For most CEOs, cutting costs is relatively straightforward. It’s far harder to prevent those same costs—or new ones—from rising again over time. We recently surveyed nearly 2,100 business leaders worldwide, all of whom had undergone a cost transformation in the past five years. (See “About the Research.”) The results are sobering. Costs are the top organizational priority, yet three-fourths of respondents say their cost program didn’t hit its goals. Most have launched programs repeatedly, putting stress on the organization and undermining management’s credibility.

About the Research

Why? Often, it’s because cost initiatives look at superficial measures without addressing the underlying organizational causes—akin to treating a patient’s symptoms, rather than the disease. As a result, roles that are supposed to go away don’t, administrative processes multiply, and a year or two later, companies need to launch yet another cost program.

Addressing costs in a more sustainable, holistic way requires changing behaviors and organizational dynamics—the real issues that lead to costs creeping back. More specifically, companies need to address four evergreen cost drivers that we see again and again in our work with clients, all grounded in rational behavioral economics. Many of the practices that undermine sustained cost savings programs may make sense at a micro level for individuals and managers across the workforce, but they don’t support the programs’ overarching goals.

The good news is that companies that confront these four issues head-on are far more successful in reducing costs sustainably. These firms emerge from their cost transformation programs with a streamlined organization, fewer management layers and bureaucracy, and the agility to pivot resources to fuel growth and meet other demands in the future. In other words, they no longer need to launch cost programs every few years. Instead, they have a hardwired operating model that gives them a competitive advantage.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on people strategy

Key Survey Findings

Our survey of business leaders and managers around the world revealed several key findings:

- Cost was the top organizational priority, ranked first by 35% of respondents, followed by productivity enhancement (21%), top-line growth (20%), and adopting new technology, including GenAI (16%).

- Only one-fourth of respondents described their cost program as “very successful.”

- Half of all respondents said that their companies pursue cost programs every one to two years.

These findings are not outliers; other BCG research has reached similar conclusions, with only about half of C-level executives saying that cost efforts created lasting change at their company. Yet they are still surprising, given that the basic elements of a cost reduction program are widely recognized. Companies know how to reduce costs—measures like stricter budgeting, first-order control mechanisms over spending, and reducing headcount are hardly new. But these actions will fail in the long run if firms don’t change the organizational context so that individuals make decisions in line with the program’s goals. Otherwise, as soon as the program is complete, leaders revert to their previous, rational behaviors, such as adding incremental positions to solve new business challenges—and costs creep upward once more.

To shift the context and create new behaviors, companies need to undergo an organizational reset. In other words, they need to focus on both the “what” and the “how” of a cost transformation.

Four Evergreen Cost Drivers

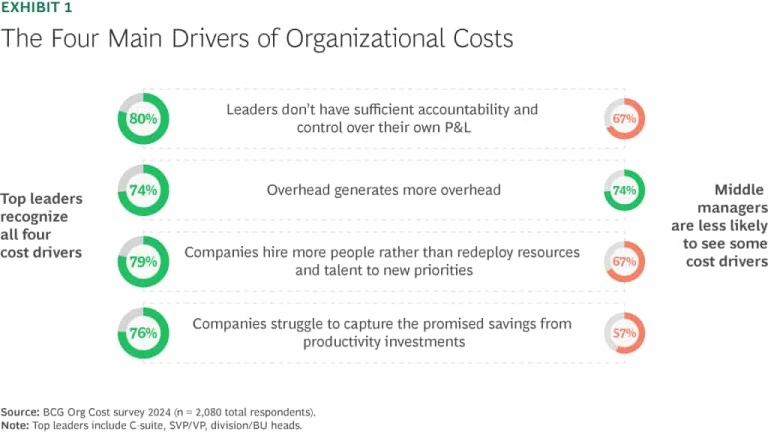

From our client experience—confirmed by the quantitative research—four pervasive organizational dynamics create persistent cost pressure that cannot be overcome by simplistic, control-based measures. These drivers were identified by both senior leaders and middle managers in our survey. (See Exhibit 1.) The findings underscore an uncomfortable truth: no cost program can sustainably succeed unless companies address the underlying behaviors that lead to cost creep.

Leaders don’t have sufficient performance accountability for their P&L. The first reason that so many cost programs fail is that many leaders don’t have direct P&L responsibility. They have their own objectives, and a persistent desire for resources to meet those objectives—making absolute cost someone else’s problem. In our survey, the lack of P&L responsibility was cited by 80% of senior leaders and 67% of middle managers as a driver of cost creep.

Lack of P&L responsibility was cited by 80% of senior leaders as a driver of cost creep.

For example, one manufacturer runs programs to reduce general and administrative (G&A) costs every two years. But regional business leaders have learned this cadence and work around it, continuing to hire new people and building up a buffer for the next cost program, which they know is coming soon.

To solve this issue, companies should assign clear P&L accountability, including both profit and cost reduction goals, to business leaders, along with the reasonable autonomy to achieve those targets according to their judgment. At most organizations, this will require redesigning the operating model and instituting strong incentives to motivate leaders to secure absolute savings rather than perform against negotiable targets. In addition, performance accountability needs to cascade from top leaders to lower levels; this will embed cost awareness and give people the proper incentives and decision rights to support the company’s overall profit and cost targets.

Overhead generates more overhead. The second main cost driver is the way that leadership layers and support functions become more inflated and bureaucratic over time—a process that 74% of both senior leaders and middle managers in our survey observed. In many cases, solutions tend to make the problem worse. Companies tend to address emerging issues by creating new committees, processes, and managers, leading to more costs and complexity. Often, these actions reflect internal competition—supervisory or compliance roles trigger business units to respond by creating their own mirror roles, and the bureaucracy spreads.

For example, a services firm froze non-critical hiring, but it instituted a formal approval process so that the CHRO and CFO could determine critical versus non-critical hires. The company created a new central team to evaluate approvals, and business units in turn created their own teams to justify bringing new people on board. Ultimately, most business teams ended up hiring the people they wanted and the company was left with a new layer of bureaucracy, a new time-consuming core process, and no sustained progress toward the original goal of reducing the size of the workforce.

To avert this outcome, companies need to aggressively cut bureaucracy, overhead, and low-value work. That entails disproportionately shrinking the size of support functions through staffing reductions or assigning those resources directly to P&L owners, creating more transparency for decision makers. They also need to increase the managers’ spans of control, thin out layers of middle management, and take a hard look at all overhead work processes to determine which of them can simply be stopped.

Companies hire more people rather than redeploy resources and talent to new priorities. When companies pursue a new opportunity, their initial impulse is to create incremental roles and structures rather than transferring or repurposing positions and funding from existing work groups. Among survey respondents, 79% of top leaders and 67% of middle managers identified this issue in their company. The organizational model at most companies isn’t built to flexibly pivot resources. Moreover, leaders often benefit from empire building, so it’s irrational for them to actively cooperate in resource transfers.

One large consumer goods company implemented a new product strategy focused on digital and data-driven features. But the business units developing legacy products weren’t willing to reduce their pipeline to offset the needed investment. Rather than shifting budget and positions to the new priorities, the company added significant headcount spend.

To address this issue, companies need to revamp the operating model and governance processes to make it easier to shift resources to higher-priority areas. Leaders must be able—and incentivized—to put the brakes on activities that no longer align with the company’s direction and follow through to ensure the work is removed and resources reduced. In addition, employees need to be enabled and supported to move into new roles. Firms can do this by developing strong upskilling and reskilling capabilities, as well as maintaining an up-to-date inventory of employee skills, to enable talent mobility.

Leaders must be able—and incentivized—to put the brakes on activities that no longer align with the company’s direction.

Companies struggle to capture the promised savings from productivity investments. Organizations in all industries are investing in productivity solutions, including new technologies like digital, AI, and automation. These initiatives hold massive savings potential, but often the gains don’t materialize and translate to a leaner organization—a pattern reported by 76% of senior leaders and 57% of middle managers in our survey.

One large technology company repeatedly tried to launch productivity and cost-savings initiatives without success. It invested to implement productivity-enhancing systems and processes, but spending did not decrease. A key reason was that after labor productivity increased, leaders did not follow through and eliminate superfluous positions; instead, they used those freed-up man-hours on other priorities. Only when leaders performed a detailed organization redesign—eliminating positions and reshaping roles and accountabilities—did the company capture expected savings.

To more effectively lock in the benefits from productivity investments, companies should look beyond projections and develop concrete plans to capture hard savings, along with measures to track and monitor the realization of those savings. Companies should also redesign processes and roles to incorporate the new technology, reducing or redeploying resources as needed.

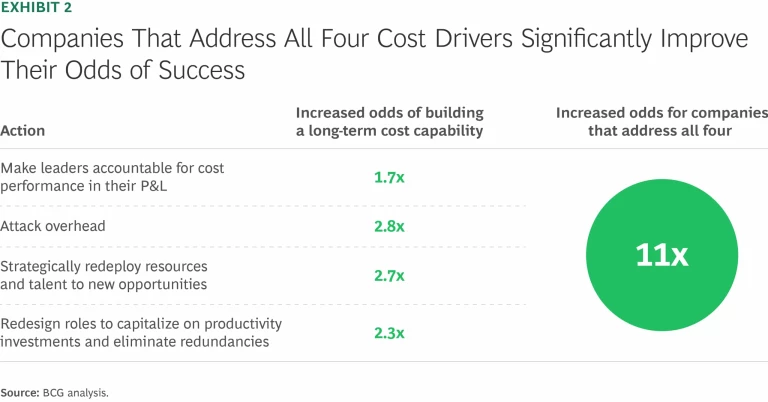

In our survey results, companies that address each of the four evergreen cost drivers can improve their odds of building a long-term cost capability by a factor of two to three. And addressing all four simultaneously creates a significant multiplier effect. (See Exhibit 2.)

Addressing the "How" of Sustained Cost Transformation

Across all four cost drivers, companies need to focus on the “how” as much as the “what.” One priority is organizational alignment. Our survey data shows frequent misalignment between senior leaders, who generally understand the need for a cost program, and middle management, who often feel that cost initiatives are “being done to them.” To the degree possible, middle managers should have ownership in the process of redesigning the organization, along with real accountability for targets and future costs.

In addition, companies should identify a minimally sufficient set of KPIs that drive value and spur cost-oriented behavior. These need to be clear, quantifiable, and transparently reported, so that managers and employees understand how the company and each unit is performing relative to its cost targets.

The redesign should establish clear accountabilities and decision rights with a focus on enabling cost-conscious decisions and addressing tradeoffs. And finally, companies should incorporate a cohesive change-management program to articulate and embed value-oriented mindsets and generate employee engagement during and after the process.

How One Company Generated $1 Billion in Savings

Consider a global health care company that had seen a substantial decline in revenues. It launched an ambitious program to reduce its costs and reallocate some of those resources toward several promising new product lines. Achieving that goal entailed developing changes to the operating model, shifting resources out of legacy businesses into growth areas, and upgrading talent throughout the company, among other priorities.

To ensure that the program would succeed, leaders addressed all four of the major evergreen cost drivers:

- To bolster value and financial ownership, the company made changes to the operating model to enhance P&L accountability and resource control of the business units. It also redesigned roles and accountabilities deep into the organization so that middle managers would understand their role in achieving the strategic agenda and value objectives.

- To preclude growth in overhead, the company moved some resources and decision rights away from centralized functions and into the business units. As part of that process, the firm concretely reduced low-value-add activities, took out two management layers, increased spans of managerial control, and streamlined G&A.

- Leaders cut resources substantially in legacy-product businesses and the functions that supported them, with some work-groups being reduced by as much as 50%. To support the new strategic direction, the firm redeployed existing talent to staff the new teams, planning to selectively hire from the outside to fill the most critical skill gaps. The HR function developed a baseline of employee capabilities that enabled managers to identify high-potential talent across functions and countries to fill roles.

- In the detailed design phase of the program, executives and managers rigorously reviewed every position in every work group to ensure savings would be secured through reducing activities and enhancing productivity. Throughout the implementation, leaders followed through on headcount initiatives to ensure staffing levels aligned to business-case commitments.

In the program’s first year, the company has exceeded management’s cost and margin objectives, delivering more than $1 billion in gross cost savings, of which 25% was reallocated into growth areas. Equally important, the organization is more efficient, agile, and responsive to changing market dynamics, with more autonomy pushed down to the local level.

The imperative to reduce costs is only growing, and companies using the approaches they have relied on in the past will fall short. To successfully curb costs, they need to address the four drivers we’ve identified and focus both on what they change and how they change it. In that way, they can alter the underlying behaviors and processes, make sustainable cost reductions, and give themselves a lasting advantage over the competition.