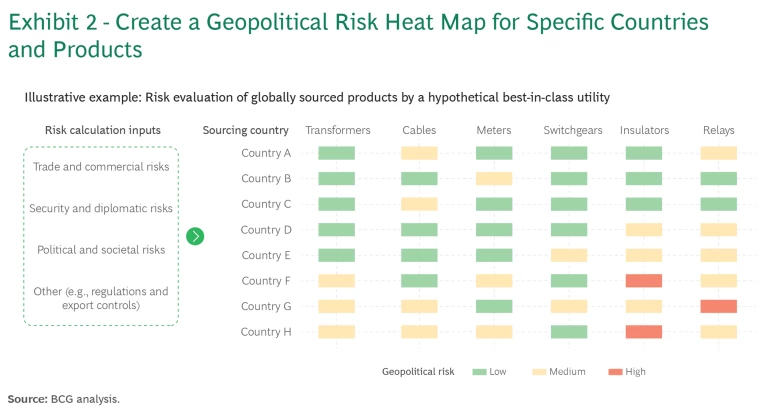

Create a geopolitical risk heat map to assess possible sources of disruption in both specific countries and specific product categories. Develop an aggregated country risk index with four types of inputs: trade and business climate metrics, assessments of national security and foreign relations, indicators of internal political stability and societal health, and “other”—such as regulations and export controls. (See Exhibit 2.) Tailor the index to reflect risks associated with specific products or materials. Access to energy and raw materials may be particularly vulnerable to sanctions or trade restrictions, for instance, while technology transfer controls and import bans could heavily impact electronics procurement. The risk heat map should also highlight potential opportunities driven by geopolitics, such as government incentives.

Develop scenarios for key risks that include signposts and trigger points, KPIs for estimating the business impact, and contingency plans.

- Improve supply chain transparency. Have a clear, up-to-date picture of the global footprint of your supplier network. Also gain transparency into the global manufacturing and procurement footprints of tier one suppliers and their (tier two) suppliers.

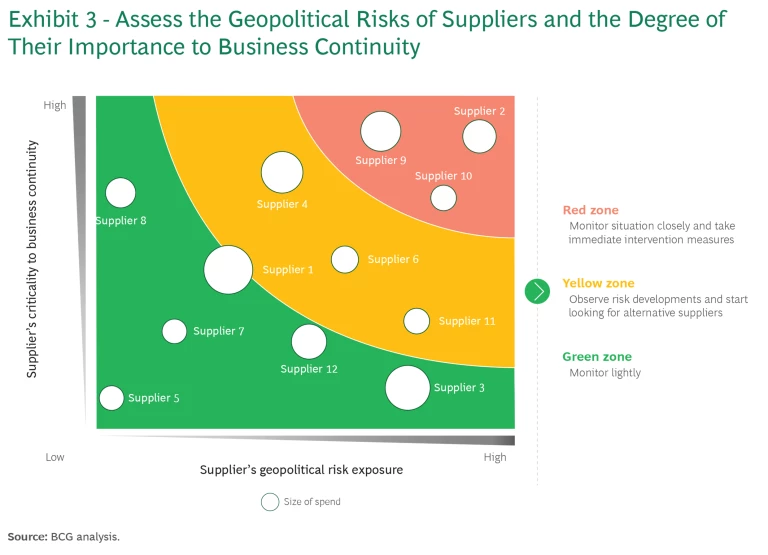

- Assess suppliers’ risk exposure. Evaluate the geopolitical exposure of your suppliers to identify possible choke points and the degree of their importance to business continuity. Construct a matrix, as shown in Exhibit 3. Plot geopolitical risk exposure on the x-axis based on a supplier’s global production and procurement footprint. A supplier with manufacturing in multiple countries may be better positioned than one with production in a single country to shift production, if needed, to countries with lower risk profiles. On the y-axis, indicate how essential that supplier is to business continuity. Factors include the availability of alternative suppliers and the timeline for establishing new partnerships. If it’s relatively easy to switch suppliers or manufacturing locations, criticality is low. A supplier in a monopoly position—perhaps because it’s the only one qualified or the only one with a proven technology—is likely critical. If that supplier ships from a nation that presents significant geopolitical risks, it may be wise to reassess business models or consider ways to encourage the development of alternative suppliers.

Strategies for Building a Resilient Global Supply Chain

The most obvious strategy for addressing geopolitical risk is to shift sourcing or production to other countries. The current trend toward more regional and diversified supply chains is driven, in part, by this logic. Intel has stockpiled semiconductors as insurance against the possibility of another global shortage like the one experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Other companies are embedding environmental and human-rights criteria into their proposal requests in preparation for regulatory changes in the EU and other markets.

CPOs can consider several other options for mitigating geopolitical risk:

- Extend the supply base. Establishing a local network of suppliers or one that is spread across several countries is the first step in building resilience. An extended supply base can diminish the odds that shortages of critical parts and materials will occur. Apple has diversified geographically by working with its main supplier, Foxconn, to manufacture in India, Mexico, and Vietnam, for example, while Tesla has added (or plans to add) facilities in China, India, and—potentially—Mexico to serve nearby markets.

- Deepen supplier relationships. Stronger executive-level ties with suppliers can help companies better anticipate and react to geopolitical risks. If the relationship is strong, suppliers can provide advance warning of political or policy shifts that could affect your business—and help find solutions. If a development results in shortages, they can also give their best customers priority access.

- Optimize specifications. Some supply constraints can be mitigated by changing design specifications. That can be challenging, of course, if certain parts are available from only a few suppliers. Tesla found a way to keep production on track during the recent global semiconductor shortage: it redesigned products and software to require less complex chips.

- Vertically integrate. Companies can also mitigate geopolitical risk by acquiring capabilities currently handled by suppliers or developing them internally. Major US automakers, for example, have invested in lithium mining as well as in lithium-ion battery manufacturers to secure a stable supply of a material that is critical to battery production. Vertical integration allows companies to control more of their supply chain by reducing reliance on external sources that may be affected by geopolitical upheavals or new trade restrictions.

Building Geopolitical Muscle

Geopolitical risk management is not only a procurement and supply chain challenge. It’s an organizational imperative. To build supply networks that deliver the best overall value, companies need the right geopolitical capabilities and expertise to identify risks and implement mitigation strategies on an ongoing basis.

Start building geopolitical muscle by training sourcing professionals in geopolitical analysis, data interpretation, risk management, and strategic sourcing. This will help them make informed decisions quickly. Understanding the implications of sanctions or a new trade agreement, for example, requires knowledge of the geopolitical context and the ability to swiftly assess the risks and opportunities for the supply chain presented by new developments. Teams should strive to anticipate events, rather than just react to them, and press-test investment decisions against various scenarios of how global events might unfold. Hiring people with diverse backgrounds can bring different and useful points of view.

Cross-function collaboration is essential. For example, insights from geopolitical risk analysis should be incorporated into financial planning and strategic business development decisions as well as into procurement. A central unit, staffed by either dedicated or designated employees, should capture and analyze external signals from across the organization—just as salespeople collect and share information from their customers. Manage performance by monitoring KPIs based on internal and third-party data for exposure to geopolitical risk and ESG improvement. Best-in-class companies have built digital risk radars to monitor the exposure of suppliers.

Global sourcing is no longer just about cost, quality, and delivery. It’s also about building resilient supply chains capable of withstanding changes in the global environment and ensuring business continuity. To navigate the complexities of international trade and politics, CPOs must leverage new technologies and strategic foresight in close collaboration with suppliers and key stakeholders. A holistic, strategic approach to procurement can deliver greater value, sustainability, resilience, and competitive advantage in an unpredictable global market.