This article was developed in collaboration with USAID.

Efforts to eliminate carbon emissions and advance adaptation and resilience (A&R) are accelerating worldwide. But while there is an urgent need for investment in both areas, most of the funding to date has been directed toward mitigation rather than A&R. That is beginning to change—but not nearly quickly enough.

A key part of the challenge is the lack of consensus on how to measure and track the impact of A&R investments. Unlike mitigation, for which there is a unified metric—lowered emissions levels—projects aimed at reducing the future impact of climate change from hazards such as sea-level rise or extreme heat lack agreed-upon benchmarks for success. Moreover, some A&R efforts, such as the restoration of mangroves, can also advance mitigation.

Today there is no alignment among investors, governments, donors, and other stakeholders on how to quantify the benefits of A&R investments. This is holding back much-needed private-sector investment and limiting progress on the implementation of national climate plans.

A new framework on climate A&R impact measurement is needed to:

- Enable public and private investors to identify high-impact projects and demonstrate how those projects support a country’s national adaptation plan and nationally determined contributions;

- Empower governments and donors to better mobilize private-sector capital and direct it toward the most effective solutions;

- Serve as a benchmark that climate-standard-setting bodies can use to develop a unified, globally adopted A&R measurement framework.

Our proposed framework does just that. We believe it can help guide smart A&R investments and ultimately unlock the capital required to help society adapt to a warming

The Challenge of Measuring A&R Impact

As of 2023, only one-third of lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs) had submitted their national adaptation plans (NAPs) to UNFCCC, while the remainder have included only a limited discussion of adaptation as part of their nationally determined contributions (NDCs). And although adaptation finance has increased sharply in recent years—from an average of $49 billion in 2019 and 2020 to an average of $63 billion in 2021 and 2022, according to the Climate Policy Initiative—that spending is not keeping pace with the growing need for investment. LMICs alone are estimated to need roughly $212 billion per year in A&R investment by 2030.

It is not difficult to understand why climate mitigation has gained more traction than A&R in terms of investments. Measuring the impact of specific adaptation and resilience actions is a complex exercise. There are several reasons for this: First, an A&R project’s impact will vary depending on the ultimate degree of warming—but the trajectory of climate change is uncertain. Second, because vulnerability to climate change differs by location, the impact of an A&R effort in one region will often diverge significantly from the same action in another region. Third, government policies, behavioral changes among the public, and other variables all have some influence on the impact of A&R efforts.

Certainly, there are ongoing efforts to standardize A&R taxonomies, targets, and metrics, including through the Global Goal on Adaptation framework published at COP28, the Climate Bonds Initiative, and the Adaptation and Resilience Investors Collaborative. However, our review of more than 20 NAPs and NDCs reveals that much work remains to be

For one thing, there is still significant variability in how impact is measured and tracked in existing A&R frameworks and national climate plans across Europe, Africa, Asia, and South America. Even recognized metrics—like the adoption rate of climate-smart agriculture practices, for example—are not tracked consistently, being mentioned in less than half of the NAPs and NDCs that we reviewed.

There is significant variability in how impact is measured and tracked in existing A&R frameworks and national climate plans. And even recognized metrics are not tracked consistently.

Furthermore, A&R efforts typically do not have an adequate focus on implementation. NAPs typically define objectives for systems such as agriculture and food security, health, water, infrastructure, and energy. More advanced NAPs go so far as to prioritize those objectives. However, the NAPs we have reviewed, including more advanced plans, do not provide implementation guidance that includes concrete solutions (for example, drip irrigation systems) and specific projects (for example, a 22,000-hectare drip irrigation system for sugarcane in a particular country).

A Framework for Resilience and Adaptation Investment Measurement and Evaluation

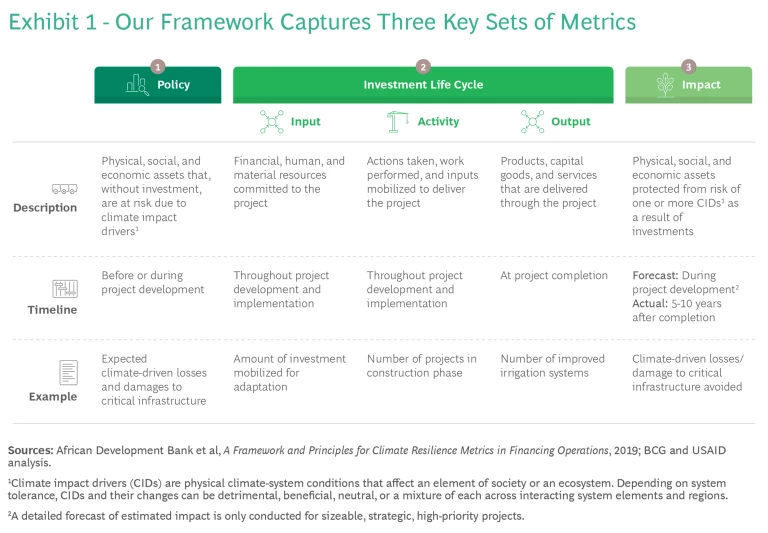

Private investors are unlikely to ramp up funding of A&R projects and solutions without a framework that guides and tracks the impact of those investments. To this end, we have developed the Framework for Resilience and Adaptation Investment Measurement and Evaluation (FRAIME). The framework is comprised of three core components:

- Policy Metrics. These measures shape government decisions on A&R by detailing the country’s vulnerabilities and the potential value at risk or cost of inaction.

- Investment Life Cycle Metrics. These reflect A&R investment progress in the short-to-medium term.

- Impact Metrics. These track the actual contributions of investments against the country’s identified A&R goals (as outlined in the country’s NAP and NDC) and its needs in the medium-to-long term.

Certainly, the framework will need the flexibility to fit the context and requirements of an individual country or investor. Nonetheless, below we detail globally tracked indicators that are relevant in many countries.

Policy Metrics

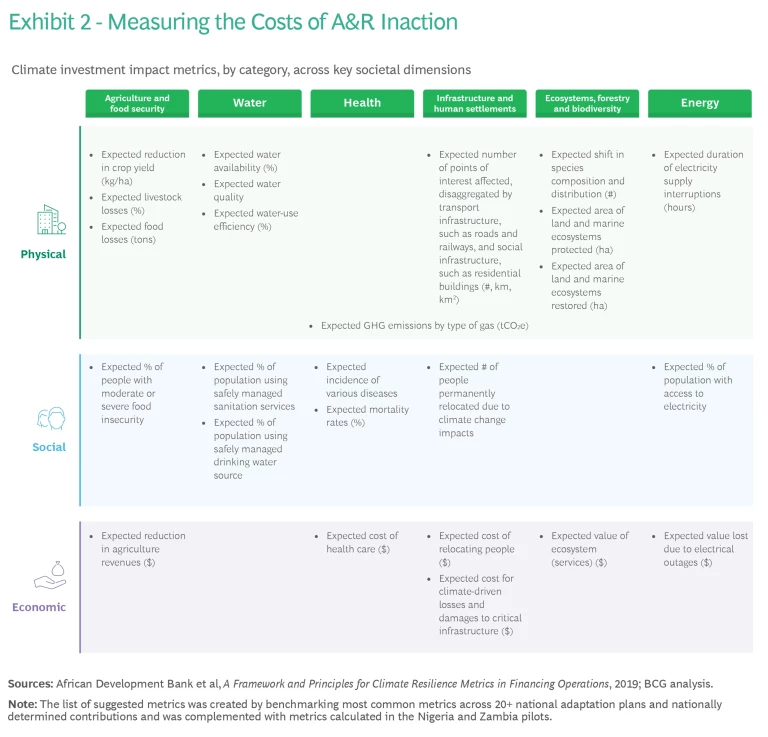

Governments should shape A&R policy based on a concrete and comprehensive analysis of the cost of inaction. Quantifying the impact of climate change on critical sectors can not only build a compelling case for government action but can also help mobilize private capital.

Governments and donors can start this analysis by taking stock of the country’s overall progress on A&R. This includes an assessment of the country’s plans and policies, including NAPs and NDCs, as well as its overall readiness, funding levels, and progress on implementation. At the same time, governments and donors should identify the country’s objectives, including those related to specific sectors or systems, and the manner in which success will be measured—for example, improving agricultural resilience against droughts and floods.

With that information as a foundation, governments and donors can then assess the country’s vulnerability to what are known as climate impact drivers (CIDs). CIDs are system conditions, such as changing rain levels and extreme weather events, that can have a positive, negative, or neutral impact on the country. Given the uncertainty about the trajectory of climate change, this assessment should be reevaluated periodically.

Based on the vulnerability assessment, governments and donors will have the foundational data to estimate the physical, social, and economic impacts of climate change in the absence of A&R investments, namely the value at risk or the cost of inaction. Depending on data availability, the most material of these impacts can be translated into financial costs and aggregated into sectoral and total value at risk—for example, the expected reduction in revenues from the agriculture sector or an increase in health care costs. (See Exhibit 2.)

AI and other data analytics are powerful tools in helping countries quantify value at risk. For example, analytics can be used to create heat maps detailing areas where a country faces significant exposure from a warming planet. Countries such as Nigeria have taken steps to quantify their exposure to climate change as part of a broad effort to boost resilience. (See the sidebar “Nigeria’s Case for A&R Action.”)

Nigeria’s Case for A&R Action

Consider the physical cost of climate change on the country’s infrastructure. (See the exhibit.) According to BCG analysis, more than $100 billion in damage to human settlements alone is possible if A&R action is not taken.

Meanwhile, roughly two-thirds of croplands are expected to be highly vulnerable to drought across 17 Northern states—making agricultural resilience investments an urgent priority.

The analysis revealed that more than half of the land and population in Nigeria will be impacted by extreme climate hazards by 2050. And a full countrywide view of all sectors, including infrastructure and agriculture, finds that the cumulative value at risk in Nigeria could reach at least $300 billion between now and 2050. This analysis has provided the foundation for the country’s drive to mobilize increased A&R investment.

Investment Life Cycle Metrics

With a granular understanding of a country’s climate vulnerability and value at risk, private investors, governments, and donors can make better decisions about which projects to invest in. To prioritize projects, these stakeholders should not only factor in positive A&R impact but also potential negative ripple effects. These ripple effects can include the greenhouse gas emissions associated with a project, the impact on nature, and the repercussions for vulnerable groups. The goal is not to eliminate all negative potential impacts but rather to break out of siloed thinking to make more informed tradeoffs between investment options.

With priority, high-impact projects identified, stakeholders can segment projects into three categories to determine the appropriate investors:

- Public Impact Projects. These non-cash-flow generating projects will typically be funded by government funds, concessional capital, and other grants.

- Blended Finance Opportunities. These projects generate near-market returns, involve the protection of private investments or assets, and are best financed by a combination of commercial and concessional capital, each taking on different levels of risk.

- Commercial Opportunities. These projects, which generate market-rate returns or involve the protection of private assets, or both, are appropriate investments for commercial banks and private and corporate investors.

For sizeable, strategic projects requiring concessional capital, impact should be estimated based on forecasts and validated and refined thereafter.

As this prioritized pipeline of projects moves through project development and implementation, private investors, governments, and donors should track and report metrics in three categories:

- Input Metrics. Input metrics track progress in how investment is being mobilized; they also identify deal-flow trends. The total dollar amount of investments mobilized will be captured along with information on each project, including the focus (for example, the sector objective and solutions) and the capital structure (for example, whether it involves public, social, or private investment). Governments and donors may wish to capture additional data depending on their investment-related goals. For example, if government aims to unlock more investment from local and regional sources, they may track investor location for each project.

- Activity Metrics. Activity metrics are crucial to assess the efficiency of government and donor investment-facilitation efforts. The number and estimated required funding of projects in the pipeline should be captured, along with project-specific information including the current stage of development (the feasibility phase, close of financing phase, or implementation phase, for example). These metrics should also include an assessment of potential negative ripple effects (whether a new sea wall could have negative impacts on natural ecosystems, for example) and the share of project leadership from underrepresented groups, including women, indigenous peoples, and youths.

- Output Metrics. Output metrics quantify the project’s immediate results and will vary based on the specifics of the project. These metrics help stakeholders evaluate a project’s cost efficiency compared to similar projects and track progress against any output targets identified in national or subnational climate plans. For example, a project that uses high efficiency dryers to reduce cereals lost to mold damage may have outputs based on the number of tons of cereals processed. Of course, private investors have their own existing investment life cycle metrics; the metrics outlined above are meant to complement and not replace those existing measurement approaches.

Impact Metrics

Measuring impact is critical to ensure that investments made are delivering the intended results and to inform cost-benefit comparisons among projects. As noted above, investors will likely need to estimate the expected impact of a project before they deploy capital to secure concessional financing and other project support. After investments are made, private investors, governments, and donors will need to verify whether change really happened on the ground in order to justify the support they provided. And investors should revise estimated impacts to reflect the actual impact delivered. This will inform future investments.

To determine impact, private investors, donors, and governments must develop a logical model that translates outputs to impacts. To reduce duplicate efforts and identify interactions, these stakeholders may decide to estimate impacts across multiple similar or interrelated projects rather than individually.

Assumptions within the impact model will be informed by various sources and should be updated periodically to ensure the most accurate estimate of impacts. They fall into two primary categories:

- Macro assumptions. These can include GDP, projected prices, and the path of climate change and can draw on a range of sources from available public information to custom, advanced simulation modelling.

- Solution-efficiency assumptions. Examples include how efficient a cereal dryer or an irrigation system might be; such assumptions draw on sources such as academic literature of pilots in similar countries, customer and stakeholder surveys, sensors, and remote sensing.

Consider a project for installing precision irrigation systems. Using sources such as academic research and farmer surveys, stakeholders can develop assumptions for the productivity of irrigated land. Applying those assumptions to the land where the irrigation system is proposed, one can calculate the volume expected to be produced by that irrigated land. Comparing that output to the output of a similar plot of nonirrigated land under drought conditions can yield the projected volume loss that is avoided through the project. Forecasts for the price of maize (for example) can be used to convert the loss of volume avoided into potential dollar-value saved.

The impact of climate change is evident around the world, making adaptation and resilience an urgent priority. Governments and stakeholders can adopt the framework outlined above to build a case for change and rally private-sector investment required to protect the physical, social, and economic assets that underpin global well-being. There is no time to waste in beginning the journey.