Transformations are tough under any circumstances, but they’re even harder in the defense context. Leaders often underestimate the complexity of the effort required, particularly in terms of culture and people development . Defense enterprises must maintain mandatory readiness levels and security responsibilities, so they cannot shut down operations to execute a major change program. And cultures can be conservative: favoring legacy models over innovation, stability over experimentation, and consistency over diversity.

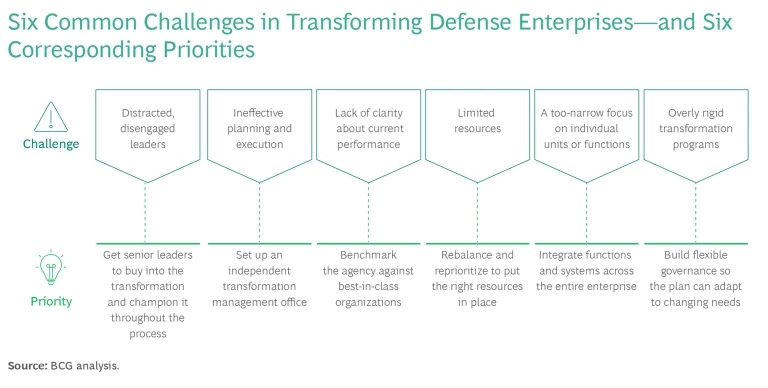

Yet with the right approach, defense agencies can overcome these challenges and launch successful transformations that leave them better equipped to fight and win in the future. Based on our extensive work helping these organizations around the world implement large and complex change efforts (this is the second article in an ongoing series about transforming defense agencies; the first discussed the core elements that leadership teams must address in a transformation ), we have identified the six biggest challenges affecting defense transformations, along with a corresponding priority for each. (See the exhibit.)

Leadership Buy-In

Challenge: Distracted, Disengaged Leaders

A key reason why many defense transformations fail is that leaders aren’t aligned on the aims of the project, the implementation approach, or how to deliver impact at every level of leadership. In one extreme example, a defense organization launched more than ten transformation attempts, each stalling out or canceled before implementation due to these dynamics. At times, these derailments occur when individual leaders willfully fall out of step with the rest of the organization. Such situations require top leadership’s involvement to course correct and get transformations back on track.

Priority: Get Senior Leaders to Buy Into the Transformation and Champion It Throughout the Process

The first key success factor for a successful transformation is senior leadership buy-in. Leaders must understand the need for change, support the implementation process, and take accountability for results. Moreover, they need to communicate clearly and frequently about the overarching vision and how the organization will benefit. This is especially important once the process is set in motion. Change is stressful, programs invariably hit bumps along the way, and doubts arise about the necessity and effectiveness of the program. Consistent communication and enthusiasm from leaders can alleviate these doubts and keep the program moving forward.

Planning and Execution

Challenge: Ineffective Planning and Execution

Defense agencies are complex organizations with multiple missions, capabilities, cultures, and even leaderships structures. This complexity is only increasing as defense agencies have a wider defense and security mandate. For example, ministries of the interior typically include police, border guards, and civil defense, among other entities. Running these organizations on a day-to-day basis is a challenge, let alone transforming them—all while retaining a strategic focus on a country’s overarching defense and security goals.

Priority: Set Up an Independent Transformation Management Office

Given their complexity, defense organizations each need an independent transformation management office (TMO) to oversee the change program and keep it on track. (Some entities use different terminology; for instance, a change management office or strategic design authority. We use TMO here for the sake of brevity.) The TMO’s main roles are to manage, monitor, and enable the transformation and to provide independent assurance to leaders about the overall status. Specifically, the TMO develops a roadmap with key timelines and milestones. The roadmap also defines interdependencies so that leaders can sequence specific projects and components to avoid bottlenecks. It should also plot interdependencies with other change management efforts across adjacent defense and security entities, as well as those with international allies and partners.

Several aspects of the TMO are worth noting:

- TMOs need the right mandate, structure, and authority, underpinned by a strong governance structure. They should be empowered to hold unit leaders accountable to achieve specific targets and be explicitly responsible for strategic management, project management, and change management .

- TMO leaders and teams need the right skills and expertise, along with cross-functional representation. The function must be fully staffed with dedicated talent (not people taking it on in addition to their regular responsibilities). Some agencies reassign their own people, while others seek external support.

- The TMO is responsible for guiding and supporting the implementation of the transformation, but it is equally responsible for making performance transparent. Successful TMOs keep the leadership team continually informed of overall project status, along with any issues that require them to intervene. Determining when to escalate critical decisions to senior leaders is a core part of the TMO mandate.

Clarity

Challenge: A Lack of Clarity About Current Performance

To succeed in a transformation, a defense agency needs an honest and objective view of its own performance and its ability to achieve the intended outcomes. It must know where it currently stands to determine how best to move forward.

Priority: Benchmark the Agency Against Best-in-Class Organizations

A benchmarking exercise—complemented with an internal baselining exercise—can bring needed clarity. By comparing its performance with that of other nations, a defense agency can understand where its biggest challenges and issues lie. Critically, benchmarking can also identify specific measures that other organizations have taken to address those gaps. In that way, defense enterprises can compile potential solutions and understand the outcome of these efforts.

By comparing its performance with that of other nations, a defense enterprise can understand where its biggest challenges lie.

Of course, each body faces its own national strategic circumstances, decision authority systems, resource constraints, and financial and legal regulations, among other factors. Solutions aren’t universally applicable: they must be tailored to meet the specific circumstances of the individual organization.

In addition, choosing benchmarks from too many countries—or countries that are markedly different—can be counterproductive. For that reason, it’s critical to determine the right organizations to benchmark and which of their specific elements are worth considering. One approach is to set up reference groups—teams that focus on one function within the agency and can use their expertise to determine which countries could provide the most relevant benchmarks.

Resources

Challenge: Limited Resources

Transformations take time and money, and defense organizations must ensure that sufficient resources are available. Understanding resource limitations in advance will help clarify the agency’s capacity to support transformation while still conducting its routine business.

Priority: Rebalance and Reprioritize to Put the Right Resources in Place

Defense enterprises can address personnel resource constraints by upskilling internal employees and recruiting top external talent—either as full-time employees or as contractors for the duration of the project. They can also temporarily reassign existing staff to the transformation team, which means that leaders have to make difficult choices about which outcomes cannot be delivered or where lower standards must be accepted during the transformation period. This requires a realistic understanding of enterprise-level risk—including the opportunity cost of reassigning top talent for a defined period—along with clear communication to the government.

Leaders must make difficult choices about baseline requirements for the organization. This demands an understanding of enterprise-level risk—along with clear communication to the government.

Funding constraints are often more challenging to deal with. In some cases, transformation programs are funded via a separate budget allocation. But very often they are covered within existing budgets, putting additional requirements into day-to-day schedules, annual work cycles, and resourcing decisions.

Additionally, leaders will almost certainly need to reallocate assets in the course of the transformation. These are long, complex projects, and over the many transformations we have supported, agencies frequently need to rebalance and reprioritize talent, capital, information, and other resources across the project timeline. For example, when a transformation moves from the design phase into implementation, new subject matter experts are often needed—people who have more extensive implementation experience relating to specific functions and can troubleshoot inevitable issues.

Similarly, even carefully designed budgets often need to be adjusted over the course of a multi-year transformation. The costs, duration, and scope of individual projects and initiatives in the broader transformation frequently change owing to real-world factors that were impossible to predict. Economic factors, such as unanticipated inflation that pushes up the price of goods and services, can impact budgets as well.

For example, as part of its Green Book business case methodology, the UK government recently revised its budgeting and approval processes to be more agile and flexible. Requirements are now more fluid at earlier stages of a major transformation program, with teams able to access the capital they need for proofs of concept and pilots. The results of those initial stages then inform how the remainder of transformation funds should be allocated.

Focus

Challenge: A Too-Narrow Focus on Individual Business Units or Functions

Another common challenge we see in defense transformations is a focus on bottom-up efforts—particularly to address individual functions such as IT, HR, finance, or procurement . Those efforts may improve performance within a specific function, but a siloed approach risks creating a collection of divergent, isolated functions with unconnected systems and processes, akin to renovating a house one room at a time.

Priority: Integrate Functions and Systems Across the Entire Enterprise

To avoid this fragmentation, a better approach is to execute a transformation at the overall enterprise level, with all functions, systems, and activities integrated and aligned around the final vision. To do so, agencies need to set overarching design principles and a holistic, high-level blueprint of the end state organization, along with robust implementation governance. They need to determine how the many units and functions of the organization should work together based on a clear view of the overall goals.

Critically, our experience in supporting defense enterprise transformations has highlighted the importance of horizontal alignment. Bringing together stakeholders from various functions and departments can foster cross-functional coordination and collaboration, reduce the risk of miscommunication, and ensure that all team members are working toward the same goals.

In addition, partnerships with industry can help agencies develop complex new capabilities. For example, the South Korean government has created innovation clusters that partner defense entities with private-sector players to build up the workforce and improve their proficiency in advanced technology. Similarly, the Five Eyes intelligence alliance of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK, and the US includes a component to generate new workforce capabilities in electronic warfare and mission data.

Flexibility

Challenge: Overly Rigid Transformation Programs

For understandable reasons, defense agencies often want a well-defined plan in place at the outset of a transformation. But an overly rigid plan can itself be a problem. Inflexibility in a transformation blocks the adoption of new ideas, stifles learning, and prevents adjustments in response to changing circumstances. It inhibits innovation and enthusiasm and ignores ideas at all levels of the organization that could streamline processes or improve performance.

Agencies often want a well-defined transformation plan. But an overly rigid plan can be a problem.

Priority: Build Flexible Governance So the Plan Can Adapt to Changing Needs

Defense agencies should build flexibility into a transformation, with the expectation that the project will adapt over time. A flexible governance model allows for experimentation and learning through trial and error to identify new ideas and apply lessons learned. The recent US National Defense Industrial Strategy—which focuses on cybersecurity, acquisition and supply chain readiness, and workforce preparedness—includes this kind of governance, with a more structured approach for long-term piloting, testing, and scaling of various initiatives.

In fact, in the current environment of accelerating change, the best defense enterprises develop a culture of constant evolution and improvement. They review and transform on an ongoing basis, constantly assessing the future strategic environment, identifying the factors that must change as a result, and developing options for how to implement that change. This ability to forecast requirements sets modern defense enterprises apart from those that can only react to imposed change.

For that reason, robust defense organizations don’t entirely shut down the TMO after a major transformation is concluded but embed some form of that function into their workforce. That way, they stay nimble and maintain a constant drive for excellence.

In a rapidly changing world, defense enterprises must change as well. Through the six elements discussed here, these agencies can successfully transform to improve their performance, adapt to changing circumstances, and ultimately fulfill their mission more effectively.