The value of trust in business cannot be overstated. Companies with high levels of trust tend to demonstrate materially higher levels of total shareholder return—as BCG’s Trust Index , which measures ongoing stakeholder confidence in businesses, has found.

Yet it is harder than ever for companies to sustain trust. In recent years, many businesses have seen their stakeholders—customers, employees, investors, supply chain members, regulators, and neighbors—lose confidence in them. Our analysis reveals that almost 30% of large companies have experienced a major crisis or scandal in which peoples’ trust in them abruptly dropped. In nearly all these cases, recovery has been slow and difficult.

A breach of trust can be corrosive to a company’s revenues, its culture, and its future success. Many businesses never regain their former standing unless corrective and sustained actions are taken.

How, then, can business leaders avoid the deterioration of trust in their companies? And if trust does decline, is there a systematic path for actively regaining or repairing it?

Easy to Lose, Hard to Regain

In our previous report, we introduced the Trust Index, which applied natural language processing and AI to analyze and quantify stakeholder perceptions of a company’s reputation. Our new study looks at how 177 of the world’s largest publicly traded companies dealt with the ebbs and flows of trust in their businesses over a three-year period from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the third quarter of 2022.

During that time, about half the companies experienced extreme shifts in trustworthiness: dramatic losses or gains in the way stakeholders judged their competence, fairness, resilience, and transparency. We gathered this data from mentions and impressions (M&I) of the companies in news reports and social media. The resulting analysis revealed the patterns of organizational strategy and behavior that emerge as companies deal with changing levels of trust in their businesses. (See “Methodology.”)

Methodology

- Competence. How a company consistently acts to deliver value and thus fulfill its promises to stakeholders.

- Fairness. How equitable and empathetic a company is perceived to be by its stakeholders.

- Transparency. How open and unambiguous a company’s decision making and actions are.

- Resilience. How effectively a company avoids or recovers from challenges and crises.

Our methodology included extensive data cleaning to enhance reliability—for example, eliminating minor errors such as the word “gap” being mistaken for the retail chain The Gap. For categorization, we developed an expanded list of more than 2,000 trust-oriented keywords. We used weighted averages to include data from prior quarters with an element of historical discounting to account for the nature of public memory. Keywords were categorized across the four dimensions of competence, fairness, transparency, and resilience.

From these assessments, we derived a trust score for each company on a normalized scale ranging from -1.0 to +1.0. The trust score measures stakeholders’ level of trust in a company based on the ratio of positive to negative trust-related mentions and corresponding potential impressions they received in news and social media. A trust score below 0 indicates that negative trust-related discussion about a company exceeds positive discussion, whereas a score above 0 indicates the opposite. We calculated scores for trust on a quarterly basis, with a focus on how different events affect the movement, or change, of trust between two sequential quarters.

A trustworthy business is one that delivers on its promises to multiple stakeholders. For example, a company might be deemed trustworthy if it can fulfill its commitment to shareholders to meet its earnings guidance; if it can deliver products that meet or surpass its value proposition; or if it can honor a pledge to reduce its carbon footprint. Trustworthiness can be further broken down into four dimensions: competence, fairness, transparency, and resilience. The more consistently a company displays these four attributes, the more trust it enjoys from its stakeholders.

Seven key insights emerged from our study:

- Trust breaches represent a clear and present danger, even for businesses that seem immune to them. Nearly 30% of the companies in our sample experienced a large-scale decline in trust over the course of the three years studied. This was often accompanied by severe financial and reputational costs. Trust is easy to lose, and most companies are unprepared for the challenges that follow.

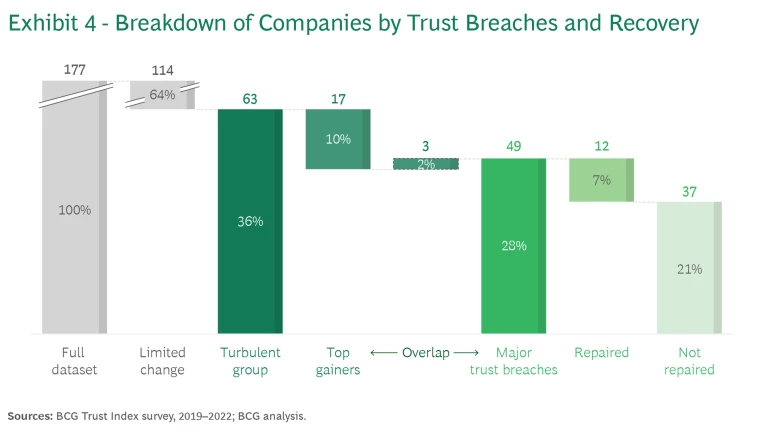

- Once lost, trust is hard to regain. Recovery takes much longer than some company leaders may expect. Only 2% of the companies BCG studied experienced a rebounding trust-creating event in the quarter after a trust breach. Just 12 companies recovered from a major trust decline and sustained that recovery through the end of the three-year period.

- Breaches of trust are usually self-inflicted. Most losses of trust have internal causes: they stem from misjudgment, organizational issues, or misaligned processes within the company. This underscores the importance—and feasibility—of actively managing a company’s trust position. Breaches of trust are often too large and severe to delegate to a functional risk or PR department alone.

- Trust crises provoke a shift in the type of scrutiny that stakeholders give companies. After a scandal or breach of promise, stakeholders are likely to look at the company’s actions with a more suspicious, even skeptical eye. “Getting out of the hole”—putting things right, rebuilding the company’s reputation, and demonstrating its competence and resilience—should become a top priority for senior management, because that is where stakeholders are focusing their attention.

- Trust repair requires both resilience and competence. To address the crisis forcefully, it’s not enough to be resilient. Competence—the ability to consistently fulfill promises to key stakeholders in every aspect of the business, irrespective of the crisis—is also required for trust recovery. By simultaneously demonstrating both qualities together, companies can achieve up to ten times the level of trust recovery than the average.

- Every trust recovery effort needs a different response, depending on the drivers of trust destruction and the company’s capabilities. The path forward must be designed to fit the crisis; in some instances, direct corrective action has impact, while indirect positive action can stem the tide in other cases.

- Systematic vigilance is key. Even if a company is well regarded or has rebuilt its trust levels, that doesn’t mean it will automatically sustain high levels of trust in the future. High trust levels can foster complacency that can lead to another trust-destroying crisis. The best protection is to habitually maintain high levels of trust by devoting ongoing attention to resilience and competence. Regular corporate self-monitoring and self-regulating practices can help provide a “stock” of trust, a backlog which can help cushion a company against further depletion.

In this article, we use illustrative case studies and quantitative insights from the most recent trust study to show how companies can develop the capacity and capability to manage trust. With the right approach, companies can recover from just about any crisis of trust. They can also prevent future crises from occurring. This happens through a gradual, multipronged process that builds and showcases the

company’s resilience

and competence.

Events That Destroy Trust

Trust changes in nonlinear ways. The trust scores of a company might shift less than a tenth of a percent from one quarter to the next—and might stay in that same range for years. But then comes a major trust-destroying event, which can diminish trust levels by more than 25% in a single month. (See the sidebar “The Range of Trust Crises.”)

The Range of Trust Crises

But even more difficult to overcome are trust-destroying events related to lack of efficacy. A company might have accidentally leaked private data, released unsafe or low-quality products, or failed to meet other baseline expectations. No companies in this group recovered their old trust levels within the study’s three-year time period. Instead, they became known for their ineffectiveness. Events related to efficacy led to the largest magnitude of loss (0.54) and tended to affect companies that would otherwise have high trust levels.

The smallest trust losses (0.29), relatively speaking, came from top-management scandals. They also had the overall highest recovery rate. Half of all affected companies recovered within those three years. Typically, the reputational blow falls on the specific person(s) involved rather than the company. The company has more options for managing the situation—for instance, by distancing itself from the cause of the trust breach.

Company accidents have the second highest recovery rate, with 43% of companies achieving recovery within the observation period. Industrial goods and energy companies, more prone to high-risk situations, accounted for 86% of these occurrences. The high recovery rates may reflect the visible response that often occurs: improving safety measures, cleaning up spills and leaks, restoring ecosystems, paying reparations, and instituting additional safeguards to prevent future occurrences, to name a few examples.

Externally driven trust crises are relatively rare, and the costs can vary. Trust loss from the external political environment has a modest recovery rate: 33% of the affected companies regain their former levels. Loss of trust from public activism is particularly difficult to rebound from. In the three-year period under study, there were no full recoveries.

In sum, our findings suggest that the characterization of a trust breach affects recovery. When the cause is deemed to be outside the company or isolated to a specific individual within it, recovery is swifter than when the company itself is to blame and the cause appears to be more deeply rooted. If the cause is truly external, then the company’s leadership can play a key part in the attribution process, identifying the relevant external causes for the crisis and communicating appropriate solutions.

These trust-destroying events can hit companies in just about every region and industrial sector. Having an established history as a high-trust company doesn’t seem to help much, either—in fact, the median trust score of companies during the quarter before they experience a big loss (.41) is slightly higher than the overall average trust score of our data set (.39).

A global insurance company (which we’ll call ClaimCo) had built a reputation for almost 100 years as a company of high ethical standards. Its trust score stood at .72, much higher than the general average of .39. Then the news broke in 2020 that some senior leaders had been implicated in a major public scandal. This discovery had a significant effect on the company’s trust score, which fell by more than half, to .36, in just one quarter. A number of major customers switched to other insurers. The company’s prior history did not lead online commentators to treat it with deference; if anything, the criticism was all the more scathing because of the inconsistency between the breach of trust and the company’s prior reputation.

Like most of the trust breaches we studied, ClaimCo’s losses were self-inflicted. Among the 66 trust-destroying events we observed over the three-year period of the study, 80% were caused internally: in other words, by a company’s own actions.

Exhibit 1 shows the six most common drivers of trust loss and their relative prevalence. Only two of the drivers, pertaining to only 21% of cases overall, are caused by factors outside the company’s control:

- Shifts in the External Political Environment. These typically involve policies, regulations, or actions by political leaders that affect a company’s ability to fulfill its value proposition. For instance, the CEO of a state-owned company might be ousted, a product might be banned, or international trade sanctions imposed.

- Public Activism. This factor captures actions by the general population—such as protests, social media eruptions, or boycotts—that may only be tangentially motivated by the company’s activities. A Twitter post by a celebrity or group with an axe to grind might suddenly provoke a stock-price tumble, or a prominent employee might be linked to an activist group in a way that embarrasses the company.

The other four drivers have roots within the company, through its decisions, practices, collective judgment, or the actions of rogue individuals:

- Company Scandals. Negative events caused within the company itself, such as perceived shirking of social responsibility, fraud and bribery, lawsuits, violations of a company’s own policies, and unpopular business decisions.

- Efficacy. Issues with products and services that compromise the company’s ability to deliver on its value proposition. These include product malfunctions, unintended negative effects on customers, and inadvertent security threats. One common example is the practice of adding on extra fees that customers don’t expect to be charged.

- Large-Scale Accidents. Incidents that cause significant environmental damage or endanger workers’ safety. A dam collapse or a factory emissions leak can occur even at companies with long-standing safety records.

- Top Management Scandals. Wrongdoing involving individual lapses of judgment and not necessarily related to company operations. Illegitimate statements by the CEO or allegations of sexual harassment could fall into this category.

The overwhelming majority of trust-loss cases are internal and self-inflicted. No business can avoid all risks of trust-destroying events, but every company can play a more proactive role in preventing and handling them.

How Perceptions Change During a Trust Crisis

The perceptions of companies tend to be favorable, especially when things are going well and the company is generally trusted. About 60% of the 177 companies in the study increased their trust levels during the 3-year period we studied. In general, these increases were not very steep; the average company’s trust level grew only .07%.

However, that average figure represents a wide range of trust profiles. In Exhibit 2, the lines from the left (the fourth quarter of 2019) to the right (the third quarter of 2022) show pathways of trust-level changes. The thicker the line, the more companies took this path.

As you can see, most companies stayed approximately level (40.7%) or moved just one tier (37%). A small number lost trust so dramatically that they moved from the very top tier to the very bottom. These are the companies that experienced trust-destroying events.

When a company goes through a trust-destroying event, its stakeholders shift their perspective. Previously, they may have paid close attention to a company’s profitability or consistent delivery on its value propositions. Now, they shift to monitoring a company’s resilience—how the company is handling the challenges that it faces. There may be a backlash from customers, new regulations, or even criminal charges to handle. There will certainly be a need for a public communications campaign, along with other priorities and interventions related to stakeholder trust: employee wellness programs or environmental, social, and governance initiatives. Compliance with rules and regulations becomes a more prevailing point of interest.

When a company goes through a trust-destroying event, its stakeholders shift to monitoring the company’s resilience.

Such a shift happened to a prominent global tech company (TechCo) known for its media platforms where people connect and communicate. It had built up a massive customer base for its products in one major country—a country with strict rules about tech ownership and data control. These rules were known to be selectively enforced, and one year, TechCo was targeted. Though its own practices and policies hadn’t changed, it was now subject to new regulations and antitrust restrictions, forcing it to back away from some of its previously announced mergers and offerings.

Some industry observers predicted that TechCo would be forced to share its local ownership or give up its intellectual property. As the news and commentary continued, and some company leaders were publicly criticized, there was a sharp decline globally in TechCo’s trust levels. It continued to survive and retain its users, but it was no longer seen, in news or social media mentions, as being in control of its destiny.

It’s noteworthy that no company achieved the same feat in the opposite direction. No company boosted its trust levels from the lowest to the highest level. This might simply reflect the lack of attention stakeholders pay to companies in the absence of a crisis, or it might represent an opportunity for some companies to try to differentiate themselves as embracing trustworthy practices.

Rebounding from a Loss of Trust

Now consider the 17 companies that moved up at least two trust levels during the three years of our study. Most of them also improved their scores at least ten times their peer-group average. (One group, on the path from tier 3 to tier 1, didn’t quite reach that latter criterion.) These top gainers represent nearly 10% of the full data set. What can be learned from their success?

Interestingly, they don’t readily match to any particular industry, region, or market-cap pattern. There is no typical trust-gaining company profile based on externally visible characteristics. They stand out because of the actions and approaches they take to ascend from their low-trust positions. They look at their trust issues as problems to solve directly. They address lawsuits, data breaches, boycotts, and criticisms with immediate, direct action.

However, simply resolving problems isn’t enough to substantially build trust; top trust gainers also draw attention to their competence, and specifically their ability to deliver on their core business propositions and meet stakeholder demands and expectations. These competence-demonstrating actions might include delivering robust business results, producing highly acclaimed products, launching new partnerships, becoming a magnet for talent, or delivering superior shareholder value.

To build trust, companies should focus on doing what they already do well and do it even better—and then draw attention to it.

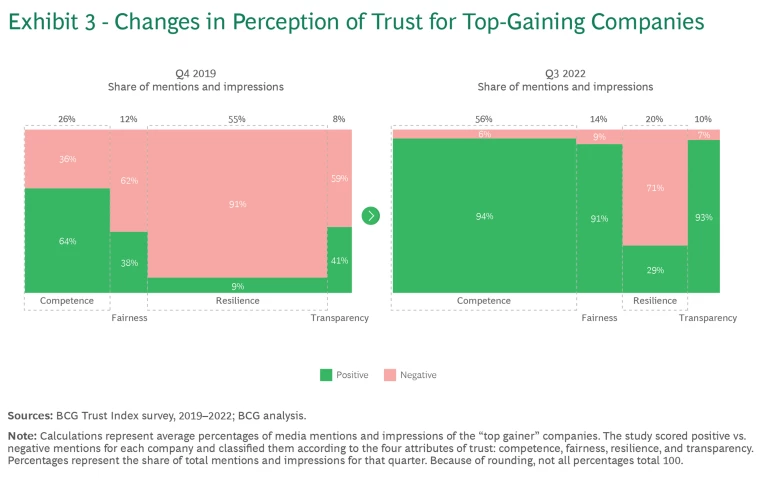

In short, these companies focus on doing what they already do well—and on doing it even better and then drawing attention to it. Our study, and the Trust Index research that preceded it, underscore how crucial competence-demonstrating actions are to building trust. We saw this in the discussions that we analyzed: positive comments tended to focus on competence, while negative comments focused on fairness, resilience, and transparency. Among the top gainers, 82% saw a significant uptick (more than 20 percentage points) in the relative share of positive discussion about their competence, compared with only 6% of the nongainers.

Consider one top gainer, a retailer (SundryCo) mired in public outcry after a price-fixing scheme and product recall. SundryCo had taken steps to address the price-fixing issue, including cooperating with authorities and bolstering its internal compliance processes. But the critical factor for regaining its former high-trust standing was a series of competence-proving actions. From 2020 to 2022, SundryCo made the news by launching a new health and wellness app, administering the COVID-19 vaccine, and achieving strong financial results. It also improved its core business operations and its ability to meet customer demands . These actions helped to allay concerns instigated by the product recall and demonstrated the company’s commitment to delivering high-caliber products and services.

Another top gainer, a transportation equipment manufacturer (TrainCo), was confronting a flurry of legal issues involving certification as a supplier. These issues were publicly associated with its failure to win an important contract and the breakdown of a planned merger. In response, TrainCo obtained relevant certifications rapidly and used them in court. It also used them in a PR campaign designed to show that it was a viable and trustworthy competitor. Then it revamped its internal compliance practices to demonstrate a more ethical corporate culture. These resilience-oriented efforts were vital to kickstarting the trust recovery process.

However, as with SundryCo, competence made the ultimate difference. TrainCo’s trust levels grew only after it signed a new contract with a major city and delivered the first set of products for a project abroad.

Over time, attention paid to competence is key to driving positive mentions and impressions in the press and social media. (See Exhibit 3.) For the top-gaining companies, M&I related to competence increased and the prevalence of resilience decreased during the three years covered by the study. This went hand in hand with a rise in overall positivity toward those companies, with mentions covering all four attributes: competence, fairness, resilience, and transparency.

Shifting attention from resilience to competence appears to be a universal factor in rebuilding trust. On a day-to-day level, it means less emphasis to stakeholders on the crisis and response and less focus on solving the problems and corresponding public relations. Instead, the top trust gainers double down on visibly delivering their core products and services.

Substantial gains in trust require some specific measures, often with a shift in behavior on the part of the CEO and senior leaders. They center on the following attributes:

- Resilience. Respond immediately and take responsibility. Tamp down current criticism and assure the public that you have already taken the steps needed to prevent similar issues in the future. Highlight the company’s commitment to delivering its stakeholder promises and restate your dedication toward fair and ethical behavior. Rapid response and empathetic statements reassure stakeholders that the company is on their side and dedicated to reversing negative outcomes.

- Competence. At the same time, strengthen and solidify the core business. Without renewed evidence of high-quality products and services and robust financial performance, companies in trouble cannot guarantee they will meet their commitments to their customers, employees, and shareholders. This will put them in a perpetual low-trust position. Continue to build on the company’s strengths with a broad array of actions and initiatives, so that being competent and trustworthy becomes a way of life.

The other two trustworthiness attributes, fairness and transparency, might seem equally important at first glance, especially when facing trust-destroying events involving bias, harassment, or unfair treatment of groups of people. However, in the empirical study, M&I of fairness and transparency did not emerge as key forces behind elevated trust levels. Rather, these attributes appear to be important for sustaining trust at a baseline level but less so for recovery. It’s primarily the levers of resilience and competence that enable companies to transform their positions from low to high trust.

Rebuilding Trust for the Long Term

Like the loss of trust, recovery isn’t linear. Some companies require more time or suffer intermittent losses on the way to recovery. In the study’s sample, one-third of the companies that experienced at least one trust-destroying event went through a second big loss after their initial decline. A few companies endured a third. This naturally made it more unlikely for them to recover quickly, or recover at all, within the period of the study. Only 24% were able to recover from a trust breach, representing about 7% of the full data set. (See Exhibit 4.)

One industrial raw materials company (MiningCo) came under fire in the national press for violating a policy to protect sacred land for Indigenous people. Its trust score declined substantially. The company began its bumpy road to recovery by fixing the problem and demonstrating competence. But two quarters later, a report was published on widespread sexual harassment of women in the mining industry. This caused a second big loss of trust—for both the company and its competitors.

Nonetheless, MiningCo began to rebuild trust through its competence, including an aggressive transition to green energy. This demonstrated that the company could outperform other mining companies in sustainable practices. Its score rose from -0.27 at the lowest point to 0.50 by the end of the observation period. Even so, it still had a 0.31 trust gap to close between its current lower level and its past.

These case studies highlight the often-turbulent journey to recovery. About 36% of the companies in the total data set went through dramatic ups and/or downs, experiencing either trust-destroying events (28% of trust breaches) or trust-creating events (10% of top-gainers). There was a 2% overlap: top gainers that recovered from a trust breach within the three-year period.

An in-depth analysis of this group—we call them the “turbulent path” companies—revealed three distinct archetypes of recovery, each with its own pattern of rising and falling trust. (See Exhibit 5.)

One path was marked by complacency. These companies seemed to take their recovery for granted, as if their restored trust would last indefinitely. But their trust levels fell again, often because of another incident that demonstrated either scandal or lack of competence.

ClaimCo was a case in point. As noted earlier, a management scandal drove its original high trust levels (0.72) down to 0.39. ClaimCo’s leaders put a great deal of effort into rebuilding the company’s trust level back up to where it had been before, and then stopped paying as much direct attention. However, as often happens, the aftereffects of the scandal continued to draw news coverage. ClaimCo’s trust level fell again back to 0.50.

Companies on a second path never fully recovered. These companies suffered a major trust breach and then reinforced that loss of trust with further missteps. They may eventually regain some trust, but not to the same level they had before. MiningCo and TechCo were among the “turbulent path” companies that followed this pattern.

MiningCo, TechCo, and ClaimCo have not yet been able to recover previous levels of trust; the same is true of 37 out of the 49 companies that suffered a major trust breach in the period.

The third path was traveled by 26 companies that suffered a major trust breach, rebuilt their trust back to preloss levels, and then sustained that recovery. These companies acted diligently and swiftly after the breach of trust. They focused on competence and resilience right from the start, repairing the holes in their reputation. Their scores rose substantially, albeit with occasional lapses along the way. TrainCo, rising from -0.43 to 0.68, and SundryCo, rising from -0.01 to 0.86, were two companies in this group. They both had very high CAGRs for trust throughout the three-year period.

A Strategy for Trust Advantage

What can we learn from companies that recovered successfully? And how can we develop and implement a systematic trust strategy before a crisis occurs? While the exact course to follow depends on trust drivers and other circumstances, there are some common actions every company can take:

- Actively measure trust levels. Measure and monitor trust levels regularly as a key metric for running the business. Always know where you currently stand and why. Track external forces that can materially or symbolically impact trust, and plan in advance how you might intercept them.

- Create a capability. Stand up a designated cross-functional team and process to manage trust continuously, in support of the top executive-management agenda. The team should be readily available to act in the event of a crisis or emerging issue or opportunity. This capability goes far beyond defaulting to the PR or risk department alone. Develop a fact-based, structured approach that can identify the causes of a loss of trust, act quickly on the resilience side, and mobilize to ensure perceived competence through action and word.

- Establish practices for continuously delivering on promises to multiple stakeholders. This is the heart of trustworthy competence. Double down on what you do well and make it known that your company is delivering value and quality in everything it does. Take steps to improve, ideally before a crisis happens, and even more so in its wake in a visible and discoverable manner.

- Consider the unexpected. Even if you are a key decision maker, you may not be immediately aware of all the factors that can lead to a trust crisis before it happens. Be ready for surprises. Develop a comprehensive crisis management plan and issue-interception agenda that outlines how to respond to various situations.

- Look for potential internal drivers of trust crises before they surface. Most trust breaches originate from within companies and are therefore avoidable. This may involve difficult or uncomfortable decisions that pit short-term interests with medium-term value and risk mitigation.

- Remain persistent, especially in delivering on competence. Constant vigilance is critically important; no company can sustain high levels of trust effortlessly. This entails a concerted effort of consistently and dynamically (re)articulating promises to key stakeholders that the company can actually deliver, as well as monitoring and ensuring that those promises are duly delivered over time—in other words, “walking the talk.”

When a trust-destroying event occurs, follow this sequence. First, visibly address the root-cause issue or commit to a timeline to addressing it. If the issue is severe, it may require frequent updates. Next, pivot to activities that demonstrate competence, to show that you are not paralyzed and are moving forward. Third, look for long-term measures that will, over time, demonstrate integrity (resilience) and competence.

Above all, establish a culture of integrity and make it part of your ongoing agenda. Don’t think of trust exclusively as a problem that needs to be solved, but as a positive path for growth and competitive advantage. When stakeholders have confidence in your company, they will work with you. It is helpful to know that trust, once lost, can be recovered. It is even more helpful—and worth a significant premium—to become one of the most confidence-inspiring companies in your field. You can then build a lasting trust advantage.

The authors would like to thank Primrose Ali, Wendi Backler, Anna Jiang, Santino Lacanna, Yago Soriano, Mahpari Sotoudeh, and Matt Williams for their help in the preparation of this article.