As governments grapple with postpandemic economic realities, the pressure to balance fiscal responsibility with delivering excellent public services has never been greater. The pandemic and its aftermath essentially took costs off the agenda for the last four years. Out of necessity, governments ignored current debt loads and ratcheted up fiscal stimulus to meet pandemic-related needs, offset lost tax revenue, and avoid layoffs. Now, missed revenue forecasts loom large, and governments face big shifts and new expenditure priorities. These include aging populations, rising expectations for digital services, difficulties hiring and retaining staff, deteriorating infrastructure, and accelerating climate change.

Governments need to reset on both cost and service. The good news is that our latest client experience shows that governments can indeed spend smarter and serve better, making real progress on cost reduction in both the short-term and long-term while simultaneously improving services for constituents.

- Governments and agencies that engage in strategic cost optimization can recoup 10% of costs—or more—on a whole-of-government basis using existing tools.

- The size of the opportunity balloons to 25% to 35% of costs, without contemplating job loss, when we consider applying new technologies such as AI and generative AI to specific functions and agencies over an extended time horizon (10 years and beyond).

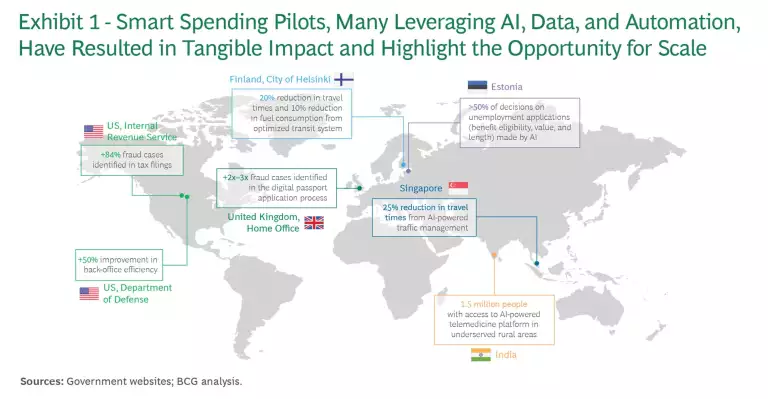

Achieving this level of savings, which includes immediate cuts and a long tail of cost reductions to be unlocked in the future, is possible across geographies, agency types, and functions. Savings can be realized by all manner of institutions, from local government social services agencies to national defense ministries. (See Exhibit 1.) The spend-smarter-and-serve-better approach offers solutions to the age-old question of how to do more with less.

From Spending Missteps. . .

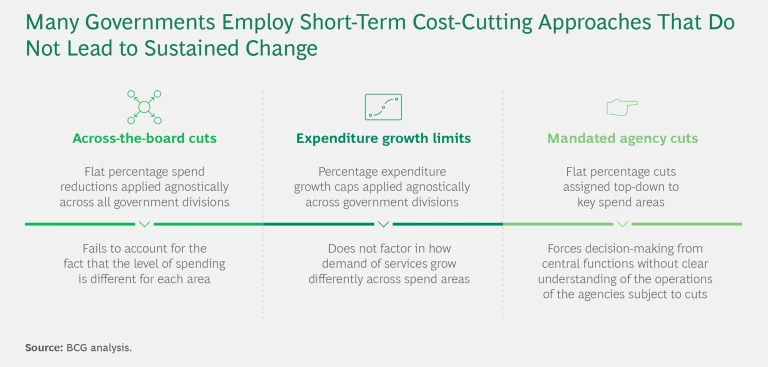

Governments have typically employed three techniques to constrain expenditures: across-the-board cuts; capping cost increases or applying a flat growth line across all areas of spending; and mandated agency reductions. (See “Three Spending Missteps.”)

Three Spending Missteps

(See the exhibit.)

The first approach is applying across-the-board cuts, which appeals to senior leaders because the reductions appear to be “fair,” and treating everybody equally sidesteps upfront political cost. In fact, this approach creates more challenges down the road as spending is not equally distributed across constituent needs. Across-the-board cuts fail to account for spending variations across agencies and functions and frequently don’t end up implemented as originally intended, often leading to large setbacks in important policy implementation.

The second approach is capping cost increases or applying a flat growth line across all areas of spending. This is a forward-looking version of across-the-board cuts, and it is no more effective. It does not consider the changing needs of citizens and businesses and frequently stifles innovation by killing the investment budgets of the affected agencies. It also leads to deferring critical investments that eventually end up costing more, such as cutting funding for preventative mental health services, which leads to adverse outcomes and more expensive services down the road.

Third are mandated agency reductions: flat cuts assigned to specific functions or agencies. These cuts typically result from decisions to limit expenditure in a single area, such as health care or education. They are divorced from a thorough understanding of the affected operations and do not try to make rational adjustments.

Unfortunately, all these efforts involve rigid decisions that may not recognize the individual context of each agency or program. Such decisions often lead to reductions that result in negative consequences for constituents or cuts that control costs only in the short term. Ultimately, such efforts are ineffective, but the alternatives (raising taxes and borrowing) are either politically unpalatable or, in many jurisdictions, proscribed by law.

In addition, these efforts to manage budgets often cut programs that are working well and shift resources to efforts that are not sustainable. They focus on near-term spending but do not address the underlying drivers of increased cost or force real conversations about the types of services that are being provided. Agencies end up trying to do the same amount with less funding instead of stopping things that they shouldn’t be doing in the first place.

. . .to Spending Smarter

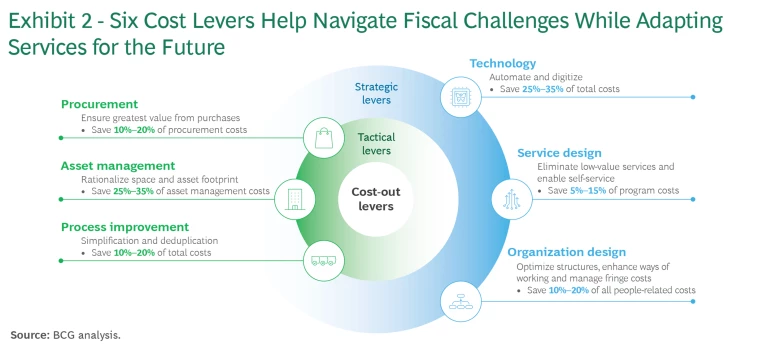

Our approach to spending smarter and serving better embeds strategy into reducing costs and improving services from the get-go. (See Exhibit 2.) It involves moving quickly to pick the low-hanging fruit—procurement costs, better asset management, and process improvement—which buys time and provides immediate cash savings to fund longer-term strategic changes in service design, organization design, and technology.

Procurement. Many governments and their agencies put too much focus on regulatory compliance and not enough on the value of what they are buying. Purchasing, which can represent 30% to 50% of total spending, is rarely centralized (except for regulatory oversight), meaning governments do not take advantage of their substantial scale. It’s common for different agencies to pay wildly different prices for the same commodity. In addition, processes are led by agency teams with limited scale and capabilities. By negotiating better terms on contracts or combining purchases, agencies can save as much as 10% to 20% of procurement costs and improve support to government departments. One US state realized its negotiated rate for computer monitors was 20% higher than purchasing the same monitor at a consumer electronics store. Locking in these savings requires procurement model reform—and often greater centralization—which can be politically challenging, but the level of ongoing savings justifies the effort.

Asset Management. Decentralization is again an issue; most governments do not reap the advantages of scale in areas such as real estate. They also hold on to old-fashioned space-inefficient practices (such as big individual offices) that inhibit collaboration. Many need far less office space postpandemic. By better organizing real estate assets and other physical resources, governments can improve interactions with the public and make work environments better for staff while saving 25% to 35% of asset management costs.

Process Improvement. Limited investment budgets, slow adoption of new technologies, and general resistance to change are common problems, as are overly prescriptive legislative or regulatory rules that mandate processes be done in certain (typically inefficient) ways. By simplifying complicated procedures, adopting proven change management techniques, and making the transition to modern technologies, governments operate more cost-effectively and free up staff time for work that improves service and satisfaction. We find that these changes also significantly improve the user experience because the government has taken the “sludge” out of the processes. They can cut costs by 10% to 20%.

Service Design. Redesigning service delivery allows governments to achieve the same outcomes while saving 5% to 15% of program costs on average. This can be done even while reforming services to be more resilient in the face of changing demographics (including aging and migrating populations), increased demand for digitization, and future proofing against global risks, such as climate change and political and economic instability.

Governments can meet these service-design challenges and reduce costs in three ways:

- Rationalize programs to meet shifting demand and simplify overlapping services (such as consolidating programs that spend money to achieve the same outcomes).

- Use lower-cost program designs without compromising constituent experience (such as shifting long-term care from institutional settings to home-health models).

- Adopt alternative delivery channels and touchpoints (by using third-party delivery, for example) to lower cost and increase constituent accessibility.

Organization Design. The aftermath of COVID-19 highlights significant challenges for public agencies in retaining and managing their workforce, which puts immediate stress on service delivery and inhibits adapting quickly to new work models. But strained organizations also provide opportunity for reform. The breadth and depth of bureaucracy slows decision-making and increases managerial costs. Government leaders need to review the management structures of their areas of responsibility, including headcount, time spent on low-value work, and working with nonprofits and the private sector to deliver programs.

Talent is often managed inefficiently, with slow vacancy fulfillment and inadequate incentives for promotion and retention. Slow hiring timelines mean that governments lose their first-choice hires (they take other jobs) and can become reliant on expensive contractors. Simplifying recruiting, establishing clear career paths, and adopting cross-functional ways of working can improve both service delivery and staff engagement. Streamlining cross-agency coordination through centralization and consolidation can further improve service while reducing cost.

Government departments and agencies can redesign organization structures to reduce complexity and duplication of effort while also managing people-related costs, such as overtime, workers’ compensation, and the cost of replacing workers who leave government service. Such moves improve interactions with the public or businesses and can save 10% to 20% of all people-related costs, even without changing the number of employees, according to our estimates.

Technology. Three factors drive the need for governments to invest in technology today. They need to keep pace with fast-evolving constituent expectations that are largely shaped by innovations in the private sector. Limited government staffing cannot match the growing demand for services, which is further exacerbated by an aging and diversifying population. Legacy infrastructure incurs increasingly high maintenance costs and limits technological agility. Service inefficiencies and cyber risks are fast-rising concerns.

In addition, AI and generative AI are still in their early days of government usage, but they are expected to create significant opportunities for both cost reduction and service improvement down the line. (See “Doing More with Tech Platforms.”)

Doing More with Tech Platforms

Digitizing Interactions. Online portals and mobile apps can be used to create AI-enhanced digital channels that adapt to user preferences for streamlined service. Virtual assistants use AI-driven chatbots for 24/7 assistance, reducing wait times and improving accessibility.

Automating Processes. Governments and agencies can automate data entry and document categorization with AI, increasing accuracy and efficiency. Predictive analytics use AI to forecast resource needs and policy outcomes, optimizing planning. Workflow automation programs integrate AI to manage task routing and approvals, ensuring efficient and compliant operations.

Upgrading Systems. Data integration platforms use AI to consolidate and integrate data across systems, enhancing decision-making capabilities. AI can enhance cybersecurity by deploying real-time threat detection and security measures. Smart infrastructure involves upgraded infrastructure for improved efficiency and responsiveness.e mandated agency reductions: flat cuts assigned to specific functions or agencies. These cuts typically result from decisions to limit expenditure in a single area, such as health care or education. They are divorced from a thorough understanding of the affected operations and do not try to make rational adjustments.

We see three ways that governments can better integrate technology into their processes:

- Digitizing Interactions. Adopting digital channels can significantly reduce service costs and improve accessibility.

- Automating Processes. Automation can alleviate workforce shortages and allow workers to focus on more complex needs.

- Upgrading Systems. Modernizing outdated systems can decrease maintenance costs and foster the adoption of innovative technologies.

All told, upgrading systems can help improve user experience and enable staff to do more with the same resources. Potential savings are in the range of 25% to 35% of total costs.

Spending Smart in Practice

We are starting to see more governments implement the spend-smart, serve-better approach. For example, take one US state that experienced increases in spending despite a decline in overall population and wanted to reduce taxes and regulation. It identified more than 30 initiatives to eliminate complexity across 13 departments. The initiatives eliminated close to 10% of general fund expenditures. They included an overhaul of the procurement to reduce wasted expenditure through centralized negotiations and demand planning, and the streamlining of multiple approval processes to reduce the departments’ administrative burden. Services were reengineered to be more cost-effective and better-aligned with constituent needs. Initiative such as shifting health care reimbursement to encompass more home care in lieu of long-term care facilities both cut costs and improved services.

With similar goals, a European country mapped out key areas of government improvements for the next five years. This whole-of-government effort constructed multiple initiatives that drew on collaboration across various departments, including simplifying rules and increasing autonomy in public agencies; streamlining organizations across state, regional, and local governments, with focus on administrative efficiency; and driving a digital transformation centered around generative AI’s potential to improve efficiency, quality, and labor productivity. The initiatives represent potential annual savings of $1.7 billion to $5.4 billion a year.

Six Principles for Success

For governments such as these, adhering to six principles can redirect spending miscues to smart cost-optimization moves and avoid slipping back into short-term thinking and worrying about possible adverse ramifications.

- Set clear objectives. Define an unambiguous goal for the overall cost-campaign (such as dealing with a crisis, reducing burdens on constituents, or expanding services) and stick to it.

- Focus the impact. Bring a strategic approach to systematically target the amount of savings across each agency, function, or budget line, instead of applying flat cuts. This means translating the overall cost saving objective into individual component reductions for each agency or program.

- Attack the problem from multiple angles. Go beyond top-down benchmarks and work with each affected organizations from the bottom-up to develop insights and targets from internal data and conversations.

- Look beyond spending and to outcomes. Assess overall value of services (to constituents and to government itself) to ensure the best return-on-investment using the most cost-effective methodologies. Take a comprehensive approach to consider future savings and promote investments in opportunities for service improvement, guided by a citizen-centric perspective that prioritizes the needs of constituents.

- Embed change management. Collaborate at the front line with each agency to co-create solutions and gain buy-in on both the strategic objectives and the specific initiatives of the cost reduction campaign.

- Design for the future. Build foreseeable disruptions (such as demographic evolution, GenAI and other technologies, and climate adaptation) into the plan, ensuring that services are designed for the future and remain relevant and effective for meeting constituents’ evolving needs and demands.

Getting Started

Embarking on a journey towards smarter spending and improved services requires political will. But a few straightforward steps can start things moving.

- Clarify your strategic intent. Determine the primary reason for your cost-optimization campaign, such as reducing constituent burdens, or expanding services. Clear goals that benefit constituents and government agencies themselves will attract buy-in.

- Establish a cost baseline. Perform a thorough diagnostic analysis to pinpoint where the most significant cost-saving opportunities lie. Measure the starting point and analyze current spending patterns and calculate return-on-investment.

- Establish clear, measurable targets. Again, it’s hard to argue with metrics for success. Identify specific short- and long-term financial targets and performance objectives to guide your efforts.

- Form cross-functional teams. Bring together key stakeholders from affected departments to ensure a comprehensive approach.

With a prioritized set of objectives and targets, governments can quickly move to identify opportunities to optimize costs, enhance services, and achieve sustainable fiscal health.