As a growing number of general and limited partners are focused on sustainability , several questions naturally arise: How do limited partners (LPs) assess the sustainability goals and performance of general partners (GPs)? Which climate investment strategies do LPs find most compelling? How are GPs organizing to drive sustainability in their portfolios? And what effect have their practices had on improving sustainability outcomes?

To shed light on these questions, in April 2024 we surveyed 231 members of the ESG Data Convergence Initiative (EDCI)—170 GPs and 61 LPs. Respondents were split more or less evenly across size segments and geographies, with 51% based in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa; 41% in the Americas; and 8% in the Asia-Pacific region.

See the full report appendix for additional details on the composition of the EDCI benchmark and member survey, as well as submission rates across EDCI metrics.

The survey results reveal several key insights regarding LP beliefs, what they are looking for from their investments, how they are utilizing sustainability data, and how they are directing their capital. For GPs, the survey reveals insights about how private equity funds are engaging on sustainability, including which topics they prioritize, how they approach target setting, and how they organize to deliver outcomes.

This article explores the findings from the survey, highlights emerging best practices that we believe can be adopted more widely across the industry, and concludes with recommendations for how GPs and LPs can accelerate progress in these areas.

LP Views—From Disclosure and Reporting to Engaging with GPs on Sustainability to Investing in Climate Solutions

The message from LPs is clear: Sustainability matters. Of the LPs we surveyed, 85% said they expect to increase their prioritization of sustainability-related topics over the next three years. And almost 70% agreed that “[portfolio] companies that thoughtfully consider and manage sustainability considerations warrant a valuation premium to peers that do not.” This aligns with the findings of a survey that BCG and the Sustainable Markets Initiative’s Private Equity Taskforce (PESMIT) conducted, showing that 70% of private company leaders said they expect to be paid a premium upon exit for companies that effectively decarbonized during their PE hold period. This held especially true for high-emitting sectors such as energy, industrials, and transportation.

Still, it is important to clarify what prioritizing sustainability actually means. LPs have long valued better reporting and disclosure, but how much are they measuring and rewarding improvements in sustainability outcomes? And given their interest in sustainability, are LPs directing capital towards specific sustainability goals such as climate change?

Data Collection

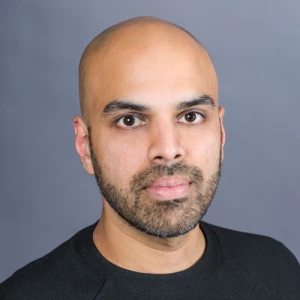

Historically, the challenge for many LPs has been the lack of reliable and consistent reporting on sustainability metrics. So it is unsurprising that 90% of LPs cite reporting and transparency among the reasons they collect sustainability data from the GPs with whom they invest. (See Exhibit 1.) However, through the EDCI, LPs now have unprecedented visibility into the sustainability performance of the portfolio companies owned by many of the GPs in which they invest, along with insights into how these performance outcomes compare to their peers.

Constructive Engagement

It is also very encouraging that a high proportion of LPs cite the desire to engage constructively with GPs on their sustainability priorities as a reason for collecting data. Gaining insights from sustainability data is a natural evolution for LPs, particularly given their conviction that improving on these metrics can increase the value of their investments.

In fact, we have heard from leading LPs that they are using these insights to have constructive conversations with GPs about the strengths and challenges within their portfolios, and to provide guidance to GPs on improving sustainability outcomes over time.

Willingness to Improve

It is notable that few LPs say they use the sustainability data they collect today from GPs to directly inform their investment allocation decisions. This is likely because most LPs do not yet have the full track record of sustainability data needed to make informed decisions, but this is expected to evolve in the coming years.

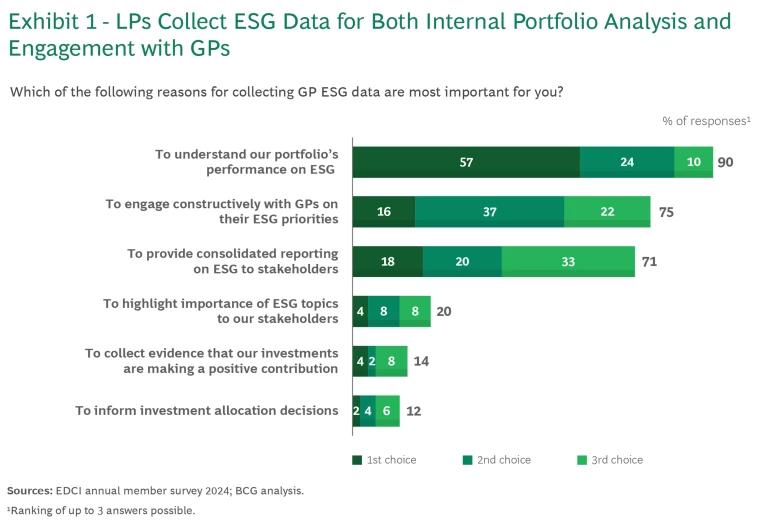

Despite this, LPs are clearly willing to act on sustainability considerations. An overwhelming 98% of LPs say they would walk away from an investment if the manager was not adequately committed to sustainability. The primary reason cited was the risk of negative publicity, which highlights the level of concern LPs have about how their investment activities may be perceived—but also shows that they understand just how important sustainability issues have become. (See Exhibit 2.)

LPs have also adopted an “it’s not about where you start, but where you finish” approach to analyzing sustainability risk. The survey shows that LPs are less likely to allocate to GPs lacking the intention to improve on poor sustainability management and performance than to those whose current sustainability performance is poor but who acknowledge the importance of addressing it. Many LPs are willing to allocate to GPs if they can demonstrate a credible plan for improving on sustainability outcomes of their portfolio companies over the duration of the hold period.

That’s the strategy used by PGGM Investments, a pension fund service provider based in the Netherlands with approximately $270 billion in assets under management on behalf of pension fund PFZW. PGGM carries out what it calls a “GP ESG Assessment” during due diligence of each potential investment, designed to “assess a GP’s ability to effectively manage ESG risks and opportunities,” says Karin Bouwmeester, sustainability and ESG expert at PGGM’s private equity team. The firm conducts the assessment every year during the ownership period. While good scores on the evaluation matter, and low scores can be a reason to decline to invest, Bouwmeester notes that PGGM in certain cases is also “willing to invest with GPs with lower scores if they are committed to improving over time.”

Directing Capital to Climate

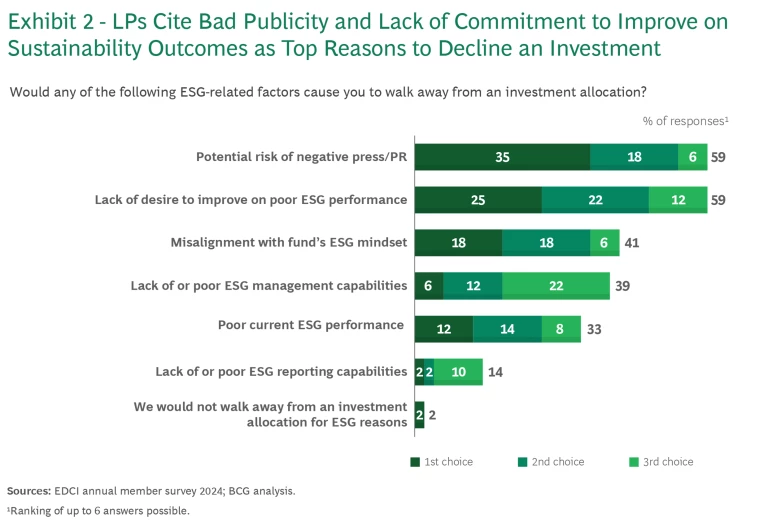

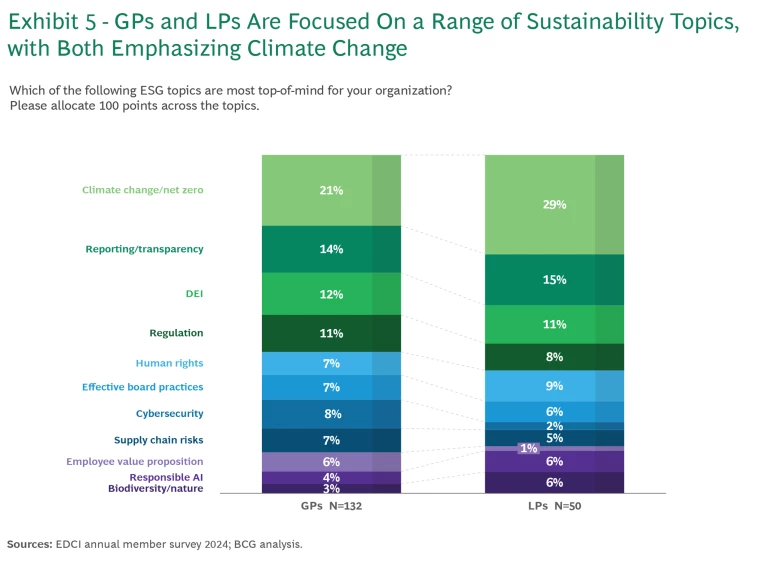

LPs currently vary on the sustainability issues that matter to them most. Unsurprisingly, they attributed the greatest weight to the climate change/net zero topic. (See Exhibit 3.) The second most important topic was reporting and transparency, a concern that does not bear directly on improving sustainability but rather on the ability for LPs to track their investments’ commitment to and progress on sustainability issues. Other direct sustainability issues, such as diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and board practices, while still important, were less top-of-mind.

Given their belief in the importance of climate change, it’s not surprising that 40% of LPs have capital allocated specifically to climate investing. When asked to specify which types of investment theses they prefer to pursue, responses among LPs were relatively evenly divided between low-emitting companies, companies working on climate solutions, and heavy emitters that are trying to decarbonize.

Although these capital allocation strategies are still in the early stages of development, we advocate for LPs to direct their investment dollars not just toward low-emitting sectors but also to the more challenging and increasingly valuable task of investing in GPs willing to drive the grey-to-green transition—a critical path to global decarbonization . Given LPs’ belief in a potential valuation premium for businesses that effectively manage sustainability, there is significant value to be gained by purchasing companies that have yet to set out on their sustainability journeys and transforming them into green leaders that can benefit from a valuation premium. Equally, the sustainability transition will require many new, innovative business models focused on effectively scaling new technologies.

PGGM takes this approach, aiming to have 30% of its assets under management contribute to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, half of which should contribute to climate-related SDGs. Climate is a key area for them, and the firm has a mandate to invest in private companies and infrastructure projects focused on avoiding so-called Scope 4 emissions that occur predominantly outside of a company’s own greenhouse gas (GHG) inventory as the result of consumers using the company’s products and services. LPs like PGGM have chosen this approach “because you can apply it quite broadly across asset classes, investment strategies, and climate topics,” says PGGM’s Bouwmeester.

To provide a tangible example, the pension fund PFZW invests in early-stage climate solution companies such as SCW Systems (SCW), an energy services company with a mission to contribute to the cooling of the planet. SCW has developed two independent technologies that assist in delivering on its mission. The first consists of converting organic waste streams, such as sewage sludge and plastics, into green gas and green hydrogen, both of which have a major role to play in the energy transition. The second involves a technology for capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere using less energy for the direct air capture process than previously thought likely.

GPs See the Link Between Sustainability and Value Creation

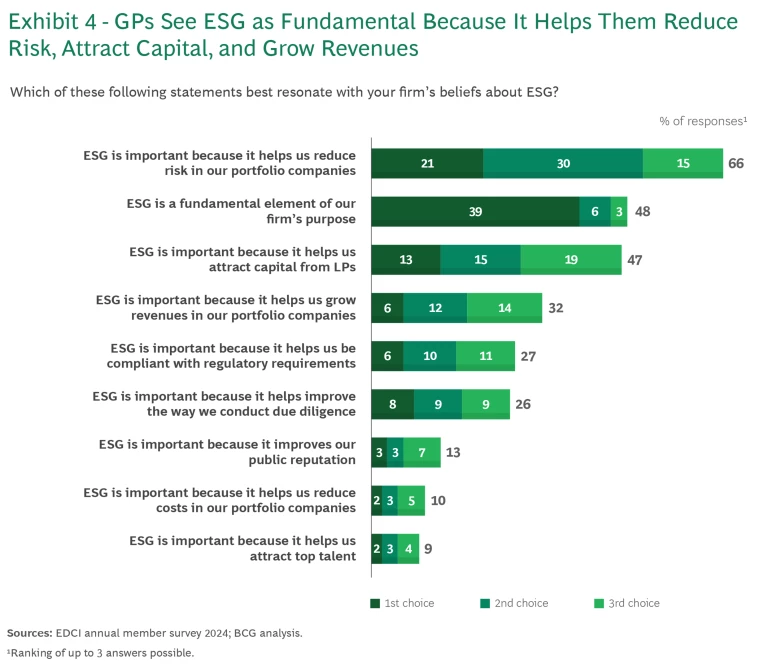

Many of the GPs we surveyed are committed to sustainability, with half of respondents saying it is fundamental to their firm’s purpose. (See Exhibit 4.) An even larger proportion—two-thirds—said sustainability is important because it helps reduce risk in their portfolio companies. Helping attract capital from LPs and boosting their portfolio companies’ revenues were cited significantly more frequently than historically important drivers of sustainability activities such as regulation or compliance, further supporting the belief that sustainability efforts are important for overall value creation and capital formation.

As with LPs, climate change, reporting, and DEI were the sustainability issues to which GPs attributed the greatest weight. (See Exhibit 5.) The high importance of reporting and transparency for both GPs and LPs is not surprising, as many investors are preparing to respond to requests for a variety of new sustainability reporting standards, such as those of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) or the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). However, GPs also place significant emphasis on a broader range of topics, including cybersecurity, supply chain risks, and the employee value proposition—all important social and governance issues that are likely more tangible for GPs engaged in the day-to-day management of their portfolio companies.

Committing to Sustainability

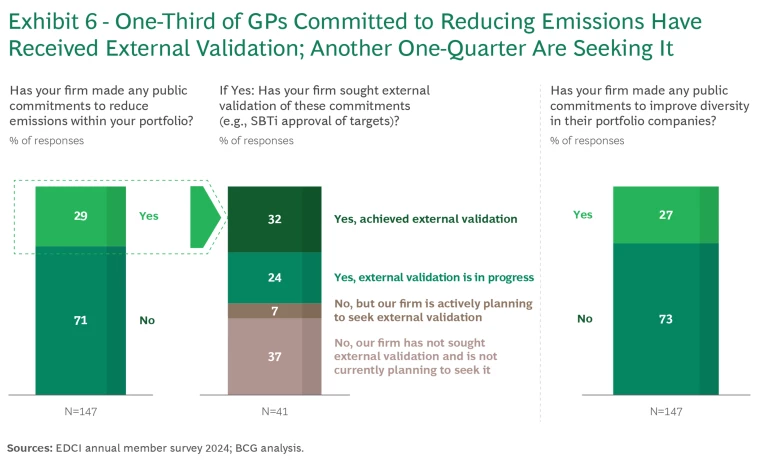

While many GPs have stated their commitment to sustainability more broadly, fewer than 30% of those surveyed have committed publicly either to reducing emissions or to increasing diversity. While there is room for improvement here, it is encouraging that the majority of those making public commitments to emissions reductions have either sought and received external validation of their emissions targets or are looking to do so. (See Exhibit 6.) Still, it is worth noting that GPs based in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa are far more likely to make such public commitments than are GPs in the Americas—45% versus just 16%—and to back them up with external validation of their emissions targets.

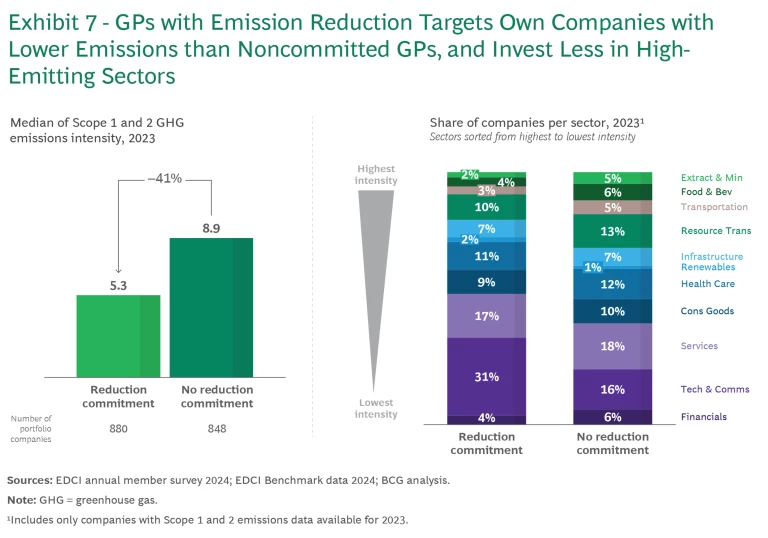

Public commitments to reducing emissions can have a significant impact. The EDCI benchmark data shows that the median Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions intensity at portfolio companies owned by GPs with public commitments was more than 40% lower than at companies without such commitments. In addition, private companies have been more successful in reducing emissions at portfolio companies than those without decarbonization strategies in place. (See “ Where are Private Equity Firms on Their Way to Net Zero? ”)

It should be noted, however, that GPs with public firm-wide commitments to emissions reductions tend to invest predominantly in relatively lower-emitting industries. For example, they are almost twice as likely to invest in the Technology and Communications sector, the second lowest emitting sector after Financials. In contrast, the average share of portfolio companies in the top-five highest emitting sectors—Extractives and Minerals Processing, Food and Beverage, Transportation, Resource Transformation, and Infrastructure—at GPs without public firm-wide commitments is 37%, compared to just 26% at those with commitments. (See Exhibit 7.) Given the urgency of addressing climate change, it’s critical that more GPs with higher exposure to heavy-emitting assets also establish equivalent emissions targets and that those with public commitments step up and lean into the challenge of transforming heavy emitters.

Many GPs have, however, made commitments to lower emissions at specific companies within their portfolios. After all, public commitments don’t necessarily need to be applied equally across a diverse portfolio. For example, some GPs are making forward-looking commitments to put in place validated decarbonization plans at portfolio companies within a set time period of ownership.

Whether done at the aggregate level or at the level of individual portfolio companies, we hope to see greater use of public commitments in the future. The EDCI can be a helpful tool to support GPs in this effort, as they have sometimes shied away from setting targets in the past due to the lack of sufficient data on key sustainability metrics. For the first time, GPs have a data-backed view on how their emissions compare to peers across their portfolios and can make more informed decisions about their decarbonization ambitions and targets.

Being Accountable for Diversity

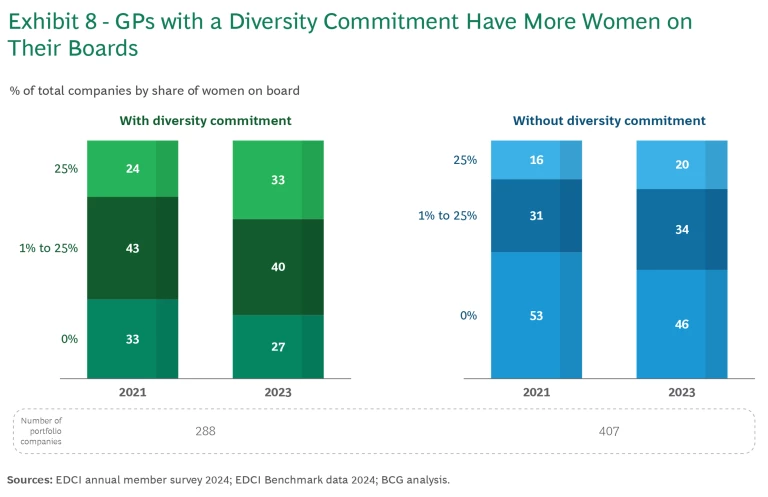

Commitment to diversity has a similar effect on actual results. At GPs with a commitment to improving diversity (which most frequently targets improvements at the board level), 65% of their portfolio companies had at least one woman on their boards, compared to 56% at GPs without such commitments. These results were consistent regardless of the GP’s sector composition or headquarters location.

Further evidence of the impact of public diversity commitments can be seen in how the share of women on boards has improved over time. For example, consider portfolio companies with over 25% women on their boards. At GPs with diversity commitments, the proportion of these companies increased from 24% in 2021 to 33% in 2023. The number of these companies at GPs without diversity commitments increased only half as much—from 16% to 20%. (See Exhibit 8.)

Setting targets can play a valuable role in the journey toward improved sustainability and diversity, especially within a collaborative framework that can help provide a structured approach to target setting and avoid many of the challenges and risks of doing it in isolation. Targets also provide a useful communication tool to engage with stakeholders and use as an accountability mechanism.

Teamwork

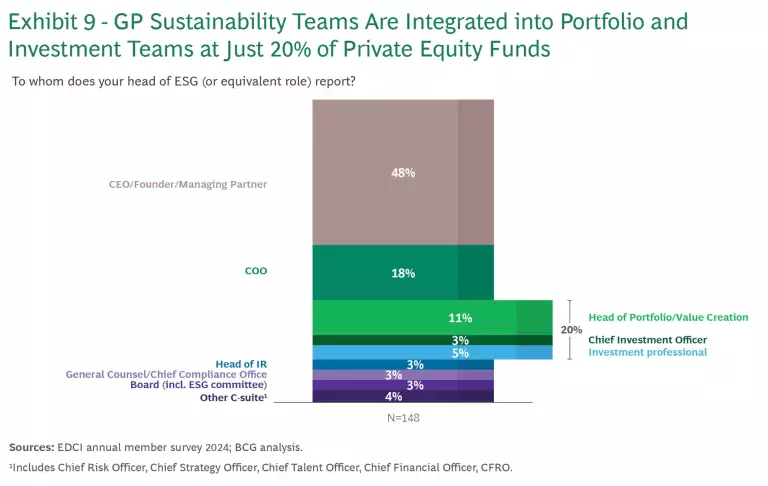

Within private equity , there is no one-size-fits-all approach to how sustainability teams are, or should be, structured. Three-quarters of the GPs we surveyed devote fewer than three full-time staff members to sustainability, a figure largely dependent on the size of the fund. At nearly half of them, the head of the sustainability team reports directly to the CEO, while just 20% of sustainability teams are integrated directly into portfolio and investment teams, reporting to either the chief investment officer, the head of portfolio and value creation, or other investment professionals. (See Exhibit 9.)

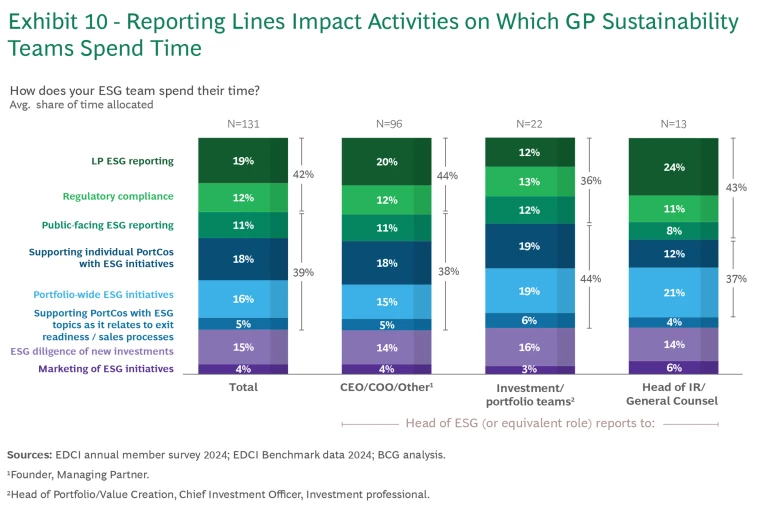

These differing reporting lines appear to have a considerable impact on how sustainability teams spend their time. Sustainability teams whose heads report directly to investment professionals spend 36% of their time on sustainability reporting and regulatory compliance, compared to 44% when they report to the CEO. And these teams spend 44% of their time directly supporting portfolio companies with sustainability issues, compared to 38% when they report elsewhere. (See Exhibit 10.)

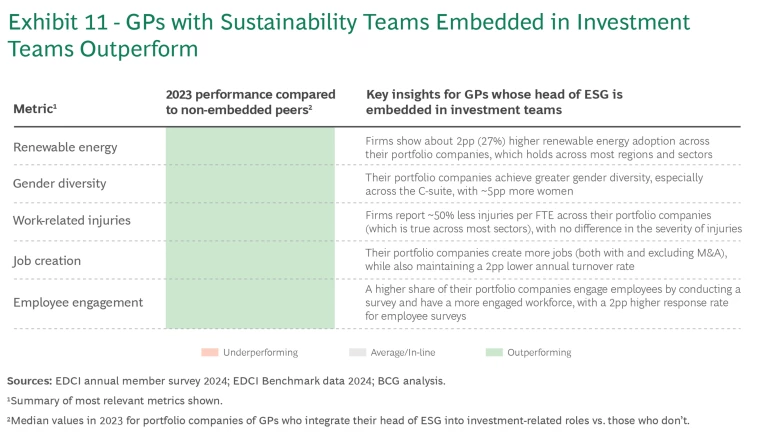

Because GPs with sustainability teams embedded into investment teams spend more time engaging directly with portfolio companies, it’s not surprising that portfolio companies at these GPs systematically deliver stronger outcomes across the EDCI metrics. For example, they reported 2 percentage point higher median rates of renewable energy usage and 50% less work-related injuries, on average, in 2023. (See Exhibit 11.) This in turn ultimately leads to commercial value creation in the form of reduced energy costs, reduced employee costs, and a more diverse leadership group pushing company agendas forward.

In contrast, GPs whose sustainability teams spend the majority of time focused on reporting see systematically lagging outcomes at their portfolio companies across most metrics, compared to those that focus on supporting portfolio companies with sustainability initiatives and due diligence. For example, they have a 5 percentage point lower median renewable energy adoption rate and a lower median share of women in their C-suites.

Action Steps for GPs and LPs

With an increased emphasis on sustainability, many LPs are rapidly evolving their practices to respond to stakeholders and directing capital effectively to those GPs best placed to deliver on sustainability and social impact . The result: they are creating value for their shareholders and stakeholders alike.

Yet the data also shows that both GPs and LPs are still on a journey to achieve their sustainability goals, and that there are significant gaps and areas where best practices are yet to be adopted at scale.

Based on the data, we recommend that GPs take the following steps to improve their sustainability activities and results:

- Rethink internal operating models and empower sustainability leaders to accelerate action by embedding sustainability teams within broader portfolio and investment capabilities. Incentivize sustainability leaders to focus on value creation through clear performance metrics, so that sustainability becomes core to the ongoing evaluation and management of every portfolio company.

- Consider making thoughtful public sustainability targets—tailored, potentially, to individual assets—for key issues such as emissions and diversity, and use them as a communication and accountability tool to support progress on outcomes.

- Share with LPs how you are investing in support of the climate transition, and don’t shy away from talking about how your portfolio might initially include investments in unloved low-performing assets if you’re focused on improving these assets over time to capture future expected valuation premiums.

As for LPs, we recommend that they accelerate their efforts to make data-driven sustainability improvements:

- Use sustainability data not only as a reporting tool to drive transparency but also to inform investment decisions and engage constructively with GPs on how to improve sustainability.

- Given LPs’ belief that sustainability improvements drive value, we hope to see more of their capital allocated to climate solutions and grey-to-green transitions that drive real-world outcomes.