Investments in green sectors in Africa have grown significantly, despite persistent volatility and macroeconomic risks, but the gap in climate financing remains. If it can be filled, growth of green sectors can be accelerated. This is vital. Additional investment of $2.4 trillion is required until 2030 to meet Africa’s climate needs, but to date, only 12% of this funding has been met or committed.

Several levers can be pulled, both to accelerate the growth of green sectors and to increase the availability and affordability of capital.

Factors That Impede the Growth of Africa’s Green Sectors

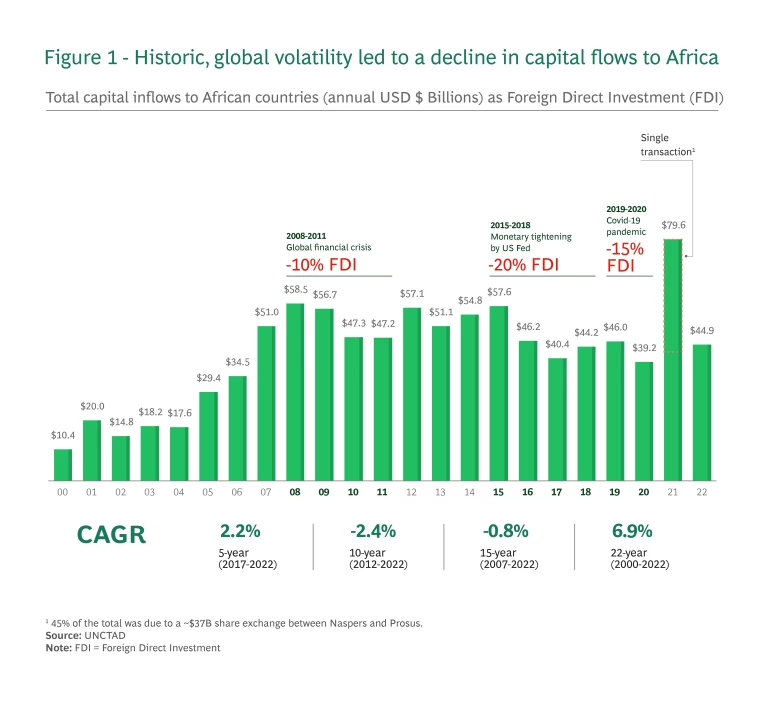

Most companies in the region rely on foreign investment to grow their footprint and impact, but capital inflows have been volatile. Green sectors are generally capital intensive and have long investment horizons (10+ years

Events such as the 2008 economic crisis and the 2016 US Fed rate hikes drove significant retraction of capital (-10% and -20%, respectively) into safer havens. Overall foreign investment in Africa has been flat or slightly declining in the past 10–15 years. At the same time, domestic private credit in Africa is growing more slowly than in other emerging markets, so ebbing foreign investment has not been materially replaced by domestic capital.

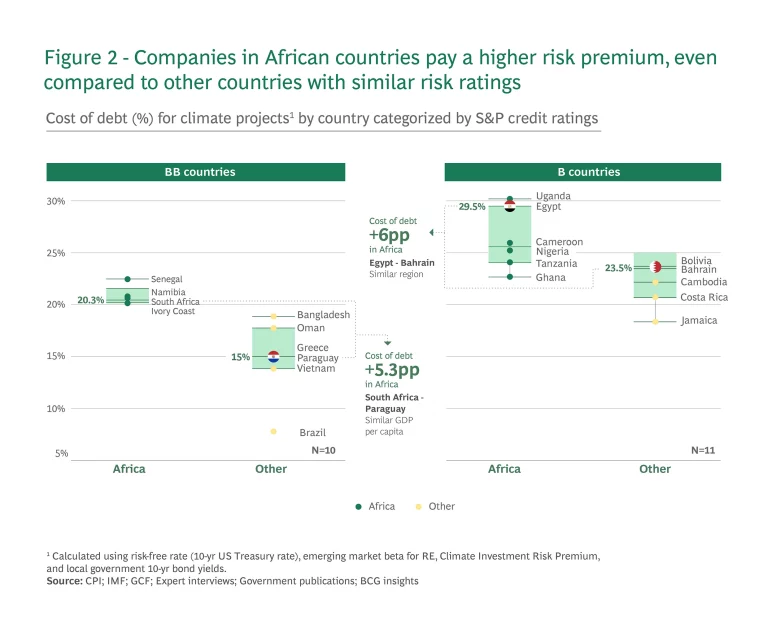

The cost of capital in African countries—even countries with similar risk ratings—is far higher (5%+) than in other regions. For example, the cost of debt for climate projects in South Africa is 20% compared with Paraguay’s 15%, although their sovereign ratings are the same (BB).

Notably, the average expected loss for private debt in Africa is in line with global averages, but the high cost of debt is primarily driven by higher initial default rates. Although higher default rates are counterbalanced by Africa’s post-default recovery rates, which are distinctly higher than that of peers in other regions, lenders maintain the risk premiums in order to account for high frictions in refinancing and collections.

These high costs of capital imply that, without appropriately structured and incentivized debt, uptake will remain low for green sectors.

In a survey conducted by AVCA on Limited Partners (LPs) in Africa (2021)

Solutions to Unlock Financing

Putting efforts into improving macroeconomic conditions is imperative to address a range of challenges faced by private companies in green sectors. This includes strengthening institutions, developing local talent and capabilities, and professionalizing sectors to ensure investments can secure a return on capital and crowd in additional funds from international and local investors.

If sufficient resourcing and policy are developed in these areas, appropriately structured financing instruments can be scaled to increase availability of capital and reduce costs. Private debt is particularly important for green sectors, which are more infrastructure and working capital intensive.

Currently, higher levels of capital are looking to invest in climate assets both globally and in Africa. For example, the UAE has launched Altérra, a new $30 billion catalytic climate investment fund with major allocations to emerging markets. Such funds will only be successful if investors consider two main levers to de-risk investments, particularly in green sectors: portfolio value creation (PVC) and debt.

1. The Gap in PVC Investment in Africa

Globally, PVC—providing in-depth technical and operational assistance to accelerate growth and profitability in portfolio companies—plays an important role in achieving targeted returns for equity investors. But in Africa, only about 5% of a typical PE firm’s investment team is dedicated to PVC, against the global median of 11%.

Development Finance Institutions (DFIs)—which are the main LP investors into these funds—can play a bigger role in PVC, which will lead the way for PE firms to do the same. By developing far more ambitious technical assistance facilities to support enterprise growth, DFIs in Africa will find it easier to achieve their intended impact mandates.

2. The Opportunity for Debt in De-risking Capital in Africa

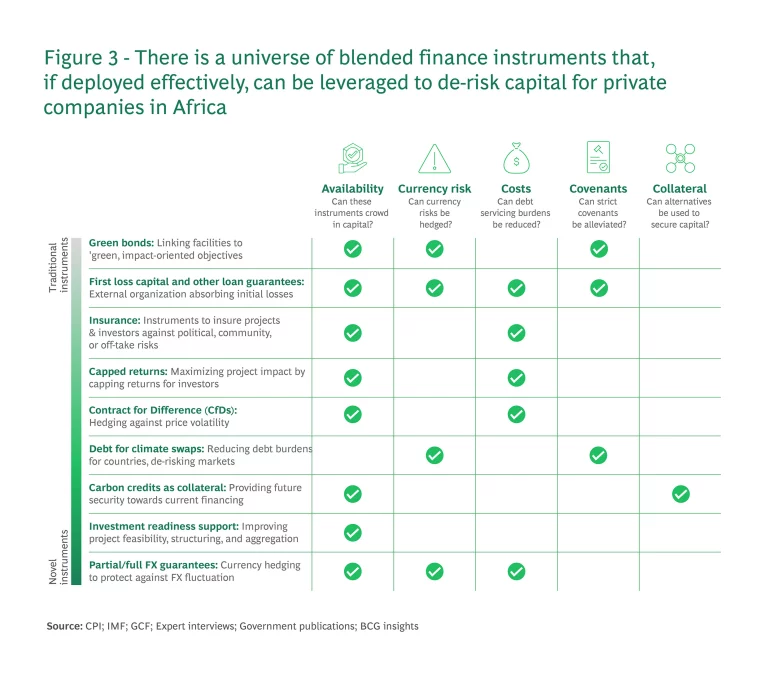

Various financial instruments, from traditional to more novel mechanisms, can be leveraged to de-risk capital. If broader macroeconomic conditions in African markets are improved, these tools can be effective in making capital more available and affordable for private companies.

Different stakeholders can and do play a critical role in scaling these mechanisms and effectively de-risking capital:

- Governments can enable favorable regulatory environments, strengthen institutions, facilitate the issuance of green bonds, and offer sovereign guarantees (if their own credit rating is sound).

- DFIs can lead on blended finance instruments, providing first-loss capital and loan guarantees to absorb initial losses and execute Contracts for Difference (CfDs) and capped return investments that can mobilize more private investment.

- Multilaterals can assist by scaling loan guarantee mechanisms, insurance products, and green bonds to improve availability of capital while de-risking markets to crowd in capital.

- Philanthropic investors can support and facilitate the use of instruments such as investment readiness support, capped return investments, or debt for climate swaps.

Effective scaling, structuring, and utilization of these instruments will bolster much-needed climate finance and support the vital growth of green sectors in Africa.