Global food systems are facing unprecedented pressures. Climate change is threatening the supply of food, while growing populations are increasing the demand for it. Meanwhile, food systems are themselves worsening the situation through their serious environmental and social impacts .

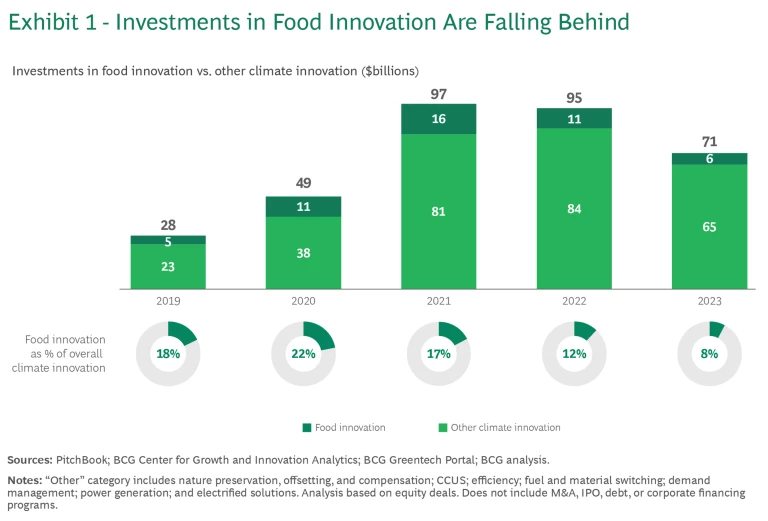

Innovation can mitigate these challenges—but only if that innovation is scaling sufficiently. Our analysis suggests that it is not. While global food systems are responsible for one-third of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, investments in food innovation—a strong indicator of scaling potential—account for a disproportionately small 8% of climate-tech investments.

“

Mainstreaming Food Innovation: A Roadmap for Stakeholders

,” by the World Economic Forum in collaboration with BCG, provides a framework for scaling food innovation using case studies from the WEF’s Food Innovation Hubs Global Initiative. With the proper mechanisms in place and strong cross-sector collaboration among stakeholders, we can make transformative and sustainable improvements in how food is produced and consumed.

Food Systems Are Struggling

By 2030, global food production will need to meet a significantly higher demand for calories, driven not only by a growing population but also increased per capita calorie consumption; as nations become wealthier, diets tend to shift toward resource-intensive foods.

On the supply side, the amount of arable land is decreasing by 1% per year, and more than 90% of global soils could be degraded by 2050, reducing overall food production by 10%. Making matters worse, about one-third of food produced for human consumption is lost or wasted.

While food systems are under environmental pressure, they also contribute to the problem, accounting for one-third of global greenhouse-gas emissions, 70% of freshwater use, and 80% of global deforestation.

While food systems are under environmental pressure, they also contribute to the problem, accounting for one-third of global greenhouse-gas emissions, 70% of freshwater use, and 80% of global deforestation. Food systems also fall short in securing the livelihoods of farmers—of the 700 million people living in extreme poverty globally, two-thirds work in agriculture.

In addition to their environmental and social impacts, food systems are failing at their most basic obligation: feeding the world. Since 2016, undernourishment has been increasing worldwide; today, 735 million people—nearly one in ten—experience hunger regularly. At the same time, 890 million people are obese. And many of those that are neither hungry nor obese still suffer from nutrient deficiencies, which affect an estimated one-fourth of the world’s population.

Innovation Offers Solutions—but It’s Not Scaling Fast Enough

Innovation can not only mitigate these challenges—it can help solve them. By 2050, for example, implementing regenerative agriculture practices could sequester 120 billion tons of CO2, three or four times the world’s annual emissions. Smart irrigation can reduce water use by up to 50% compared to conventional irrigation systems. By 2035, switching to plant-based alternatives for animal proteins could cut over 100 billion tons of CO2 and save 39 billion cubic meters of water—the annual water consumption of Germany.

Despite the potential impact, food innovation is not scaling relative to other climate innovations. While patenting activity shows that food innovation is occurring in line with general climate innovation trends, investments are not keeping pace. Exits are significantly smaller in food innovation: 20% lower for mergers and acquisitions and 40% lower for IPOs. Moreover, compared to climate innovation, food innovation experiences 40% less late-stage investment, which is crucial for scale.

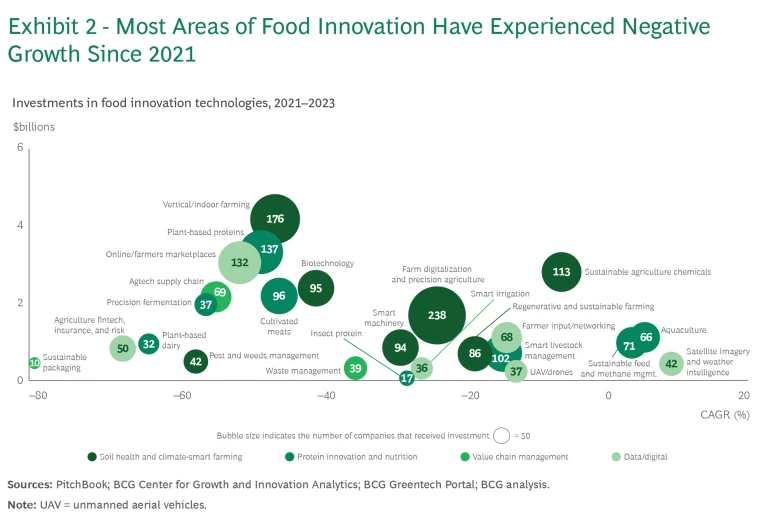

And the situation is getting worse. Since 2021, investments in climate innovation have been in retreat overall, but investments in food innovation have retreated faster. Whereas food innovation accounted for a quarter of climate-innovation investment in 2020, it’s now at only 8%—and falling. (See Exhibit 1.) Indeed, most areas of food innovation have seen investments fall from their 2021 peak. (See Exhibit 2.)

There are several reasons for this, including:

- Higher production costs, which lead to unfavorable unit economics

- A lack of supportive regulatory frameworks

- Consumers’ unwillingness to pay a premium for more sustainable options

- A lack of the basic infrastructure to enable innovations

If a mechanism can be designed that overcomes these barriers and leads to increased and better investment, then innovation in food systems can scale and reach its promised impact.

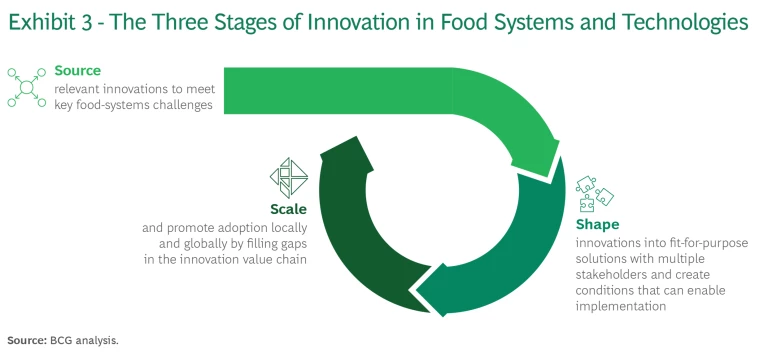

Before innovations can scale, however, they must be sourced and shaped. (See Exhibit 3.)

To illustrate the three stages of innovation, here are some examples from the alternative protein industry:

- Source. Cultured meat is currently in this stage—establishing proof of concept and overcoming initial technical difficulties. Key challenges for producers include developing reliable products, optimizing ingredients, and reducing the energy intensity of production.

- Shape. Plant-based meats are meeting consumer expectations in taste, texture, and nutrition. The shaping process, influenced by consumer feedback and interactions with key stakeholders from governments to financial institutions, ensures that products align with market demands and nutritional requirements.

- Scale. Plant-based milk has achieved significant market penetration and consumer acceptance. Producers have built economies of scale, enhanced distribution networks, and increased market share while overcoming challenges related to production costs, supply chain logistics, and competitive pricing.

Subscribe to our Climate Change and Sustainability E-Alert.

Building a Collaborative Ecosystem

The WEF’s Food Innovation Hubs aim to create ecosystems that address both general barriers and challenges specific to each stage of innovation.

The hubs form multistakeholder partnerships at the country and regional levels to promote innovations that are fit for purpose but not yet scalable. Hubs are currently being developed in Colombia, Europe, India, Africa, the United Arab Emirates, and Vietnam.

The Food Innovators Network links these hubs through a curated community of innovators and practitioners that facilitate global collaboration and the exchange of knowledge. The network organizes learning sprints on frontier innovations, focusing on underinvested areas or those requiring a coordinated scaling approach.

Lessons from these Food Innovation Hubs can be applied more widely, with stakeholders working together to build food-innovation ecosystems. Stakeholders can contribute by leveraging their unique strengths:

- Private Sector: Invest in and cocreate food system innovations, engage in partnerships, and promote sustainable business models.

- Governments: Facilitate long-term collaborations, provide regulatory and financial incentives, and support innovation infrastructure and funding.

- NGOs and Civil Society: Source and shape innovations with communities, act as intermediaries, and support local project implementation.

- Innovators: Develop and scale sustainable food solutions by engaging end users and seeking high-potential funding.

- Farmers: Codesign and implement innovations, adopt sustainable practices, grow alternative crops, and invest in technologies for sustainable production.

- Financial Institutions: Invest in food innovation systems, support hubs and research, and focus on long-term investments.

- Consumers: Promote and demand innovation through purchases, adopt sustainable diets, and advocate for regulatory changes to support food innovations.

The current investment shortfall is inhibiting the potential of food innovation to not only mitigate the negative environmental and social impacts of food systems but to become one of the most promising solutions in the fight against climate change. By unifying their efforts, coalitions of aligned partners can ensure that food innovations can deliver on their promise.