Many companies have increased shareholder returns by carving out noncore businesses and selling them to private equity firms or corporate buyers. But converting an integrated asset to a standalone entity is often costly, complex, and time-consuming , and it involves risk for both buyer and seller.

To maximize valuations and facilitate swift and smooth transactions, some experienced sellers separate the operations of a noncore business before offering it for sale. This “prepackaging” of the carved-out business could involve separating or otherwise preparing support functions, IT infrastructure and applications, or company accounting.

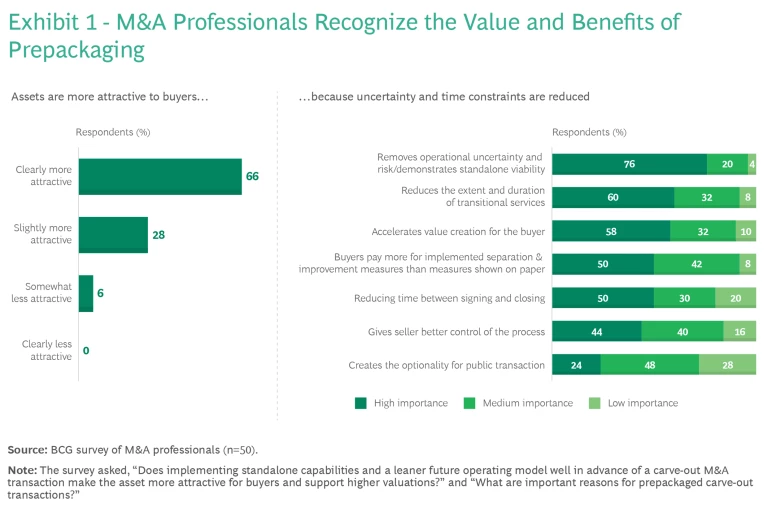

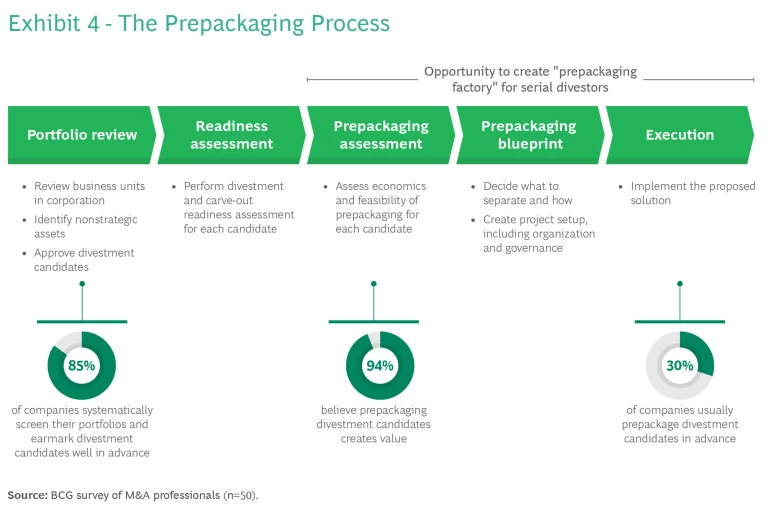

In a recent BCG survey of 50 M&A professionals, nearly all (94%) said that carving out standalone capabilities well in advance of a sale makes an asset more attractive and supports higher valuations. (See Exhibit 1.) Additionally, 85% of these professionals reported that their companies regularly screen their portfolios, providing a good line of sight on upcoming divestments. Yet only 30% said that they regularly prepackage their divestments. We see a clear opportunity for companies to create value by addressing this gap.

Prepackaging does, however, entail a variety of pros and cons that companies need to evaluate in each case. For example, while prepackaging often expands the pool of bidders by decreasing risks, it might deter sophisticated buyers who prefer to retain their options for how to set up the standalone entity.

To make an informed decision and capture the significant value at stake, companies should make consideration of whether and what to prepackage an essential step in every

divestiture

process.

What Is Prepackaging a Carve-out?

Prepackaging a carve-out refers to operationally separating a noncore business in anticipation of a divestiture. A significant portion of the separation is completed before the intention to divest is communicated to the market or the information memorandum is released.

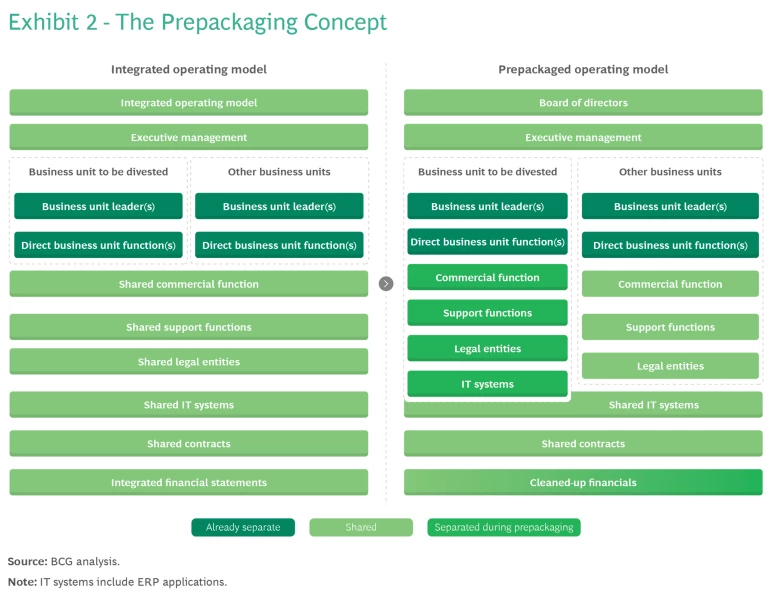

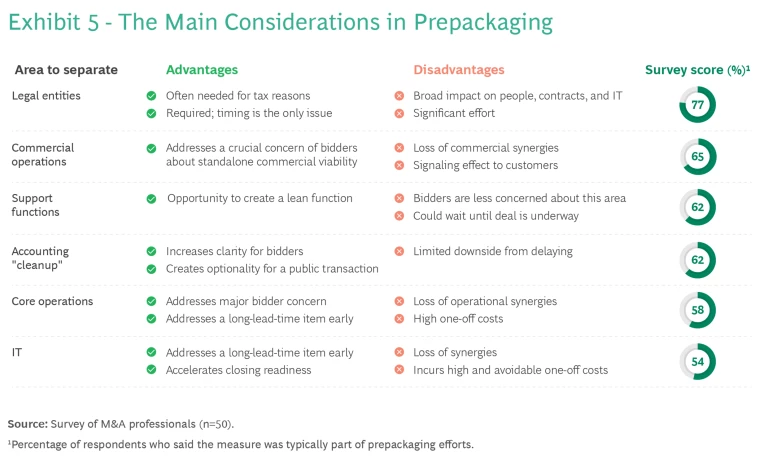

The M&A professionals we surveyed indicated that the most common target areas for pretransaction separation are legal entities, commercial operations, and support functions. However, as shown in Exhibit 2, the operational separation in a prepackaged carve-out is potentially broader, involving some or all of the following:

- Commercial functions, such as a common sales force and shared account management and marketing teams, are separated.

- Support functions, such as HR and finance, may be separated, streamlined, and run separately in-house, or they may be outsourced and optimized. As part of the process, they are tailored to the divested company’s business needs.

- ERP and IT applications are separated and their development and maintenance typically outsourced to a large degree. Existing shared IT could be replaced with more efficient and leaner core IT systems and processes tailored to the business’s specific needs.

- IT infrastructure is partially reconfigured. Separate technical platforms and cloud hosting arrangements are established if corresponding applications are already separate. Networks remain integrated but are designed to facilitate separability.

- Company financials are cleaned up, for example, by establishing separate cost centers and an independent P&L statement. This facilitates the rapid development of carve-out financials once the transaction process is launched.

- Legal entity structure is adjusted by moving the business into its own legal entities if it currently shares some entities with the parent company.

What Are the Economics of Prepackaging?

Companies that systematically review their business portfolios and reallocate capital to focus on core strengths generally outperform their less active peers by unlocking trapped value. BCG’s research shows that selling noncore businesses tends to yield higher value in terms of two-year relative TSR than selling core assets, and divestments to PE buyers yield higher value than those to non-PE buyers. The challenge for sellers is to maximize the value of such divestments.

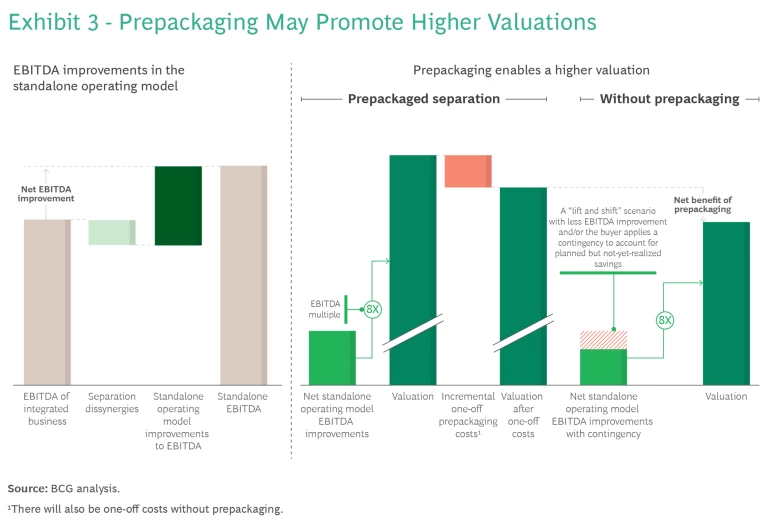

Demonstrating the future optimized EBITDA is perhaps the most powerful positive influence on asset valuation. (See Exhibit 3.) Companies that choose to prepackage have time to envision an optimized future operating model for the business, create an enhanced business plan, and actually implement and demonstrate EBITDA improvements.

In contrast, companies that separate the business during the deal have less time for planning. In many cases, the standalone operating model is, at best, envisioned but not implemented. This often forces sellers to resort to a “lift and shift” approach to separation—essentially copying the existing organization, systems, and processes—that fails to significantly improve EBITDA. Even when EBITDA optimization is demonstrated on paper, buyers typically apply a contingency in valuation models to account for the possibility that the improvements will not be fully realized.

Because prepackaging the carve-out both optimizes and demonstrates savings, it averts the need for this contingency and should thereby increase the asset’s valuation. However, to avoid destroying value, sellers should ensure that the return on investment for improving EBITDA is positive.

What Are the Advantages?

In addition to demonstrating a concrete improvement in EBITDA, there are several compelling reasons why a company may want to prepackage a carve-out.

Increasing the Buyer Pool. In our survey, M&A professionals said that removing operational uncertainty and demonstrating standalone viability was the most important benefit of prepackaging (as shown in Exhibit 1). Preparing assets in advance reduces the inherent uncertainty of the valuation analysis and the perceived complexity of making the carve-out functional on a standalone basis. Enticing more bidders—such as a larger number of mid-cap PE firms—to compete promotes a higher valuation.

M&A professionals said that removing operational uncertainty and demonstrating standalone viability was the most important benefit of prepackaging.

Reducing Time to Value for Buyers. By shortening the postclosing separation timeframe, prepackaging enables PE firms to capture value faster and thus improves their investment case.

Shortening the Transitional Period. Separation in advance may allow a deal to close without transitional service agreements or with fewer and shorter TSAs, which is attractive for both buyer and seller. Most divestments entail the use of short-term TSAs that allow the deal to close while operational separation is underway. Although TSAs are often necessary to ensure business continuity, they impose constraints and restrictions that the parties would prefer to avoid.

Accelerating Reduction of Stranded Costs. After a carve-out, a parent company incurs stranded costs, leaving it with a proportionately larger cost base. Because prepackaging allows the company to avoid TSAs and the related operational restrictions, it can address stranded costs immediately after closing the sale—without waiting for TSAs to expire.

Accelerating Time to Market for Sellers. Preparing the asset and financials in advance can significantly accelerate the time to market for sellers once they make the formal decision to divest. The period can be reduced to as little as three months, simplifying the seller’s efforts to “time the market.”

Facilitating Public Transactions. Prepackaging assets can help meet the stringent requirements of public transactions. For example, preparing detailed historical pro forma financials for several years can enable sellers to pursue a dual-track process of readying an asset for either a private or a public transaction. This would otherwise not be feasible owing to the long lead times often required to prepare compliant pro forma financials in a large, complex organization.

Accelerating Time to Closing. In some cases, the closing may be delayed if the seller fails to implement certain minimum operational, legal, and IT measures. Prepackaging allows sellers to mitigate some of these closing delays. This shortens the period of uncertainty for employees and customers, reducing business disruption.

What Are the Downsides?

There are also potential disadvantages that companies must consider and mitigate before prepackaging a carve-out. If mitigation is not possible, prepackaging may not be the right move.

Prolonging Uncertainty for the Organization and Customers. Prepackaging may signal to the organization and to customers that a sale is forthcoming—sooner than it would otherwise be disclosed. Moreover, compared with announcing the sale at the signing, prepackaging increases uncertainty because the buyer is not yet known. A prolonged period of uncertainty (even when mitigated by a robust communications strategy) may lead some employees and customers to jump ship, negatively affecting operations, revenues, and morale. The M&A professionals we surveyed cited the turbulence created earlier than necessary as the top reason not to prepackage.

Limiting Options for Buyers. Not all buyers will want prepackaged IT and support functions. Sophisticated private equity buyers, for example, may view it as limiting their options. In addition, for many corporate buyers, replacing an acquired asset’s IT and support functions with their own is a leading synergy in the business case. In such instances, the upfront investment in prepackaged functions will not be reflected in the purchase price. (See “A Practitioner's Perspective.”)

A Practitioner’s Perspective

Bearing More Responsibility for One-Off Costs. Prepackaging means that the seller bears more of the one-off separation costs, which can be significant. In a recent review of approximately 60 carve-outs, we found that the average one-off costs of smaller deals exceeded 5% of the divested company’s revenues.

Losing Synergies. Synergies are typically the business rationale for sharing IT systems and support functions across business units. Because early separation will likely deprive the organization of some of these synergies, sellers must weigh the tradeoff between lost synergies and the benefits of prepackaging. Ultimately, prepackaging will accelerate dissynergies. To eliminate or reduce the effects, the seller will need to adjust its operating model sooner than in the traditional separation timeframe.

Creating Investment Uncertainty. The one-off costs and lost synergies involved in prepackaging constitute investments with uncertain returns, as the seller does not know when or if it will divest the business. This uncertainty may make it challenging to gain leadership support for initiating separation before a final decision to divest.

Deciding Whether to Prepackage

The prepackaging process runs from portfolio review through execution. (See Exhibit 4.) Companies should continually review their business portfolios to identify divestment candidates. For each identified candidate, they should assess the readiness for divestment and evaluate the economics and feasibility of prepackaging well in advance of a transaction. Planning a prepackaging requires a broad set of capabilities and a cross-functional team with representatives from corporate development and M&A teams, business lines, and corporate functions. This composition is similar to that of a transaction execution team.

For companies with numerous assets in the divestment pipeline, standardizing the process in a “prepackaging factory” may be beneficial. This setup promotes the realization of synergies among various prepackaging initiatives.

For prepackaging to be feasible in a specific situation, several fundamental criteria must be met:

- The business is a candidate for divestment within the next two to five years and there is reasonably high certainty of completing a transaction.

- The likely divestment options include a sale to a PE firm, a spinoff, or an initial public offering—not just a sale to a corporate buyer, which will want to integrate the asset and thus may not require standalone capabilities.

- The proposed divestment has a clear scope and perimeter—that is, the seller knows well in advance which businesses, people, and assets are to be included in the deal.

- The separation makes economic sense. The expected financial rewards, such as a higher valuation, are significantly greater than the additional one-off investments borne by the seller and the early loss of synergies.

Determining What to Prepackage

The next step in the process is to develop a blueprint for prepackaging that sets out precisely what to separate, how to do it, and the timing for execution. It is important to bear in mind that prepackaging is not an all-or-nothing or a one-size-fits-all exercise and that full separation is not required before offering the entity for sale. Sellers may choose to separate different areas at different times and prepackage functions to different degrees, on a case-by-case basis.

To inform its choices, the seller should articulate its rationale for prepackaging. If timing is the main concern, for example, it could make sense to focus on items with long lead times for separation, such as IT systems and legal entities. Alternatively, if the main issue is that potential buyers will be concerned about the complexity of separation and the viability of the standalone business, then the seller should consider completing a greater degree of functional and operational separation. Exhibit 5 outlines some of the main considerations when determining which aspects of the business to prepackage.

Far too many companies fail to adequately consider prepackaging carve-outs despite having good visibility into their divestment pipeline. To avoid leaving significant value on the table, companies considering a carve-out in the future should start thinking about the separation process today—well in advance of announcing the intention to divest. Prepackaging a carve-out has many benefits if specific criteria are met. Sellers must carefully evaluate the economics and compare the advantages and disadvantages in each case. Often, they will find that prepackaging is the best way to maximize the value created by a deal.

The authors thank Dana Hughes, Sridhar Kollipara, Jonathan Milde, Rafael Nanawa, Joseph Palackal, Diederik Rothengatter, Wiktor Stevenius, and Alexander Zellner for their contributions to this article.