For companies in process industries, growth in the future may depend on resetting costs now. A confluence of factors not seen in decades has put costs front and center for these companies, threatening their ability to take advantage of both organic and inorganic growth opportunities because of expanding financial constraints.

The challenges are not confined to individual business units or parts of an organization, such as procurement or marketing and sales. Incremental cuts that attack one or two functions—the kind of moves most companies have been making for years—are no longer enough to establish a firm cost footing. Companies’ exposure to a variety of negative factors, including weakening demand, rising prices for energy and raw materials, increasing labor and financing costs, supply chain disruptions, and new trade barriers, requires a more dramatic approach. Companies should undertake an integrated review of the full business model and value proposition, tackling costs end to end, focusing on the root causes of the increases, and establishing an efficient business model for the future.

For many, this is a new scale of challenge. Companies need to attack it in an end-to-end manner.

Costs, Complexity, and Uncertainty

Process industries (including agribusiness, building materials, chemicals, forest products, pulp paper and packaging, and metals and mining) are being buffeted by a one-two punch. Costs are rising—across the board—pressuring margins. At the same time, complexity and uncertainty impede their ability to respond. Material and commodity prices, for example, have seen massive swings over the last few years and are now three times as volatile as they were at the turn of the millennium.

Companies have been whiplashed by the sudden shift from falling demand during COVID to rising inflation, interest rates, and labor costs post-pandemic. Global operations and supply chains expose process companies to geopolitical uncertainty and new trade barriers. Supplier costs are big and often unpredictable factors. Not only are labor costs ballooning, but competition for talent is increasing, retention is becoming more difficult, and many companies are experiencing “brain drain” as long-tenured baby boomers retire key skills and institutional knowledge as they leave the work force. In developed markets, companies’ asset bases are mature, highly specialized, and technologically advanced and optimized. In others, operations are less advanced and automated and therefore less efficient.

Ironically, many process companies, especially those operating in commoditized markets where tight cost control is fundamental to profitability, are victims of their own success. These companies have a long history of driving costs out and already run lean. Another round of continuous improvement or organization redesign is unlikely to result in the step-change improvements that companies need now. Furthermore, highly integrated operations and supply chains mean that cost cutting in one function, market, or region is more than likely to be felt in another—and not necessarily with positive effect.

To stay competitive (or to re-establish a competitive position) in markets that themselves have undergone fundamental change in the last few years, process companies need to rethink, and possibly reset, their business models, including their value propositions. Key questions include:

- Are they low- or high-cost producers?

- Do they have the necessary value chain and geographic coverage?

- Are they maximizing productivity and returns from their assets, or can capital be better deployed elsewhere?

- Are supply chains stable and advantaged or is redesign a priority?

- Are raw-materials supply, access to labor, and asset footprints advantages or disadvantages compared with competitors?

End-to-End Benefits

Process companies have multiple cost-resetting levers to pull. (See Exhibit 1.) These include procurement (high raw-materials and services spending), operations (extensive asset bases focused on raw-materials conversion), and supply chain (a large cost driver in materials-intensive, global value chains). R&D is another potentially powerful lever, depending on the company’s positioning and place in the value chain and the degree of development and product customization in the business model. Marketing and sales and general and administrative costs are additional functions whose size varies.

Companies can pull these levers individually, which management teams most often choose to do. In our experience, they achieve good results: on the order of 5% to 10% reductions in the addressable baseline in each area over a two-year period. (See “Pulling Individual Cost Levers.”)

Pulling Individual Cost Levers

Procurement. For companies in commodity industries, procurement can make up 70% to 80% of the total cost base, with direct spending being the largest portion. Typical savings are 5% or more in highly standardized or commoditized markets. They can reach 5% to 10% when more flexibility in contract renegotiations comes into play.

Short-term levers include supplier renegotiation and benchmarking, long-tail spending cuts, elimination of nonessential external services, and reviews of policies such as travel and entertainment. Medium- to long-term levers involve demand management (especially for services), alternative materials-sourcing options, use of less expensive materials, supplier qualification reviews, and supplier replacement.

Operations. Companies can expect savings of 5% to 10% in smaller-scale or highly automated operations with limited capex. They can expect savings of about 10% in larger, more manual operations and savings of 10% to 15% when capex initiatives (which typically involve a two- to three-year payback threshold) are included.

Some short-term levers for companies whose operations involve costly materials or high materials intensity include:

- Minimizing materials losses through better cleaning and changeover planning

- Reducing the cost of poor-quality products, effective loss analysis, and loss mitigation

- Driving maintenance efficiency (particularly in terms of prioritization and planning to reduce or eliminate critical breakdowns)

- Optimizing logistics through improved planning and utilization of equipment to ensure maximum efficiency when moving large volumes of material and products

Supply Chain. Supply chain cost levers vary substantially depending on the industry and business but, generally speaking, complex global supply chains offer greater opportunities for savings, which are typically in the range of 10% to 15%, while short and standardized supply chain savings range from 5% to 10%. The savings are smaller when companies are not considering structural elements (such as warehouse consolidation) and are larger when the full footprint is under review.

Short-term levers include increasing delivery pack sizes, running more full-truck loads, increasing direct shipments to the customer, and reviewing in- and outsourcing procedures. Long-term levers could involve warehouse consolidation or relocation and alternative delivery routes and transport methods (such as train versus truck versus barge).

Marketing and Sales. Savings from cuts in marketing and sales tend to be limited (in the 5% to 10% range) unless revised customer segmentation, new service levels, and alternative service models (such as inside sales) are included, in which case the savings can rise to 10% to 15%. Changes such as improved tailoring of the product portfolio to customer demand can also enable topline improvements. Some short-term moves are sales force effectiveness reviews and revised customer segmentation, especially pushing more customers into lower-cost service categories. Medium- to long-term levers are inside-sales setups, including customer service and alternative- channel strategies.

Research and Development. R&D cuts are generally hard to quantify as savings depend on the extent of R&D portfolio review. Without cuts to the portfolio itself, the best lever is efficiency (removing non-value-adding activities, for example) and automation, which can produce savings of 5% to 10%, though typically the savings are less. Short-term levers include reviewing the R&D portfolio and eliminating patent renewals. Medium- to long-term levers are increasing lab automation or redesigning labs and outsourcing and relocating or offshoring research services.

General and Administrative. Short-term levers, which can save 5% to 10%, include outsourcing and eliminating services or “rightsizing” functions. Medium- to long-term levers, such as offshoring and shared-service-center setups and end-to-end process streamlining and automation, can result in savings of 10% to 20% but can also result in lower service levels.

But in today’s challenging circumstances, incremental savings may not be enough. Management teams should look at costs as a potential advantage and way to reignite growth by, for example, achieving a better position on the industry cost curve or boosting asset utilization to diminish the impact of fixed costs. An end-to-end approach, which addresses the cost levers both individually and collectively from the top down, can double the savings—to 10% to 20% or more—across a broader cost base. A comprehensive approach also ensures that cuts in one area do not have unintended consequences in another and that cuts are consistent with the company’s overall business strategy and priorities.

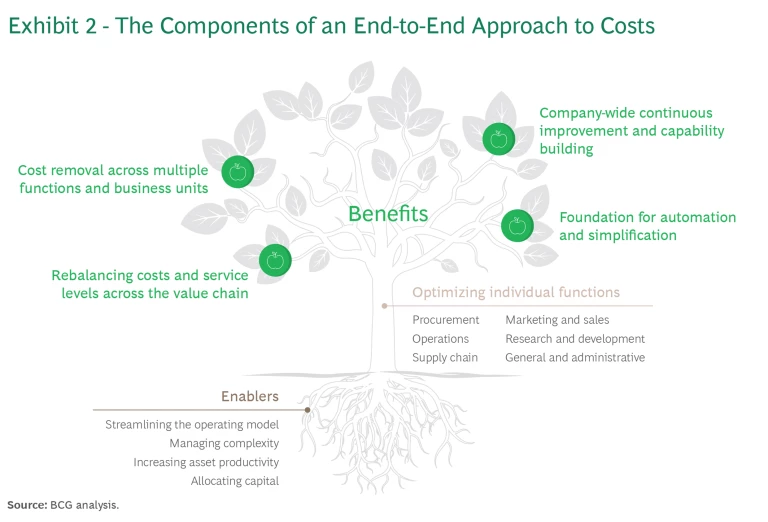

As shown in Exhibit 2, an end-to-end approach enables broad cost savings through a number of mechanisms.

Cost Removal Across Multiple Functions and Business Units. Changes in one part of the value chain can enable savings elsewhere. For example, simplifying product design or reducing technological complexity can lead to efficiencies in R&D, procurement, manufacturing and supply chain, and overhead functions. Customization at the latest possible point in the value chain can serve multiple business units or geographies with the same products or production technologies. Productivity increases are unlocked in business service functions, such as finance or IT, through simplification, standardization, and harmonization of the services rendered to other functions.

Rebalancing Costs and Service Levels Across the Value Chain. Redesigning customer segmentation and the associated service levels can result in savings from raw materials to distribution. It can also put “make” versus “buy” decisions under the spotlight. Such savings are only captured in an integrated approach when, for example, marketing and sales works with product management and supply chain functions to design, source, manufacture, and deliver a customer-specific, but not overspecified, product line.

A Foundation for Automation and Simplification. Achieving a balanced cost position among functions and business units in line with an overarching ambition provides the foundation for automating and simplifying processes, systems, and external services in order to increase scale and remove systemic complexity and costs. These benefits are most evident in cross-functional cost categories, such as IT, procurement, and R&D.

Company-Wide Continuous Improvement and Capability Building. A company-wide cost program can be used to shift the mindset of the organization towards integrating cost efficiency into daily work. A formal continuous-improvement program helps ensure that cost efficiency remains front of mind after the formal program ends, delivering additional benefits over time. Forward-looking companies build the skills and capabilities necessary to integrate the cost-cutting program throughout the organization so that they gain long-term benefits.

Four Enablers

The end-to-end approach involves four enablers across the organization.

Streamlining the Operating Model. Simple organizational structures with fewer layers and processes limit interfaces and push P&L responsibility down to the lowest possible level. New ways of working can consolidate functions, geographic areas, offices, and regions and produce significant savings though greater efficiency.

Managing Complexity. Reducing the number of products, production technologies, or product and R&D platforms eliminates complexity throughout the value chain, with direct impacts—such as improved production output or fewer resources devoted to R&D—seen in individual functions and parts of the value chain.

Increasing Asset Productivity. Improving productivity across the network (through robust operating practices, lean production systems, maintenance excellence, and better capabilities on the frontline, for example) increases throughput and dilutes fixed costs on a per unit basis. Improved productivity also provides opportunities to reduce labor costs and shrink the asset base. These measures typically take longer to show progress than other cost levers, but when executed successfully, they offer fundamental, scalable, and sustainable results.

Allocating Capital. Allocating capital to the most beneficial investments and maximizing such KPIs as return on investment and speed of delivery further enable cost reduction (and customer service) efforts. Applying a cost lens to capital allocation also helps achieve bang for the buck.

How It Works

Consider the case of an international chemicals company with $12 billion in revenues and some 9,000 employees that cut costs by more than 10% through an end-to-end program, with half coming from labor cost reductions. The company had come under strong profitability pressure because of shrinking markets, significant fixed-cost increases, and an unsuccessful portfolio expansion. Operations in North America (the company’s largest market) were declining in competitiveness because of high energy, raw-materials, and manufacturing costs.

A cross-functional team involving more than 20 workstreams identified cost-saving initiatives across all functions. A program management office ensured cross-functional alignment and adherence to the end-to-end approach. The company designed a new operating model that simplified the value chain, leading to the removal of interfaces across support functions, greater accountability for costs by function, and better management of product complexity. It aligned R&D activities with customer demand and streamlined its product portfolio, which resulted in a leaner and simpler organization.

In another instance, the iron ore mining operations of a large international metals company, with open-pit mining and processing operations and rail and port assets, experienced a substantial increase in costs during the COVID pandemic, along with a significant labor strike and commodity price risk.

The company launched a transformation to reset the foundation of its business. It used lean principles to improve operations and maintenance and designed initiatives to reduce costs company-wide, addressing suppliers, internal demand, contract leakage, and cost governance processes. It boosted equipment utilization and performance through dispatch and payload optimization, and it improved shovel performance through new operating standards at the rockface and support equipment that ensured ideal shoveling conditions. A revamped maintenance strategy that focused on identifying and addressing the root causes of equipment failure, as well as improved maintenance governance, execution, and tools, led to further operational efficiencies and a significant drop in maintenance costs. The company also leveraged its technical expertise to identify initiatives for operational cost reduction and optimization of contract spending.

In its first 18 months, the lean transformation led to a 10% increase in iron ore production on the same asset base, while the cost initiatives captured $100 million in savings out of the $200 million identified.

Programs such as these are not without their challenges, compromises, and tradeoffs. The success of a significant change effort requires highly structured planning that considers different strategic scenarios in order to understand how to balance uncertainty and risk with expected returns. Maintaining flexibility is critical to managing an uncertain future. Companies need to walk the tightrope between step-change improvements and compromises made in the interest of flexibility. Success factors include:

- A clear case for change coupled with open, honest, and frequent communication to get the organization onboard and avoid long periods of uncertainty

- Strong targets and incentives that link back to individual performance and the program’s overall goals

- An absence of sacred cows or untouchable systems, processes, or cost centers

- Consistent and recurring prioritization of resources (time and people), focusing on high-impact, high-value initiatives and critical enablers

- Rigorous execution management with a dedicated team, such as a transformation management office, to monitor, track, and facilitate timely implementation

Process companies face a new-normal business and global environment. The cost-cutting practices of the past, however successful, may not be enough to sustain competitiveness or increase it going forward. An integrated approach to costs, which looks at the problem as a whole and enables savings across the organization, is more complex and sometimes riskier, but it will yield bigger savings and more long-lasting solutions. End-to-end cost reduction should be a top priority.