The transition to a green global economy is gaining momentum as the urgency of addressing climate change grows and the cost of cutting emissions falls.

The momentum is increasing demand for a variety of green products and services, creating opportunities for countries worldwide to spur economic growth in four major areas: critical energy-transition minerals (what we call critical minerals), green technologies (or green tech) manufacturing, green industrial materials, and green services.

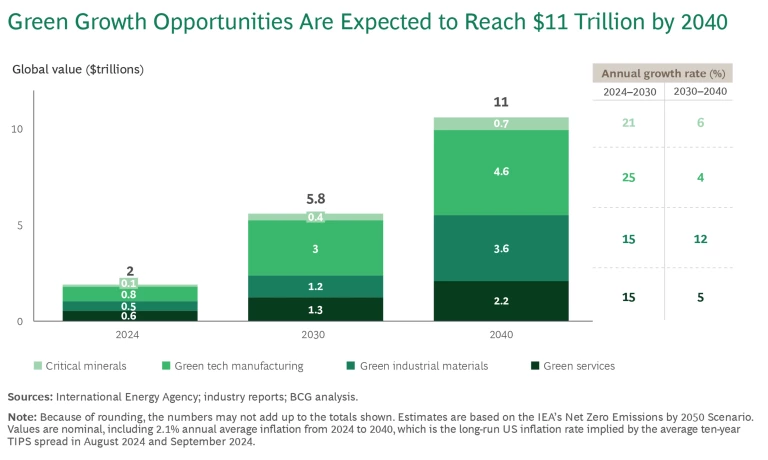

Currently, the combined value of these opportunities stands at $2 trillion. How fast that value increases will depend on policy, technology, and other factors. We estimate that by 2040, the total value could more than quintuple to $11 trillion, which is based on the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario and other sources.

By identifying and pursuing opportunities in the four areas, countries can boost productivity as well as economic growth. But large-scale transitions are rarely smooth, and the green transition is no exception. Evolving technology and competition can threaten long-time industry leaders and cause markets to react sharply, as recent volatility in the automotive and critical-minerals markets has shown.

Countries that act early to capitalize on the opportunities can diversify their economies, position themselves for growth, and capture value that can help them thrive. Each country’s strengths and circumstances should determine which strategies it pursues on the path to success in a greening world.

Opportunities in Four Major Areas

Taking a deep dive into the four major areas shows the status of each and how countries can tap into the combined value. (See the exhibit.)

Critical Minerals

Critical minerals—cobalt, copper, graphite, lithium, nickel, and rare-earth minerals—are fundamental inputs for the batteries, electric motors, electricity networks, and turbines that will power the green transition. Current demand for green uses of critical minerals is valued at about $100 billion and is estimated to grow to $400 billion by 2030, and to almost $700 billion by 2040. Also, by 2040, green end uses are expected to account for 50% of critical-minerals demand.

Achieving success in the mining of critical minerals requires quality resources and a stable regulatory environment. Australia, Chile, China, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Indonesia are the largest critical-minerals producers. Other countries that want to gain a share of the market must be able to meet mining’s high capital demands and long timelines. At the same time, these countries need to limit mining’s impact on the environment and maintain the social license to operate with local communities.

Subscribe to our Public Sector E-Alert.

Refining critical minerals requires expertise, scale, and efficient transportation connections between mines, refineries, and customers. China refines most of the world’s cobalt and lithium, and its refineries are located close to its end customers in the country’s battery and electric vehicle (EV) production hubs.

Countries rich in natural resources have a window of opportunity to expand mining and move further into refining. The European Union’s Critical Raw Materials Act and the clean energy incentives passed in the US in 2022 include provisions aimed at diversifying imported critical-minerals sources. Indonesia put in place policies, including a ban on unrefined nickel exports, that boosted its share of global refining from 16% in 2019 to 41% in 2023. Governments in Africa, Australia, and Latin America are also taking steps to expand critical-minerals production and extend their activity along the value chain. Their success will turn on whether they can build cost-effective processing and logistics operations, manage environmental challenges, and secure offtake agreements with resource producers for their future output.

Green Tech Manufacturing

We define green tech as the technologies and equipment required to decarbonize the global economy. Technologies and equipment such as wind turbines, solar photovoltaic panels and batteries, heat pumps, and hydrogen electrolyzers produce renewable energy, while others such as electric vehicles and batteries reduce carbon emissions.

Green tech manufacturing is the largest of the four opportunity areas, and it is expected to remain so.

Green tech manufacturing is currently the largest of the four opportunity areas, and as it grows, it is expected to remain the largest. In 2024, the global value of green tech manufacturing is an estimated $800 billion. Assuming that countries follow a path to net zero by 2050, the value of green tech manufacturing is expected to reach $3 trillion worldwide by 2030 and hit approximately $4.6 trillion by 2040.

Green tech manufacturing opportunities can be divided into three categories.

Mature Modular Products. Incumbents dominate established green tech manufacturing markets, including those for solar photovoltaic panels and batteries. China produces more than 80% of the world’s solar panels and batteries, and the country continues to invest in the industry. In 2023, China accounted for approximately three-quarters of the $200 billion invested in the manufacturing of modular products worldwide, with the EU and US responsible for about 16%. As markets for modular products continue to grow, incumbents’ overwhelming market share gives them a cost advantage that new entrants could find tough to crack.

Engineered Products. Competition is shifting within the engineered products category, which includes EVs, heat pumps, and heavy machinery. As global demand for green products grows, countries with existing manufacturing operations in this category are looking to switch to making green versions of what they produce.

China made such a change, and in 2023, it became the world’s largest exporter of EVs, overtaking Japan and Germany. The switch came about because government policy and cost-effective manufacturing encouraged large-scale investment in EV and lithium-ion battery production.

Other countries are adopting policies to attract EV manufacturing. One is Thailand, which aims to have 30% of all vehicles produced in the country to be electric by 2030, and it is offering global EV manufacturers tax incentives to set up shop there. Brazil and Vietnam are implementing similar measures. To encourage local assembly, both countries are offering makers of EV components and machinery a mix of subsidies, tax breaks, and import duty reductions.

Industrial Equipment. Countries are still in the early phases of developing and commercializing equipment for industrial decarbonization . Such equipment enables low-emissions industrial processes and the production of materials such as green hydrogen and green steel.

Given the technical complexity and high capital investment that green industrial equipment innovations require, countries with established R&D bases and industries are well positioned to lead and stand to benefit the most. Achieving success will take strong policy support, international collaboration, and ongoing innovation to drive down costs.

Green Industrial Materials

The global economy will need decarbonized versions of metals, basic chemicals, plastics, glass, ceramics, and other industrial materials. It will also need to produce green hydrogen for transportation, industry, and power. Currently, green industrial materials make up a fraction of the total market: only $500 million of $3.5 trillion. However, as countries follow a path to net zero by 2050, the market for green industrial materials is expected to grow to $1.2 trillion by 2030 and $3.6 trillion by 2040.

The countries that are market leaders in industrial materials are well positioned to transition into green versions of the same, but they will need to overcome many hurdles to do so. For example, the technologies required to produce green industrial materials are still developing and scaling them is a long-term challenge. In addition, the path countries take may depend on their current technology base. Because European countries have a higher concentration of electric arc furnaces for steel production, they are likelier to switch to using hydrogen-based direct reduced iron technology to make green steel. By contrast, countries such as China and India that commonly use newer blast furnaces to make steel may find carbon capture and storage technology a more practical option for producing green steel, at least initially.

To switch to producing green industrial materials, countries will also need to upgrade or build new infrastructure. Many are accelerating the deployment of renewable electricity generation, networks, and storage. Countries are also exploring new energy options. Both Germany and Japan are backing national hydrogen infrastructure, including production and import facilities and storage and distribution networks.

To gain a competitive edge, countries will need to include green industrial infrastructure in their long-term strategic plan and develop new models for public-private partnerships to align incentives and share risks. They will also need to streamline regulations and infrastructure approval processes.

To gain a competitive edge in green industrial materials, countries need to develop new models for public-private partnerships.

Addressing the cost of green industrial materials will be another task. These materials can cost more, which can curtail demand. Governments can use policies and incentives to stimulate demand and to support producers so that they can scale their operations and reduce costs. In the US, the federal government’s Buy Clean Initiative uses public procurement to catalyze private sector investment in green building materials. Developing standards and certifications for green industrial materials can also build the trust with consumers and the private sector that’s needed to cultivate a new market. In addition, expanding carbon pricing mechanisms, such as the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, can level the playing field among countries and strengthen demand for green industrial materials.

Green Services

The shift to a green economy will boost demand for a variety of green services, including financing to support the transition, IT services, eco-tourism, and low-emissions air travel. The shift will also increase public and private investments in climate adaptation and resilience projects, as well as in nature-based solutions such as carbon sequestration.

The global market for green services is already worth about $600 billion and is expected to more than double by 2030, to $1.3 trillion, and exceed $2.2 trillion by 2040.

Financial Services. The need to invest in decarbonization , climate adaptation, and nature-based solutions is expected to create a significant, growing demand for lending, risk management , and market making. Green banking assets are likely to triple to more than $4.5 trillion by 2030 and generate more than $75 billion in annual net interest income. By 2040, both assets and revenue could double again. The transition also is creating demand for nonlending services, including climate risk assessments , carbon accounting and disclosure, and carbon markets . Countries with existing financial centers are well positioned to capitalize on this opportunity.

IT Services. Climate- and energy-transition software and AI solutions have grown to a $40 billion global market for such diverse needs as carbon accounting, energy controls for buildings, and management of energy grids . Countries with data centers powered by low-cost, low-emissions electricity can maintain a competitive advantage.

Tourism and Transportation. Ecotourism and sustainable aviation are two major green services opportunities. International ecotourism is already a $70 billion market. As ecotourism and sustainable air travel advance toward net zero by 2050, these markets could exceed $250 billion by 2030 and $750 billion by 2040.

Climate Adaptation and Resilience. Adapting infrastructure, weather monitoring, agriculture, and other systems to be resilient in the face of climate change is creating opportunities that are expected to grow to approximately $300 billion by 2030, and to $450 billion by 2040. It’s expected that investments in climate adaptation will lead to economic, social, and environmental benefits that are valued at roughly four times the cost—one reason why demand is likely to be strong.

Nature-Based Solutions. Annual expenditures by the public and private sectors on nature-based solutions to combat climate change are expected to exceed $500 billion by 2030. Nature-based solutions include carbon sequestration, biodiversity offsets and ecosystem services, sustainable forestry and reforestation, and soil restoration. Countries that gain expertise in the needed tools and technologies, and in the development and management of natural assets, can be well placed to export that knowledge and derive ongoing revenue from these growing markets.

Countries Must Chart Their Own Course

Countries that want to compete in fast-evolving green markets must develop viable positions. To do so, they typically will need to combine broad incentives (such as carbon pricing), programs to decarbonize electricity grids, and industrial policies to nurture nascent green sectors. Trade policies, including cooperation with other green leaders, can help level the playing field for green products and services.

However, there is no single approach. Each country must develop policies to capitalize on its specific strengths and circumstances. And green growth strategies are different for different economies, whether resource based, advanced, or emerging.

Resource-based economies should pursue green growth. Countries with economies based on abundant natural resources can pursue growth opportunities for green exports, including for critical minerals and green industrial materials such as green steel. Many existing resource exporters have the advantage of strong revenues and a healthy balance sheet, and some have excellent prospects for cost leadership in low-carbon electricity.

Resource exporters should play to their strengths in mining and expand into processing where they have competitive potential, partnering as needed for technology transfer. To motivate private investment in low-carbon energy and process industries, governments may need to co-invest. Countries with resource-based economies can also use broad-based carbon pricing to help shape incentives and maintain export market access as trade partners tighten standards.

Advanced economies must strengthen competitiveness. The world’s more advanced economies have diverse green growth opportunities in green tech manufacturing, green industrial materials, and green services. But in some of these economies, manufacturing industries have struggled to match the green innovations of global rivals. To become more competitive, these countries can invest in green tech manufacturing and green industrial materials innovation. To compete in green industrial materials, advanced economies will need to cut green energy costs and mobilize investment.

Tariffs and production subsidies can buy time for a transition. But such measures should be used sparingly, as they can slow adoption, harm consumers and downstream sectors, and risk retaliation from trading partners. Smaller advanced economies often have more to gain from specialization, so they should be highly selective about the opportunities they pursue.

Emerging economies should provide incentives for investment and partnership. The world’s emerging economies are diverse, with a correspondingly distinct set of green growth opportunities. They should shape incentives to shift private sector investments to green opportunities. They should also cultivate foreign direct investment for technology transfer and pursue strategic partnerships to secure market access. For larger emerging economies, supporting domestic markets can attract suppliers and help local producers scale up. Because emerging economies can be highly exposed to climate change damages, investing in climate adaptation and resilience should also be a top green-growth priority.

The shift to a green economy is creating significant opportunities for countries everywhere. Countries must make decisions informed by their strengths and circumstances so that they have the potential to create a competitive advantage. By identifying and acting on the right opportunities now, they can put themselves in the best position for growth in a greening world economy.

The authors would like to thank Keith Halliday, Jan Koeleman, Varad Pande, Rebecca Russell, and Anthony Smith for their contributions to this article.