Demand for green minerals is soaring–with game-changing prospects for the global mining industry. The market for green minerals, which include copper, nickel, cobalt, and lithium as well as other rare minerals, doubled from 2017 to 2022 and is set to double again by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Longer-term revenue outlooks vary, but all are staggeringly high, with some estimates projecting that green-metal purchases could reach $10 trillion by 2050 to meet global climate aspirations.

Longer-term revenue outlooks for green materials vary, but all are staggeringly high.

But the metals and mining industry will need to place big investments of its own to make good on these opportunities. In the next five years alone, the sums required to bring key minerals to market could exceed $400 billion. These are eye-watering sums. But mining organizations must fundamentally change how they approach strategic planning if they want to achieve the value creation potential these opportunities can deliver.

At issue is the modeling that many in the industry use—which often assumes that development timelines, operating performance, price, inflation, and other business case factors will follow conventional patterns. But everything related to the green transition is evolving rapidly, and very little about today’s trends conforms with historical patterns. New technological developments are emerging, policy positions are changing, and mining is increasingly in the political and public zeitgeist.

To ensure resilient growth and returns, mining leaders need to envision multiple plausible outcomes so they can make the most risk-advantaged decisions. This involves a very different type of planning.

Predicting One Year Out Is Harder Than Ever, Never Mind Ten

Just about every variable in the mining landscape has become more volatile. And sudden twists and turns in underlying fundamentals can have profound impacts on forward-looking returns. For example, the restrictions that China imposed on Australian coal in 2020 effectively cut off $15 billion in trade overnight.

Some might argue that such examples are exceptional, but disruptive events are becoming more persistent. Consider pricing, for instance. What assumptions should a steelmaker use for its ten-year investments, given that metallurgical coal has swung from about $50 per ton to more than $400 per ton in the past five years? Even bellwether commodities such as copper have seen the spread between high and low prices widen to 2.5 times benchmark levels over the same period.

Shifts in trade policy are also becoming more frequent. China, for example, has substantially decreased exports of gallium and germanium, minerals critical for chip production. These reductions could disrupt supply chains in multiple downstream industries. At the same time, policy shifts can open new growth vectors for miners—with an increasing number of countries striking trade agreements aimed at securing the supply of critical minerals and bringing more parts of the metals value chain onshore.

Regulatory uncertainty is rising in many jurisdictions as well, with resulting impacts on timelines and returns. It took ten years for one copper mine to go from late-stage engineering to construction as a result of changing guidelines—more than double the average time a decade ago. Other projects have been mired in lengthy permitting processes, seen prior permitting decisions overruled, or experienced budget-busting capital cost increases as a result of unforeseen externalities. Government expropriation and taxation can also materially alter a project’s returns. The government of Queensland Australia introduced a tiered windfall royalty on coal in 2022, raising the rate from 15% to as much as 40%, depending on price. In Chile, constitutional reform could lead to higher royalties as well. And, as has been well documented, Panama recently overturned mining approvals for a large copper mine, and government and company officials remain embroiled in an international arbitration process.

The pace of climate change is another disruptive force. The green transition could create (or destroy) trillions in value by 2030 . The sudden run-up in lithium pricing and associated revenue over the past three years is one example of the skyrocketing growth prospects that miners have enjoyed. With projected high rates of demand for many other metals over the coming decades, it is easy to see only upside. But rosy forecasts are far from certain. Automotive equipment manufacturers are still innovating electric vehicle design and battery chemistries, and their changes could impact demand significantly. Tesla, for instance, recently announced a switch to a 48-volt electrical architecture that uses thinner wires, a shift that some analysts claim could cut copper needs per vehicle by 75%. Anticipating shifts like these requires exploring alternatives to the consensus.

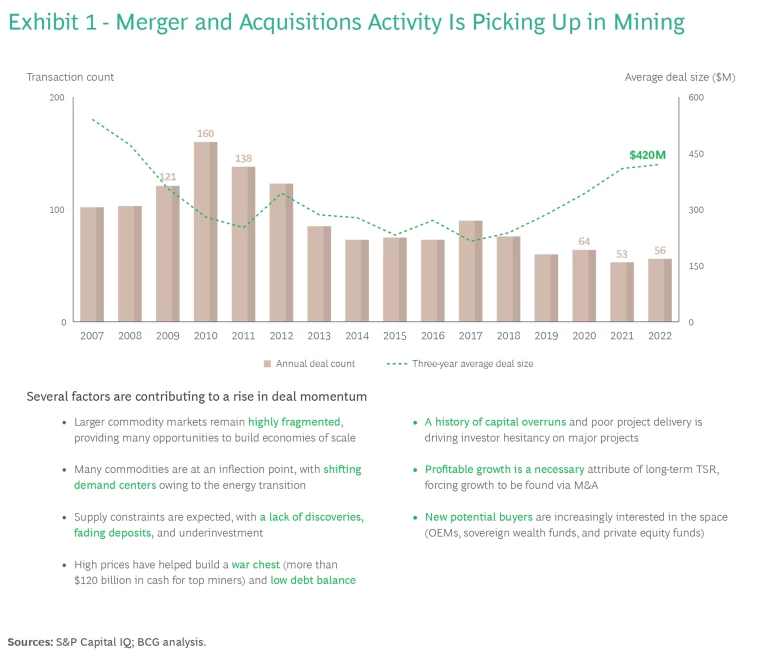

Finally, M&A is set to gather momentum across mining, fueled by several converging factors. (See Exhibit 1.) As leaders assess promising targets, they need to have confidence that such acquisitions will be value accretive amid this uncertainty.

So how should miners account for all this uncertainty?

Scenario Planning Can Help Miners Build a Resilient Future

Scenario planning isn’t new. The energy giant Shell has been using scenarios since the 1970s to support large company-making bets. Western military organizations use them to determine where and how to allocate multiyear defense spending. Sophisticated utilities use them to inform network planning investments. And municipal planning authorities use them to make land use designations.

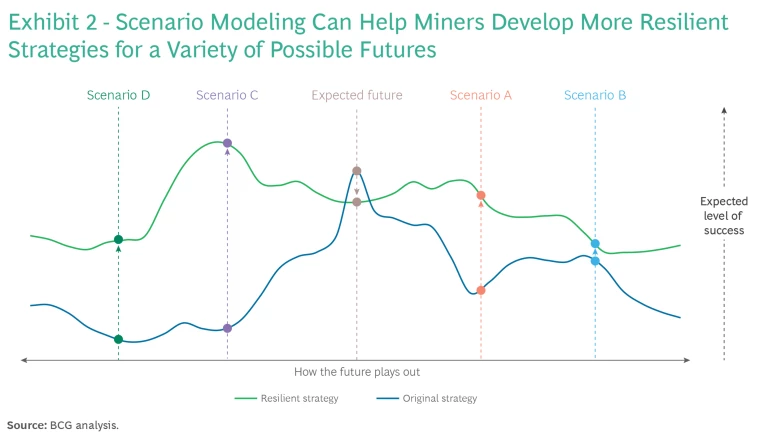

Unlike typical business planning, which often gauges how conditions will evolve according to a predetermined set of variables, scenarios force decision makers to develop multiple plausible futures by weaving a far more diverse set of risk factors, including potential shocks, into different permutations, then modeling the projected consequences. This approach gives leaders a methodical way to plan for uncertainty so they can design more resilient strategies and improve shareholder value. (See Exhibit 2.) One aluminum company has delivered shareholder returns 10 percentage points higher than its industry peers since it adopted scenario planning to aid with M&A decisions. And some BCG studies indicate even greater TSR outperformance for resilient companies during periods of turbulence.

No analytics, no matter how robust, can precisely predict the future. But businesses don’t require precision to act. Instead, they can monitor trends and use scenarios to

pressure test strategic choices against a diverse set of possible outcomes

. Teams that do this give their company an edge by creating the platform to act decisively when market signals change and by envisioning the capabilities required to succeed. Getting started involves four steps:

- Identify and prioritize material business uncertainties. Instead of examining one or two variables such as commodity prices and inflation, strategic planners need to consider a full range of uncertainties so they can develop a better understanding of many possible futures. Important variables to take into account may include global trade flows, climate policies, country-level regulations related to resource extraction, and the rate of technological development. While the exact number of factors to consider varies depending on the business case, there are typically six to ten.

- Generate potential outcomes. Planning teams should play out their research to understand how various trends might combine; then teams need to model the implications . Inviting divergent opinions to generate a variety of future outcomes is essential. For example, an economist in London is likely to have a different outlook on growth and carbon policy than a smelter executive in Lingbao.

- Group the outcomes to develop stretched but plausible scenarios. Organizations should develop four or five scenarios. (Any more starts to diminish the utility of the exercise.) They can create these scenarios by pulling trends and outcomes into logical groupings that allow team members to fully immerse themselves in a potential future.

- Assess strategic choices under each scenario. Teams should then consider which choices perform best across the majority of scenarios . Identifying these “no regret” moves enables miners to move forward decisively while preserving the flexibility to act on other value-creating investments when the conditions are right. Leaders can stress test these moves further using war gaming and contingency planning and by engaging individuals who have been removed from the core scenario development. These steps can bring fresh perspectives and additional resilience to the strategy without locking teams into a narrow set of actions.

Consider the example of a metals miner. An accelerated transition to a low-carbon economy could drive significant demand for green metals. Governments might expedite permitting and allocate increased funding for mineral development. Under this future, a miner might expect strong growth to justify investing in exploration teams and greenfield development. An alternative scenario, however, might feature a more disorderly, even chaotic, transition to net zero, characterized by rising eco-activism and new barriers to open-pit or high-water-use mining. Under this future, a metals miner would choose to invest in its existing operations (even if they are only marginally profitable today) and more aggressively pursue brownfield exploration. The company might, for example, look to secure rights to underground mining projects that are far from population centers and have lower water-use intensity while at the same time reducing exposure to open-pit greenfield opportunities. Both scenarios could result in equivalent internal rates of return and net present value projections, but the path to value in each case would require very different winning strategies.

Now Is the Time to Build a Resilient Future

Establishing a scenario-planning muscle requires miners to invest in new practices and ways of thinking. First, few mining companies have dedicated strategy teams, so most need to start by gathering a group of individuals who can think laterally and develop stretched scenarios that are in tune with the organization’s ambitions and constraints. These individuals also need to be capable of explaining the implications and embedding a resilience mindset more broadly.

Establishing a scenario-planning muscle requires miners to invest in new practices and ways of thinking.

Second, management needs to ensure that sufficient process discipline exists to signal which decisions merit discussion through the lens of scenarios. In our view, all strategic resets, M&A, project stage-gate or final sanction decisions, internal transformation investments, and material commercial commitments rise to this level. In some cases, large-scale talent moves or life-of-mine planning may warrant it, too. Processes to integrate scenarios into existing valuation and risk management processes are also important; for example, using scenarios to understand real option value (that is, the value of positions that give management the ability, but not the obligation, to act on a particular business opportunity or investment) would be additive to traditional capital allocation processes.

Third, cultural change is critical in fostering openness to new ideas. Forming investment committees or decision review boards with formally assigned roles similar to the “black hat” model prevalent in private equity contexts could help miners institutionalize this kind of debate in an emotionally safe way. They also need to elevate institutional learning, conveying the point that scenario analysis is different and more strategic than sensitivity analysis or conventional “high/low” business case assessments. Leaders need to ask: “Do we look beyond price, inflation, and interest rates to evaluate strategic options?” And “Do we deeply review investments through the lens of multiple possible futures?” If the answer to either of these is “no,” now is the time to use scenario planning to build resilience. Your shareholders will be grateful.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ross Middleton and Elan Code, whose input contributed greatly to the development of this article.