Despite intensive efforts to reduce malaria burden, the disease remains one of the top ten causes of death in low-income countries. In 2022, an estimated 249 million cases of malaria occurred globally and 608,000 people died of it.

By the middle of this century, climate change will meaningfully increase the numbers of people who become sick from malaria and who die of it, particularly in Africa, where 95% of the worldwide death toll occurs.

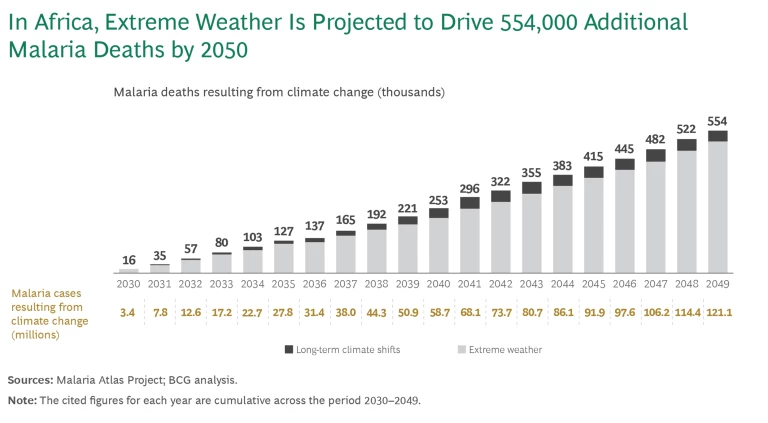

To better understand how climate change will affect the burden of malaria in Africa, Boston Consulting Group and the Malaria Atlas Project, with funding from the Gates Foundation, developed a climate model to predict changes in extreme weather events and to estimate their impact on malaria deaths through 2049. (See the exhibit.) Our modeling leverages multiple scenarios and numerical models, as well as leading insurance industry data on flood risk. The climate modeling results point toward substantially larger, more frequent, and more severe floods, along with an increase in the severity of cyclones.

Although long-term climate shifts in temperature, humidity, and rainfall will contribute to the increased burden of disease, extreme weather events such as cyclones and floods will have a much larger negative impact on disease burden owing to their disruptive effect on efforts to prevent and control malaria. These climate shocks can increase malaria infections and death in several ways, including loss of protective housing and insecticide-treated mosquito nets, and reduced access to health care , including disruptions in diagnostic testing and antimalarial treatment. Weather events also influence malaria transmission by altering mosquitos’ larval habitats.

Our quantitative impact analysis—the first and most rigorous effort conducted to date—yielded three key projections:

- From 2030 to 2049, 554,000 additional malaria deaths will occur because of climate change than would have occurred if current climate conditions had prevailed during that period. This projected increase in mortality persists even after accounting for a few places where climate change will reduce malaria transmission. We anticipate that extreme weather events, rather than long-term shifts in climate, will be responsible for 92% of the additional deaths.

- If the international community dials up its malaria control efforts using existing malaria suppression tools during that time, the number of additional malaria deaths will be smaller. But these gains are fragile, and such efforts will be up to 17% less impactful because of climate change.

- As time goes on, climate change will increase the difficulty of efforts to eradicate malaria. We project that by 2050, 75% of the population of sub-Saharan Africa—1.3 billion people—will live in areas where climate change makes eradication more difficult.

Beyond long-term climate shifts and extreme weather events, climate change will have numerous downstream impacts on malaria. For example, population displacement resulting from climate-driven migration or from conflicts exacerbated by scarce resources disrupts health care. Food insecurity, undernutrition due to lower crop yields, and worsened economic livelihoods make a person who contracts malaria more likely to get severely sick or die. Although our modeling results do not include these and other downstream impacts—such as land use changes, animal health, and health system disruptions attributable to causes other than floods and cyclones—they are likely to increase the climate-change-related malaria burden and compound the difficulty of combating the disease effectively.

In the coming years, new investments at the intersection of climate and malaria will be critical to minimizing additional malaria deaths. Largely because of gaps in funding, the world is not currently on track to meet the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals’ target of reducing the case incidence of malaria by 90% by 2030. With additional funding for vector control and malaria treatment, countries can reduce overall transmission and thereby make harder-to-anticipate surges less likely.

New investments are particularly important in five areas:

- Adapting Malaria Interventions. Pre-positioning malaria commodities in anticipation of disruptions to road access from extreme weather, for example, promotes resilience in the face of continuing climate disruptions and surges in malaria infections and death.

- Flexible Funding for Tools and Interventions. Protecting vulnerable populations after extreme weather events depends in part on solidifying the integration of malaria control measures into national adaptation plans to address climate change vulnerabilities.

- Continued Focus on Malaria Control. Modeling shows that dialing up coverage of current control efforts will save many lives, even though those efforts may be less effective because of climate change.

- Continued Focus on Malaria Prevention. Support for new tools that protect people from malaria for longer periods of time is especially critical, to improve resilience against climate shocks and to diminish the threat of reintroduction of the disease.

- Data and Decision-Making Support. Appropriate support, including early warning systems that forecast the risk of malaria outbreaks, can preempt potential disruptions to health care access following extreme weather events.

By prioritizing adaptable and resilient malaria interventions at the country level and innovative funding opportunities at the global planning level, the international community can unlock further gains in the fight against malaria and avert the worst impacts of climate change.