Innovation in business is vital for growth and differentiation, but homegrown R&D is expensive, it can require talent the company does not have in-house, and it might take too long to produce results. That’s why established companies are intensifying their cooperation with startups and setting up a variety of innovation vehicles. These efforts offer a way to accelerate the transformation of the core business and build new revenue beyond the existing core with less risk than going it alone.

But if they don’t demonstrate measurable impact quickly, these corporate venturing activities can lose management support. Companies therefore need the right structures in place to help promising startups scale up fast to establish a market presence, become profitable, and contribute to the corporate parent’s financial and strategic targets. This is not easy, and few companies do it well. That is why BCG has developed a scaling playbook for venturing activities, which is based on our experience from more than 200 corporate venturing cases.

If they don’t demonstrate measurable impact quickly, corporate venturing activities can lose management support.

Seven Transitional Challenges

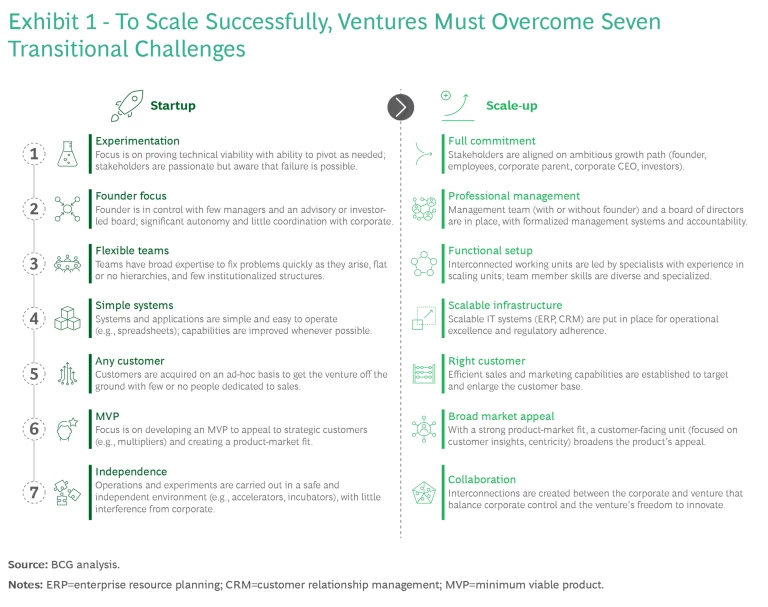

Corporates that collaborate with ventures can scale them in several different ways: create a partnership, become a minority or majority investor, incubate the venture internally, or create/acquire a venture and allow it to operate outside the corporate parent as an agile startup. No matter how they choose to collaborate, however, they’ll face seven challenges when transitioning from a startup to a scale-up (see Exhibit 1).

- Experimentation to Full Commitment. Startups are focused on proving their product‘s technical viability and will pivot their business model and/or product and services offering as necessary. A scale-up needs to have proven the technical viability, defined the product and stakeholders, and aligned on a growth path with the corporate parent.

- Founder Focus to Professional Management. In startups, founders are in the driver’s seat. The board is advisory or led by investors. But scale-ups need a formalized management system—and founders do not always remain part of the management team because new skills are needed for the next growth stage.

- Flexible Teams to Functional Setup. Startups tend to have teams with broad expertise and flat hierarchies. To become a scale-up, ventures must introduce interconnected working units led by specialists who have experience in scaling units.

- Simple Systems to Scalable Infrastructure. Startups typically use simple systems and applications to operate the company (spread sheets, for example). In contrast, scale-ups need more automated processes, more sophisticated IT systems, and the ability to leverage generative AI functionalities.

- Any Customer to the Right Customer. Startups often lack a formal marketing plan and will take any customer to get the business off the ground. But once a company has found its product-market fit, it needs to define its sales and marketing plan more precisely to acquire specific types of customers. Gaurav Srivastava, cofounder and chief product and technology officer of FarEye, an Indian-based logistics platform, said, “Our sales approach changed substantially [after we scaled up]. Now we think way more strategically. In the beginning we took every customer. We learnt to say no. We spend our customer acquisition costs more wisely.”

- MVP to Broad Market Appeal. Startups focus on creating a minimum viable product (MVP) that appeals to early adopters in order to develop a product-market fit. Scale-ups have already found a product-market fit and need to tailor the product to a broader customer base. Dimitri Sirota, the cofounder and CEO of BigID, a developer of software that helps companies secure customer data and satisfy privacy regulations, said the company initially focused on a few lighthouse customers to test its hypothesis before reaching out to a broader customer base to demonstrate the product’s sizable market.

- Independence to Collaboration. Startups often work in protected environments, such as accelerators or incubators, where they can experiment freely and independently. But scale-ups need to collaborate with the corporate parent, and this means introducing more controls and establishing interfaces and interconnections. Striking the right balance for effective collaboration is critical since introducing too many corporate controls and processes could impede the scale-ups’ growth. (In a previous BCG report , we outlined key success factors for collaboration between corporate and startups.)

Once a company has found its product-market fit, it needs to define its sales and marketing plan more precisely to acquire specific types of customers.

Navigate the Seven Challenges with a Scaling Playbook

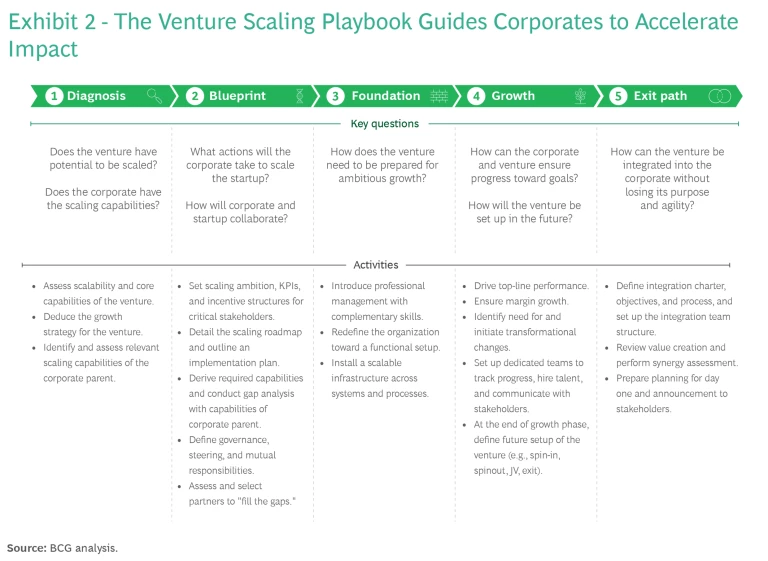

Over the past five years, BCG has worked on more than 200 projects with corporate venturing vehicles across the globe. In that time, we have identified best practices and developed a scaling playbook for corporate venturing structured to navigate the seven transitional challenges (see Exhibit 2).

Step 1: Diagnose the starting position.

Focus time and resources on only the most promising ventures for growth. By studying the venture’s business model and analyzing its capabilities and resources, the corporate parent can ascertain the venture’s starting position and potential growth path—such as expanding the customer base, entering new markets with the existing product, or developing new products for existing customers.

The corporate parent needs to assess which of its own capabilities can help the venture scale up. Are there enough synergies between its own capabilities and the venture’s business model to make collaboration worthwhile? “We are bringing startups into the SAP ecosystem that will become increasingly relevant partners for our customers. In this way we can provide SAP’s customers with additional innovation that complements SAP solutions that they can use out-of-the box,” said Alexa Gorman, SVP & global head of SAP.iO, the startups unit of SAP.

Startups that are ready to scale up generally share five characteristics: momentum, a strong team, customer focus, a unique selling proposition (USP), and a clear vision for growth.

Certain specific capabilities and resources will be unique to each venture’s growth plan. But startups that are ready to scale up generally share five characteristics: momentum, a strong team, customer focus, a unique selling proposition (USP), and a clear vision for growth.

- By momentum we mean that the startup has some traction in the market with customers and is already generating decent revenues. For example, when DHL invested in FarEye the startup already had relationships with several large customers and handled more than 500 million in shipments annually.

- Good candidates for a scale-up also benefit from a strong management team with a good combination of technical and business skills.

- Companies ready to scale also have an intense customer focus. Their ways of working are organized around understanding customer needs, tailoring products, and constantly seeking feedback.

- As a result of this focus, companies ready to scale have established a USP that satisfies the needs of their customers.

- Finally, potential scale-ups have a clear vision for growth that guides their activities.

Step 2: Create a clear blueprint.

After identifying the venture’s starting position and growth potential, the corporate parent and startup need to develop a blueprint for scaling the venture. This includes the overall ambition, specific milestones, the metrics to measure progress, what each side should contribute during the journey in terms of resources and responsibilities, and governance. The goals and timeline should be clearly spelled out and can, for example, be based on a mix of financial metrics (such as revenue growth, customer lifetime value) and strategic metrics (such as number of customers/clients, market share, number of markets).

As part of defining this growth path, corporate parents must agree not to interfere with the venture’s day-to-day business or its ability to adapt (perhaps in unexpected ways) as it pursues established growth goals. About You, a German online fashion retailer, and Otto Group, its investor, jointly agreed on a growth path and clear KPIs to measure progress. About You CEO Tarek Müller said, “It was important for us that Otto left us enough freedom within these financial guardrails to run the business.” Daniel Holth Larsen, portfolio director at DNV, a global risk management and quality assurance company and active owner of digital health software businesses, emphasized that corporate investors need to be patient, attentive to market risks, and allow for some levels of uncertainty.

When developing the scaling blueprint, the corporate parent and venture need to conduct a capabilities gap analysis to identify the capabilities the venture has and those the corporate parent will provide. This gap analysis will also likely identify capabilities that neither side has, which will need to be sourced from external partnerships or other means.

Corporate investors need to be patient, attentive to market risks, and allow for some levels of uncertainty.

All elements of the scaling blueprint—tracking KPIs, stakeholder alignment on progress and milestones, providing capabilities—require clear governance and division of responsibilities. Ideally, the corporate parent will have strong governance practices in place based on other venturing relationships. This includes securing support from management of the core business. For example, Emmanuel Cassimatis, the Europe, Middle East, and Africa partner at SAP.iO Investments (aka SAP.iO fund), said, “An important part of our work is to establish the connection and create the momentum with key business, product, portfolio strategy, and partnership stakeholders within SAP who become both the sponsors and recipients of the relationship and ROI.”

Step 3: Build the foundation for ambitious growth.

Once the blueprint is created, the corporate parent and venture need to put the actual structures and processes in place to enable scaling. We suggest two steps to build the foundation:

First, ensure the organizational setup promotes accountability and productivity. This includes defining roles, mandates, and accountabilities and setting up functional working units and shared services units. The corporate parent and venture also need to implement performance management through KPIs and a reporting system; appraise processes and career paths; promote corporate culture and ways of working; and define how the venture and corporate parent will interact regarding things like processes and governance (without interfering with day-to-day operation or crimping the venture’s ability to adapt).

For example, Johan Folkunger, CEO of DNV Imatis, a Scandinavian provider of software and information technology for the health care industry, emphasized that “the corporate really helps us by eliminating our need to build up some functions ourselves,” such as legal.

Startups need to jettison the bespoke processes and procedures used while bootstrapping the venture and adopt modularization and standardization to handle higher volumes more efficiently.

Second, startups need to jettison the bespoke processes and procedures used while bootstrapping the venture and adopt modularization and standardization to handle higher volumes more efficiently. For example, early on FarEye adjusted its logistics platform to accommodate how each client was distributing its goods. Over time, however, the company learned shipping best practices in each specific industry and can now recommend standardized solutions to new clients it can implement faster.

Step 4: Drive growth.

To actually drive growth, the corporate parent needs to make all necessary resources available to the scale-up (such as assistance in hiring talent, access to clients), regularly review the growth strategy and, when necessary, revise it. To this end, we recommend setting up dedicated teams through two offices:

- A scaling and communication office oversees the scaling process, tracks milestones and achievements, acts as a gateway for decisions, and maintains the link to the corporate parent to ensure alignment.

- A change management and capability building office identifies required capabilities along the scaling process and hires new talent, is responsible for ensuring transparency and project communication to employees in both the venture and corporate, and prepares the integration concept if necessary.

Step 5: Consider the exit path.

Near the end of the scale-up stage, the corporate parent and venture need to evaluate the scaling effort and decide on their future relationship. There are several possible exit paths, which will depend in part on how they’ve chosen to collaborate: integration of the venture into the business unit or the venture team into the functional unit (see “Ensuring a Smooth Integration”); creation of a standalone unit within the corporate parent; a spinout of the venture so it’s a standalone business outside the corporate parent (though still owned at least in part by the corporate parent); reduce ownership share and involve other strategic partners; or divestment, which could mean a sale or “killing” the venture if it’s not been successful and divestment is not possible.

Ensuring a Smooth Integration

- Define key activities and milestones for the integration. Ensure buy-in and commitment from the business unit that is integrating the venture.

- Create a dedicated integration team working closely with the business unit, making sure to define leadership, reporting processes, roles, responsibilities, and guidelines for recruiting members of the integration team.

- Assess synergies, create synergy targets and identify the key risks to a successful integration.

- Prepare a day-one announcement and communication plan for external/internal stakeholders, including retention packages to keep valuable talent.

- Continue to address the seven scaling challenges over the long run to keep the venture growing.

- Have a postintegration growth plan that both parties align on beforehand, including what to achieve, by when, and what it requires from both sides.

- Ensure that venture leadership and critical talent stay on board and are motivated to push further.

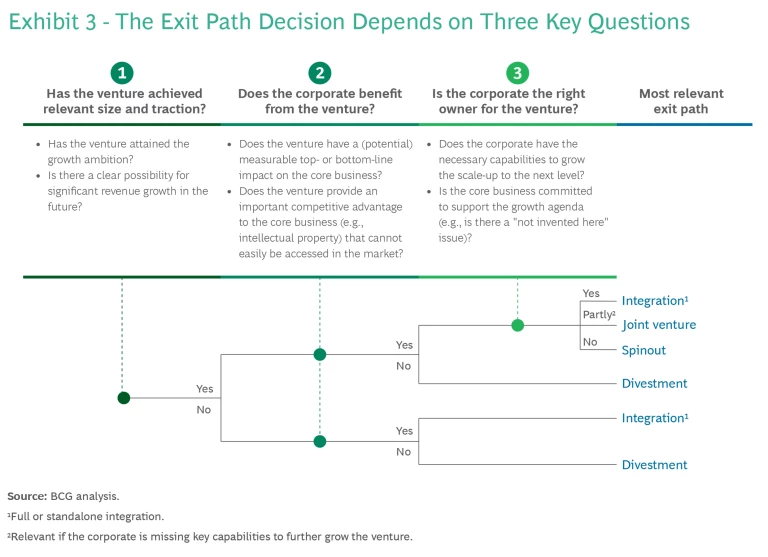

The decision about which exit path to choose should follow a clear rationale (see Exhibit 3).

Creating Beneficial Impact

More than ever, rapid innovation is critical to business success. But established companies often struggle to innovate and are wisely starting to engage with startups more often. Done right, corporate parents can use their expertise, scalable processes, and broad customer base to help startups become scale-ups—to begin cashing in on their momentum, strong management teams, customer focus, unique selling propositions, and visions for growth.

The challenges of moving from a startup to a scale-up are not inconsequential, and it’s critical that corporates engage with startups in ways that generate real impact quickly to justify the significant time and attention these relationships require. By following the venturing scaling playbook described here, corporate backers have a solid opportunity to accelerate a startup’s success and create real impact for their core business.

The author team would like to thank Michael Brigl, managing director and senior partner in BCG’s Munich office, for his contributions to this article. He can be reached at brigl.michael@bcg.com.