Geopolitical forces are making the world an increasingly volatile and disrupted place. The war in Ukraine, rising tensions between the US and China, and the conflict situation in the Middle East are just the most immediate and highest-profile examples of a world in which security and stability for business seem less achievable than they have for many decades.

As these trade frictions grow and trust in multilateralism weakens, the global market is becoming far more fragmented. The largely cooperative trade environment that enabled companies to build global supply chains in recent decades is rapidly being replaced by a more uncertain world, characterized by a mix of smaller regional and local supply chains.

This change is also taking place against a backdrop of low growth and productivity challenges. For example, in the fourth quarter of 2023, Eurozone growth was just 0.1%, whereas the US economy grew by 3.1% in the same

The effects on the EU are likely to be profound, and we must ensure leaders across governments and the private sector are prepared, with insight and clarity that can help them formulate a balanced approach to the coming uncertainties.

In his recent report More Than Just A Market, Enrico Letta reminds us that free trade and openness are key principles at the heart of the EU economic model. But, as he also points out, it is precisely because the EU has historically been so open that a world increasingly fragmented by geopolitics presents the region with new challenges in its global trading relationships.

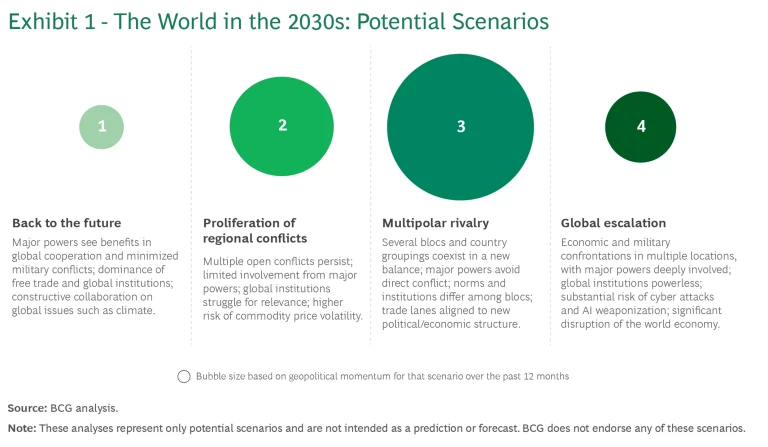

As we survey this complex landscape, BCG sees the following four possible “biggest-picture” scenarios for how the world might look in 2030:

- Back to the Future? Major powers will see benefits in cooperation and be keen to play down further military conflicts, leading to a focus on free trade with common rules successfully enforced through global institutions such as the World Trade Organization (WTO).

- Proliferation of Regional Conflicts. Multiple ongoing conflicts will persist, but major powers will limit their direct involvement in them. At the same time, the inability of global institutions to resolve these conflicts will lead to ongoing chronic uncertainty and downward pressure on global economic growth and investment.

- Multipolar Rivalry. A range of blocs will emerge with different institutions and norms, as well as new “middle powers.” Trade flows will adjust to reflect this more fragmented world.

- Global Escalation. Economic and military confrontations will grow more intense in multiple locations, with involvement from major powers. Global institutions will look increasingly powerless and be unable to act, leading to significant disruption to the global economy.

While all these outcomes are possible, current momentum is pointing toward the third scenario—a shift toward multipolar rivalry, in which the EU will be one of the key poles—by the end of the decade.

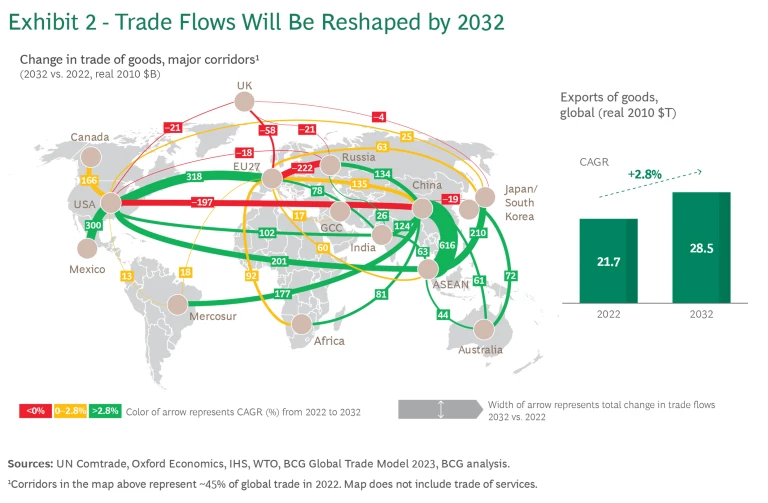

What will these changes mean for global trade? According to BCG’s Global Trade Model, which predicts goods trade flows ten years ahead, we expect to see trade growing worldwide at a slightly slower rate than the world economy. Global trade in goods is forecast to grow at 2.8% per year on average through 2032, compared with an estimated 3.1% growth rate for global GDP over the same period.

To stay competitive, European leaders will need to adapt to a world of multipolar rivalry.

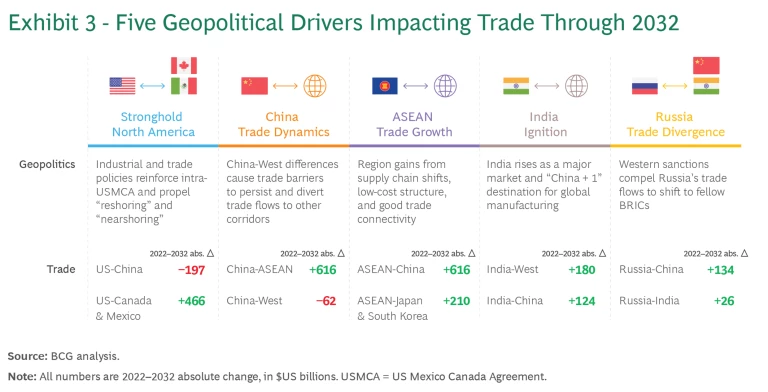

This global picture, however, hides marked differences between individual countries. Trade flows, and growth levels, will look very different in the world of 2032 compared with the past. We see the following five global geopolitical factors driving this:

- Stronghold North America

A consequence of the reduction in US-China trade will be greater trade between the US, Mexico, and Canada as partners in the USMCA trade agreement. Mexico will be the biggest winner here, with its trade with the US set to grow by $300 billion by 2032.2 - China’s Trade Dynamics

Trade tensions between China and the West, particularly the United States, will grow, leading to overall reductions in US-China trade. As far as the EU is concerned, Chinese trade will grow modestly, as the Union adopts a middle path, taking a tougher line on trade in strategic sectors while remaining more open elsewhere. - ASEAN Trade Growth

Equally impacted by the increased global focus on supply chain resilience is the ASEAN bloc. Countries such as Vietnam are an attractive alternative to companies adopting a “China + 1” strategy, leading to reconfiguration of trade flows via these locations. - India Ignition

India’s domestic market size, projected growth, and renewed emphasis on foreign direct investment make it a focus for economic development in the next decade. It is also another beneficiary of the China + 1 strategy, as major investments in sectors such as consumer electronics and semiconductors show. - Russia Trade Divergence

The break in Russia’s trade with the EU and the US caused by the war in Ukraine and the resulting sanctions has impacted the EU and Russian economies. While Russia will increasingly trade with other partners, its trade with the EU will continue to fall massively. We do not see a credible scenario in which sanctions on Russia are significantly eased in the short or medium term.

These are our global perspectives. But what are the implications when viewed from the EU perspective?

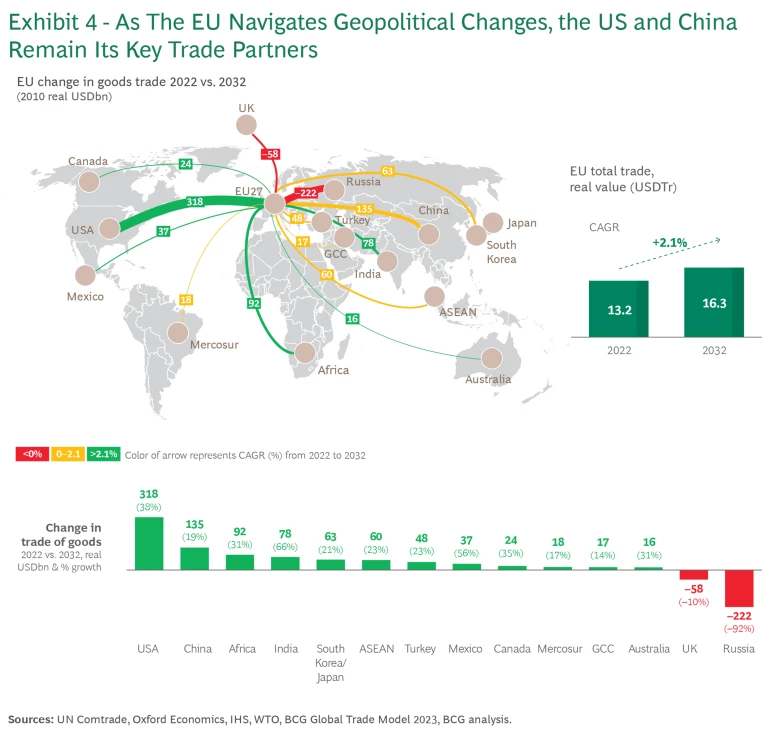

When looked at from the perspective of EU trade (both between the members of the bloc and with third countries) we see a similar picture. BCG’s analysis predicts that EU trade will grow more slowly than at the global level, at just 2.1% a year. And just as we saw globally, the EU’s trade in 2032 will look very different from how it did in 2022.

First and foremost, trade relations with Russia will not resume for the foreseeable future. The EU needs to continue to plan for a future without access to Russian gas or critical minerals, or to Russian consumers.

Second, the EU will become more dependent on other countries—notably, the US and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries—for energy imports. This brings with it new risks, such as the recent moratorium on new US LNG export terminals. A shift to decarbonizing industry will help, but doing so, in turn, creates new dependencies of their own—for example on critical minerals—which will need to be managed.

Third, the EU’s focus on values-based trade—through measures such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism—will increasingly impact trade flows. Imports of impacted products from countries that have higher carbon footprints and/or ESG challenges will see a decline. These measures also have the potential to disrupt trade flows further—for example, by impacting the EU’s export competitiveness in third-country markets and potentially provoking retaliation from affected trading partners.

Fourth, these broader geopolitical shifts mean that emerging markets will be key growth areas in the future economy. But the EU’s trade relationships with these markets are currently underdeveloped, so signing Free Trade Agreements with Mercosur and India, for example, will be of increasing importance.

And finally, China will remain an important trading partner, but with risks that need to be managed—for example, in its dominance of certain critical mineral value chains. Getting the balance right, protecting the EU’s strategic autonomy in key sectors while maintaining global trade openness, will be crucial.

Trade flows, and growth levels,will look very different in the world of 2032 compared with the past.

As the EU enters its new political cycle, business and government leaders need to be more aware than ever of the geopolitical forces influencing the global economy and the EU’s place within it.

The following are four key recommendations for leaders as they formulate future strategy:

- Improve understanding of geopolitical risk. Multiple developments are possible for the world economy and global trade. Leaders should build geopolitical muscle in decision-making and planning for a range of scenarios. In particular, geopolitical risk identification, analysis, and mitigation should be embedded into corporate strategic planning.

- Focus on resilience through diversification. As COVID and the Russia-Ukraine war have shown, EU supply chains have too many single points of failure. Understanding trade dynamics is a critical first step to improving supply chain security.

- Understand growth opportunities. The trade flows of 2032 will look very different from the trade flows of today. It is therefore important to develop strategies to take advantage of predicted growth in emerging markets such as ASEAN and India.

- Seize the opportunities from climate leadership. The EU’s commitment to a net zero economy unlocks significant new opportunities in green tech sectors from hydrogen to automotive. The next decade will be critical; leaders should stay ahead of the curve to secure advantage and maintain their carbon competitiveness in the green economy of the future.

The EU’s trade openness is a key strength, and one which it should continue to leverage as it seeks to boost economic growth. But an increasingly uncertain future requires new strategies to succeed. By acknowledging this new reality, the EU has an opportunity to secure its global influence and competitiveness—while also protecting its strategic autonomy.