Rapidly reducing methane levels in the atmosphere is one of the most effective ways to slow global warming. It’s small wonder, then, that pressure is growing on governments and companies to curb emissions of this potent greenhouse gas (GHG). In addition, by taking steps to abate their methane emissions early, companies can gain a significant competitive advantage.

Because their operations emit large volumes of methane, oil and gas companies have a major role to play in methane abatement. Although there are positive signs that leading players are taking action, the pace of change across the industry is too slow to limit the rise in global temperature to 1.5°C above preindustrial levels.

Oil and gas companies that fail to act with urgency and tackle their methane emissions could face a rough ride ahead. Changes to emissions-trading schemes, higher penalties, and greater scrutiny of methane emissions could leave industry laggards with far bigger financial liabilities—and potentially without access to markets.

Fortunately, methane abatement is among the most viable decarbonization levers available to oil and gas companies. Furthermore, abatement measures often make good business sense: in many cases, companies incur no net cost because the expense involved is less than the market value of the captured methane. BCG has identified six steps to help companies get started and accelerate their abatement journey.

The Shortfall in Methane Abatement

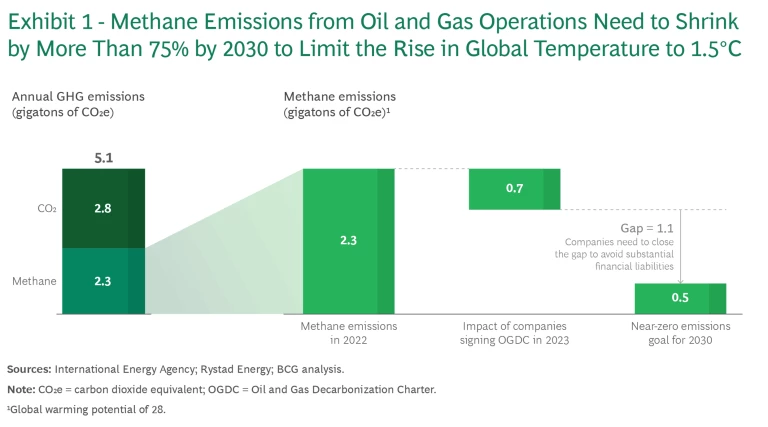

The global oil and gas industry generates about 5.1 gigatons of GHG emissions, measured in CO2 equivalent (CO2e) terms, from companies’ operations each year. Of this amount, about 45% is in the form of methane that is released into the atmosphere either as a result of leaks, venting, or incomplete combustion (for example, in flares and turbines).

A sharp reduction in GHG emissions is required if the world is to remain on the 1.5°C pathway set out in the Paris Agreement. (See Exhibit 1.) According to an International Energy Agency (IEA) report, Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, methane emissions from oil and gas operations must shrink by more than 75% by 2030 to avoid exceeding the Paris Agreement target.

Some leading companies are seizing the initiative and proactively cutting their methane emissions. At the COP28 meeting in December 2023, more than 50 oil and gas companies—representing more than 40% of global oil production and 30% of global gas production—signed the Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter (OGDC), a commitment to near-zero methane emissions (0.2% emissions intensity or less) by the end of the decade.

In addition, about 100 companies have agreed to report their methane emissions annually using the comprehensive measurement-based framework of the United Nations Environmental Programme: Oil and Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP) 2.0. Some companies are also participating in voluntary certification programs offered by third-party players that assess methane emissions across the supply chain on an asset-by-asset basis.

Fulfilling these commitments can have a material impact on methane emissions from oil and gas operations. But even after taking them into account, we estimate that there could be a gap—a difference of up to 1.1 gigatons of CO2e—between what oil and gas companies could be on track to deliver in emissions reductions by 2030 and what’s required according to the IEA’s net zero roadmap.

Why Companies Need to Act with Urgency

There are several reasons why companies should curb methane emissions quickly.

Governmental and Regulatory Actions. Governments worldwide are taking actions so that oil and gas companies reduce their emissions of methane and other GHGs. Legislatures are creating new reporting requirements and penalties, allocating public money to reduction efforts, and in some cases, adjusting cap-and-trade emissions schemes to make them more onerous. (See “Policy Developments Across the Globe.”)

Policy Developments Across the Globe

United States. In January 2024, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed a Waste Emissions Charge (WEC) for methane. The charge applies to petroleum and natural gas facilities emitting more than 25,000 metric tons of CO2 equivalent per year. Facilities whose 2024 methane emissions exceed certain thresholds incur a penalty of $900 per metric ton, which rises to $1,500 per metric ton in 2026.

As part of the government’s efforts to curb methane emissions from oil and gas operations, the EPA has introduced tougher reporting rules aimed at improving emissions transparency. Furthermore, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which was signed into law in November 2021, set aside $1.5 billion to support methane emissions abatement in oil and gas operations.

Europe. The European Union’s Fit-for-55 legislation (which aims to cut the bloc’s greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030) has imposed a variety of methane emissions-related requirements on the energy industry. Beginning in 2024, companies must measure, report, and verify their methane emissions. By 2027, they are banned from venting and flaring methane as part of their routine activities. Also, by 2027, new contracts importing oil, gas, and coal into the EU will be permitted only if the producers meet the same monitoring, reporting, and verification obligations as EU-based ones. Foreign producers will need to keep methane emissions below specified thresholds to avoid penalties and maintain their ability to export to the bloc.

In addition, the European Commission (EC) has taken steps to increase the speed at which it cuts greenhouse gas allowances granted to large emitters under its Emissions Trading System (ETS). Starting in 2021, the total number of allowances—or cap—was reduced by 2.2% each year to encourage companies’ emissions-reduction efforts (emitters can also purchase additional allowances, or credits, via the ETS to make up the difference between emissions covered by allowances and their actual emissions). In 2023, the EC implemented a steeper reduction of 4.3% per year from 2024 through 2027 and 4.4% beginning in 2028. Because fewer allowances are available, the price of allowances is likely to rise, increasing the cost for European oil and gas companies that continue to emit large amounts of methane. We estimate that EU ETS prices could double by 2040.

Australia. As part of a July 2023 reform of the Safeguard Mechanism, Australia’s policy for tackling large industrial emitters, the government introduced a new rule cutting greenhouse gas emissions allowances (or credits) given to these companies by 5% each year through 2030. BCG estimates that the change could result in the price of credits tripling by 2030, creating a potential liability of up to $1.2 billion per year for Australia’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry, a significant emitter of methane.

Japan and South Korea. In July 2023, the Korea Gas Corporation and Japan’s JERA, the world’s two largest LNG buyers, launched the Coalition for LNG Emissions Abatement towards Net-zero, a public-private initiative supported by the governments of Japan, South Korea, Australia, and the US, as well as the EC. The initiative aims to increase the visibility of methane emissions in the LNG supply chain and develop best practices for reducing them.

Companies will want to act for other reasons as well. Failure to curb methane emissions could jeopardize oil and gas players’ green businesses if their upstream operations are heavy methane emitters. Additionally, not controlling methane leaks could undermine the role of natural gas—which is largely made up of methane—as a transition fuel. In the worst-case scenario, failure to reduce methane emissions could result in regulators restricting companies’ access to markets. Beginning in 2027, for example, companies that export oil, gas, and coal to the European Union will be held to the same methane requirements as EU producers.

Greater Recognition of Methane’s Warming Potential. GHGs, such as methane, cause global temperatures to rise by trapping and absorbing heat energy in the atmosphere, slowing the pace at which this energy escapes into space. To understand the relative potency of individual gases, governments and international agencies use the Global Warming Potential (GWP) index. This measures how much energy the emissions of 1 ton of a given greenhouse gas can absorb over a certain time frame compared with the emissions of 1 ton of CO2. Methane’s global warming potential has increased 33% since 2015 as scientists’ understanding of the climate impact of the gas has improved.

Subscribe to our Energy E-Alert.

The GWP index typically measures gases over a 100-year time frame. On this basis, methane has a global warming potential of 28. However, methane has a far bigger initial impact on global warming than does CO2 because methane is broken down more quickly by natural processes . Using a 20-year time frame that takes this dynamic into account, methane’s global warming potential increases to 84.

As pressure grows to reflect methane’s impact in a more realistic and meaningful way, governments and agencies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change may have to alter their methodologies and adopt a 20-year perspective. The knock-on effects would include higher penalties and the requirement for uncovered emitters to purchase far more allowances, increasing their costs substantially.

Increased Scrutiny. Technologies and approaches for detecting, measuring, and attributing methane emissions occurrences have improved dramatically. Despite this, many companies still calculate their GHG emissions (rather than measure them) using emissions factors. This approach can result in emissions being significantly understated. However, new systems have recently been developed that can provide regulators with the empirical data needed to support actions against methane emitters.

Launched at COP28, the International Methane Emissions Observatory’s Methane Alert and Response System (MARS) is the first global system to transparently collect information about methane emissions occurrences via satellite and notify the responsible parties. From January 2023 through December 2023, MARS detected more than 1,000 energy sector-related methane plumes, linked 400 plumes to specific facilities, and informed six national governments and multiple OGMP 2.0 member companies of 127 events.

In March 2024, the Environmental Defense Fund, a US-based nonprofit organization, launched MethaneSAT. The satellite system identifies methane emissions events, attributes methane emissions to individual emitters, and tracks their progress in curbing emissions. The data MethaneSAT collects is publicly available and free of charge.

Given such advances in detection and measurement systems, companies should determine and address their true level of emissions.

Six Steps for Tackling Methane Emissions

The good news for oil and gas players that emit methane is that cost-effective methane abatement solutions are available. Indeed, according to the IEA, about 40% of emissions from oil and gas operations could be abated at no net cost (at the annual average price of natural gas from 2017 through 2021) because the investment expense of the abatement measures is less than the market value of the captured methane (which can be used to produce natural gas). The agency also estimates that it would require about $100 billion in investment from 2021 through 2030 to fully abate all methane emissions in the oil and gas sector—a fairly low sum when compared with the cost of other decarbonization initiatives.

Consider the cost of achieving near-zero methane emissions for an offshore platform emitting 4 kilotons of methane annually. In our experience, the required capex is about $10 million to $15 million, depending on the platform’s design, operating conditions, and the company’s procedures. This range compares with more than $150 million for an offshore power-from-shore electrification project and more than $250 million for an onshore postcombustion carbon capture and storage project.

We have identified six steps that oil and gas players can take to tackle methane emissions from their operations. It is important that companies start off on the right foot by following the first three steps. Then take the last three for a successful journey. (See Exhibit 2.)

Set the aspiration. There is nothing like a public commitment to mobilize the support of stakeholders, including employees, investors, and customers. So, don’t delay—make setting the company’s aspiration the first step. This aspiration can take several forms, such as better regulatory compliance or membership in OGMP 2.0 (which requires members to use the partnership’s comprehensive, measurement-based reporting framework). However, a commitment to near-zero methane emissions by 2030 is quickly emerging as the leading aspiration among industry players. Whatever the aspiration, it should align with the corporate strategy and local regulatory requirements. The aspiration also determines which industry and certification standards apply and the pace of abatement actions.

Find support for the journey. Developing and financing a methane emissions detection and measurement campaign and an abatement program requires upfront investment. In many cases, public-sector incentives can dramatically improve the business case for these initiatives. However, in jurisdictions that lack supportive policies, it can be a struggle for companies to fund and implement programs that can deliver meaningful methane emissions abatement.

Fortunately, some governments and companies are finding ways to help bring down the costs. For example, Canada has lent Colombia methane emissions detection and measurement equipment. And in the US, onshore oil and gas companies are jointly coordinating their abatement programs and sharing equipment.

In addition, several public- and private-sector funds are available for companies seeking to tackle their emissions. For example, the World Bank has launched the Global Flaring and Methane Reduction Partnership with the aim of helping governments and operators cut methane emissions from oil and gas operations. The partnership has a budget of more than $250 million and expects to secure additional funds from the private sector.

Develop a practical emissions baseline. Take a practical, agile approach toward developing an emissions baseline for future actions. Rapidly bring together the expertise to determine the company’s current methane emissions across technologies and suppliers, equipment, and asset classes. Start by selecting a pilot asset and create an inventory of all its equipment and processes that emit methane. Then design and conduct a detection and measurement exercise. We find that the majority of emissions come from a handful of source types, including pneumatic controllers, storage tanks, compressors, and valves. Fugitive emissions from pipelines can be a significant contributor, accounting for more than 80% of total operational emissions in some cases.

To develop the most effective detection and measurement process, companies should deploy a mix of site-level tools (such as satellites and drones) and source-level ones (such as handheld and fixed sensors). Using a third-party certification program can be helpful since such programs typically stipulate a required combination of measurement technologies.

Deploy a digital solution that can integrate data, actions, and reporting. Creating actionable insights out of complex emissions and operational data requires a robust, scalable digital solution that can integrate different data sets, actions, emissions standards, and reporting methods.

At a minimum, the solution needs to:

- Capture data in multiple data formats from a mix of detection technologies, internal IT systems, and operational systems

- Aggregate and contextualize what is measured in order to pinpoint sources of leaks

- Distinguish between actual leak events and operational events or false positives

- Trigger remedial action by field operators

- Feed data into reports

- Monitor progress against the company’s goal

- Calculate the value of the abatement program

Some technology providers have developed digital solutions that not only offer these features but also can identify the root cause of methane releases. By using companies’ operational data, these solutions can suggest both immediate repair actions and broader structural changes to operations.

In addition, some ambitious oil and gas players are designing solutions that enable third-party asset-level certification so that they can participate in voluntary carbon credit markets and sell near-zero methane emissions products.

Measure, track, and promote the company’s progress. Measure and track the company’s progress throughout the emissions-abatement journey. Regulations, reporting demands, and certification requirements can all impact what the company measures and tracks—and how. What’s more, they can make the process more complex. So, think about measuring and tracking your progress relatively early on.

At a minimum, measure and track activities so that the company can comply with the emissions reporting requirements that exist in its home region. In many regions, traditional bottom-up approaches that estimate emissions aren’t sufficiently rigorous to meet reporting requirements. Instead, many governments demand the direct measurement of emissions. As a result, using a digital solution that can reconcile measured emissions and operational data sets, and help ensure standardized reporting and transparency, is increasingly important. Furthermore, if the company sells near-zero methane emissions products, such as blue hydrogen, the company will also need third-party certification from a provider such as MiQ.

In addition to meeting reporting requirements, measure and track the company’s progress to garner internal support. Consider introducing posters and dashboards that promote awareness. Demonstrating progress against the company’s aspirational target can help maintain buy-in from external stakeholders.

Implement a company-wide transformation for sustainable near-zero emissions. To achieve sustained progress, adopt a structured approach to emissions abatement and establish an emissions control center. This center should oversee day-to-day leak tracking and repairs, reporting and certification, audit coordination and facilitation, and the creation of a knowledge database for training teams in the field. In addition to establishing a control center, companies should use all the data at their disposal from individual pieces of equipment and facilities to identify the operational changes that are needed to curb emissions and to make smart capital-allocation decisions.

Ultimately, however, a company-wide transformation is necessary—including establishing clear lines of accountability—in order for the organization to reach and maintain near-zero methane emissions. Start by getting employees excited about the abatement journey. Use initial projects to generate quick wins (by replacing wet with dry seals or high-bleed with low-bleed valves, for example), while also following a structured program that embeds methane emissions abatement goals across the organization. We find that four ingredients are necessary for long-term success: accountability, talent, workflows, and culture .

Oil and gas companies’ operations are among the largest emitters of methane. As pressure grows on governments to reduce GHGs and limit the rise in the global temperature to 1.5°C as set forth in the Paris Agreement, oil and gas companies are facing more and more regulatory actions and increased scrutiny. Some oil and gas companies are cutting their emissions. More should follow their lead. Given that companies can gain significant competitive advantage and that many cost-effective abatement tools and technologies are available, oil and gas companies should embark on their abatement journey today.