Transformations are critical to building competitive advantage and delivering shareholder value, especially in fast-changing industries. But 70% of transformations fail to achieve their initial goals. Acting as a nerve center that coordinates many workstreams, timelines, and priorities, a transformation office can help companies flip the odds.

Transformations are inherently difficult, filled with compressed deadlines and limited resources. Executing them typically requires big changes in processes, product offerings, governance, structure, the operating model itself, and human behavior. They demand financial discipline, a stage-gate methodology, rigorous tracking, cultural change, and issue resolution. All these factors favor the creation of a transformation office (TO).

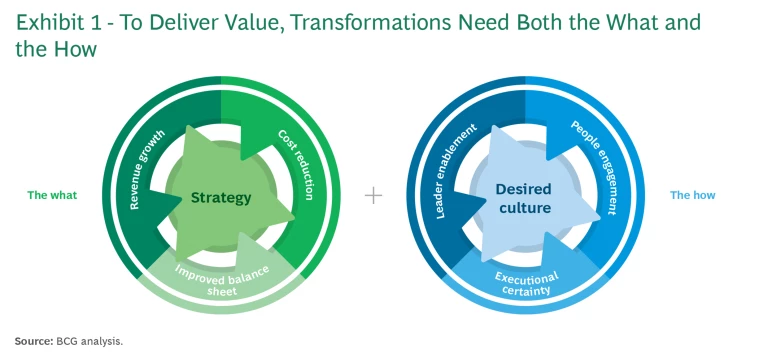

Organizations often just focus on the strategy they will pursue and the value they expect to deliver in a transformation. But while it’s important to concentrate on value delivery (the what), teams must also look at changing people’s behavior and mindset (the how). Our approach to “the how” of transformation seeks to change behavior and the way people work by concentrating on four elements. (See Exhibit 1.)

- Desired culture: creating the right environment to bring target behaviors to life

- People engagement: supporting, motivating, and upskilling the organization

- Leadership enablement: aligning leaders and enabling them to drive the change

- Executional certainty: establishing a strong TO with the tools and mechanisms to track and deliver results

In this article, we focus on the element that organizations frequently neglect: executional certainty, which starts with establishing the TO and kicking off the transformation. Many leaders believe their companies are disciplined enough to transform without a formal office.

But that’s rarely the case. Our experience and the data suggest that a TO can improve value creation by up to 50%. It can help speed value delivery while improving transparency and accountability. By centrally managing the mechanics of a transformation, a TO frees up business leaders to execute and deliver the goals of the endeavor.

A TO offers many benefits:

- Program Consistency. A TO allows every element of the program to be measured, tracked, and made transparent.

- Momentum. A TO pulls in the most senior leaders of an organization, reinforcing the idea that the transformation is a collective responsibility.

- Impact Assessment. A TO creates a common place for measuring impact and minimizing value loss, which is a common occurrence in transformations.

- Coordination. A TO helps join forces across silos and functions, especially in highly interdependent areas. It also helps measure and manage scarce resources—including specific IT skills—to ensure the success of individual initiatives.

- Accelerated Development. A TO coordinates change management tools ranging from leader coaching to communication plans and organizational pulse checks.

- More Certainty. A TO ensures that a transformation is meeting its milestones and that participants are excelling in their assigned roles.

A TO alone can’t guarantee executional certainty. But without one, organizations are unlikely to achieve it.

Getting the Transformation Office Off the Ground

The initial period, when the TO is getting organized and starting to exert its influence, is crucial to any transformation program’s success—and it is very intense. The businesses and leaders involved in the transformation learn about the processes they will need to follow, and they offer input regarding how to fine-tune those processes. Most leaders have their own approaches to managing projects, which may include their own tracking systems, periodic team meetings, and occasional hallway discussions.

Unconventional project-management approaches are fine in normal times, but they don’t work during transformations, when individual initiatives and portfolios of initiatives require the cooperation of multiple departments and the careful use of scarce resources. Everybody needs to align on one way of doing things—using the same process, accessing the same tools, and following the same cadence for reporting and meetings.

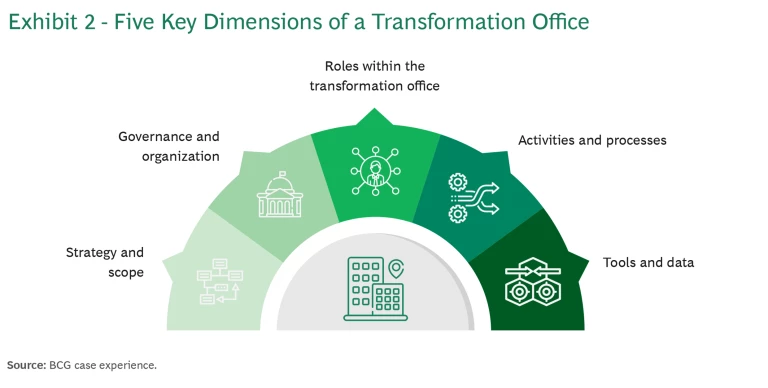

Five dimensions are essential to a transformation office. (See Exhibit 2.)

Strategy and Scope. The sponsor of the transformation program needs to be clearly identified from the beginning. Ideally that person will be the CEO or CFO, although transformations can work with another senior leader heading the TO if that leader has a clear mandate. One of the sponsor’s first jobs is to assemble a steering committee to oversee the program’s progress and make decisions quickly. Another key early task is to decide how activist the TO should be in driving the organization toward agreed upon goals.

A critical activity during this stage is to align the transformation’s financial targets with the organization’s existing financial systems. The company must identify the baseline—last year’s results, this year’s budget, or some other measure—from which to establish clear financial goals. This is an essential aspect of anchoring the transformation and allowing accurate measurement of value capture. Establishing clear financial goals also reduces the possibility of value leakage. Companies that aren’t diligent about this often encounter problems.

Successful transformations start with a big ambition, which the company then translates into a set of priority initiatives. The company needs to define and agree on what that ambition will be.

Governance and Organization. Having committed to a suitable ambition, strategy, and scope, the company should start to define the TO’s governance and organization. If it has never had a TO, the firm should begin by clarifying the role of the chief transformation officer (CTO) by pinpointing different leaders’ decision rights. Decision rights about strategic direction and objectives, of course, belong to the CEO. The CFO owns the financial goals, while the CTO should have decision rights over the company’s scarce resources, coaching responsibility, and the power to hold others accountable.

Other executives’ decision rights tend to be narrower, limited to activities within their own operating units or functions, which we call “workstreams” during transformations because of the many things departments must juggle. There are several ways to structure and staff TOs. In a big company, it is common for a TO to have 10 or 12 full-time employees. (See Exhibit 3.)

After establishing the TO, the company needs to integrate the office into its existing processes and operating systems. The organization must decide whether to use existing staff or build up resources to run the TO. This typically involves decisions about the type of external support that may be required. In our experience, it may also be useful to reexamine how the company normally handles processes. Processes that are often problematic during transformations and may require streamlining include the approvals needed for hiring and for adjusting the prices of products or services.

Roles Within the Transformation Office. The TO now needs to be resourced, which means making decisions about staff size and skill sets. Roles to fill include workstream liaisons, as well as staff to handle communications, finance, human resources, analytics, and digital and technology. The TO must also define its actual change delivery approach. A TO employee must work with the different initiative owners to figure out what operational elements, such as training and communication, those projects require. If the expertise needed for an ambitious change program doesn’t exist in house, and the right people for the roles aren’t on staff, third-party support may be necessary.

Activities and Processes. In every transformation, it’s crucial to implement common working rhythms, routines, and processes. This may seem obvious, but the devil is in the details, and devoting attention to this issue is tactically important.

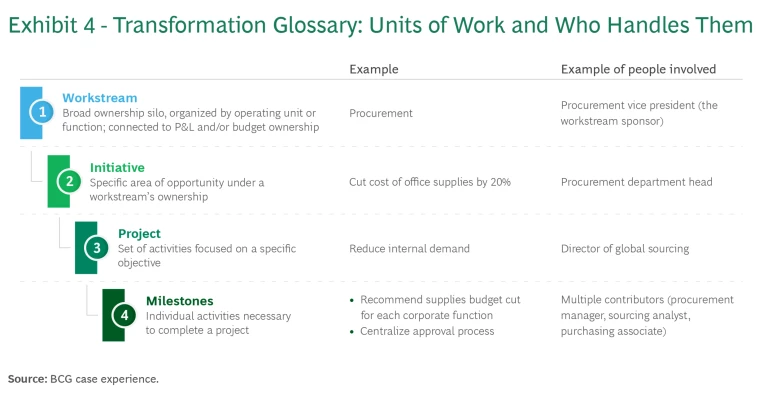

A common language can help differentiate among essential elements of the transformation. We commonly use a nomenclature that includes the terms “workstream,” “initiative,” “project,” and “milestones.” These represent the main units of work in a transformation, ordered from largest to smallest, and they follow a clear hierarchy. (See Exhibit 4.)

People are assigned responsibility for the different units of work, and—through a set of processes that the TO runs—begin to make progress toward agreed upon transformation goals. Two key processes are stage-gate methodologies and an accelerated meeting cadence, which are both discussed below.

Tools and Data. The fifth dimension of a successful TO involves the use of software and online tools. These are, in essence, tracking tools that link initiatives to financial outcomes (plans and forecasts) and impact assessments. It’s standard today to carry out this work in a digital impact-assessment center, for faster access to data and more holistic decision making. The pandemic has shown that these tasks can be handled virtually.

Transformation Voices: An Industrial Goods Executive on Working with Functional Leaders

I had one of my top HR people speak with each functional leader. It turned out that they were concerned about two things. First, why would we be doing this at a time when we had gotten back on a good growth path? And second, how it would it affect their individual agendas?

These questions made us realize that we needed a more fully articulated rationale. So, we took the next three weeks to talk it all through. That’s a lot of time to devote to meetings when you’ve already decided to do something. But it was worth it. The clarity in

the case for change that we developed made all of us more excited. And it allowed us to speak with one voice about what we felt we needed to achieve. When we went back to the functional leaders after this hashing-out period, it was much easier to get them on board.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Driving Financial Discipline in a Transformation

Financial discipline is a core component of a successful transformation. It encourages accountability and alignment. TOs must be clear about the financial goals of the transformation and hold the organization accountable to them throughout the duration of the program.

We recommend four steps to achieve financial discipline during a transformation.

Build a close connection to the finance team. TOs should prioritize creating a strong rapport with the finance function, and it should be built at the start of the transformation. The TO should work to promote transparency with the finance team to ensure that information is shared freely. Best practices for building this connection include:

- Hosting a kickoff meeting between the two teams

- Creating a dedicated communications channel for team members

- Freely sharing necessary information with the finance team

Determine a financial baseline for the transformation. Companies undergoing a transformation need to agree on a clear baseline. Three types of financial data can help:

- The Past. Actuals for recent reporting periods.

- The Future. Budgeted or forecasted performance.

- Momentum Case. Financial outcomes if the transformation meets its goals.

In developing a baseline, the TO should seek to avoid three traps:

- Lack of Collaboration. Without an agreed-upon starting point, companies will lack clarity on cost reduction and top-line growth.

- Lack of Communication. If business leaders aren’t engaged in setting the targets or baselines, or those targets aren’t effectively communicated, they won’t understand the numbers and will reject them.

- Data Integrity. If data isn’t checked for consistency across different parts of the business, the baseline will likely need to be adjusted.

Once the baseline has been created, the TO and finance team need to agree on the figures to avoid miscommunication and confusion.

Agree on a tracking and validation approach. The TO needs to create a clear approach to collecting, tracking, and validating metrics and KPIs from relevant teams, including finance, throughout the life of the transformation. To standardize this approach across workstreams, TOs should take the following steps:

- Define the business case for an initiative. Validation of the business case will occur later.

- Establish rules for tracking and measuring impact. All workstreams should be using the same group of KPIs to measure impact and identify potential problems.

- Agree on an approach for validating the impact of initiatives. This will require close cooperation between the financial planning and analysis teams and the TO.

- Agree on a standard process for capturing non-financial KPIs. These non-financial targets are still incredibly important for the success of a transformation.

This alignment will ensure a consistent approach to tracking and comparing the progress and impact of initiatives.

Leverage tools and reports to control expenses. Tracking financial inputs across a large-scale transformation effort can be overwhelming. Interactive dashboard tools—BCG’s is called Key by BCG—can synthesize incoming data and flag areas of concern. These tools have many benefits:

- Creation of a monthly assessment of actual versus planned achievements

- A single format with data from multiple systems

- Visibility of data by initiative owner and category

- Forecasts by category using purchase order data and run-rate spending

- The ability to drill down to explore transaction-level detail to understand spending behaviors

Transformation Voices: A Management Services CEO on the Importance of Financial Tracking

We set up a dedicated TO that was in charge of managing all workstreams. The office oversaw the translation of our overall strategy into clear objectives. Each of those objectives had a scorecard with financial KPIs that the TO was tracking. The effort had a lot of initiatives, so having an office dedicated to tracking helped us make sure that we were delivering the value we had identified. The major levers of this effort were improving our revenue and balance sheet, so financial tracking was crucial to our success. Using this robust tracking approach, we were able to hit the ground running and implement significant cost reductions early in the transformation process.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.

The Case for a Robust Stage-Gate Methodology

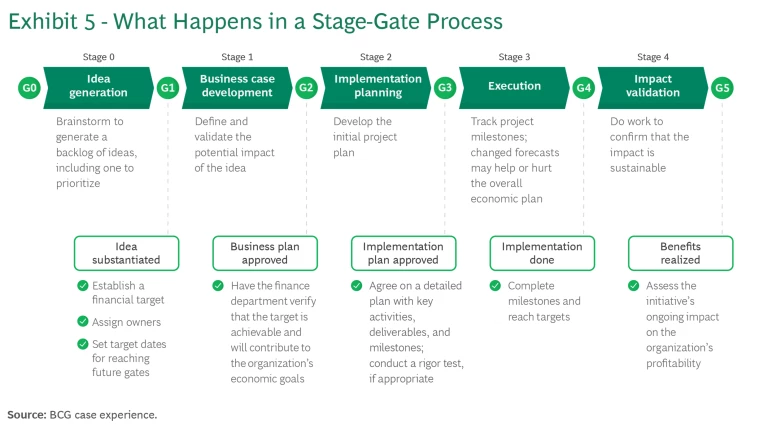

Every transformation follows a path from idea to execution. But no initiative involves just one idea and one execution challenge. Instead, each contains a constantly expanding set of ideas. The only way to manage them is to systematize the effort through stage gates. Stage gates ensure that projects move forward quickly and with regularly scheduled checkpoints to confirm that the original outcomes remain realistic.

Companies often downplay the value of stage gates, viewing them as a bureaucratic imposition that slows things down. To the contrary, a good stage-gate process speeds things up and keeps them on course. (See Exhibit 5.)

Consider the example of a household goods company whose transformation aims to increase profit through digitization and customer centricity. One of the firm’s initiatives is to handle the sale of frequently reordered supplies exclusively through its online channel. To help deliver this, the company has launched a project to ramp up its online pricing capability and offer discounts on online supplies during a transition period when both online and offline sales channels are still in use.

The core project team for this initiative consists of a product manager, the director of marketing, a regional retail liaison, an analyst from finance, and a VP of web development. At the idea generation stage, the team creates an initiative charter—a short description of the goal and how the team plans to achieve it. Stage 1 focuses on validating the business case—the ROI of the initiative itself and the eventual increase in per-unit profitability. If the project’s charter and business case withstand scrutiny, the team develops the key milestones of the initiative plan (stage 2), including the location, length, and goals of any pilot. If the initiative passes muster, it enters stage 3—execution. In stage 4, the project is reviewed to determine if all of its goals have been achieved.

Each stage plays an important role in strengthening the project. By the time it gets to stage 3, a project that began as a loose idea should have turned into an airtight plan.

The gates also contribute to the improvement process. At each gate, a group with a clear stake in the outcome looks at the work of the initiative team and decides whether the project is ready to advance to the next stage. Individuals with clearance authority at the gates may include the workstream leader, who is usually the head of the relevant function (sales, in this example) and often another executive. The TO plays a key role in facilitating the movement of initiatives across stages and ensuring that the transformation machinery is working efficiently.

The stage-gate approach requires significant work up front but provides four primary benefits that ultimately enable the overall transformation to run smoothly and deliver full value:

- Structure. The overall process creates structure and uniformity across a large and complex transformation. All initiatives and projects operate on a level playing field. The vetting process ensures prioritization of initiatives, ROI rigor, and smart execution plans with clear milestones before any project moves into execution.

- Transparency. The execution phase puts projects into active weekly tracking and monitoring, which creates transparency and focus.

- A Clear Metric. The stage-gate approach offers an explicit phase for measuring value delivery.

- A Way to Compare. The common language and process enables comparisons across the portfolio.

The stage-gate methodology works nicely for companies that are undertaking agile processes and leveraging tools such as objectives and key results (OKRs). While OKRs define what to do, the stage-gate process ensures that those things get done. The nature of the execution phase demands an agile mindset of quick problem solving and real-time adjustments. For all kinds of companies, agile methodologies—including concepts such as kanban and Scrum—can be helpful additions to the stage-gate approach.

Some Stage-Gate Best Practices

Several best practices can make the stage-gate methodology more effective. First, successful initiatives or projects have well-thought-out milestones that incorporate some sort of financial impact. Such projects do better than those without financial impact milestones.

This finding emerged from a BCG study of 20,000 data points related to transformation initiatives. The study, which relied on machine learning, showed that companies that make disciplined use of milestones have more success. Specifically, a lower and more manageable number of milestones correlates with project success rates that are 15% to 40% higher than those of projects that survey respondents thought had too many milestones.

Organizations struggle when they apply completely different impact metrics—for instance, profitability, sales growth, and customer satisfaction—to the same initiative. Too many measures for an initiative often confuses teams and gets them weighed down in determining which actions to take on all measures versus focusing on which actions are the most important. Our research shows that when initiatives have multiple measures, they are 40% less likely to succeed.

Avoiding the mistakes we identified in our study does not guarantee success, but the data highlights problems that organizations should avoid if they can.

A second best practice, done in the midst of the stage-gate process, is to undertake something we call a rigor test, which is basically a discussion conducted just before the execution stage that includes all of a project’s key stakeholders. Those performing the rigor test take a fresh look at the project—at whether its goals and milestones are reasonable and at how well its risks and interdependencies are understood. Rigor test discussions generally last no more than an hour, but they often expose some critical flaw: a milestone that has not been assigned or a dependency that no one has considered. After participants have addressed any flaws uncovered during this process, initiatives can move into the execution stage with a much higher likelihood of success.

A third best practice is not to allow initiatives to proceed without the finance department’s explicit approval of the business case (stage 1). Finance’s job is to assess the initiative’s likely profit or loss, one-time cost, and cash impact and to ensure that the project aligns with the organization’s broader financial requirements.

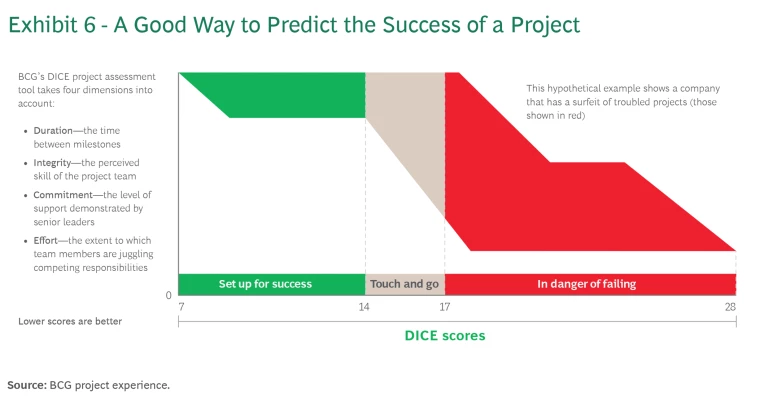

During the stage-gate work, successful transformation leaders assess the key success factors of their projects. This leads to a fourth practice, which we call DICE, that allows them to zero in on four factors: the duration between crucial milestones (similar to the rigor test); the integrity of the project team (including the extent to which the team has the necessary mix of skills); the commitment of senior management and the broader team; and the effort—over and above team members’ current commitments—that the undertaking requires. Projects’ DICE scores fall along a continuum ranging from “set up for success” to “in danger of failing.” (See Exhibit 6.) The CTO, a workstream leader, or the steering committee can use DICE at any point where it might be beneficial.

Companies need not dread the stage-gate process as a rigid methodology. Rather, they should embrace the process as a discipline that will help them do three things:

- Thoroughly vet each business idea or project

- Effectively plan and manage the development of new services and organizational changes

- Measure each initiative’s success

Transformation Voices: A Global Logistics CEO on Using the Right Metrics

Initially we were measuring only the individual dollar contribution from initiatives. After a few months, we also started measuring overall dollar outcomes. That is, we gave someone accountability for the ultimate economic result we wanted. We did this for the same reason that a person trying to lose weight gets on a scale once a week. Because that’s what really matters: the aggregate measure. The mechanisms for getting there—by, say, eating a specified level of carbs or eating only once each day—don’t make a difference if they’re not getting you to your goal.

This led to the second important adjustment: the introduction of a portfolio view, where we were able to monitor and manage the risks, benefits, and costs of the whole portfolio. The portfolio view helped us do a better job of prioritizing the changes we were making.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.

The Importance of Routines and Tracking in a Transformation Office

One thing that makes transformations so hard is that they require changing the behaviors of people in the organization. Regardless of how they operated previously, initiative owners in a transformation must be inclusive and transparent. They may have to adopt a fail-fast philosophy and align resources with other initiative owners. Eventually they are sure to encounter some new requirement that they won’t be comfortable with. The TO is responsible for ensuring that the changes happen anyway.

People further down in the organization must exhibit new behaviors, too. For instance, in a transformation that involves moving to multichannel distribution, a manufacturer’s retail store liaisons may have to enter their pricing changes into a central system and accept the need to collaborate with web colleagues.

The human element makes such changes hard. The very idea of change can create three specific internal conflicts that behavioral scientists have identified:

- Status quo bias is people’s tendency to favor the known over the new.

- Intention-action gap refers to people’s tendency not to do what they say they will do—and sometimes not even to do what they intend to do.

- Loss aversion is people’s tendency to fear failure more than seek success.

One or more of these behavioral norms exist in all of us. They explain one of the most common complaints that can arise during a transformation: that a key leader isn’t committed or isn’t taking the process seriously. Everybody is counting on that person to deliver something, and it’s not getting done.

In addition to problems of individual adjustment and acceptance, a host of top-down problems are common in transformations, most of them caused by two fundamental issues:

- Desired behaviors aren’t clearly articulated, so people don’t know what is expected of them.

- The business context isn’t reinforcing these desired behaviors.

People tend to act rationally within their business context. So if a behavior that should be happening in an organization isn’t, it’s generally not the fault of the employees.

In the past, we have written about how organizations can eliminate problems in their business by reducing complexity. But even after a company has improved its context, inertia can discourage people from operating differently. A framework we call ATAC can help activate desired behaviors. ATAC has four main components:

- Anchoring keeps the organization focused on the transformation’s main objectives and ambitions. It requires some kind of metric, often a financial one. Good TOs continually ask about progress toward achieving these metrics. This ensures that the rest of the organization gets the message.

- Transparency encourages behaviors that align with the main transformation objectives. It provides visibility throughout an organization, including at lower levels. Companies can promote organization-wide transparency through dashboards, checklists, personal check-ins, and more.

- Accountability makes each individual responsible for expected behaviors throughout a transformation.

- Consequences keep the transformation on track. When a goal is unmet or staff members underperform, management provides support and performance coaching. When appropriate, consequences can be positive, in the form of celebrating success through verbal praise or tangible rewards.

The tools that a TO uses to adjust the business context during a transformation aren’t revolutionary but rather the basic tools of organizations: meetings, decision rights, tracking protocols, and other enablers of transparency. But when a good TO uses these tools with sound judgment and discipline, it can create a powerful impetus for new behaviors and can set a transformation up for full success.

There’s no such thing as a glitch-free transformation. Even in a well-run program, 20% of initiatives won’t achieve their desired impact, and even more (30%) will typically be at risk. If all of the initiatives in your tracking system are proceeding perfectly, you’re not aiming high enough.

Tracking minimizes problems. In weekly or biweekly meetings, the TO brings together the owners of each workstream to discuss the status of their initiatives, projects, and milestones. In a best-in-class transformation, the TO doesn’t wait until the end of the process to see whether initiatives will meet their goals. Instead, it continually engages the workstream owners. This creates opportunities for agile problem solving and for pivoting to maintain momentum and reach key targets.

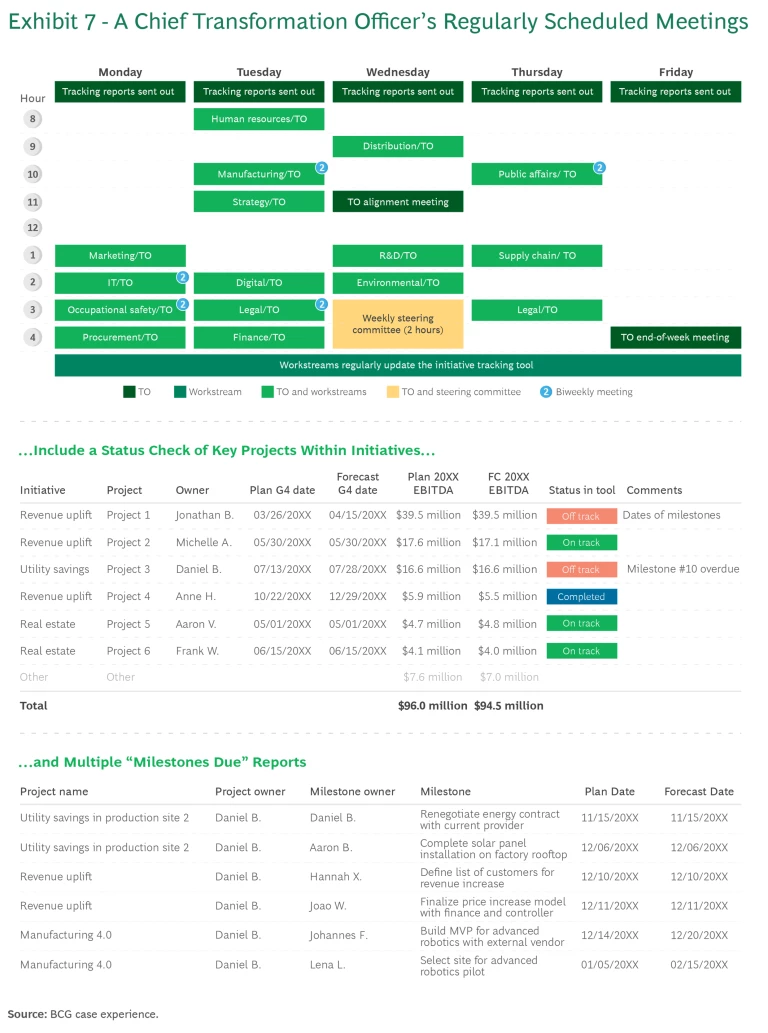

An effective CTO will assemble the heads of different departments—operations, finance, production, marketing, and human resources—to break down silos and push members to work together. In addition, he or she will schedule weekly steering committee meetings to make the decisions that no one else can. (See Exhibit 7.) To underscore the transformation’s importance, the program sponsor (CEO, CFO, or other top leader) should attend these weekly meetings.

The meeting cadence is intense—by design. A transformation isn’t business as usual, and it shouldn’t feel that way. At least initially, the program should make the people involved feel a little uncomfortable. A TO may even want to lean into the intensity, issuing “half the time” challenges to initiative or project teams to shock them into thinking in radically new ways. In many organizations, increased pressure works. Initiatives with shorter periods between milestone deadlines and faster impact updates see a boost of between 5% and 15% in their success rates.

Project and milestone owners need to know that the TO is counting on them to make progress every day, and they should also know at the end of each week’s meeting what they need to achieve for the next week. At the same time, meetings give participants a chance to identify and remove roadblocks. This often requires decisions and follow-up actions by higher-level executives. Indeed, transformations often “flip the pyramid,” forcing executives to solve problems for people one, two, or three levels below them.

“Nowhere to run, nowhere to hide—and no one to blame but yourself,” is the way one executive put it to us, at a point when he was just starting to understand what his company’s transformation would demand of him.

It’s a little bit like what happens when you sign on with a personal trainer. Initially, the workouts are beyond your ability and it’s frustrating. But with progress comes confidence and greater trust in the process.

Well-run TO meetings follow four best practices:

- They focus on cross-department problem solving. In a transformation, the biggest opportunities inevitably require cooperation across functional boundaries. A good TO helps different functions understand what they have to gain by collaborating. By emphasizing what’s optimal for all participants, the TO increases managers’ trust in the process and allows the CTO to emerge as one of the leaders of the organization.

- They maintain a bias toward working sessions. “They’re killing us with all these meetings” is a common complaint in organizations, and the risk that people will feel overburdened increases during transformations, with all the newly required touch points. A TO can reduce this feeling by making it clear that the focus of most meetings will be the centralized data system, which contains the status of milestones and other important data—not newly created PowerPoint decks. Indeed, prior to each meeting series, the TO should hold an initial meeting whose agenda should be the content of the weekly meetings, with special attention paid to the transformation’s nomenclature (as illustrated in Exhibit 4) and rhythms.

- They set aside time for encouragement. The TO should devote portions of some of its meetings to personal interactions such as a daily moment of encouragement that recognizes a key accomplishment either organizationally or by a specific member of a project team. The process for this can be short and simple, but it can go a long way toward keeping people motivated.

- They have tools to support the process. A crucial part of the transformation is simply having the right reporting tools, so people can access information in real time. The most important tool is software for tracking each workstream’s initiatives and projects and for creating a portfolio view. Each project should have a charter developed at the initial idea generation stage, as well as a business case and milestones. When the software highlights these three elements, the contribution that each project is making to the full transformation becomes easier to see. This is the portfolio view. For smaller transformations, companies may be able to make do with simplified tools such as Excel and Microsoft Project. But in our experience, bigger programs—and ones that integrate financial insights—usually require purpose-built transformation software. For our clients, we recommend using Key by BCG. The best-managed transformations also have an impact center, which pulls in details from a system like Key and reports from other parts of the company (whether sales or other performance indicators) to help the TO team understand the full picture.

Collectively, these routines help TOs reinforce the rigor of timeliness, the need for speed, and the importance of achieving objectives. Ultimately, they build trust as people in the organization see the value being created, understand required behaviors, and take more ownership and responsibility for their work. When leaders and contributors throughout the organization see projects paying off, they become advocates of the new way of working.

Transformation Voices: A CTO on the Need to Track Progress on a Single System

If I were to do it again, I would insist on one unified approach. Any initial pain would have been more than compensated for by the reduced workload thereafter, when there was just one system. Also the ability to steer the transformation and integrate it into a single story would have been so much easier. Next time I’ll know better.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Create Momentum for Change and Shift Your Culture at All Levels

Transformations are unlikely to succeed without a focus on culture and change management. People are often resistant to change. Culture and change management can overcome that resistance and help build new behaviors and processes into the organization. This step brings the “how” of transformation to life through concrete activities that encourage and reinforce behavioral change.

The TO should track this work to ensure that it has the same transparency, accountability, and focus as the other workstreams or initiatives. Culture and change management work can range from a training program for a sales team on managing pricing discounts to a company-wide communications program on the benefits of the transformation.

An Approach that Makes Cultural Change Stick

Culture and change management should be deployed at three levels of the transformation:

- The program level

- The workstream level

- The initiative level

The Program Level. Executional certainty requires changes in behavior that can only be brought about through cultural change. The TO needs to have staff that is dedicated to this by creating KPIs on staff engagement and other metrics. The office should then ensure the approach reaches workstreams and initiatives. There are three key elements to program-wide culture and change management:

- Desired Culture. When culture is defined as behavior, it is actionable and measurable and can drive performance. The best way to change behavior is through incentives. BCG takes a three-step approach to facilitating culture change: articulate, activate, and embed. Organizations need to articulate the desired behaviors, activate change leaders to model these behaviors, and ensure that they are embedded into the organization. The TO should help track progress when it comes to these three steps.

- Leadership Enablement. It’s critical to equip and unify leaders to spearhead the transformation program. The TO should track work that both motivates leaders and holds them accountable.

- People Engagement. Transformations mean more work for employees, who are asked to go above and beyond their normal duties. The TO must ensure that employees aren’t burning out by designing motivation tactics, helping them balance workloads, and offering them the new skills they will need. Retention can be a major issue during a large-scale change so the TO needs to think critically about how to keep the workforce informed and engaged.

The Workstream Level. The TO should work to ensure that culture and change initiatives are present in each workstream, provide support to the leaders of those initiatives, and hold those at the top accountable.

These initiatives should support the transformation efforts that are happening within the workstream. The following questions can help:

- How are workstreams simplifying and setting priorities to focus on the highest-value initiatives?

- How are workstreams establishing, tracking, and maintaining clear and measurable goals and metrics?

- Are your teams equipped with the resources and tools they need to be successful?

- What communication plans will ensure that messages are clear, transparent, and consistent?

- How are workstreams making sure that all members of a team are being heard?

The Initiative Level. All initiatives need to meet culture and change milestones to solidify behavioral change, and the TO should not allow them to proceed until that has been achieved. These milestones can take many different forms:

- Rewards for exemplary performance above targets

- Pulse checks on acceptance to change

- Surveys to surface and agree on new initiatives

- Training for stakeholders

Transformation Voices: A CEO on Facilitating Culture and Change

During our transformation, we focused on shifting the context of the organization to allow our employees to meet the performance goals we were setting. We used these contextual levers to shape a new culture that encouraged employees to take more time with customers or find efficiencies when possible. This behavior change then allowed us to meet the more challenging goals of the transformation.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.

The Transformation Office’s Role in Issue Resolution and Problem Solving

Imagine an ambitious transformation three or four months after it has begun. Senior leadership and the board of directors have approved the program’s targets and shared them with investors. The TO is in place and has met with the workstream and initiative leads to help translate a large, complex undertaking into an expansive portfolio of projects, each with its own charter, owner, business case, and milestones. The projects have been loaded into a transformation management software program. The TO has created a schedule of reports and touch points to keep things on track and enable teams to meet targets. Now it’s time for execution and delivery.

Although countless activities are going on, senior leaders, including the CTO, will focus primarily on a small subset of these. (Even a giant multinational company must narrow its main focus to 20 or so make-or-break initiatives.)

Some of these projects will exceed expectations and internal forecasts. Others will experience delays or fall short of expectations. If too many high-value initiatives fall short, the whole transformation will underperform. A good TO minimizes the number of missed targets during a transformation by doing the following:

- Creating processes—such as stage gates, DICE, or a similar TO assessment mechanism—that identify issues early

- Flagging the most important issues up the leadership chain to the CEO if necessary

- Encouraging stakeholders to resolve issues quickly or to rethink the initiative if no quick solution is available

- Paying special attention to critical projects that are off track

- Dealing with interdependency failure points

- Helping to reprioritize projects when disruptions occur

Without a TO, companies’ attempts to resolve issues can suffer from a failure of many cross-functional initiatives, with no one available with the authority to break a tie. A simple idea that we call “boomeranging” can help. Boomeranging ensures that non-executive staff can circle back to those with decision-making authority whenever they need to—thus increasing the odds that operating decisions will be made quickly and based on facts. Steering committee members are often part of the boomerang in successful transformation programs, whether it’s explained to them using that metaphor or not.

Let’s look at three of the most common issues that threaten transformations and see how they can be avoided or addressed.

Issue: Critical initiatives or projects are shown as being on-target (green) in transformation reports and meetings, but in reality they aren’t.

Potential cause: Off-track initiatives may be seen as failures rather than as opportunities to refocus and adjust. This leads to grade inflation—lots of green lights and very few yellow or red lights.

Potential solutions: The organization must clarify that it is aiming high. It should remind transformation participants that having high ambitions means that some projects and initiatives won’t be where they are supposed to be at any given time. Indeed, for a transformation to have a chance of full success, a certain number of projects should have a 50% or 60% likelihood of success (versus 95%). A good TO will communicate this explicitly, with the CTO emphasizing that the organization’s objective isn’t to have a portfolio consisting solely of projects that show up as green in the tracking system.

Demonstrating support amid temporary underperformance and missed goals isn’t the only way to encourage risk taking among initiative owners and project leaders. Organizations can also adjust certain contextual elements, such as how they handle performance management and how they think about financial rewards (de-emphasizing flawlessness and putting a higher premium on engagement, for example). And they can adjust their funding mechanisms to reinforce the point that a project’s current color in the traffic light schema is only one of the factors that will determine the level of investment it should receive.

Issue: The overall forecast for the transformation program is falling short of the target.

Potential causes: Important projects are underperforming, and there aren’t enough high-performing projects to compensate. Or the first wave of projects that entered the execution phase (stage 3) is concluding, but there aren’t enough second-wave projects waiting in the wings.

Potential solutions: Value slippage is extremely common in transformations. To manage it, the TO should ensure that finance team members constantly work with workstream leaders and initiative owners to assess their value forecasts. The most important number to look at in each case is the workstream leader’s overall target, not the performance of specific initiatives.

Take the example of a cost reduction effort that a global head of operations is running. Five big initiatives may be associated with this effort: automation, outsourcing, renegotiation of supplier contracts, management de-layering, and a reduced manufacturing footprint for the organization. The numbers could show that all of these initiatives are on track to produce their expected dollar savings. But cutting costs in one part of an organization can increase costs or create new ones elsewhere. So it is critical—with the finance department’s help—to forecast what the company’s run-rate costs will be after the changes are in place.

This highlights another key role of the TO: transformation portfolio management. Although transformations often take place over 18 to 36 months, most individual projects can be executed in two to four months. As projects reach completion, the company needs to replace them with new priority projects. The TO helps workstream owners ensure that they have the right balance of projects in development (stages 0, 1, and 2), in execution (stage 3), and in impact validation (stage 4).

Issue: Something unexpected happens that requires a sudden course correction in the transformation program.

Potential causes: A major disruption may result from some external factor, such as a new CEO, a financial downturn, or a regional health or environmental crisis. Indeed, during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, some companies in the midst of transformations experienced such dramatic drops in demand that they had to decide which parts of their transformation programs to maintain.

Potential solutions: When a disruption occurs, a TO can leverage the change process and program that is already in place. One inspired example of this involved a client facing a liquidity scare during the pandemic. The company had to switch quickly to initiatives with more favorable cash flow and away from many original initiatives that were designed to maximize EBITDA. They managed to move quickly because the work they had already done for each project covered cash impact. With the finance team’s help, the TO identified cash-consuming projects that needed to be put on pause and holding-pen projects that offered immediate cash flow benefits. Had the TO not developed properly vetted business cases at the outset, its response to the disruption would have taken much longer.

The larger point—relevant to any kind of disruption—is that the CTO and the TO need to have the tools to organize an agile response to many problems and disruptions that can occur during a transformation.

Throughout the process of a transformation, a good CTO and TO should actively identify problems, work with owners and leaders to solve them, and keep the whole program operating on schedule. On a day-to-day level, the CTO functions a bit like the coach of elite Olympic athletes. Such athletes benefit from being pushed and challenged—and so do many talented organizational leaders. Just how far can they stretch? The CTO earns the right to find out by demonstrating skill at problem solving and by obtaining needed resources. Although the CTO isn’t the one who stands on the podium and collects the gold medal, he or she is at least partly responsible for what the people in the organization achieve.

Transformation Voices: A European Bank Executive on the Value of Stretch Targets

Over time, however, the pace became slower and the results less impressive. Quite a few initiatives began falling short.

I realized that I needed to dig into the initiatives more deeply, to really challenge whether they were set up to achieve the goals we had. Basically, I was identifying “watermelons.” That was our term for the many initiatives that had a green status when looked at from the outside but turned into red lights everywhere when we dug into them. Whether because of inadequate resources or insufficient ambitions or some other problem, these were projects that shouldn’t be moving forward.

Sniffing out watermelons became my new hobby. It did not make me a popular man, but it was necessary.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Making Transformations Work for the Long Term

The changes at the start of a transformation are rapid fire and stress inducing, but those first few months are also when a transformation’s benefits are most apparent. This is partly because leadership teams initially focus on easy-to-execute projects to create buy-in and excitement and to accumulate success stories for use later when the going gets harder. We refer to the early phase of a transformation, which generally lasts six to nine months, as “funding the journey.” The company is both providing money and also expecting to generate cash from early projects that can be invested into later ones.

The big opportunities in transformations usually take longer to execute—18, 24, or 36 months. For instance, a company looking to reduce finance department costs could de-layer the organization to free up cash. Alternatively, the company could opt to automate or outsource part of the finance function to a low-cost country. Those projects would have higher payback but a longer gestation period.

Upgrading capabilities—for example, shifting an engineering organization from waterfall development to an agile approach—also takes time. Such an effort can be a gigantic value creator and a source of competitive advantage but is unlikely to bear fruit in the first months or even the first year of a transformation.

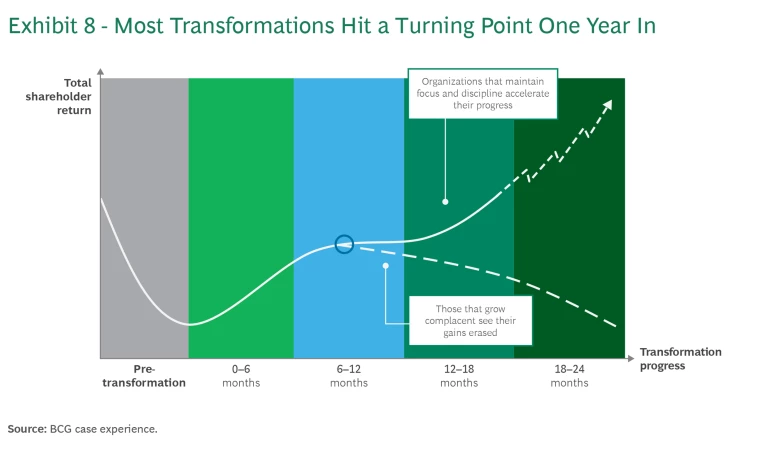

The next phase of the transformation is what we call the “medium term.” The transition to this part of a transformation is risky (See Exhibit 8.) It’s a time when the CTO must do three things:

- Replenish the pipeline of initiatives in stages 0, 1, and 2

- Ensure that the overall program retains its energy and that existing processes and routines maintain their power

- Take corrective action if the energy or enthusiasm of leaders or the broader organization begins to flag

Changes in Transformation Leadership

Personnel changes can complicate performance in a transformation’s medium-term phase, which is often when a TO’s operations are transferred from an outside consulting firm to the organization. This is a big transition. With good knowledge transfer and training (including job shadowing, in many cases), a transformation can keep its momentum. Otherwise, it can come apart.

Even a transformation that hasn’t included consultants and doesn’t have a moment of external-to-internal transition must weather significant shifts in personnel, since TOs tend to be temporary assignments. Having detailed documentation about how the transformation has proceeded is crucial. So is a well tend to have ample reserves of confidence and resilience—along with an aptitude for financial analysis and an obsession with details. They are also able to develop soft skills.

Transformations are like a multistage rocket launch: the liftoff gets most of the initial attention and causes the most nail biting, but the people in the command center never really rest. They know that the spacecraft will have to re-accelerate, adjust course periodically, and fire its rockets at the right time.

In a space mission, you’d never see a mindset of “Everything is going great—we can coast a bit.” There’s always another thing to do, a new way to ensure or improve an outcome. The same is true in an organization: when things are stable and running well, a transformation is poised for reinvigoration.

Nonstop Transformation

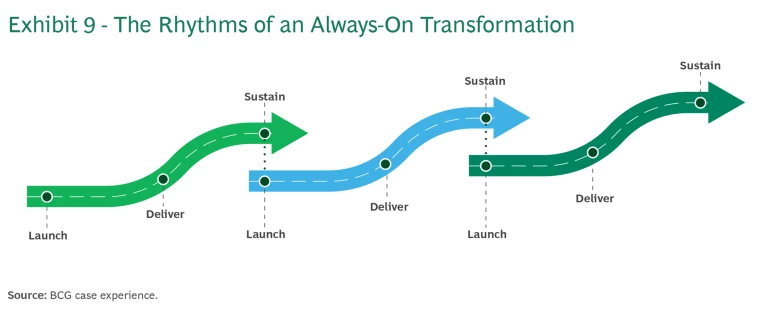

A company that has established a TO and is happy with the results may eventually ask, “Why would we dissolve this function?” Most such firms are in fast-changing industries and have everything riding on three or four major new initiatives in any given year. The role of the TO at these organizations is to ensure that the company executes future initiatives with the same rigor and process discipline displayed in earlier transformation-related projects. It’s about executional certainty and speed—and about turning agility into a competitive advantage. (See Exhibit 9.)

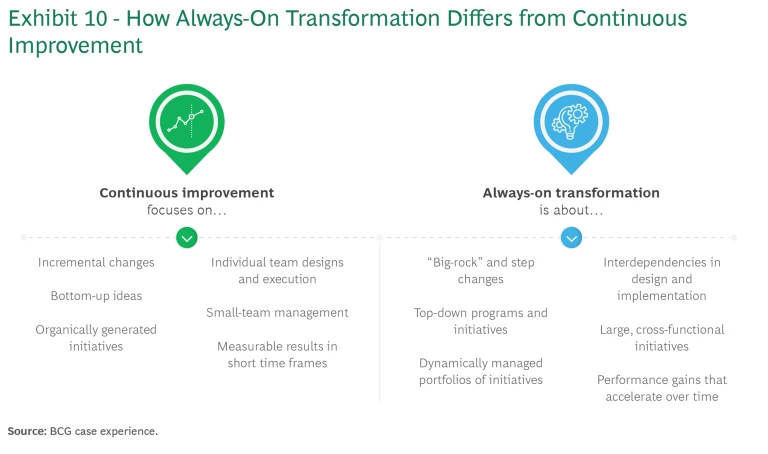

In a company engaged in always-on transformation, the TO becomes part of the organization’s management operating system, joining disciplines such as finance, performance management, and strategy. The TO has a highly targeted role at these companies: to focus on the company’s step-change initiatives and on its “big rocks.” This differs from continuous improvement, although that is important, too. (See Exhibit 10.)

Not surprisingly, some companies make strategy and transformation part of a single executive’s brief. Strategy informs what’s in the pipeline, and the TO ensures its execution, so one person oversees both things.

Transformation Voices: A Retail CTO on the Constant of Organizational Change

We had a succession of meetings in which we struggled to come up with a future state we could all agree on. And then, in one meeting, our CFO said, The only thing that is sure about our future is that we will have to continue to change once we have achieved it. We all recognized the truth of what he had said, and it shifted our focus from what we would become to the skills we would need to build. This reduced the anxiety significantly, as we could finally articulate the next level of stability for us: one rooted in our ability to keep changing, rather than our ability to operate a specific model. With that new focus, the idea of “always-on” transformation—which is where we were headed—lost some of its scary aura.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Conclusion: Toward Better Transformations

Transformations are here to stay—and they will always be difficult. But our decades of collective experience and the survey work we’ve done to understand transformations have given us a clear picture of what they require.

Success comes down to a few key things. Manage your processes rigorously, and institute strong governance. Use a stage-gate methodology to maximize the value of your initiatives, and use software and data to keep those initiatives on track. Put a TO at the center. Perhaps most important, set the bar high—and then look for the right times, places, and ways to raise the bar. If your organization is struggling, this mindset of “never good enough” will help you strengthen it. If your organization is already good, the right transformation just might make it great.

The authors of the 2021 version of this article were Reinhard Messenböck, Perry Keenan, David Kirchhoff, Kristy Ellmer, Julia Dhar, Mike Lewis, Ronny Fehling, Gregor Gossy, Simon Stolba, and Connor Currier. We want to acknowledge their foundational work and to thank our many clients and colleagues who have also contributed to our collective understanding of transformation.

The authors would also like to thank the following contributors: Jim Hemerling, Christian Gruss, Tuukka Seppä, Allison Bailey, Robert Werner, Brittany Heflin, Andra London, and Isaac Gaynor.