Satellite communication (SATCOM) is becoming mission-critical for governments in both defense and non-defense applications—but capacity can’t keep pace with demand. Worse, governments likely can’t acquire new capacity using traditional procurement processes, which tend to be slow and cumbersome. Instead, governments need to understand the market dynamics facing commercial satellite providers and apply a wider range of procurement options.

Specifically, they should update their commercial SATCOM acquisition strategy to include reserve capacity from commercial providers under flexible terms. This means that during times of crisis, nations could—at a moment’s notice—access capacity that would otherwise be available for communication and general use by the public. They will not simply have more commercial capacity—they’ll also have the flexibility to shift it when and where it is needed.

Connectivity Is King

In the defense context, nations rely on satellites to enhance military operations and humanitarian aid, enabling commanders to coordinate operations, gather intelligence, and stay apprised of a current situation. Military GPS and satellite-based navigation systems use SATCOM signals to provide location data for troops, vehicles, and aircraft. Additionally, SATCOM networks are increasingly essential for securing military communication channels and defending against cyber threats. In the Ukraine and other conflict zones, satellites have been widely used to replace land-based communication infrastructure that has been damaged or destroyed.

Beyond military applications, SATCOM is now a key component of civilian infrastructure—especially in a crisis, when terrestrial mobile networks may fail or get overwhelmed. During the Maui wildfires, for example, disruptions in cell service prevented civilians from contacting emergency support teams and finding the best route to safety. SOS-enabled phones provided a critical capability to relay communications between civilians and emergency services, but availability was not widespread. In such situations, SATCOM ensures that people in even the most remote areas can access resources, information, and emergency alerts.

This dual role positions SATCOM as an indispensable technology bridging both defense and civilian sectors, contributing to the resilience of societies facing diverse challenges.

Government Capacity Cannot Keep Pace with Demand

Despite the growing importance of SATCOM technology, government-owned satellites often have insufficient bandwidth to meet day-to-day needs—let alone the surge capacity required to respond to a large-scale crisis. To meet the growing demand, governments are leveraging their buying power and capitalizing on the recent growth of the commercial SATCOM industry. For example:

Government-owned satellites often have insufficient bandwidth to meet day-to-day needs—let alone the surge capacity required to respond to crises.

- NATO recently allocated €1 billion in funds to receive SATCOM services from France, Italy, the UK, and the US over the next 15 years.

- The EU allocated €2.4 billion to establish the new Infrastructure for Resilience, Interconnectivity and Security by Satellite (IRIS2), Europe’s first multi-orbital satellite constellation to enable connectivity and communication among satellites of different types. IRIS2 will help bolster existing programs such as Copernicus, the earth observation component of the EU’s space program. (See “SATCOM for Climate and Sustainability Monitoring.”)

SATCOM for Climate and Sustainability Monitoring

- Governments are also looking to enhance SATCOM capabilities through public-private partnerships, leveraging the growing number of privately owned and operated satellites. For example, the Spanish Ministry of Defense (MoD) partnered with SATCOM provider Hisdesat, leasing capacity from Spainsat at an estimated spend of €15 million per year. The partnership allows Hisdesat to commercialize any capacity that the MoD does not need.

- Similarly, the US Department of Defense (DoD) is looking to create additional flexibility by leveraging private SATCOM companies to provide surge capacity in times of elevated risk. (See “The DoD’s On-Demand Approach.”)

The DoD’s On-Demand Approach

The base CASR level—the minimum capacity required to meet day-to-day operations—has the highest predictability and lowest urgency, calling for long-term contracts with reliable providers that pass commercial due diligence. But in circumstances requiring elevated CASR levels, such as responding to an international crisis, the program would afford coverage at a moment’s notice.

Shifting Market Dynamics for SATCOM Providers

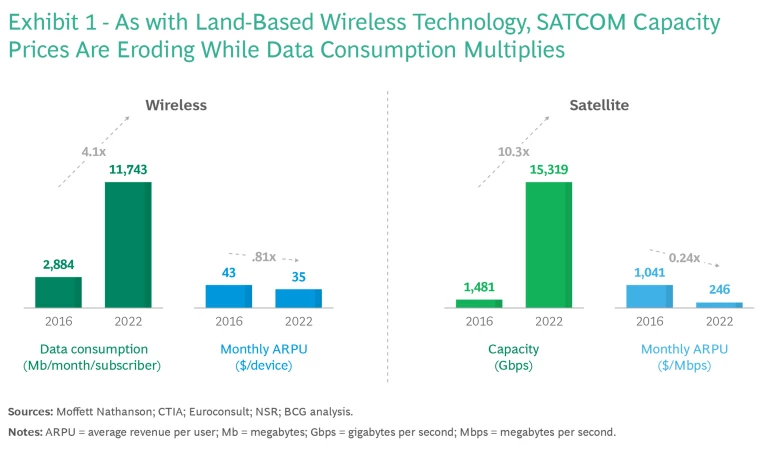

As governments seek to increase their SATCOM capacity, they need to understand current industry trends. One key factor is the growing pressure on commercial satellite companies, many of which must develop new service offerings and revamp their business models. As with land-based telecom networks, the commercial SATCOM industry is being commoditized. Service offerings are not differentiated—capacity from one provider is pretty much identical to that from any other—and despite the growth in data consumption, prices are declining. Between 2016 to 2020, network capacity has increased 2.5 times, while the average revenue per user has dropped by half. (See Exhibit 1.) As a result, the SATCOM industry overall has been losing money for several years.

In addition to unit economics, governments should factor several other trends into their SATCOM strategy. (See Exhibit 2.) For instance, the cost to build and launch satellites has declined—particularly for low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites, which are smaller and operate at lower altitudes than earlier generations. Regulatory shifts may limit the market for LEO satellites, potentially creating pricing power for a smaller number of players.

Another complicating factor is that governments have more stringent requirements than other SATCOM customers, limiting the number of providers they can work with. For example, systems must be highly resilient and hardened against tampering or cyber attacks. Rapid developments in geostationary satellites and LEO and medium Earth orbit (MEO) technologies, along with other advances, will unlock rapid growth and new use cases. Given these advances, governments need SATCOM providers that can innovate to keep pace with new developments, continually improve performance, and offer new applications as well as integrated/optimized services.

Four Keys to Acquiring Reserve SATCOM Capacity

Ample commercial SATCOM capacity is available across spectrum bands, orbits, geographies, and providers. But governments need a smarter and more flexible approach to access that capacity, particularly in times of elevated need (such as during natural or manmade disasters). We believe they should focus on four main areas.

Understand the SATCOM market and supplier economics. In our work with DoD suppliers across more than 70 initiatives, we see commercial SATCOM providers using a range of tactics to obscure their true costs, especially for complex programs. As a result, governments routinely overpay. (The rest of the defense industry faces a similar dearth of information in working with suppliers.) For any major acquisition strategy, it’s critical to reduce this information asymmetry with vendors.

Any acquisition approach should start with an assessment of the overall SATCOM market to understand vendors’ competitive positioning, current trends affecting the market, and key drivers of revenue, profit, and overall financial performance of industry players. Standard approaches such as internal and external benchmarking and supplier analytics, along with proprietary tools, can help governments get closer to the truth regarding the lifecycle expenses for a specific system or program.

Set clear reserve capacity requirements. Although capacity requirements will clearly increase, they won’t happen in predictable, linear fashion across spectrum bands, orbits, and geographies. Governments will thus have to systematically define their capacity needs across a range of scenarios—particularly the surge capacity required in a crisis. They must also clearly define acquisition terms, service-level agreements aligned to key metrics (such as coverage, throughput, or latency) across different demand levels and scenarios, and other contractual elements. This alignment is crucial to guarantee that the SATCOM capacity is available as needed, without any bottlenecks or misunderstandings.

Acquisition terms, service-level agreements aligned to key metrics, and other contractual elements are crucial for governments to get SATCOM capacity as needed, without any bottlenecks.

Responding to an international crisis (e.g., elevated Commercial Augmentation Space Reserve levels) will likely require global coverage at a moment’s notice supported by both US and non-US providers. This risk could be hedged by contracting with providers among the “Five Eyes” alliance of countries—Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK, and the US—that routinely share intelligence with each other. Any SATCOM acquisition approach will require the development of a robust structure aligned to existing national security frameworks. Such a structure would likely extend beyond the existing expertise and offerings of commercial SATCOM providers.

Negotiate from a position of strength. After determining which services and bandwidth are necessary to meet mission goals, governments can identify a subset of potential providers and conduct the due diligence to establish whether a specific company can meet their needs. To support that process, it’s critical that governments rethink the acquisition process, including setting performance expectations and incentives. Understanding the financial objectives and typical tactics of commercial SATCOM providers can give governments an information advantage during negotiations.

Financial incentives will likely have the greatest influence. Tactics such as dynamic pricing models can set pricing in a way that supports a swift response to capacity needs. Premium base pricing, akin to retainers, recognizes that providers will likely forgo other opportunities and commitments to supply capacity to governments when required. Nonfinancial incentives are also attractive. For example, governments can help providers overcome regulatory barriers and connect them to other government and commercial entities.

Provide incentives for innovation. SATCOM technology has advanced significantly over the last 20 years, with more changes to come. Rapid developments in geostationary satellites, LEO and MEO technologies, and semiconductors will lead to new types of satellite terminals and use cases. For example, multi- and steerable-beam systems can direct SATCOM capacity on demand, and terminal technologies can enable seamless switching between satellites at different altitudes to make signals more resilient. Similarly, AI, IoT, and edge-computing applications will unlock a range of new services that governments will likely need.

Governments should factor advances in SATCOM technology into their acquisition strategies, providing incentives for commercial providers that invest in key applications.

Governments should factor these advances into their acquisition strategies, structuring contracts with incentives for commercial providers that invest in key technologies. One potential incentive—with benefits for both sides—is for governments to become “anchor” customers for providers that provide the most attractive new applications.

At a time of increased disruptive weather events, growing geopolitical tension, and other factors, SATCOM is a baseline requirement for reliable connectivity. Governments are taking steps to increase their SATCOM capacity. But they cannot apply the procurement playbooks of the past. By focusing on the four areas we identified, governments can develop acquisition strategies that are adaptive, cost-effective, and aligned with the evolving landscape of satellite technology and services. In doing so, they can ensure that military personnel have the tools to operate effectively and that civilians are safe, informed, and able to access critical services in times of crisis.