Banks are at an inflection point when it comes to financing and investing in nature. Expanded reporting requirements are being rolled out, particularly in Europe, that will require many banks and other organizations to disclose the nature-related risks and opportunities for their business. However, financial institutions should not view the push to address the crisis in the natural world as a compliance exercise. Just as banks have played a critical role in financing the energy transition in recent years—and generated robust returns in the process—they have a compelling nature-related business opportunity.

That opportunity stems from the need to mobilize large sums of private capital for nature. The vast majority of nature-related investments currently come from the public sector. But ambitions to reverse the dangerous decline in natural systems will require an estimated $1.2 trillion a year in private capital, according to BCG’s analysis. Our analysis also finds that for an individual bank that has carved out a lead in the market, financing and investing in actions to advance nature can generate up to $250 million in incremental revenue.

To be sure, there are real barriers limiting nature financing. Some nature-related projects come with long timelines and uncertainty. In addition, there is no established mechanism currently for accounting for the costs or benefits to nature from economic activities. So, the negative impacts on nature from the operations and activities of companies or governments are not routinely factored into pricing, investing, and other financing decisions. As a result, those projects may need catalytic capital to make them attractive for banks and traditional investors. At the same time, government policy and regulation in many parts of the world do not fully incentivize investments in nature-based solutions.

Despite the challenges, there are attractive natured-related opportunities for banks, and leaders (including the heads of commercial, corporate, and investment banking) should mobilize their organization to capture an early advantage. Leaders can begin by gaining insight into the nature-related risks within their portfolio and by working with clients that are highly motivated to address their impact on nature. In addition, banks can work collaboratively with stakeholders in the private sector, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and governments to eliminate some of the barriers holding back private investments.

The Business Case for Banks

A number of forces—including climate change, land use changes, and pollution—are exacting a major toll on the natural world. As a result, society has already crossed six of the nine planetary boundaries that define the limits of the Earth’s capacity to support human existence. If society continues to exceed the boundaries, it will become more difficult for the planet as we know it and humanity to survive.

The consequences of the crisis in the natural world are far-reaching for business, including financial institutions. More than half of the world’s total GDP—roughly $44 trillion—is moderately or highly dependent on nature, according to the World Economic Forum (WEF). Such calculations, of course, do not capture the full value of the natural world, particularly for Indigenous peoples and local communities relying on it for their livelihoods.

Certainly, banks are taking actions that benefit nature. After all, climate and nature are intricately connected, and banks’ efforts to achieve net zero can have benefits for nature. However, in some cases, the actions to reduce emissions, such as large-scale renewable energy projects that require a significant amount of land, can have a negative impact on nature. And the pressure on natural ecosystems includes factors well beyond climate change.

If the crisis in the natural world is not yet high on most banks’ agendas, that will change for two primary reasons. First, regulatory and reporting requirements related to nature are expanding for organizations, including banks. (See the sidebar “Nature Follows the Climate Pathway.”)

Nature Follows the Climate Pathway

A pivotal moment came in 2022 at the 15th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (COP 15). Nearly 200 nations signed an agreement aimed at protecting biodiversity that included a target to protect 30% of the world’s lands, inland waters, coastal areas, and oceans by 2030. More recently, the 28th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 28) reinforced the momentum to address the crisis in the natural world. Actions included a recommitment to halt or reverse deforestation by 2030, new funding for nature-based solutions and water projects, and the expansion of a country-led initiative to protect and restore freshwater ecosystems.

Meanwhile, initiatives to encourage or require expanded reporting on nature are growing in number. For example:

- The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures has developed recommendations for how companies, including financial institutions, should understand, assess, and report on nature-related dependencies, impacts, risks, and opportunities. More than 300 companies have committed to making disclosures in line with the recommendations this year or next.

- The European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive came into effect earlier this year, adopting standards that require companies operating in the market to provide detailed reporting on environmental, social, and governance topics. All told, four of the ten topics covered by the standards relate to nature: pollution, water and marine resources, resource use and the circular economy, and biodiversity and ecosystems.

- The Science Based Targets Network has released an approach to help companies set and track their progress on nature based on science-based targets.

Second, and perhaps even more critically, financing investments in nature are a major, untapped opportunity for banks . Most banks see the financing of nature-based solutions via the voluntary carbon market as the primary nature-related opportunity. But that view is too narrow.

To quantify the private sector nature-related investment that is currently needed, and the business opportunity for banks in particular, we analyzed the two primary types of investments: direct investments in nature and nature-adjacent investments. As much as possible, we aimed to include only those investments that support nature—not financing that is geared largely to addressing climate change. To that end, we excluded voluntary carbon markets from our analysis.

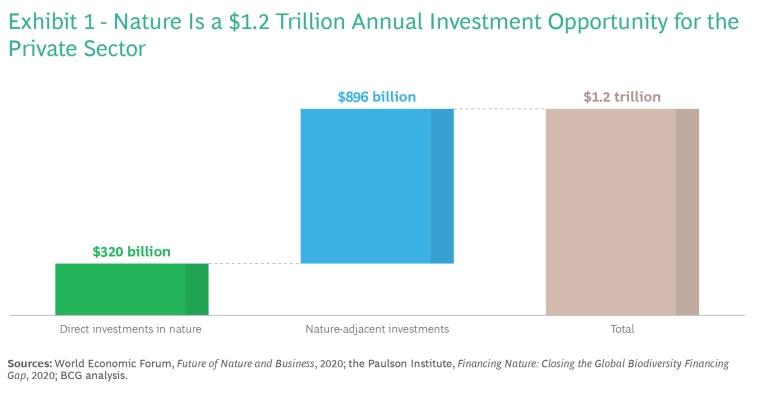

All told, we estimate that from now through 2030, an annual $1.2 trillion investment in nature is required from the private sector. (See Exhibit 1.)

Direct Investments in Nature. Direct investments in nature finance actions, or levers, to support natural ecosystems. For example:

- Agricultural land transition, either to natural ecosystems or to land that is cultivated using farming practices, such as regenerative agriculture

- Biodiversity conservation in urban environments

- Protected area expansion

- Invasive species management

- Critical coastal ecosystem restoration

To quantify the direct investment in nature that is needed, we drew largely on data from the Paulson Institute, which tracks the investment required to conserve 30% of the Earth’s land and sea by 2030, a primary target agreed to at the 15th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (COP 15). About $700 billion a year is required to meet that target, according to the Paulson Institute. Annual public-sector direct investments in nature that are currently about $165 billion will need to jump to roughly $380 billion. And annual private-sector direct investments will need to reach about $320 billion, up from just $35 billion today.

Nature-Adjacent Investments. To quantify the nature-adjacent opportunities, which help maintain, enhance, and restore natural ecosystems, we drew on data from WEF. For example:

- Water and waste infrastructure investments are needed to establish efficient water supply and sanitation facilities. They also are required to help implement systems to reduce, recycle, and responsibly dispose of waste.

- Nature-positive infrastructure needs investments to enhance its resilience against climate shock. And nature-positive transportation requires funding to adopt technologies (such as the Internet of Things, AI, and big data) to develop and optimize green long-range transportation.

- Nature-positive metals and minerals extraction requires investments to, among other things, implement processes for the recovery of resources that can be reused in operations and to share infrastructure among mining operators.

- Transparent and sustainable supply chain investments are needed for, among other things, adopting technology in supply chains, reducing food waste in the value chain, and promoting farm to fork models.

Our analysis finds that nearly $900 billion in annual nature-adjacent investments is needed from the private sector.

A Trillion-Dollar Opportunity. The $1.2 trillion in private sector capital that is required for nature investment reflects the amount needed for 14 different levers. However, just 6 of those levers account for the bulk—80%—of the total investment that is needed. (See Exhibit 2.)

As primary providers of capital, banks are in a position to provide a significant portion of the required financing and to work collaboratively with clients on their nature-positive journeys.

Notably, the list of forward-looking companies taking action to reduce the impact of their business on the natural world grows longer every day. Nespresso and LVMH, for example, have adopted frameworks and struck partnerships to track and reduce the impact of their operations on biodiversity. Biopharmaceutical company GSK has set a concrete nature strategy that focuses on avoiding and reducing negative impacts on nature across its value chain, taking action to protect and restore nature, and driving broad, collective action. BASF set a goal of processing 250,000 metric tons of recycled and waste-based raw materials annually by 2025, replacing fossil raw materials. The company also aims to double sales that come from solutions based on circular principles by 2030. Apple, meanwhile, has adopted a new strategy related to water use that includes reducing its overall freshwater demand by adopting a low-water design approach for its products, services, and sites, as well as replenishing corporate freshwater withdrawals in water-stressed areas.

A Deep Dive into the Opportunity

To assess where to focus their nature-related efforts, banks need to understand which levers and which industries offer the most compelling financing and investment opportunities.

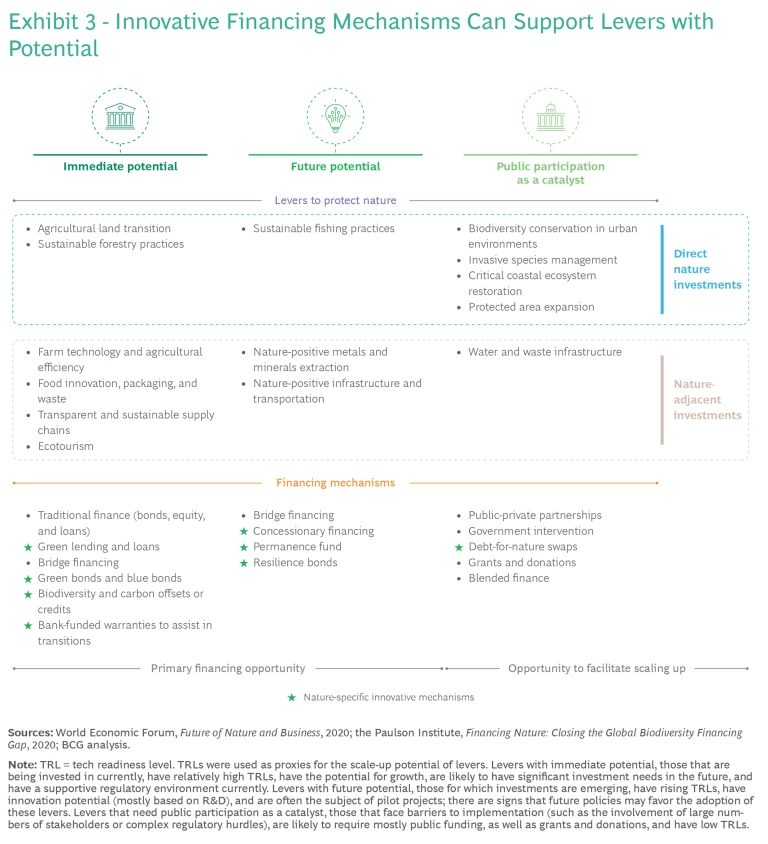

Levers for Protecting Nature. The 14 levers differ not only by the magnitude of the investment needed but also by the type of opportunity that they represent:

- Immediate Potential. Levers that have immediate potential can be deployed at scale, have growth potential, and are typically supported by existing regulations. These levers are likely to generate solid near-term returns, making them attractive for lenders and private and institutional investors.

- Future Potential. Levers that have future potential are typically based on emerging technology that is still in the development phase but represents significant improvements over existing methods. These levers are often supported by upcoming regulatory changes and can create a first-mover advantage for investors that take the lead and finance them.

- Public Participation as a Catalyst. The potential for some nascent levers depends on public participation. These levers can be complex and challenging to implement, but public sector support can mitigate implementation barriers and help unlock widespread private investments.

Banks have two primary mechanisms through which they can play a role in the deployment of these nature-positive levers: investment management (including venture capital, private equity, and asset management) and capital markets and lending. The integration of nature risks and opportunities into investment management is starting to take root. However, the most compelling business case for nature today is in the capital markets and lending business.

Banks can zero in on the best near-term opportunities in capital markets and lending by assessing both the maturity of the levers and the available financial instruments. (See Exhibit 3.)

Green and blue bonds, sustainability-linked loans, and other nature-specific innovative instruments are becoming a part of the standard financial toolkit. In addition, banks can integrate a nature lens into the traditional bond, equity, and lending segments of their business.

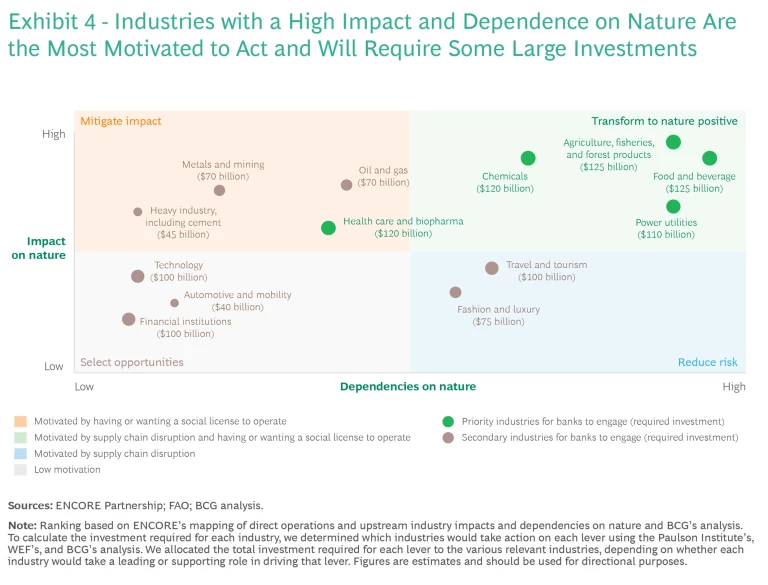

Industries with Significant Impact. A number of industries can drive progress on the levers. However, only some are motivated to act. (See Exhibit 4.) To understand which industries are likely to take the lead, we assessed which have the greatest impact and dependencies on nature using ENCORE, a tool of the ENCORE Partnership.

We then grouped the industries into four categories on the basis of their motivation to act:

- Transforming to Nature Positive. Industries that are both exposed to nature-related risks and have a high impact on nature have a significant urgency to transform.

- Mitigating Impacts. Industries that have a low dependency on nature but a high impact are motivated to mitigate that impact.

- Reducing Risks. Industries that have a relatively low impact on nature but are highly dependent on it are motivated to reduce their nature-related risks.

- Selecting Opportunities. Industries with neither a high impact nor a significant dependency on nature can nonetheless be well positioned to capture nature-related opportunities.

We also calculated the size of the investment required for each industry by considering whether an industry would be leading the progress on the various levers or supporting them.

The agriculture, fisheries, and forest products industries depend on and heavily impact nature. When combined, they have the largest investment needs—equal to those of the food and beverage industry, which is similar in its nature dependency and impact.

After analyzing the levers and industries involved, we estimate that nature can add more than $250 million to an individual bank’s top line. This figure is based on the revenue contribution from nature-related business in the capital markets and lending operations (and does not include investment management). It also assumes that the bank has an 8% to 10% share of financing for each industry, and it estimates that 80% of activity is via capital markets financing and 20% is through balance sheet lending and project finance.

Seizing the Nature Opportunity

Although the opportunity is compelling, banks face barriers in scaling nature financing. For one thing, government policy and regulation often fail to adequately incentivize investment in nature-based solutions. For another, financial institutions are confronting operational barriers, including:

- Economic Return Concerns. Nature-related projects frequently require longer financing timelines than traditional investment horizons. As a result, projects’ short-term returns are often uncertain and are therefore less attractive for banks and traditional investors.

- Risk Mismatches. A significant gap exists between the risk profiles of nature-based projects and the risk appetite of lenders and investors, often deterring investment.

- An Evolving Nature Ecosystem. The nature ecosystem continually changes as new players get involved and as regulations, definitions, and measurements emerge. This evolution contributes to a lack of clarity among some industry participants regarding their potential role in addressing nature-related issues.

- Localized Impacts and Dependencies. Actions to address the destruction of nature must be designed and executed at the individual ecosystem level. However, for nature efforts to scale, these ecosystem-level projects need to be aggregated, such as through environmental-impact bonds, green bonds, funds, and public-private partnerships.

- Low Internal Awareness and Training. There’s a lack of awareness and training among client-facing bankers regarding the needs and types of nature investment projects.

Such barriers are not insurmountable. Banks can take several steps to position themselves to seize the nature opportunity. First, they can evaluate the nature impact and dependencies within their existing portfolio. This will help them understand which clients are the most motivated to take action on nature and where the best business opportunities lie.

Second, banks can develop a deeper understanding of the nature-related commitments, pathways, and investment plans of their clients. With this insight, they can then engage directly with motivated clients on their nature challenges and opportunities—a move that will prove increasingly valuable to clients as new disclosure requirements come online.

Third, banks can elevate their organization’s capabilities by building awareness throughout the bank and providing appropriate training. Training will be particularly important for sustainability leaders, relationship managers, credit underwriting officers, risk managers, and asset managers.

At the same time, banks can work with others in the nature-financing ecosystem to address some of the barriers limiting the flow of capital. The steps include:

- Supporting Smart Policy. Smart government policy is needed to accelerate action on nature. It should include incentives for sustainable practices and subsidies for nature-based solutions, zoning laws that protect natural habitats, the establishment of protected areas, and support for large-scale reforestation or conservation projects. Although such changes are in the purview of the public sector, financial institutions and other players in the ecosystem can support and tap into supportive policies and regulations.

- Partnering on Risk Mitigation Strategies. Banks can also work with government to identify risk mitigation strategies. Among the options is the development of blended finance models, where public funds are used to attract private investments by reducing risks. Two other risk mitigation strategies are guarantees or insurance schemes for nature-based investments and debt for nature swaps, where a portion of a nation's foreign debt is forgiven in exchange for local investments in environmental conservation projects.

- Collaborating Across the Ecosystem. Banks can work with NGO’s, project developers, and other stakeholders on projects that demonstrate the economic viability of nature investments. For example, large-scale projects such as watershed restoration or sustainable fisheries management initiatives can serve as case studies for how to generate solid returns from nature investments.

A number of forward-looking banks have already carved out a lead in the nature space by taking action on many of these fronts. (See the sidebar “Learning from the Leaders.”)

Learning from the Leaders

At the same time, some banks are playing a central role in financing major nature initiatives. Rabobank has partnered with the UN Environment Programme and others to establish a fund aimed at advancing sustainable and deforestation-free agricultural practices. The effort will use a blended finance approach, leveraging money from the fund to de-risk projects, with the ultimate goal of catalyzing $1 billion in investment in agriculture transformations. And financial institutions are supporting large companies on their sustainability journeys. In 2021, Goldman Sachs partnered with Apple and Conservation International to establish the $200 million Restore Fund that invests in carbon removal via forestry projects.

Meanwhile, banks are advancing financial innovation, including the use of debt for nature swaps. CIBC FirstCarribbean was a joint lead arranger in 2022 for the $146.5 million blue bond for the government of Barbados. Under the deal, Barbados retired some existing debt and will use savings generated under the arrangement to fund marine conservation. Late last year, the Bank of America facilitated a deal under which The Nature Conservancy refinanced debt owed by the nation of Gabon, with the deal enabling Gabon to contribute $125 million toward ocean conservation.

The nature opportunity is also evident on the asset management side of the business. Although the market for nature-focused funds is still relatively nascent—nearly $60 billion in 134 biodiversity-related funds in the third quarter of 2023, according to MSCI—it is growing at a healthy clip. A number of financial institutions, including HSBC and Karner Blue Capital, have created funds focused on protecting and enhancing biodiversity.

Nature financing presents a compelling opportunity for banks whereby they can create positive environmental impact, support their clients’ transitions to a nature-positive future, and strengthen their core business. Bank leaders who move now can build an advantage in what is sure to be a significant new area for client engagement.