For the CEO

A message from our editor in chief on this critical topic.

Two years into evolving Parsons Corporation from a privately held engineering construction management firm into a publicly traded, technology-focused powerhouse, Chuck Harrington had what he describes as an “a-ha” moment.

“We were transforming our markets, our services, the type of people we were hiring, and our capital structure, which resulted in going public,” says Harrington, the company’s former chairman and CEO. “There were just so many moving parts and issues surfacing on a daily basis. I realized I needed someone else—a partner—who could augment capacity and complement my strengths.”

For Harrington, that person was Virginia Grebbien, the former chief of a public-sector utility and a senior leader at Parsons, who became his chief of staff (CoS) in 2016.

I realized I needed someone else—a partner—who could augment capacity and complement my strengths.

Chuck Harrington, BCG Senior Advisor and former Chairman and CEO, Parsons Corporation

“Chuck and I had a good six years of working together in a business development and P&L capacity," says Grebbien. “When it came right down to it, my P&L and board experience complemented his experiences.”

Together, they formed a C-suite dream team: Harrington driving the creation of the strategy and execution plan for the transformation; Grebbien engaging the board, leadership, employee base, and outside stakeholders to identify and help solve emerging challenges before they became big ones.

Three and a half years after they joined forces, shares of Parsons opened for trading on the New York Stock Exchange, closing 11% above their offer price on the first day of trading.

“It was a high-risk, high-reward strategy that paid off handsomely,” says Harrington, who is also a BCG senior advisor. “And [it] continues to pay off very well for the original employee shareholders and our public shareholders as well.”

That outcome bears testament to how a well-chosen, well-supported CoS can dramatically elevate a CEO’s performance. But a pairing as successful as Harrington and Grebbien’s is not guaranteed. If a CEO chooses someone with the wrong background or temperament, or fails to manage them well, it can make the chief executive’s job even harder.

Building a Successful CEO-CoS Partnership: Five Questions to Ask

To get what is arguably their most important C-suite relationship right, CEOs need to first identify a potential CoS with promising qualities and then set them up to excel in the role.

It’s a process that requires self-reflection, trust, and the most precious of CEO resources: time. But the investment can pay off handsomely. Because when it works, CEOs get more than a glorified EA who helps them manage their time better. They get a strategist, a trusted thought partner, and even a proxy who complements their strengths, amplifies their reach, focuses their priorities, and reduces their mental load—helping them realize their fullest potential as a leader.

More Than a Gatekeeper

The chief of staff role first came into its own during the time of Napoleon, when the sheer scale of conflicts sweeping Europe gave rise to armies too big for a single commander to control

The position entered the political sphere in the 20th Century, with US President Dwight D. Eisenhower designating Sherman Adams as the first White House chief of staff. Nicknamed the “abominable ‘no’ man,” Adams directed the daily operations of the White House, resolving issues between cabinet members and acting as both a curator of information to the president and strategic

In recent decades the role has spread to the private sector, gaining traction in the 2010s before exploding in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath.

“The role has accelerated because the context in which CEOs operate now is much less stable and more dynamic than it was five years ago,” says Christine Barton, a BCG managing director and senior partner. “The number of stakeholders and their expectations of CEOs have also greatly expanded.”

The growth of the Chief of Staff Network, a professional association, captures the increasing popularity of the role. Started in 2016 as a small dinner club in New York City, today it has over a thousand members globally, almost all of whom work in the private sector.

The [chief of staff] role has accelerated because the context in which CEOs operate now is much less stable and more dynamic than it was five years ago.

Christine Barton, Managing Partner and Senior Director

“A chief of staff could be an executive assistant, or they could be a CXO, or they could be anything in between,” says Rahul Desai, general manager of Chief of Staff Network. “What we find is that the lowest-level chiefs of staff, the EAs, work at very small companies, while director level and above work at the biggest.”

That spectrum reflects how CEOs of large, complex enterprises often need more than a CoS who keeps the trains running on time. Whether they’re leading a digital transformation, managing geopolitical risks, spearheading cybersecurity strategy, or guiding other initiatives, CEOs can unlock tremendous value from a right hand who can also influence a company’s direction of travel.

“The more modern models are really about effectiveness,” says Barton. “They’re about accelerating the CEO’s priorities and amplifying the CEO.”

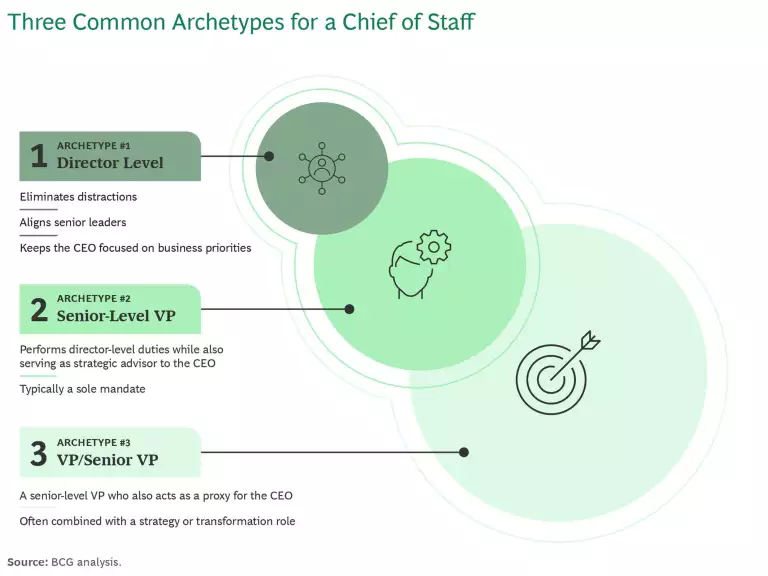

She advises CEOs to think of a CoS across three possible archetypes: a director-level CoS who eliminates distractions, harmonizes senior leadership, and helps the CEO stay focused on strategic priorities; a senior-level VP who assumes all of those duties and also serves as a strategic advisor; or a VP/SVP who does all of the above and acts as a proxy, extending the CEO’s visibility and impact inside and outside the organization. (See the exhibit.)

“When you expose CEOs to these other uses of a chief of staff,” says Barton, “they realize ‘Oh my gosh! I’m using pieces of a lot of different people to try to get an outcome that a chief of staff can get me to in a more efficient, effective way.’”

Finding the Right Fit

A successful partnership begins with finding a CoS who is the right fit, both for the CEO and the company they lead. Some corporate cultures, for example, may not lend themselves to the role.

That was the case for US Foods, a $30 billion food service distributor. “We’re a very low-cost, low-margin business,” says Pietro Satriano, the company’s former chairman and CEO and a current BCG senior advisor. “We ran so lean in all aspects of the business, it [a CoS] wouldn’t have sent the right message.”

Leadership by Design: Navigate the complexities of modern leadership

But when the culture is hospitable, a CoS can yield major dividends. “There’s nothing worse than being booked into a two-hour meeting where you’re wondering why you’re there, and why somebody else couldn’t be handling this for you,” says Iain Conn, a BCG senior advisor and former CEO of energy giant Centrica. “I think you can get material efficiency [with a CoS in the office of the CEO] through the way your time is managed; two to three times the effectiveness than you as an individual could otherwise deliver.”

Conn advises CEOs who’ve never used a CoS to spend time with leaders and organizations who have. “I think it's important that the CEO understands what the art of the possible actually is,” he says.

I think you can get material efficiency [with a chief of staff] through the way your time is managed.

Iain Conn, BCG Senior Advisor and former CEO, Centrica

Exploring the possible also includes self-reflection on the part of the CEO. “They have to understand what their strengths and weaknesses are,” says Grebbien.“It doesn’t strengthen or elevate a CEO if their CoS has the same strengths and weaknesses as they do.”

Once a CEO has a firm grasp of the type of leverage they can achieve with a CoS, Conn advises they start thinking about the ideal background for the role. “I think it’s dangerous to bring in a CoS from outside the company,” he cautions. “It’s not impossible, but I would counsel against it, because I think some institutional knowledge is really important.”

Judith Wallenstein, leader of BCG’s CEO Advisory, agrees that an external candidate is a tricky choice. But it can work. “If a CEO has to go external for lack of suitable profiles internally, it would be advisable to rotate the future CoS through a number of roles for at least six months,” she says.

Beyond capabilities—but just as crucial, says Wallenstein—is a candidate’s temperament. “You need someone with a lot of human maturity and a very acute read of organizational dynamics,” she says. “The risk of a young, hot-shot type is that it’s very difficult not to live on borrowed authority.”

This is especially true of a high-level CoS. “They spread both the priorities and personality of the CEO into the organization,” says Conn. “Done badly, it can be a massive barrier and can send signals that the CEO doesn't intend.”

You need someone with a lot of human maturity and a very acute read of organizational dynamics.

Judith Wallenstein, Managing Director and Senior Partner

It often boils down to how secure a CoS is letting others shine. Grebbien, for example, saw the CoS role as an opportunity to do “all of the fun things” a CEO gets to do without all the pressure of being in the limelight. “Probably in my 30s I wouldn’t have been okay with it, because I was a very ambitious person,” she says. “But at that point in my career, I’d already been CEO of a billion-dollar organization.”

A strong work ethic is also a must.

“We solicited data on how many hours a week our members work,” says Desai of the Chief of Staff Network. “By and large it’s sixty-plus.”

Another key trait is the ability to learn quickly.

“The chief of staff is a utility player,” says Grebbien. “You can put that person wherever you need them.”

Setting a Chief of Staff Up to Excel

Like all great relationships, a strong CEO-CoS partnership is founded on trust, something Harrington and Grebbien had established before she stepped into the role.

“One of the things that is very important to Chuck is trust and respect and following through on your word,” she says. “If he told me something, I would not say anything about it unless he was comfortable with it.”

Trust is also essential for a CoS to gain a comprehensive picture of organizational dynamics—and take work off the CEO’s plate.

“When the organization trusts them enough, they can often seek guidance from the chief of staff without ever having to go to the CEO,” says Conn.

Harrington’s trust in Grebbien was so complete, he had functions report directly to her. “She was not a minister without portfolio,” he says. “Strategy, government relations, public relations, marketing, all of those reported to her directly.”

When the organization trusts them enough, they can often seek guidance from the chief of staff without ever having to go to the CEO.

Iain Conn, BCG Senior Advisor and former CEO, Centrica

Along with trust, there needs to be a clear understanding of expectations. Here, too, a CEO’s self-awareness can spell the difference between success and failure.

“If a CEO structures the role for the CoS to challenge them, but they don’t actually like to be challenged, then that’s going to set that relationship up for conflict and friction,” Barton warns. “If they set the role up for leverage, but they will not let go of any of the interactions or any of the decisions, then they are not actually creating leverage for themselves.”

Once initial expectations are set, CEOs need to communicate their chief of staff’s remit to the senior leadership team.

“They need to be the one that says ‘Hey, this person is a member of our executive team, you will treat them as such, and they are my proxy in matters X, Y, and Z,’” says Desai.

CEOs also need to match their words with actions. “If the CEO is not consistent in his or her behaviors, the chief of staff can be undermined and rejected by the first team and organization,” Barton warns.

And though long hours are expected, CEOs still need to be mindful of how much work their CoS is taking on.

“Almost every chief of staff I see who’s just starting out ends up being overeager,” says Desai, “We surveyed our members to ask if they set personal boundaries to avoid burnout, and nearly half of them said ‘no’.”

Finally, CEOs need to ensure they are aligned with what happens when the CoS moves on to their next opportunity. “I think it’s very important that they don’t feel that they’ve somehow been anointed, and yet to attract high-potential talent the role must be seen as a route to career acceleration,” says Conn. “Having a conversation early on with them, while they’re in the role, about what they want to do next and landing them in what is seen to be a progression, once they leave the office, is really important.”

A chief of staff, even after retiring from their role, usually remains a strong ambassador of the CEO’s agenda.

Judith Wallenstein, Managing Partner and Senior Director

It’s a conversation that can continue to confer benefits to the CEO even after their CoS has moved on. “A CoS, even after retiring from their role, usually remains a strong ambassador of the CEO’s agenda,” says Wallenstein.

Building a Successful CEO-CoS Partnership: Five Questions to Ask

Finding a CoS is not something to be rushed. The following five questions can help launch CEOs on a promising partnership with a CoS that delivers the intended results—and beyond.

Is a chief of staff right for me and my company? Given the expanding list of demands on CEOs, many will undoubtedly see the value in having a CoS. But the position must align with the company’s culture and needs. “We were essentially a single-category, single-market company,” says Satriano, who opted to delegate the typical functions of a CoS among several people on his team at US Foods. But for CEOs running a global, multigeography, or multicategory company, a CoS may be the right move, he says. “If there’s a set of activities that do not fall neatly into a particular function, and there’s no one on your team who can fulfill those activities, you probably do need a chief of staff.”

Timing is also a key consideration. “At times of cost cutting, people might say adding a chief of staff can seem extravagant,” says Conn.

How can a CoS complement my strengths? An effective CoS is not a mini-me. Ideally, they bring qualities to the table that enhance the CEO. “Most CEOs don't think about a good complement to them in terms of the profile because a lot of CEOs are very cerebral,” says Wallenstein. “Sharp, fast analysts and decision makers don’t need that profile as a chief of staff. They need someone with huge intuition.”

But landing on those qualities often takes a high degree of self-awareness. “Many CEOs will distort their time based on their background, and what they find interesting and energizing,” says Barton, “whereas it needs to be either enabling value creation, or directly related to value creation.”

While most experts agree that internal candidates are easier to bed into the role, outside candidates can also work—but it takes more effort up front. “In insular cultures where there is risk of ‘not-invented here’ syndrome or organ-rejection, then the chief of staff may have to be internally sourced,” says Barton. “An external hire may have an extended onboarding and integration, which would impact the number of years he or she needs to be in the chief of staff role.”

Do I trust this person? And do they have the right temperament to be an effective CoS? A healthy, productive CEO-CoS relationship starts with trust—and the confidence that it will not be broken even after the CoS steps down. “Once the chief of staff moves on to their next role, they ‘forget’ anything sensitive they have learned,” says Wallenstein.

Hand-in-hand with trust is temperament. An effective CoS needs to be mature and confident enough to work behind the scenes—and not be acknowledged directly. “If you’re number two, you don’t get the credit and your name doesn’t go on the wall,” says Grebbien. “And a lot of times, you’re not in the picture, you’re taking the picture.”

A lot of times, you’re not in the picture, you’re taking the picture.

Virginia Grebbien, former Chief of Staff, Parsons Corporation

That is especially true for ensuring a smooth integration with the senior leadership team, many of whom likely ascended to their positions by being standout leaders of a business unit. “Find someone who will be happy if the people in the company—and notably, the executive committee members—look great in front of the boss, not if they themselves look great in front of the boss,” says Wallenstein.

What kind of expectations do I have of a CoS—and they of me? Even when CEOs trust their incoming CoS, it is essential to have a conversation with them—or even several conversations—at the outset to align around responsibilities and expectations. “There was a lot of communication between Chuck and I about exactly what the role would be, and how we would implement it so that I could be successful and deliver to him what he needed for his personal success and the organization's success,” says Grebbien.

The discussion should also include what happens when the CoS moves on from the role. “If the CEO places the CoS in a position that needs upgrading and will benefit strongly from someone who can ‘think like a CEO’ and take an enterprise perspective, the CoS gets an attractive development opportunity, and the CEO has found a—hopefully—unobtrusive way to deeply transform a given role,” says Wallenstein.

Are my words and actions setting up my CoS for success? Authority doesn’t automatically convey to a chief of staff just because the CEO has hired them. The executive team needs to hear it directly from the CEO’s mouth. “The CEO needs to think about communicating with the first team how they intend to use the chief of staff and their expectations for the integration,” says Barton.

The CEO should also prepare to shake up how they engage with their senior leadership team. “In all likelihood, the CEO will need to make changes to how he or she currently works,” says Barton. “The CEO has to be willing to do that work.”

CEOs never have enough hours in the day. And the demands on their time are only growing as the environment in which they operate becomes ever more complex, challenging, and fraught with risks. But with a well-chosen, empowered chief of staff who complements their strengths, CEOs not only can claw back precious time—they can make the most of it.

Patricia Sabga is the executive editor of The CEO Agenda.