If you’ve ever served on a leadership team, you’ve probably had the feeling that things weren’t always going quite the way they should. Hours sitting through meetings and half-listening as each person gives their update to the team leader, the same few people hogging the floor—and wondering “what are we all doing here?” Thinking everyone’s agreed to something and then weeks or months later reopening the issue. Lacking clarity about which activities are team priorities and which ones the team should hand off. Everyone protecting their own resources and pet projects. Feeling like your peers don’t have your back.

Sound familiar?

Even those leadership teams (LTs) that have tried to address these issues often end up frustrated. Typically, they travel to some attractive getaway, do some kind of immersive team-building activity, and spend a day talking about how they plan to team better together. They leave with a renewed sense of optimism—but a few weeks later, things go back to the way they were.

Why is it so hard for LTs to be effective? In large part, it’s because of the overwhelming complexity executives must navigate—tactically and strategically—every day. Operating in a globalized, fast-changing world presents challenges that were almost unthinkable a generation ago. LTs must not only guide their organization to perform—to deliver on quarterly earnings projections or organizational priorities—but in this era of “always-on” transformation, they also need to enable their organizations to transform. Leaders are constantly surveilling the landscape to understand an increasingly knotty set of stakeholder needs and quickly adapt to shifting trends and disruptions. In fact, the need to transform has become so pervasive that it can no longer be relegated to a one-off program or standalone project team.

Operating in a globalized, fast-changing world presents challenges that were almost unthinkable a generation ago.

Thus, to simultaneously elicit performance and steer transformation, team members must be fully aligned around the organization’s North Star. They need to work together to solve problems and to make the right decisions for the enterprise, sometimes at the expense of their individual agendas. They need to trust one another so that they can have candid conversations and make the right tradeoffs. They need to rely on each other to deliver, and they need to hold one another accountable.

That’s a tall order, and one that cannot be left to happenstance.

Our work over the years in guiding LTs has led us to three convictions about why they falter—and what they need to do to perform and transform in today’s relentlessly changing environment.

- Despite their good intentions, most LTs today are functioning as a group of “superheroes”—exceptionally talented high-performers whose focus and dedication to their own domain is what propelled them to the top ranks. But it’s no longer possible (if it ever was) for the hero CEO, or even a group of heroes, to grapple alone with the complexities of a constantly and exponentially changing world. Instead, they need to become a super team: one that can move quickly, in unison, anticipating where the ball will land rather than focusing on where it is today. They need to harness the full power of the team to deliver on the needs of the enterprise. And to do that, they need to shift to an enterprise-first mindset, which calls for a new set of beliefs, behaviors, and practices.

- Although they are operating in an environment of constant change, most LTs today still focus primarily on performing; they have not yet tangibly acknowledged the need to transform. Unlike teams whose purpose is to develop and deliver products and services, leadership teams exist to guide and inspire the work of those in their respective organizations. To enable their organizations to perform and transform, LTs need to change how they engage with each other and with the rest of the organization. And to do so effectively, they need to draw on a holistic set of attributes and behaviors we metaphorically refer to as the “Head, Heart, and Hands.”

- Most LTs today don’t dedicate the time and effort needed to carry out their dual mandate. To perform and transform, LTs need to be willing to undertake a sustained and at times uncomfortable process of engaging in self-reflection and defining and reinforcing a set of commitments—all of which require ongoing practice, both as individuals and collectively, as a team.

As those who have experienced being on a super team can attest, the effort required to get there can seem daunting. But the rewards—for the team as a whole, the individual members, and the broader organization— are significant. Here, we explore the principles and practices that have guided many leadership teams on their journey from a confederation of superheroes to a unified super leadership team.

From Many to One

Most individuals who make it onto a leadership team have shown considerable determination in creating a bold, value-creating plan for their own individual team, business, or function; in securing the necessary resources; and in executing the plan. Their service on the LT is in fact recognition and reward for adeptly deploying these “superpowers” to deliver results.

Their past success frequently meant protecting their resources at all costs, often putting their own team first—even, at times, at the expense of the enterprise. In fact, the culture at many organizations rewards individual “heroics”—leaders who step in to put out a fire or shepherd the company through a crisis. When these heroes get to the LT, they have to reframe their thinking: now it’s about staying energized around the organization’s collective purpose.

Adopting an enterprise-first mindset requires reframing every decision the leadership team faces.

Adopting an enterprise-first mindset requires reframing every decision the LT faces: Is this the right answer for the enterprise as a whole? Is it consistent with our organization’s purpose, strategy, and priorities? If what is best for the enterprise conflicts with what is best for an individual leader’s domain (or their own team members) it may mean reallocating resources or capital investment away from that leader’s group, pausing or sunsetting a pet project, or even eliminating job positions—which could affect the same individuals the leader has previously advocated for or protected.

For many leaders, joining a LT is often the first time that their “primary team” is not the team that they manage. It helps to appoint leaders who already have a track record of acting on behalf of the enterprise. Inculcating this mindset requires clarifying what “enterprise first” expectations look like and explicitly soliciting commitments from each team member. It often requires revisiting and aligning incentives to ensure that leaders are in fact rewarded for their enterprise orientation and results. Like any new behavior, it also requires ongoing practice and reinforcement from the team leader and other team members—calling out individual-oriented behavior and celebrating enterprise-oriented behavior.

A pharma CEO sums it up well: “When we onboard new LT members, one of the first things I make clear is that your first team is the executive team, not the functional team you lead. You are not here to defend your direct reports. You are here to do what’s right for our company and our stakeholders. The enterprise comes first, and your function is how we support the enterprise goals. Everyone understands this. If someone fails to operate in this way, their time on the executive LT is short-lived.”

The Head, Heart, and Hands of Effective Teaming

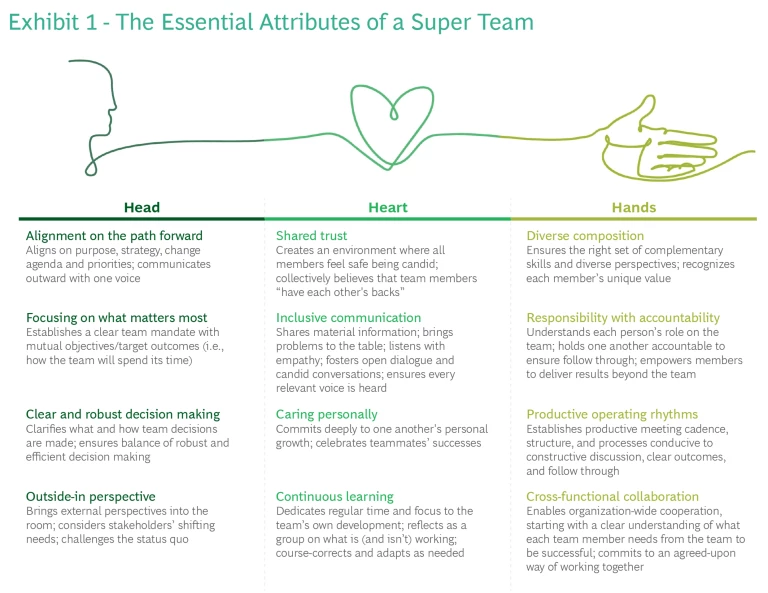

To deliver performance and drive transformation, LT members need to change how they engage with each other and with the rest of the organization. Through our experience with numerous leadership teams, we’ve distilled 12 key attributes that help them not only engage effectively within and beyond the team, but also achieve the ultimate purpose: high impact and increased value creation. We refer to these attributes collectively as the Head, Heart, and Hands. Think of them as what fuels the superpower of super teams:

- The Head refers to aligning on the path forward, committing to a common purpose with clear goals and priorities, carrying out clear and robust decision making, and seeking outside-in perspectives.

- The Heart encompasses fostering trust and inclusive communication and caring about one another and about one another’s success. (As one CEO says, “We believe that if one of us is not successful, we all fail.”) Another aspect of Heart: valuing continuous learning.

- The Hands involve ensuring diverse composition, clarity of responsibilities and accountabilities, and productive ways of working. It also includes emphasizing collaboration.

Getting the “Head” Right

The “Head” of the LT is fundamentally about envisioning the future and aligning the “big rocks”—the organization’s top priorities—with its purpose, goals, strategy, and

In the past few years, LTs have been grappling with heightened uncertainty and evolving risk—realities they must account for in their strategy, as one US-based C-suite executive notes. “You hope that your overall vision and high-level strategy will stay on course,” he says. “But what you need to do to achieve them changes dramatically. You need to be continuously reassessing what’s working and what isn’t and [redeploying your resources] accordingly. What's hard for a lot of leaders is that they want to know when the change is going to stop. But that’s never going to happen.”

LTs need to find a way to keep attuned to what’s happening both externally and internally, and they should have the right decision-making processes and norms in place that enable them to respond quickly. Leadership teams also need to think carefully about their role and mandate. They should ask:

- What should we be spending our time on as a team?

- What are the key operational metrics for which we are accountable?

- What are the two or three enterprise-level initiatives that affect everyone in the organization?

- What are the key issues or challenges we need to solve together?

- What messages do we need to communicate to the rest of the organization with one voice to ensure clarity and consistency?

Another critical question LTs need to consider is which decisions should remain in their purview and which ones should they delegate down. A common pitfall for LTs is getting caught up in operational minutiae, which drains precious time needed to tackle the important issues. Says a pharma CEO: “We are very clear on our role as as an executive LT: we set strategy and priorities. However, once we agree on a strategic move, we won’t micromanage it; whoever leads that function decides on the executional tactics. For example, we own portfolio decisions. But we don’t decide on things like promotions and discounts. You need to empower your team to make those decisions and trust them to do it.”

We agree wholeheartedly. If the LT were to own every decision, the next level of leadership would never have the autonomy to make timely decisions, nor would they develop the decision-making muscle needed to one day sit on the LT. To keep themselves honest, this CEO’s LT dedicates the last five minutes of every meeting to reflecting on which topics they discussed that should not have been escalated to their level.

One of an LT’s most critical jobs is allocating and reallocating resources as enterprise priorities change. Every member must choose what’s best for the enterprise, even if it’s at the expense of their own area’s agenda. As one US CEO says, “[In] today’s world, we must be much more flexible about the way we allocate resources. No money is ‘yours’; it is ‘ours.’ If an issue arises over here that needs addressing, or we have an opportunity over there and this opportunity is not as big as that opportunity, we move things around. Each of our executive LT members understands this.”

Getting to the “Heart” of the Matter

As we’ve discussed, LTs today “need to be comfortable with uncertainty…and prepared to respond,” in the words of one C-suite executive. This requires trust, understanding, and transparency. Each team member needs to feel supported by the others.

Our research shows that the Heart is the most overlooked and shortchanged of the three elements, although it has the greatest impact. Indeed, it acts as a force multiplier in creating a super team. Take trust, for example. Trust among LT members is arguably more important today than ever. Team members must be willing to share their concerns and admit their mistakes, to voice their opinions without fear of retribution, and to concede to tradeoffs that may not always be in their best interest. These attitudes and behaviors require not just empathy, but also selflessness.

But establishing trust can be hard, for practical reasons: many LTs’ members are geographically dispersed or work remotely. When people do not work side by side every day, trust takes longer to develop. And whenever there’s a significant change in team composition, relationships among members must be cultivated from scratch.

Trust among LT members is more important today than ever.

Trust also fosters inclusive communication. The pharma CEO offers an example of what can happen in its absence: “I take bad news, really, really well if I find out when you find out. But, if you've known for a while and you surprise me with it, that’s a big problem. You didn't trust me and your peers to help you deal with it. You didn't trust that collectively we could come up with a better answer. Our role as an executive LT is to help each other solve tough problems. We can’t do that if we don’t know about them.”

To be clear, inclusive communication is not the same as consensus-driven decision making. Rather, it refers to sharing material information, airing bad news, carrying out open dialogue, and listening with empathy. It means giving everyone the chance to challenge, debate, and express their point of view. Inclusive communication is particularly important for anticipating change and continuously transforming as an organization. Another CEO told us, “Having a diverse set of perspectives at the table can help you see weak signals or new risks coming that you might not have seen.” Each LT member must, in turn, listen to their own teams to discover “what they are hearing and seeing out in the market, and bring this information to the LT. [To get it right], we need every diverse voice to speak up and to be heard.”

Listening is a critical skill. On his team, says this CEO, members expect each other to “spend most of their time seeking to understand rather than taking a position.” In fact, he says, “We have a shared language for this through our team norms.” If somebody is lobbying for a particular position, “We can say, ‘I hear you advocating strongly. I know how you feel, but can we stay in understanding mode for a little while longer? Because it seems we’re not all on the same page yet.’” Once a decision has been made, members can get behind that decision. This CEO’s example brings to mind one of Amazon’s leadership principles: “Have a backbone. Disagree. Commit.”

Members of super teams care personally about one another. They do not always agree, nor should they. They value the success of the team—and of the organization—as much, or more, than their own. They take the time to get to know one another and to understand each other’s stories, experiences, values, and dreams. They ask for and offer feedback and are invested in each other’s learning, development, and growth as well as the team’s as a whole. Interestingly, we’ve found that sharing personal experiences is often where the greatest progress in building camaraderie occurs. (See “Getting to Know You.”)

Getting to Know You

As a starting point for any LT effectiveness effort, try dedicating two or three hours to a simple exercise. Ask each team member to spend five to ten minutes sharing an experience or influence that has shaped them. Ask them how this serves them as a leader—and how it gets in the way. Then, allow each team member to ask questions. Let them reflect on how these stories link to or explain the way they experience this leader.

Initially, this exercise is often met with resistance or eye-rolling. But it is a monumental “unlock” for the team. By the end of the program, people often tout it as the most valuable time spent. It’s not unusual to hear comments like, “I’ve been working with Rob for 20 years, and now I finally understand him.” Conducting this type of exercise up front sets the tone for open, productive dialogue—not only while the team is deep in the work of building its effectiveness, but also for the duration of the team’s time together.

Finally, it's worth noting that, like the chambers of the human heart, the elements of the LT heart work together. Trust, for example, enables transparency; listening demonstrates caring; and caring, in turn, bolsters trust.

Leadership teams are, in essence, the heart of the organization. They pump blood into the rest of the enterprise by enabling, empowering, and inspiring. An LT whose members treat one another with heart is able to do the same for its employees, its customers, and its other stakeholders.

Putting the “Hands” into Action

Once aligned on the future direction and the priorities needed for the organization to perform and transform—and once they take to heart the importance of trust, communication, caring, and learning—LT members need to focus on execution.

It’s the LT’s job to translate enterprise-level goals and priorities into an execution roadmap for the rest of the organization. The LT needs to assign roles and responsibilities among its members and their respective functions and lines of business. Members need to understand their shared responsibilities: What are they on the hook for delivering together, and what are their respective roles in making it happen?

LT members must then hold each other accountable for following through. Gone are the days of “hub and spoke” accountability, where each team member answers only to the CEO. Given the complexity of business today and the speed with which organizations need to operate, it’s incumbent on LT members to actively support and count on each other.

At one financial services company we work with, the CEO describes how his executive leadership team successfully shifted from a culture of finger-pointing to one in which there was no longer such a thing as “your problem.” Issues that arise are now “our problem.” Says the CEO, “Team members used to expect me to resolve their disagreements. I told them, ‘If you come to me asking me to break the tie, I will automatically decide against you.’” That did the trick. “Members work it out. They proactively reach out to one another and feel collectively accountable.”

In adopting a collaborative working style, the LT serves as a role model for the rest of the organization. Members should regularly ask one another, “What interdependencies between our two functions do we need to manage? What do you need from me and my area in order fulfill your priorities?” And most importantly, “How can each of us help?”

In adopting a collaborative working style, the LT serves as a role model for the rest of the organization.

One North American CEO reflects on her company’s first leadership meeting for its top 500 leaders after the COVID-19 lockdowns ended, when travel and in-person meetings resumed. She told her executive LT, “If we're going to meet the challenges of all this uncertainty we face as an organization, we need more of our people collaborating. Our leaders need to see firsthand how we collaborate as a leadership team…as enterprise leaders. If they don’t experience the trust and the friendship [we share], this whole meeting will be a failure.” As it turned out, she notes, “The number-one feedback we got from participants was that they couldn't believe how well we got along as a team. They left thinking about how to carry this into their own teams.”

Finally, LTs need to establish appropriate operating rhythms and processes that support collaboration and effective execution. They need to create and commit to a set of team behavioral norms and decision-making processes and practices—including meeting cadence, agendas, and procedures. By consciously choosing these, they can ensure productive discussion with a bias toward action and follow-through.

Becoming a Super Team: Reflecting, Committing, Practicing

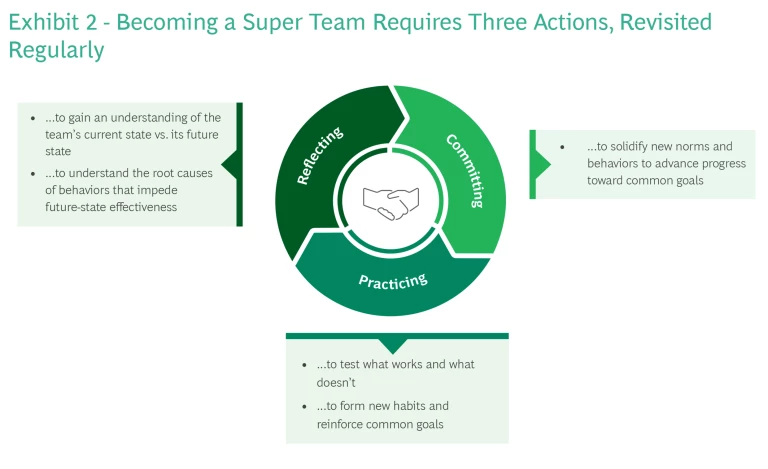

Most LTs have a fairly good sense of what’s working and not working. Where they get stuck is in bridging the gap between awareness and action—between knowing and doing. The Head, Heart, and Hands attributes provide teams with a clear picture of what “good” looks like—what makes a super team. To bridge that gap, teams need to follow an intentional and repeatable process: reflecting, committing, and practicing new behaviors and ways of working, both together as a team and as individuals. (See Exhibit 2.)

Reflecting

Many teams feel pressured to “just get on with it.” But leaders must be realistic. A three-hour workshop or even a three-day offsite will not magically turn a LT into a super team. The work of an LT is enormously consequential; getting on with it without consciously understanding the team’s dynamics as well as each individual’s motivations and ways of thinking, solving problems, and making decisions—and without adopting the new mindset and behaviors—will only subvert the team’s chances of success.

Being intentional is crucial, and taking time up front for reflection is a vital first step. Members need to think deeply about the beliefs, values, and behaviors that are helping—or hindering—them in their effort to become a super team. They need to understand what works and what doesn’t and identify the root causes underpinning their lack of progress.

Reflection involves identifying the strengths and opportunities as a team. LTs should ask themselves, “What is our current dynamic? Where are we today, and where do we want to be?” Relative to the Head, Heart, and Hands attributes, they should ask, “What do we do well? Where do we fall short?” And given the direction they’ve set as an organization, “Which attributes are most critical for our success?”

Leadership teams should ask themselves, “What is our current dynamic? Where are we today, and where do we want to be?’

Once identifying these gaps, teams need to delve into the root causes and decide how to address them. “What’s driving our subpar behavior in specific areas? What ‘elephants’ in the room haven’t we addressed? Are there things we do as a team just because ‘it’s how we’ve always done it?’” A team, for example, may see it needs to work on collaboration and transparency. Upon further reflection, though, it may discover what’s standing in the way: the fear of sharing information, triggered by a longstanding culture of “every man for himself.”

On the individual level, team members need to look within themselves to reflect on their individual beliefs, motivators, and behaviors and how they all contribute to team dynamics. They must ask themselves, “How am I ‘showing up’ for the team? In what ways might I be derailing the conversation or hindering our progress? What assumptions or fears am I holding that may be causing me to act in this way? Which of my prior experiences could be a factor?”

Across organizations, we find a consistent bias in individuals when assessing team effectiveness. It’s a natural tendency to attribute blame elsewhere. People give their own behavior the highest rating; the team’s, an average rating; and their other team members the worst. The issue is never “me,” it’s almost always “them.”

LT members should also take the time to reflect on the unique values and contributions that each of their peers brings to the table. This goes beyond functional and technical expertise. For example, who naturally plays the role of optimist? Who pressure-tests and challenges? Who is the “big thinker”? Who translates those big thoughts into practical next steps? By actively reflecting on each person’s unique value and contributions, the LT can leverage these individual superpowers to become a super team.

Committing

After reflection comes the deep work of committing to the team’s purpose, mandate, priorities, areas for growth, and manner of operating. This stage is the foundation for action as a super team. Here, members ask: “What are we uniquely qualified to tackle together? What kinds of issues and topics should we focus on—and what is best left to other organizational leaders to deal with? What is the best use of our time? How will we agree to work together to maximize our productivity and help us achieve clear outcomes, and what working rhythms, meeting formats, and operational processes should we follow?”

Every team should establish a set of team norms—a “contract” that stipulates how they will behave and work together and enable organization-wide collaboration. For instance, everyone should understand each person’s role on the team, taking them to task on their responsibilities and empowering them beyond the team to deliver results. Once there is clarity on roles, team norms govern the target mindsets and behaviors that members will commit to collectively and individually—and how they will hold each other accountable for living them.

Importantly, as LT’s shape their norms, they also need to define and commit to what they will stop doing—including unproductive behaviors that have historically gotten in their way. And they should prescribe the ways in which they will hold each other accountable for stopping these behaviors and calling each other out when they surface. (See “Sample Leadership Team Norms.”)

Sample Leadership Team Norms

Aligning as One

- Think at the enterprise level and optimize for the good of the company.

- Make decisions that drive value for our customers, our people, our shareholders.

- Stop the things that are not aligned to our North Star.

- Communicate with “one voice.”

Communicating with Care

- Choose trust.

- Ask for help, offer help: turn “your problem” into “our problem” to solve together.

- Seek to understand, listen, and learn.

- Speak your mind in the room: “Say it or surrender it.”

- Lean into difficult conversation: challenge the issue, not the individual raising it.

Committing Toward Action

- Hold each other accountable for delivering on our commitments and living out our norms.

- Make decisions, lock arms, and commit; no reopening the issue.

- Recap, get specific about next steps and timelines.

To sustain these new commitments, it’s important to consider how the organizational context surrounding the LT drives leadership behaviors enterprise-wide. Whether it’s governance, performance-management systems, organizational structure, or technology constraints, these mechanisms hardwire our actions. Many teams overlook their existing incentive structure when beginning to commit to new ways of working. They need to ask themselves, “Does our current incentive structure promote the desired mindset and behaviors?” More often than not, it doesn’t.

To reinforce a team-focused mindset, some companies recalibrate their leadership compensation formulas, flipping the performance ratio between unit and enterprise from, say, 70:30 to 30:70. Pulling contextual levers in the organization not only increases the likelihood of real and sustained change; it also demonstrates the LT’s true commitment to the rest of the organization. People see the LT putting its money where its mouth is.

Individual team members, like the team as a whole, need to consider their roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities in meeting team commitments. Each person should ask themselves, “How will I commit to showing up differently? How will I accept feedback? How will I experiment, learn, and adjust? And how will I role-model our team behaviors and ways of working?”

Practicing

This stage is where team members take everything they’ve reflected on and committed to and put it to work. It is also where the real work begins. Practice means not only embedding new habits and ways of working; it also means unlearning old habits.

Here, teams experiment with new ways of working together and engaging. This is where the team norms come to life. One CEO recounted two ways she does this for her senior LTs:

- “Everyone should be able to represent anyone who can’t show up at a meeting. In other words, even if it’s not your opinion, I expect you to be able to raise the perspective of somebody else on the team. You need to know what it is, and voice it even if it conflicts with your view. Our executive LT models this all the time.”

- “We, as a team, have agreed that for bigger decisions we need to work that last 10% of that conversation to make sure we are pressure-testing from all angles. Everyone has permission to ‘ask for the last ten,’ as we say, and raise any remaining questions or concerns so we get it right.”

Super teams create accountability mechanisms to sustain the changes. A common example is beginning and ending meetings by reflecting on how well members have adhered to the team’s agreed-to norms. With the trust they’ve cultivated, they give each other feedback on how they are showing up as individual team members: how they are contributing, when and how they are derailing the conversation, and where and how they are living up to (or falling short of) their commitments. One team we know uses the “red card, yellow card” system that soccer referees use to declare penalties, a lighthearted way for members to call out someone who isn’t adhering to the norms.

Reflecting, committing, and practicing is an intentional and repeatable process. Teams must reflect on how they are practicing what they’ve committed to—and make adjustments along the way.

Transforming a group of individual leaders into an aligned, synergistic, high-performing, transformative team requires a significant time investment as well as a commitment. We’ve found that creating a super leadership team generally takes months, if not longer. It’s therefore vital to adjust expectations. Moreover, the LTs that we work with—even the super teams—understand that LT effectiveness is a work in progress. There is no finish line to becoming a super team. It’s not a destination or a static ideal, but rather an aspiration—an ongoing evolution.

In an environment of rapid change, increased complexity, and heightened interdependency—as new challenges arise or new team members join—LTs need to revisit and hone their practices over time. Being intentional about how they work together should be an ongoing effort. Teams must routinely reflect, commit, and practice their targeted mindsets and behaviors. They must continue to refine, challenge, and push one another to be better, engaging with the Head, Heart, and Hands ideals to become a super team that performs and transforms. Fortunately, as a work in progress, it doesn’t so much matter where you start but that you start.

Consider the observations of a board member of a major regional bank, made a year after the bank’s senior LT had begun its journey: “This is a different executive team from the one we saw just a year ago. We see complete unity of purpose, mutual accountability, and real excitement about the mission. They view one another as trustworthy, supportive partners. There is no more finger pointing, even when issues are brought up that are clearly in one person's shop. Members have each other’s backs.”

It hardly seems coincidental that in 2023, a trying year for regional banks, this bank had one of its most profitable years ever. Or that it made Fortune’s 2024 list of the World’s Most Admired Companies.

Make no mistake: turning superheroes into a super leadership team is hard work. But the payoff, to those who accomplish it, is well worth the effort.