On March 6, 2024, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) approved a major rule that, if it takes effect, would change how companies report the climate-related risks that they face.

The Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors rule, as its name suggests, aims to have companies that are listed on US stock exchanges disclose climate-related information that may materially affect their business and, in turn, investors’ decisions. Such disclosures would be akin to what investors receive from companies in Europe and other global markets.

For a coastal real estate company, for example, disclosures may include the risks posed to its properties by rising sea levels and tropical storms. For an agricultural company in a region at risk of severe droughts from climate change , disclosures may include the potential impact on crop yields, production costs, and ultimately, financial performance.

Although the rule is significantly less stringent than originally proposed, it is nevertheless controversial and has been the subject of litigation from state officials and from business and environmental groups alike. Given the uncertainty, the SEC issued a stay order until the litigation is complete.

Still, forward-thinking companies will want to understand the rule and take it into consideration when assessing business scenarios, drafting strategies, and setting priorities.

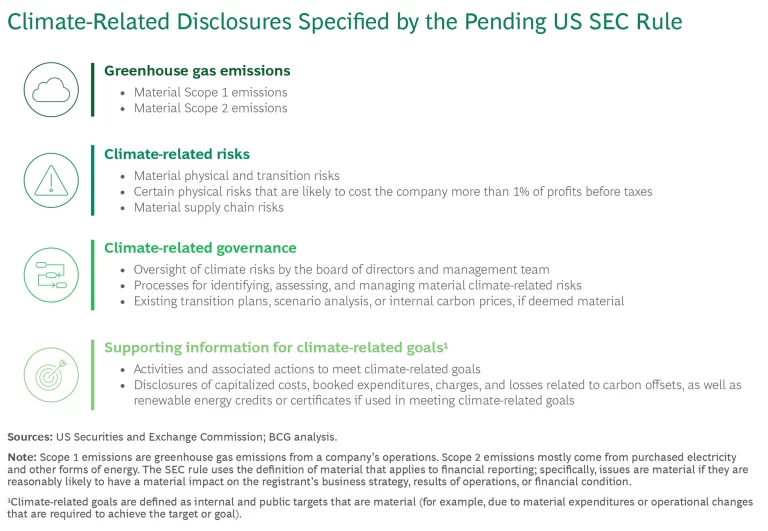

Four Main Disclosure Categories

The intent of the pending disclosure rule is to have publicly traded companies report a wide variety of material climate-related information. (See the exhibit.) The SEC rule uses the definition of material that applies to financial reporting. Specifically, information is material if it is “reasonably likely to have a material impact on the registrant’s business strategy, results of operations, or financial condition.” Four disclosure categories are important.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions. GHG emissions are a foremost climate concern, and the rule calls for companies to disclose Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions that are financially material in their quarterly and annual financial results (SEC forms 10-Q and 10-K, respectively). Scope 1 (or direct) emissions are from company operations, and Scope 2 (or indirect) emissions are mostly from the energy a company purchases and uses.

Climate-Related Risks. The rule also calls for companies to disclose material climate-related risks: physical risks, transition risks (those that come with adapting to climate regulations and standards), and supply chain risks. In the latter case, the SEC aims to have companies assess the risks in their supply chain without conducting expensive and time-consuming measurements of these so-called Scope 3 emissions.

For certain climate-related risks, the SEC enhanced the definition of materiality to include specific physical risks—such as severe weather events and other natural occurrences—that have or are likely to cost companies more than 1% of their pretax profits. This information would be included in companies’ financial statements, and companies would detail the capitalized costs incurred, expenses, charges, and losses from such events.

Climate-Related Governance. The SEC rule focuses on how companies are managing climate-related issues and their strategies and goals for addressing climate change. Specifically, it intends for companies to disclose how their board of directors and management team assess and handle climate-related risks, the processes used to identify and manage significant ones, and the actions—such as transition plans, scenario analyses, or internal carbon pricing—taken to reduce or adapt to such risks.

Supporting Information for Climate-Related Goals. The SEC rule also aims to gather information about companies’ climate goals that have materially impacted their business, operating results, or financial condition, or are likely to do so. This information would include the activities a company plans to undertake to achieve their goals and the timeline for achieving them. Companies would also disclose the capitalized costs, expenses, and any losses related to carbon offsets and renewable energy credits.

Nuances of the SEC Rule

It’s worthwhile to look at several other aspects of the pending climate disclosure rule.

Safe Harbor Protections. The SEC rule states that certain climate-related disclosures may involve estimates and assumptions based on future events and are therefore considered forward-looking statements. This means that such statements would be protected under the safe harbor provisions of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act, which shields companies from liability if certain forward-looking statements turn out to be incorrect. While the safe harbor provisions would cover climate-related disclosures about a company’s goals, transition plans, scenario analyses, and internal carbon pricing, the provisions wouldn’t apply to disclosures about a company’s Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions.

Equivalency with Other Climate Disclosure Requirements. The SEC did not specify how the climate disclosure rule would work with similar regulations adopted by other jurisdictions, such as the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and California’s climate-related laws. Such regulations require companies to disclose climate and sustainability risks. But the SEC did not clarify how companies subject to these and other laws can use one set of disclosure requirements to comply with its own rule. While the climate-related disclosures are similar, US companies may find that the costs are incremental when filing reports in multiple jurisdictions with similar requirements.

Materiality Considerations. The rule’s focus on gathering a wide variety of material climate-related information indicates that some disclosures, such as those about a company’s internal carbon pricing, would be quantitative. Others, such as the roles of the board of directors and management in addressing climate risks, would be qualitative, or descriptive.

When deciding what is material, companies would also consider the timeline and whether material risks are likely to happen soon—say, within the next 12 months—or further out.

Companies can show that they meet the reasonable investor standard by providing the parameters used to determine what is material.

By providing the parameters and facts—or as many as possible—used in determining what is material, both qualitatively and quantitatively, companies can show that they meet the reasonable investor standard.

The SEC’s climate-related disclosure rule is very similar to the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) framework, but it is not identical. The SEC rule covers the same ground as TCFD: governance,

risk management

, strategy, and metrics. It also uses similar definitions as the TCFD model and the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, given that they are widely recognized frameworks. However, the SEC rule does not follow every TCFD recommendation for determining materiality, so prudent investors will want to familiarize themselves with the SEC rule.

Planning Considerations

When drafting business strategies and setting priorities, proactive companies will consider addressing the following challenges whether or not the SEC rule takes effect.

New Processes and Capabilities. Companies that are new to filing climate-related disclosures often face challenges in several areas. These include:

- Identifying climate-related risks

- Creating governance procedures

- Capturing emissions data

- Developing practices that determine what information is material

At the outset, organizations also typically have challenges gathering the supporting information in each area.

Companies that already report climate-related information may be able to use their existing processes as a starting point, but if the SEC rule goes into effect, they’ll want to consider developing new strategies and controls for managing climate-related disclosures if they do not meet the standards used for financial reporting.

For many companies, the SEC rule could mean significant changes across departments. For example: collaboration among functions; investments in software and tools; adding roles, such as an environmental, social, and governance controller; and implementing new management systems to create quarterly and annual climate-related reviews. Such changes aim to ensure that a company can track, analyze, and report its climate-related information.

A National or Global Compliance Strategy. Companies often face challenges because there are multiple climate-related disclosure regulations in multiple jurisdictions that are pending, taking effect, or being considered.

For example, California has enacted three laws that mandate climate-related reporting by companies based in California and those doing business in the state. And the European Union’s CSRD will require disclosure from more than 3,000 US-based companies that operate in the EU.

Companies can expect the various regulations to have similarities and differences. For instance, the SEC’s climate disclosure rule would not require companies to disclose GHG emissions from their value chain (Scope 3 emissions). But regulations in other jurisdictions, including those in California and the EU, do require disclosure of these emissions—and New York and Illinois are two states considering Scope 3 rules of their own. In addition, one of California’s laws applies to companies with more than $1 billion in annual revenues, while another applies to companies with more than $500 million in annual revenues.

Moreover, various jurisdictions differ in their definition of a material disclosure. For example, Europe and China use a double materiality principle. This means that companies must disclose material information using two factors: how it affects their finances and how it impacts the environment and stakeholders outside the company.

A System for Assessing and Tracking Requirements. The jurisdictional differences in climate-related disclosures pose hurdles for assessing which requirements apply to the company and determining how to blend them into the management systems. And the dynamic state of the regulations challenges companies to track changes to the requirements.

The dynamic state of the regulations challenges companies to track changes to the requirements.

For example, the EU has created its own sustainability disclosure standards that must be used by companies that are subject to CSRD. Other countries, such as Japan, the UK, and Australia, are enacting policies that require companies to adhere to the standards of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). Notably, the SEC rule doesn’t reference any external disclosure standards, opting, instead, to outline its own disclosure standards in the rule.

Five No-Regrets Moves

Even with the ongoing litigation of the SEC rule and changing regulations in other jurisdictions, forward-thinking companies are asking themselves if they could comply with climate-related regulations if they were required to do so. These companies are raising the question because they realize that setting up new systems, processes, and tools, as well as building the necessary capabilities, take time.

Regardless of any one regulation’s specific requirements, companies can make five moves now to build the necessary capabilities.

Assess the company’s capabilities. Companies should first examine their current reporting practices and perform a gap analysis. This assessment analyzes their current disclosures, controls, and management systems to identify gaps with the SEC rule and other applicable regulations.

Companies should also review the timeline for complying with climate and sustainability disclosure requirements. Creating a schedule can help prioritize the actions needed to close any gaps.

Next, companies should test their systems, allowing enough time to make needed improvements and fix any deficiencies before any compliance deadlines.

Finally, companies should benchmark their system against those of their peers and industry leaders. Collaborating with other companies (without violating antitrust laws) can help identify and adopt best practices for climate-related disclosures.

Establish better cross-function coordination. Even for companies that have been reporting climate information for years, new rules can require greater collaboration among corporate functions. While the finance department typically handles financial reporting, climate disclosures are often the domain of a different function, such as the sustainability team. Companies should identify and define the roles in every department that are needed to comply with new requirements. The responsible, accountable, consulted, or informed (RACI) matrix—a common tool—can help define roles and responsibilities for each task.

Upgrade data tools. Determining a company’s climate impact is fundamentally a data issue. Since most companies can’t measure their GHG emissions directly, they provide estimates by using accounting rules and emission factors applied to their transactions data. Companies should assess the effectiveness of their current climate measurement methods and address any significant shortcomings before a compliance deadline. Key questions to ask include:

- Does the company’s tool set have planning, data analysis, and risk assessment tools?

- How easily can the measurement tools be integrated into the company’s IT systems?

- Do the tools need to be customized?

- Does integrating or using the tools pose any security concerns?

With the recent introduction of AI tools into corporate IT environments, companies should explore how AI technologies can make the climate disclosure process more efficient and effective.

Create a corporate-wide compliance strategy. Companies need to stay updated on changes in climate and sustainability disclosure standards and create a plan to comply with them. The requirements for each company depend on its business model, global footprint, supply chain, and plans for future products. It’s important to regularly review how the requirements change and to devise and maintain a strategy for how the company will comply.

Some companies may take a global approach, comparing all the applicable requirements and developing one system to comply with them all. Others may handle each jurisdiction separately. There can be cost savings in coordinating approaches and sharing resources, such as software tools, across the company.

Integrate climate risk into the corporate strategy. Corporate leadership teams and their board of directors should be able to identify and manage climate risks. To do so, companies should determine which current management systems can be adapted and where new systems are needed. This process includes:

- Evaluating the capabilities of each system at every level

- Assigning responsibilities and accountability to each system

- Creating a structured schedule of reviews and approvals that aligns with compliance deadlines

- Conducting an internal audit to validate the effectiveness of the implemented systems

It’s critical for companies to build, or reinforce, capabilities to assess the impact of climate risks—and quantify their exposure. Companies can then disclose material climate-related risks—and show how these risks may affect their strategy, business model, and outlook. Companies can also report the steps they’re taking to mitigate these risks, any relevant spending, and the impact of these activities.

Integrating climate risks into the corporate strategy and capital allocation process is paramount. As companies identify material risks, they should address them in their planning processes. This allows climate considerations to be weighed against other business priorities.

Even companies experienced in climate reporting will need time and resources to adapt to the pending SEC rule should it take effect. Despite the uncertainty, proactive companies will want to take steps to understand the rule and consider improving their capabilities to comply with the climate-related disclosure requirements.

This article should not be viewed as legal advice nor should it be used when filing SEC reports.