Environmental changes and extreme weather events are occurring with alarming frequency, creating severe problems for communities and economies. Over the past 15 years, climate shifts and weather events in the US have caused more than 7,000 deaths and more than $1.6 trillion in costs, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information. Yet many government agencies at the national, state, and local levels are only starting to recognize the magnitude of the challenges they face.

Confronted with competing political, societal, and financial demands, leaders might be tempted to sideline environmental and weather preparedness. But evidence derived from BCG research presents a compelling case for making adaptation and resilience a core component of strategic planning. Leveraging the experience that we have gained in our work with governments around the world, we have developed six steps that public sector officials in the US can take to build the resilience needed to stem the escalating human and financial costs, promote the stability of their economies, and enhance the safety and prosperity of their citizens.

People, Economies, and Resources at Risk

Environmental changes take a heavy toll on what governments are supposed to protect: people, economies, and natural resources. Extreme weather events cost lives and expose citizens to health risks such as excessive heat and waterborne diseases. They disrupt essential services such as health care, education, and communications. People may lose their jobs or be forced to relocate.

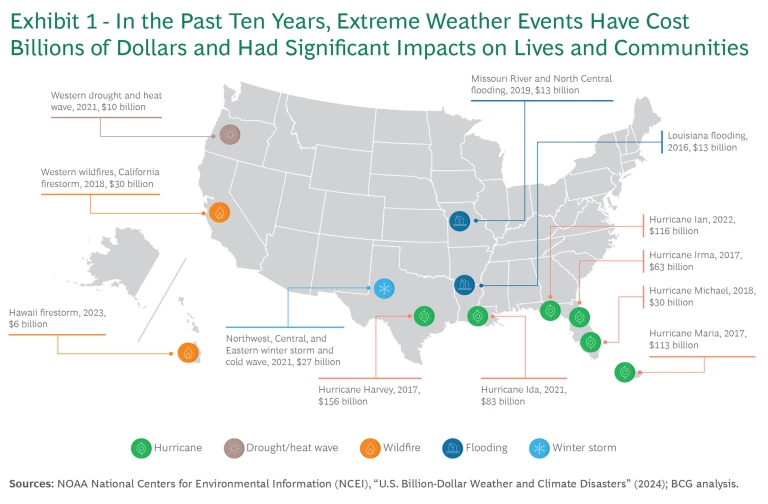

For example, in 2018, Hurricane Michael hit Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida, causing catastrophic damage to infrastructure and assets such as aircraft. The work of rebuilding this critical base (which is still ongoing) is estimated to cost almost $5 billion. That same year, Northern California’s Camp Fire—the deadliest and most destructive in the state’s history—destroyed more than 18,000 structures, resulting in total economic losses of $16.5 billion.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on the public sector

Catastrophic weather events and environmental shifts can also damage or destroy vital natural resources such as beachfronts, lakes, rivers, and forests, putting at risk the natural beauty that underpins tourism and disrupting supplies of essential raw materials.

But beyond catastrophic events, chronic and recurring environmental challenges—such as heat waves, sea level rise, and prolonged droughts—disrupt lives and dampen economic productivity. And these threats often disproportionately affect the most vulnerable and disadvantaged members of society.

In the short term, the economic burden of dealing with a disaster includes the cost of rebuilding and repairs. In the longer term, it encompasses such effects as reduced productivity and higher operational costs due to increased energy use during heat waves or periods of extreme cold.

The US may be better able to adapt to environmental shifts than less-developed and more vulnerable parts of the world. But it cannot escape their effects. And although extreme weather events are on a trajectory to worsen over time, the costs are already being counted. (See Exhibit 1.)

The Status Quo Leaves Worrisome Gaps

The US public sector at the local, state, and federal levels is not fully prepared to manage extreme weather events and to deal effectively with the impact of ongoing environmental shifts such as persistent heat waves and droughts. Indeed, many states and cities have no plans at all, although federal agencies typically have at least initial developed strategies in place. In many cases where plans do exist, they do not address how to implement strategies in practice, lacking budgets and operational roadmaps with clear goals tracked by key performance metrics.

Two additional weaknesses exacerbate the situation: the nation’s aging infrastructure and planners’ failure to consistently give due consideration to extreme weather in designs and approvals for new developments. Other obstacles include governance complexity, coordination challenges, and a dearth of comprehensive data.

The White House Office of Management and Budget estimates that climate impacts could cost the federal government $2 trillion annually by 2100. And beyond the economic costs, agencies risk losing public support as communities at the frontlines of impact belatedly blame leaders for failing to protect them from preventable harm.

With tight budgets and competing demands, governments must make smart, timely decisions to ensure that every dollar they spend delivers maximum impact. BCG research shows that by minimizing disaster losses, avoiding capital costs and lost revenues, and cutting operational expenses, a dollar spent on adaptation and resilience today yields a median future savings of 5 times as much and in some cases more than 50 times as much—all while protecting lives, livelihoods, and communities. (See “Adaptation and Resilience Levers.)

Adaptation and Resilience Levers

- Infrastructure measures, including protection against flooding or heat as well as coastal protection

- Energy measures, including decentralized generation, energy storage, and grid management and monitoring

- Water measures, including water collection and storage and water use monitoring and efficiency

- Health measures, including management of heat-related illness, injury, and mortality

- Community and business continuity measures, including disaster preparedness, supply chain resilience, and insurance

Making It Happen: A Six-Step Strategy for Public Sector Leaders

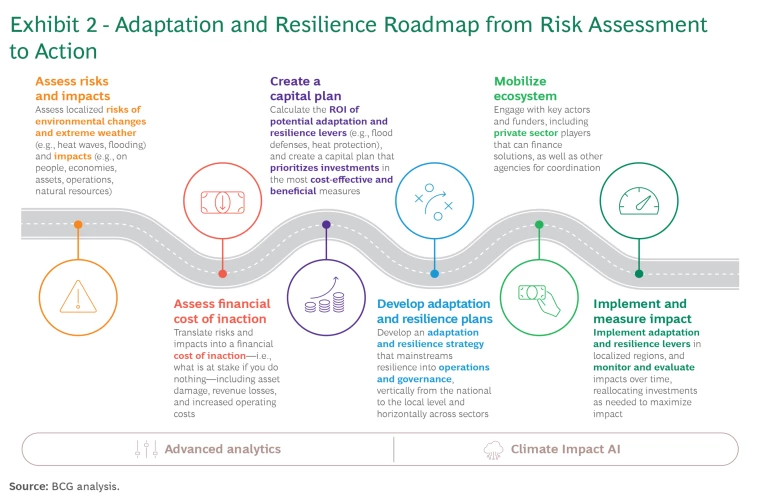

US leaders clearly need to be better prepared for environmental and extreme weather crises. From our experience in working with governments around the world, we have developed six steps that will enable US public sector leaders to move beyond risk assessment to create robust, actionable strategies and capital plans that will expand their adaptation capabilities and strengthen their resilience. (See Exhibit 2.)

Know your risk level and impacts. The first step is to map localized risks and vulnerabilities associated with extreme weather and climate threats, based on the geospatial position of your assets. By assessing the criticality of these assets and other competing priorities, you can identify the locations and assets where resilience measures are most crucial. Assessing tangible, measurable impacts—on citizens, the economy, assets, operations, and natural resources—will direct agencies toward the right solutions and provide the evidence needed to unlock funding.

For a densely populated coastal city facing flooding, for example, how many people could lose their homes or access to critical services such as health care, electricity, and communications? For the US Armed Forces, how might a heat wave affect operational readiness and productivity?

Evaluate the cost of inaction. Weather events inflict massive losses and damage, ranging from infrastructure harm, higher energy costs, and pressure on public health systems to revenue losses from reduced agricultural or manufacturing output, lower employee productivity, and reduced tourism. Although these costs are becoming more evident, the world does not yet fully comprehend their true magnitude. And beyond economic damage, weather events can have immense social and natural impacts whose precise dollar value is difficult to calculate.

Projecting these potential costs enables government agencies to compare risks, prioritize adaptation investments, evaluate returns, set budgets and investment timelines, and prepare for periodic catastrophic events and recurring challenges such as heat waves. Given the cost of inaction, the case for action is evident. There is a strong business case for investing because impacts are already happening—and in fact are worsening—and because proactive investment can often prevent much larger losses and worse damage going forward.

In addition to investing to offset future losses and damages, governments can highlight the potential upsides of adaptation and resilience, such as new jobs and revenue streams. For instance, investing in desalination plants can create new export industries around water technologies. Introducing regenerative agriculture practices can boost economic output and increase government revenue.

Create a capital plan. Adaptation and resilience project portfolios should maximize financial and socioeconomic return on investment—investing in the most impactful and cost-effective solutions. During heat waves, for example, a US agency with employees who work outside might shift away from midday working hours rather than investing in costly shade infrastructure. Solutions may include physical infrastructure, policy and process changes such as emergency response systems and crisis management capabilities, and technologies such as AI-based early-warning systems.

Environmental benefits are important considerations, too. Rather than constructing cement seawalls for flood prevention, a coastal city could deploy nature-based solutions such as restoring mangroves, which also foster biodiversity. Conversely, solutions should not exacerbate a problem. For example, a state facing drought should avoid water distribution strategies that deplete water resources in other areas.

Of course, no extreme weather or disaster plan exists in a vacuum. Governments must weigh these capital plans, integrate them into broader capital investment plans, and prioritize them appropriately. Fortunately, such investments often provide additional resilience benefits that align with government priorities. (See “Developing a Smarter Capital Plan to Adapt and Build Resilience.”)

- Develop adaptation and resilience plans. Governments should develop comprehensive, coordinated plans that operate vertically (from federal to state to local levels) and horizontally (through sector-specific strategies such as water resource management, infrastructure and energy resilience, wildfire risk reduction, and public health plans). Well-conceived plans will be measurable, milestone based, and adaptable as risk levels and priorities shift. They should also involve key members of the ecosystem in the planning process.

- Mobilize the ecosystem. US public sector officials should think beyond the planning stage to include execution. This means considering which public, private, and nonprofit elements of the ecosystem they can mobilize. By guiding the private sector—particularly companies providing critical public services, such as energy and communications—governments can harness corporate resources and capabilities to build adaptation and resilience plans that also protect the public sector and its stakeholders and citizens. Furthermore, to supplement their budgets, governments can tap into private finance for adaptation and resilience projects through such structures as public-private partnerships for infrastructure development.

- Implement and measure impact. Governments should monitor and evaluate the impacts of their adaptation and resilience strategies over time. Continuous assessment can enable agencies to identify areas for improvement and reallocate resources to meet shifts in environmental conditions.

Developing a Smarter Capital Plan to Adapt and Build Resilience

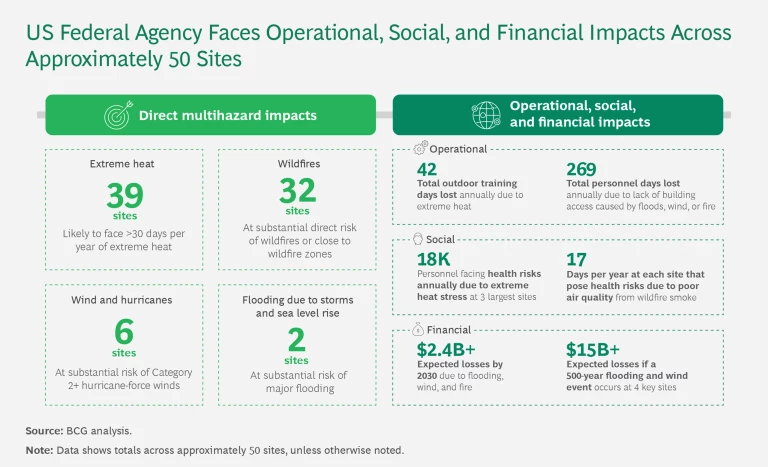

For example, BCG used its proprietary Climate Impact AI platform to assess potential risks and impacts at more than 50 government sites in Texas that are prone to extreme heat and wildfires or, in the case of coastal and riverfront locations, at risk of flooding and hurricanes.

Beyond risks to the government’s infrastructure, 8,000 employees could face health risks when working outdoors in extreme heat or in poor air caused by wildfires. For the agency, costs could include loss of outdoor training days and of working days when flooding, winds, or fire prevent personnel from accessing buildings.

Our analysis yielded a range of potential adaptation and resilience interventions, focusing on the agency’s highest-priority sites and optimizing spending on the most beneficial and cost-effective levers. (See the exhibit.)

Looking Ahead

As environmental changes and extreme weather become the norm, US public officials must ask themselves some hard questions: Are their citizens, economies, assets, and ecosystems at risk? What do the officials stand to lose if no action is taken?

The good news is that US governments now have at their disposal the data and tools necessary to assess risks and potential impacts. By accurately gauging risks, impacts, and the cost of inaction, while taking stock of existing adaptation and resilience measures, governments can develop a strategy that fits their budget and closes preparedness gaps.

Using these tactics, they can devise capital plans and adaptation and resilience strategies that will help them build a more resilient future. But with the next disaster just around the corner, they need to act quickly, before it’s too late.