As US health systems struggle to adapt to some of the most challenging economic conditions they have seen in recent history, they can look to an unlikely source for guidance: the aviation industry .

The two industries have many parallels. Like health care , aviation is a highly regulated industry with an extremely skilled, limited workforce and a strong focus on safety. To maintain profitability in the face of high overhead costs, airlines have relied on passenger volume, as well as on revenue from business-class passengers; similarly, health care systems rely on procedure and inpatient volume, as well as on higher revenue from commercial health plans. Of course, the industries also have some significant differences. In particular, health care is often non-elective, whereas people can choose not to fly. Nonetheless, health systems can gain many insights from aviation.

In the early 2000s, the aviation industry was at a crossroads, as skyrocketing fuel prices and shrinking passenger demand resulted in overcapacity. A wave of airline bankruptcies and consolidations followed. But then the aviation industry went further: It fundamentally changed its business model through revenue diversification and creative investments. These measures stabilized the industry and permitted profitable growth in the face of economic uncertainty.

The health care industry has taken similar steps toward consolidation in recent years. But consolidation and belt-tightening measures will not be enough to position the industry for a financially sustainable future. In order to prosper, health care systems, like the aviation industry, will need to make a fundamental shift in their business model to embrace new kinds of investments and diversify their revenue.

Health Systems Face Serious Economic Headwinds

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated longstanding economic challenges in the health sector. For every month of 2022, average operating margins across the acute-care sector were negative. Nineteen hospitals closed or declared bankruptcy.

Commercial and Medicare rate increases have been inadequate to compensate for cost increases, especially labor costs. If current trends continue, the typical health system will need to increase rates by 5% to 8% per year—twice the annual reimbursement growth rate of the past decade—in order to break even in 2027.

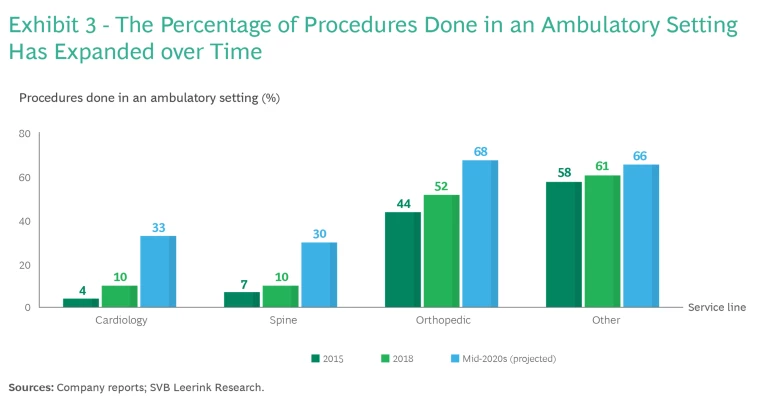

Although volumes for some hospital procedures have gradually been returning to pre-COVID-19 levels, the continued patient migration toward non-health-system-affiliated outpatient facilities such as ambulatory surgical centers for high-margin orthopedic, cardiac, and other procedures erodes health systems’ financial stability.

Last year BCG projected that, without significant intervention, the annual financial shortfall of US health systems will exceed $200 billion by 2027 .

Consolidation and Cost Cutting Provide Short-Term Stability

Presented with its own set of economic challenges in the early 2000s, the aviation industry underwent a dramatic consolidation. In 2000, ten airlines accounted for more than 90% of available seats in the US. By early 2012, those ten airlines had merged into five that controlled 85% of the market. Consolidation did not stop after 2012 (as evidenced by the merger of Alaska and Virgin America airlines in 2014, the prospective merger of Spirit and JetBlue announced In 2022, and the prospective merger of Alaska and Hawaiian Air announced in 2023), but it did slow substantially.

To improve their financial footing the airlines also focused on efficiency and cost reduction measures. They enhanced the fuel efficiency of their propulsion systems and used lighter-weight materials to minimize fuel consumption. They improved air traffic management and runway setup, and used technology to minimize holding patterns, respond to changing weather patterns, and fly the optimal route.

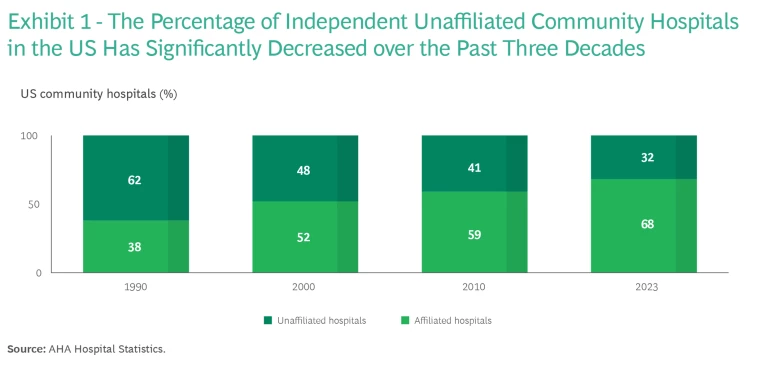

Health systems have tried similar approaches to address their ongoing economic challenges. In the early 2000s, they began acquiring hospitals and medical practices, consolidating into multihospital systems. As a result, the number of independent unaffiliated hospitals has fallen by almost half, from 62% in 1990 to 32% in 2023. (See Exhibit 1.) In the past five years, however, as the number of independent hospitals and medical practices has dwindled, the number of transactions has dropped, even as the average transaction size has grown. We have also seen consolidation in payers, an area where most of the growth has involved Medicare Advantage members captured by the top four payers.

Regardless of their size, these partnerships and acquisitions aim to grow patient volume and expand the health system’s clinical footprint. Ideally this leads to economies of scale achieved through consolidation of shared services and the ability to offer a more attractive network to payers. Patient care benefits, too—as a result of care coordination between local hospitals and patients’ access to a more comprehensive continuum of care.

In addition to pursuing consolidation, health systems have sought to cut costs and become more efficient by streamlining procurement contracts, reducing the length of hospital stays, and improving operating room turnaround time, among other measures. They have also increased their focus on purchasing and administering drugs in a financially sustainable way. Such changes have found some success, but as health systems run out of low-hanging fruit to gather, they must think beyond traditional cost-cutting efforts.

Airlines’ Diversification into New Businesses Offers a Blueprint for Health Systems

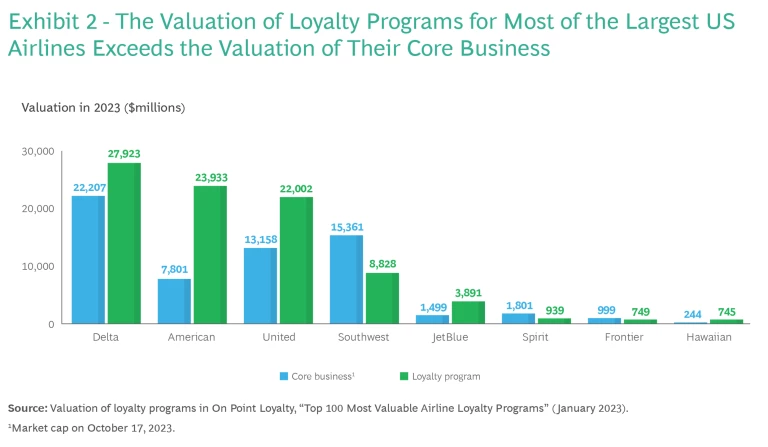

To achieve greater financial sustainability, airlines took the bold step of fundamentally shifting their core business, diversifying beyond transportation-related operations. In a major pivot, they embraced a surprising business model: providing financial services to attract and retain customers. Specifically, they invested heavily in loyalty/credit card programs. These programs have far exceeded the companies’ initial expectations. In 2023, the valuation of the loyalty programs of the top three airlines—Delta, American, and United—actually exceeded the market cap value of the airlines’ core businesses. (See Exhibit 2.) These programs have provided crucial economic stability. When the airlines’ core business has performed poorly, the loyalty programs have enabled them to mitigate their losses or even preserve profitability.

Airlines have also expanded into vacation packages and data monetization, and they have launched corporate venture funds to invest in new technologies.

To Thrive, Health Systems Must Seek Opportunities with New and Diverse Partners

Health systems have begun to pursue similar revenue diversification, although providers have only scratched the surface so far. We believe that there is much more opportunity for bold changes in the business model. Most notably, we see five promising avenues for provider revenue diversification, ranging from core care delivery to relatively frontier or innovative approaches: investing in ambulatory surgical centers, expanding into provider-sponsored plans, making new capital light/risk light investments, pursuing nontraditional partnerships, and investing in commercializing research assets via a biotech spinoff.

Invest in ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs). As care has shifted from the hospital setting to the outpatient setting, high-margin surgeries have shifted to ASCs. (See Exhibit 3.) For example, by 2025, more than two-thirds of orthopedic procedures will likely be performed in ASCs, and the proportion of cardiology procedures performed in those facilities will increase substantially as well, to about 33%. The aging population and rapid growth of Medicare (over 11,000 people age in to Medicare daily) are fueling a need for more and better outpatient capabilities. In many cases health systems have been reluctant to embrace this reality and invest in ASCs, however, because procedures performed there are reimbursed at lower rates than the same procedures performed in a hospital outpatient department setting. As a result, many ASCs today are owned by surgeons or physician groups, and health systems can’t capture that revenue.

The expected growth of ASCs may create new entry points for health systems, including through partnerships with national surgery chains and oncology chains, or by expanding into physician-owned surgery centers as an equity partner. These approaches can enable health systems to expand in the ambulatory setting despite capital constraints.

Acquire provider-sponsored plans (PSPs). Providers have a long history of expanding into the payer industry through PSPs, a trend that accelerated during the 1990s. Although providers have had mixed success with PSPs, they have fared best in markets where the population is receptive to a narrow or semi-closed network and managed care. Health systems that operate PSPs must have a strategic reason to do so and must be able to manage utilization, improve outcomes, and reduce unnecessary medical spending. This agenda can seem counterintuitive for systems that have historically generated revenue by expanding market share and increasing volume. Providers often underestimate the capabilities required to successfully operate as a payer, including actuarial, utilization management, network design, and STARS ratings (on which federal performance bonuses are based).

The most successful PSPs have invested in early development of these capabilities, either organically or through partnerships. They have also invested in value-based care delivery, pursuing better outcomes at lower cost, investing in population health, and prioritizing service-based value-based care (for example, timely, accurate care that delivers a good patient experience).

Make capital-light, risk-light investments. Over the past decade, private equity firms have invested in a wide range of health care services, including dental, vision, orthopedics, and gastroenterology, as well as home care, urgent care, and primary care practices. Health systems could co-invest with private equity firms in specialty practices, home health, and other areas, owning equity in these groups as a way to diversify their investment base.

In addition to funding specialty practices and home health, private equity firms have invested in a range of other business models of potential interest to health systems, including complex care management, clinical protocol development, value-based care capabilities, and solutions to address social determinants of health.

Pursue nontraditional partnerships. Many retail and nontraditional organizations, including Amazon and Walmart, have entered the care delivery space. As nontraditional companies expand into health care, they will need strong health system partners that can provide comprehensive services to the patients they attract. In addition to retailers, providers of nonclinical services such as ModivCare, UniteUs, and Tivity Health have partnered with health systems. These organizations have a particular focus on social determinants of health such as food insecurity and social isolation.

Consider smart divesting. Many health systems with research capabilities—especially academic medical centers—have successfully spun off new biotech companies. For example, Cleveland Clinic spun off CVD diagnostics, which Quest Diagnostics subsequently acquired for $94 million in 2017. Similarly, Juno Therapeutics emerged in 2013 from a collaboration of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Memorial Sloan Kettering, and Seattle Children’s Research Institute. Five years after an initial investment of $120 million, it was acquired by Celgene for $9 billion. Divesting a portion of the business into a standalone for-profit entity is a high-risk, high-reward way to diversify revenue, while also attracting top physicians, scientists, and patients in a flywheel effect.

Conclusion

The aviation industry and health systems have many parallels. In both industries, economic hardship has led to consolidation, cost cutting, and now a need to diversify revenue streams and change the business model. Ultimately, by looking across industries, including at the aviation industry, health providers can learn lessons about what has worked and what hasn’t worked. For example, providers may choose to be more precise in cost cutting and to avoid across-the-board cost reductions, which can lead to poor customer (or patient) experience and problems with operational reliability or care quality.

Overall, a fundamental shift in the aviation industry’s business model through revenue diversification and creative investments was essential to the industry’s survival. A similar shift will likely be essential to the survival of health care providers. The US is counting on its health systems to evolve in response to powerful economic pressures. Leaders who can see beyond the present challenges to spur innovation and next-level performance are essential to realizing that future.

We thank the following individuals for their contributions to the article: Allan Baumgarten, University of Minnesota; Qifang Bi; Julia Eleuteri; Pierre Galvin; Marisa Lehti-Brown; and Madeline McCloughan.