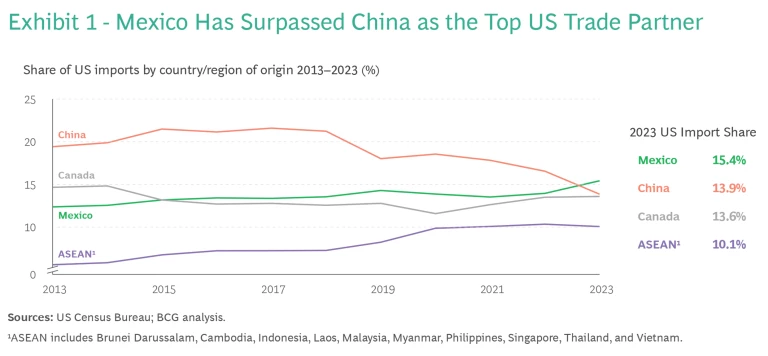

In 2023, Mexico surpassed China as the US’s biggest trading partner. The milestone reaffirms Mexico’s strengths as a production platform for the US and as a market for US exports. In the three decades since the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed, the combination of low labor costs, geographic proximity, and preferential market access has turned many Mexican states, especially those near the US border, into major manufacturing hubs. Big new factory investments are announced regularly.

But just as the momentum is growing, so too are potential obstacles that could undermine Mexico’s competitiveness. Labor costs are rising sharply. Skilled workers are in short supply in key sectors. New infrastructure isn’t keeping pace with the growing demand for electricity, water, and logistics, raising concerns over the reliability of Mexican supply chains.

Perhaps the biggest question is the scope of Mexico’s continued access to the US. Massive investments announced by Chinese auto OEMs are one reason the US may seek to renegotiate the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), the successor to NAFTA. Washington is concerned that the Chinese firms aim to circumvent high US protectionist barriers against low-cost Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) by assembling and exporting them from Mexico, taking advantage of its duty-free access under the USMCA. Both Democrats and Republicans have indicated they intend to keep that from happening.

Mexico remains the region’s best nearshoring option for many manufacturers. But those looking to build new factories must carefully evaluate the dynamics. Growing labor, infrastructure, and market access constraints could alter the calculus that indicates which part of Mexico is the best nearshore production option for certain industries and products—and whether it may be time to explore other countries in the region. These choices should be based on a fresh, holistic analysis that compares the manufacturing readiness and potential risks of different regions and industrial parks.

Mexico’s Manufacturing Momentum

Mexico’s manufacturing takeoff is still gaining steam. The country’s exports to the US reached a record $475 billion in 2023. (See Exhibit 1.) Manufacturing foreign direct investment (FDI) has risen by an average of 20% annually since 2019, compared with 7% globally, as companies from Germany, Canada, Japan, and other nations expand or shift production targeting North American markets to Mexico to diversify their global supply chains. Two dynamics—rising costs in China and Washington-Beijing trade tensions—are driving this trend.

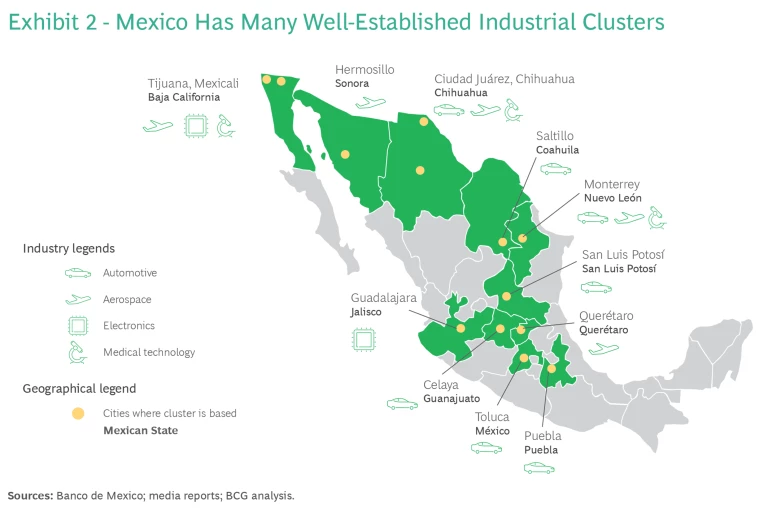

Sizable industrial clusters with extensive networks of component suppliers have developed over the years in different parts of Mexico. Baja California, for example, has well-developed clusters in electronics, aerospace, and medical products. Nuevo León, San Luis Potosi, and Puebla have some of the largest concentrations of automotive manufacturers. Chihuahua is well established in advanced manufacturing. (See Exhibit 2.) New clusters are forming: medical technology manufacturing, for instance, is expanding from the current core hubs of Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez to new locations, such as Monterrey and Hermosillo.

The automotive sector, where investment nearly doubled to an estimated $8.5 billion in 2023, has accounted for 40% of that FDI. Investment in supplier industries, such as steel, auto parts, and electronics, is also rising. Automotive technology giant Aptiv, for example, has been continually investing in Mexico, where it employs an estimated 77,000 people—some 40% of its workforce.

EVs are driving a new investment burst. BMW and Volkswagen have announced major expansions of their facilities in San Luis Potosi and Puebla, respectively, to make EVs. Tesla has said it is considering a factory in Nuevo León. Chinese OEMs intend to come as well. Jetour unveiled plans for a $3 billion investment to make both EVs and gasoline-powered cars; BYD Company says it intends to build a Mexican factory that could create 10,000 jobs. SAIC’s MG Motor has also indicated it is looking to enter Mexico. China’s Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL) is considering a multibillion-dollar battery factory, and China Steel is exploring a $400 million mill in northern Mexico.

Manufacturing Advantages and Headwinds

Mexico has several big advantages as a nearshore production platform for the US. But investors will also need to consider headwinds that could erode some of Mexico’s relative competitive edge in several areas.

Labor. Mexico has both low labor costs and a young workforce. Fully loaded manufacturing labor costs range from $6 to $8 an hour including bonus and benefits. Roughly one-third of the country’s population, some 42 million people, is 19 or younger.

Mexico’s labor market is showing signs of overheating, however. Factory wages have been rising fast: the national minimum wage has climbed by an annual average of 20% since 2019. Mexico still enjoys a big labor cost advantage over the US and even China. But it’s been losing cost-competitiveness against Southeast Asian nations that compete for manufacturing work in industries like electronics and medical technology products.

Skilled labor is also growing scarce and more difficult to retain. Mexico’s unemployment rate was only 2.7% in 2023’s final quarter. Labor shortages are particularly acute in the north and among skilled trades such as welding and facilities maintenance. These shortages affect an estimated one-quarter of Mexican firms, according to the business organization Coparmex. Attrition rates among blue-collar workers have approached 60% at some factories as companies intensify competition for talent by offering perks such as retention bonuses and free health clinics, transportation, and meals. Companies increasingly operate their own training programs to compensate for limited curricula at Mexican schools.

Subscribe to our Industrial Goods E-Alert.

Ambitious labor reforms under consideration are likely to further tighten the Mexican labor market. In June 2024, the ruling Movement of National Regeneration party, known as Morena, won the presidency in a landslide and gained a supermajority of two-thirds in the federal legislature’s lower house and now controls 24 of 32 state governments. It is now in a powerful position to implement its workers’ rights platform. It has proposed reducing the workweek from 48 hours to 40 while maintaining equal pay levels. The government also proposes extending maternity and paternity leave and requiring year-end bonuses equal to as much as 30 days in wages.

The USMCA, which has provisions to protect workers’ rights in North America, is compatible with these changes. But if all these measures are implemented as proposed, BCG projects that they will increase Mexican manufacturing labor costs by 10% to 20%. Such a cost increase should be measured against rising labor costs in the US, driven in part by recent United Auto Workers contracts with the Big Three and others. This will, in effect, preserve some of Mexico’s labor cost edge.

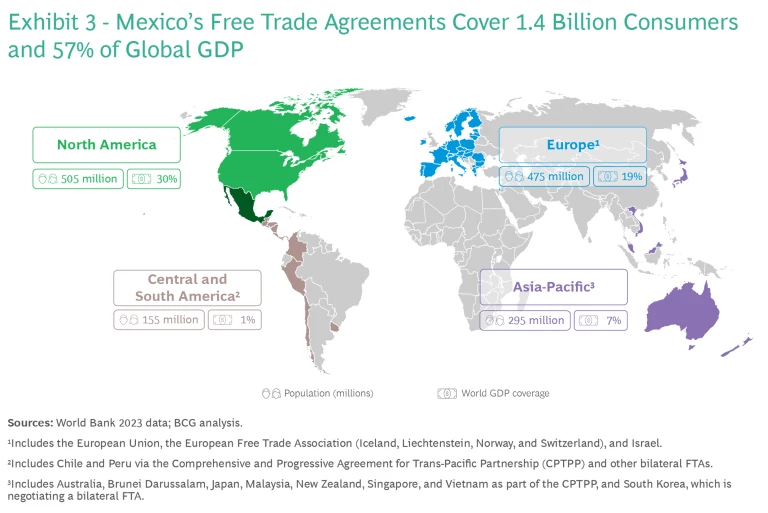

Preferential Market Access. Mexico boasts some 30 free trade agreements with nations that account for 57% of the global economy. (See Exhibit 3.) The most important of these is the USMCA, which enables most of its goods to enter the US and Canada tariff-free or with minimal duties. The pact also gives Mexican factories duty-free access to equipment, components, and materials imported from the north of the border—a beneficial arrangement for all countries.

The growing Chinese investment presence in Mexico, however, has raised new questions about the future trade relationship with the US. Although Chinese auto OEMs have said their planned Mexican factories are primarily aimed at supplying Latin America, US officials question whether the real motive is to export inexpensive EVs north of the Rio Grande River to circumvent current US restrictions on Chinese-made autos.

In May 2024, President Joe Biden imposed a 100% duty on Chinese EVs, clean energy products, and semiconductors under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. Already, Chinese EVs did not qualify for US dealer-floor subsidies under the Inflation Reduction Act; these incentives apply only to vehicles built in the US, Mexico, and Canada. Under current USMCA rules, however, passenger cars assembled in Mexico with a high amount of materials and parts sourced from within the region can enter the US duty-free. Even if they don’t meet US content requirements, passenger cars assembled in Mexico would only be assessed a duty of 2.5% under the US’s World Trade Organization commitments. (The corresponding duty on light trucks, including pickups, is 25%.) In other markets, Chinese EVs have been very price competitive. In Europe, for example, the average Chinese EV costs about $52,000, compared with $72,000 for non-Chinese EVs. In India, Japan, and Southeast Asia, Chinese EVs average less than $30,000. Because US OEMs do not offer low-cost EVs, US politicians and labor unions fear China could quickly dominate the US market—and potentially derail efforts to build a competitive EV industry in North America.

Chinese industrial expansion so close to the border has become a hot issue in US politics. The Biden Administration has already reached an agreement with Mexico to allow the US to monitor foreign investment in that country. Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump has pledged a 100% tariff on Chinese cars imported from Mexico. In 2026, any of the three USMCA countries could trigger its renegotiation; Democrats have indicated they intend to do so.

The US would have considerable leverage in any future USMCA talks. It is North America’s biggest market, and its economy is less dependent on exports than those of Mexico and Canada. If the US can negotiate stricter import rules on Mexican products entering the US or on foreign investment into Mexico from third countries, it could diminish Mexico’s allure as a manufacturing location. So far, US politicians have not called for scrapping the USMCA. It was a marquee trade policy achievement of the Trump Administration and ratified by a labor-friendly, Democrat-controlled House of Representatives. Both Canada and Mexico want to preserve the USMCA, too. In fact, new elements may be added, reflecting economic changes since the previous renegotiation began in 2017. Whatever happens with the USMCA, Mexico retains other free trade agreements that provide preferential access to the EU, Japan, and other large markets.

Logistics and Infrastructure. Mexico’s unique advantage as a nearshore manufacturing platform is its 2,000-mile border with the US, with 48 road and five rail crossings. That makes it easy for goods shipped from many efficient industrial clusters across Mexico to reach nearly all parts of the US in one or two days.

Mexico’s transportation infrastructure is strained, however. The nation ranked lowest among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries in the 2023 World Bank Logistics Performance Index. Key problems include long wait times at US border crossings, a lack of real-time tracking, and frequent theft.

Industrial land is growing scarce and more expensive, especially in the north, where vacancy rates in industrial parks generally range from 1% to 3%.

Mexican utilities are also under stress. Electricity costs an average of 18 cents per kilowatt-hour, roughly double the rates in the US and China, owing to underinvestment in the energy sector. Renewable energy sources are limited and riddled with complex regulations. Water scarcity is another urgent challenge, particularly in northern industrial states. Although $2 billion in water infrastructure projects is planned, progress has been slow.

Even with these pressures, however, no other Latin American or Caribbean nation can come close to matching Mexico’s logistical advantages. Shipping goods by land or sea from most other manufacturing zones in the region typically takes at least two weeks.

An Approach to Assessing Nearshore Locations

Given the shifting dynamics, identifying the best nearshore production site for a US company requires a comprehensive competitiveness analysis, focusing on different locations within Mexico and elsewhere in the region. We suggest the following approach.

Clarify the scope and ambition of the production transfer. The first factors to consider are the company’s overarching expectations for cost savings and delivery times—and its tolerance for risk. Companies should determine the labor requirements for manufacturing the products and which production processes will be used. If high degrees of manual, moderately skilled labor are needed, low labor costs may be more important than they would be in cases where production lines are largely automated. The complexity of the supply chain and whether key suppliers need to be close to assembly plants are additional key considerations. How quickly must the finished goods be able to reach different parts of the US?

Identify the right Mexican state and city. Each Mexican state has pros and cons as a manufacturing location, depending on the industry and a company’s specific needs. The analysis should include the area’s macroeconomic stability, workforce dynamics, transportation infrastructure, supplier networks, and utilities availability and price. The 43 free trade zones along the US border offer low taxes and the fastest and easiest access to US markets, for example, but wages tend to be about 50% higher than in the rest of the country, and job hopping is more frequent. The state of Nuevo León offers economic stability, an extensive supply base, and efficient road and rail connections to the US. Among Querétaro’s advantages are excellent transportation links and public safety.

Look beyond Mexico to Central America and the Caribbean. Given Mexico’s rising labor costs and uncertainties over US market access, it may be time for some companies to also explore other nearshore options. In industries that require scale, extensive local supply chains, and efficient logistics (such as the automotive industry), there is essentially no low-cost nearshore alternative to Mexico for serving the US market. In other industries, however, viable options may be available in Central America and the Caribbean.

Take medical devices. Costa Rica, whose fully loaded labor costs are comparable to Mexico’s and whose factories are generally union-free, exports approximately $5 billion worth of medical devices a year. Costa Rica has a higher unemployment rate than Mexico—an indicator of available labor—along with a better-educated workforce and far lower employee turnover. It also has a good local supplier network in this industry.

Labor costs in the Dominican Republic, which exports some $1.5 billion in medical devices a year, are one-third lower than in Mexico. But the Dominican Republic’s supplier base is less developed than Costa Rica’s.

But because it takes at least two weeks for devices shipped from Costa Rica or the Dominican Republic to reach most points in the US, Mexico also still has a huge logistical advantage unless the goods are small enough and valuable enough to be transported by air freight.

Pinpoint the location with the right operating environment. After settling on a Mexican state or an alternative country, a company should develop a short list of four to six industrial parks or specific sites meeting its criteria. A holistic assessment of each site will determine its maturity as a manufacturing zone and its level of operational risk . Potential cost savings should be weighed against how well prepared that location is to deliver good results. Which location or specific industrial park offers the best access to talent, suppliers, logistics, and services? If a factory needs to quickly ramp up production to meet growing demand, will local suppliers be able to boost output as well? Is there space to expand, if needed? Companies should validate whether there will be enough energy and water to meet current and future needs. Working with national, state, and local government agencies will reveal the requirements for receiving grants and other incentives—and how long it will take to receive necessary regulatory approvals.

Companies should develop model profit-and-loss estimates for different locations considering all the key variables, such as specific USMCA provisions, labor rates, energy prices, and currency fluctuations. From a return-on-investment perspective, they should calculate the capital expenditure needs and the net present value over the investment’s lifetime and factor in incentives offered by national and local governments. Locations with existing clusters in similar industries will likely offer a better supply of labor with specific skills and local supplier networks.

As a nearshore production platform for the US and Canada, Mexico is unrivaled for many industries that require both low costs and speedy time to market. But the dynamics that have defined Mexico’s competitiveness since NAFTA was signed in 1994 are now in flux. Manufacturers that conduct a holistic analysis of different locations in Mexico and compare them with other options in the region can still gain a strategic advantage. But it will require a new calculus of cost and risk and close attention to evolving trade arrangements.