Climate change is prompting many governments to transition their energy systems and decarbonize their industries. The global green transition represents an economic opportunity for those countries that provide the tradable green commodities, technologies, and the products and services required to deliver it. Currently, the combined value of these opportunities stands at $2 trillion. How fast that value increases will depend on policy, technology, and other factors. We have estimated that by 2040 the total value could more than quintuple to $11 trillion.

Policymakers are playing an active role in pursuit of this opportunity through direct investment, economic incentives, and other policy measures. They are also encouraging the agglomeration of research capabilities, technical skills, critical infrastructure, and other factors into green growth ecosystems that hold greater competitive advantage than the sum of their parts. This article examines the principal levers and key success factors for doing so.

What Are Green Growth Ecosystems?

Ecosystems are “critical masses” of linked players—including companies and institutions across the value chain—that collaborate to enable the production of goods and services, and unlock and sustain competitive advantage.

Not all green ecosystems are alike. They can differ widely in their starting point:

- They can be built from scratch to focus on green technologies and products or can be traditional industrial activities transitioning toward a clean footprint and business model.

- Their focus can be on multiple value chains, some value chain segments, specific products, or services.

- They may have greater or more limited initial access to critical infrastructure and competitive resources such as financing, technology, and natural endowments (for example, lithium deposits).

Different types of ecosystems require different types of support.

Policy Levers for Green Growth Ecosystems

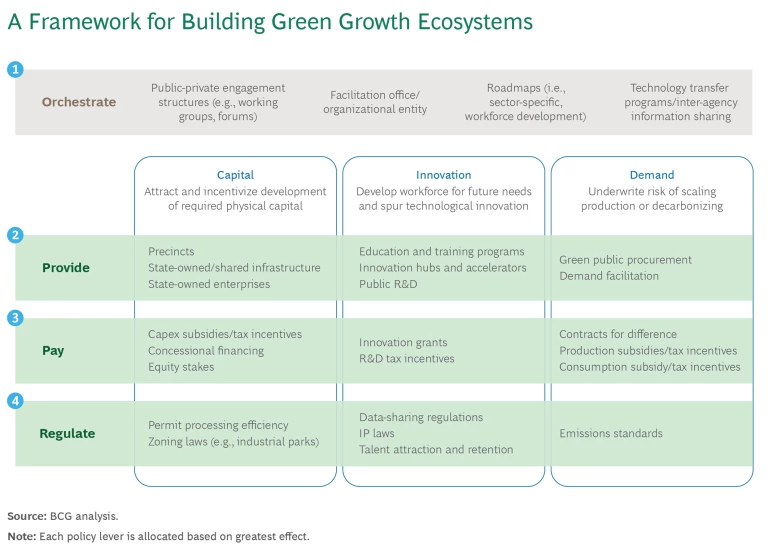

Policymakers have an invaluable role to play in catalyzing green-growth ecosystems that attract private-sector investment. We have distilled the key policies into a framework in the exhibit. First and foremost, policymakers should focus government efforts on the following:

- Orchestrate the various stakeholders into coordinated planning and delivery.

- Provide capital, innovation, or demand via procurement mechanisms.

- Pay others to finance, innovate, or purchase through financial mechanisms.

- Regulate to create the enabling conditions.

Of course, many other policies not specifically related to ecosystems like trade policy and competition policy will have an impact but are not covered here.

In our discussions, practitioners underscored that the foundational first step for driving ecosystem success is building productive collaboration between ecosystem players, and between players and government. Typically, a central engagement office will run regular working groups, industry forums, and other processes to inform and shape the ecosystem. Frequent, ongoing consultation and collaboration are also common, as managers monitor and adapt to changing opportunities.

Orchestrate. The Basque Country in Spain and the Humber CCS cluster in the UK exemplify effective orchestration.

The Basque Country government works closely with private industry, academia, and research institutions through the Basque Net Zero Industrial Super Cluster to support economic development while working to achieve net zero by 2050. The Basque Country cluster model, set up in the early 1990s, brings together private sector players across value chains and policymakers in more than 15 cluster organizations. These organizations are formal entities responsible for strategic planning that serve as a priority sharing forum and help the regional government identify specific policy constraints to support competitiveness and ecosystem growth. In this way, the Basque Country has identified opportunities and deployed tax incentives for capital investment and grants for R&D. Reflecting the small and medium-sized business industry base, the Basque region also provides education and training programs, and innovation hubs and accelerators to focus on the technologies that industry has identified as top priority for the transition. This governance model has become a reference point for other regions around the world.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on the public sector

In the Humber region, companies, industry groups, trade unions, and the UK government have built a plan to cut emissions by 3 to 4 million tons per year and to deliver hydrogen projects. A central challenge faced was to shape incentives to build a new carbon capture and storage (CCS) infrastructure ecosystem, as it required coordinated investments by multiple parties across carbon capture, cooling and compression, pipelines, and storage infrastructure. Participants helped inform the design of revenue models to make the required investments viable. For example, energy and industrial emitters were exposed to unknown future emissions pricing, introducing material risk to the viability of carbon capture investments.

Beyond orchestration governments should provide, pay for and regulate the three building blocks that underpin successful ecosystems: capital, innovation, and demand. Taking each building block in turn: ecosystems require capital, both physical capital (for example, office parks, grid connections, mining infrastructure) and financial capital. Creating the conditions for capital can be the most important role of policymakers beyond orchestration. Green growth ecosystems also rely on innovation, including skilled workforce and new technologies, particularly those with high knowledge- and technology-intensity. For example, solar photovoltaic development and production requires advanced R&D in material science and high-tech manufacturing. Finally, green growth ecosystems cannot be sustained without demand for their goods and services, whether domestic or international, public or private. Of course, some of the most successful ecosystems were established ahead of demand, for example, China’s new electric vehicle program began in 2009, a year that saw fewer than 500 electric vehicles (EVs) sold in China.

All three building blocks are critical, but the emphasis will vary between ecosystems. For example, a green financial services ecosystem will place particular emphasis on innovation, while a new mining ecosystem will emphasize new physical capital. Moreover, policymakers should focus on the market failures. For example, an ecosystem may be flooded with financial capital but may have a gap in access to technology. Identifying the key challenges and appropriate levers is a key objective of orchestration activities.

Policymakers then have three key levers to lay those building blocks:

- Provide levers are where the government directly provides physical capital, innovation, or demand. For capital, government can address gaps in critical infrastructure by directly providing infrastructure itself. The government can also provide innovation and skills via education and training programs or public R&D programs. And it can support demand directly by purchasing the goods and services produced by the ecosystem. For example, the government can provide state-owned land for development, as the Crown Estate has done in the UK for offshore wind development, or it could use state-owned enterprises to build infrastructure, as China has done for EV chargers.

- Pay levers, by contrast, are where the government uses public funding to support private sector activity. It can support capital investments through concessional financing, guarantees, and equity stakes for pre-commercial technologies; innovation through R&D tax incentives and grants; and demand by incentivizing private purchases. For example, Sweden paid €265 million to support the construction of a green steel plant in northern Sweden as part of its H2 Green Steel project.

- Regulate levers involve creating clear and efficient laws and regulations, which are critical to remove barriers to deployment and to enable ecosystems to operate effectively. For example, governments could accelerate capital investment with fast permitting for developments; promote innovation by protecting intellectual property and designing an effective visa system to attract talent; and stimulate demand by setting product standards which support uptake. For example, China waived much of the car registration process for customers purchasing EVs, a notoriously long and expensive process for gas-powered cars.

These three levers are often used in combination. For example, governments typically use both pay and provide options to support innovation, such as through innovation hubs to bring together universities, government agencies, and private companies, all supported by R&D grants. Similarly, for technologies in early adoption phases, stimulating demand through pay levers, such as consumer incentives, and through provide levers, such as public procurement, helps address the “chicken-or-egg” supply-and-demand problem that often hinders clean tech innovation.

China provides an example of new green ecosystem building, becoming the world’s leader in EV battery production: China is responsible for ~60% of electric global EV production and accounted for over 50% of EV sales globally in 2023.

Pay for capital, innovation, and demand, investing in EVs in the early 2000s when the EV industry and EV infrastructure were still emerging. They invested in physical capital to develop the full EV value chain, right through to final vehicle assembly, and provided substantial government support for innovation. And through use of substantial incentives, they stimulated demand among millions of drivers. Together, these policies helped battery and vehicle companies develop scale.

Provide physical capital, namely, a major EV charging network developed by state-owned enterprises, such as the State Grid Corporation, that together with private partners have rolled out 10 million chargers in the last 15 years. The state also provided demand through public procurement, such as establishing EV bus networks.

Regulate to maintain competitive pressure, permitting lagging firms to fail or be acquired, and support Tesla’s entry into China, expediting the land acquisition and the construction permitting for its major capital projects. Together, these policies formed a powerful combination enabling China to become the world’s foremost EV manufacturer and market.

The US’ hydrogen hubs, including California’s ARCHES H2 hub, provide examples of developing new greentech ecosystems. In California, a group of organizations made up of state offices, private partners, NGOs, and universities applied to a federal fund directed at creating seven new hydrogen hubs nationally. Their goal: to develop the California state-wide ARCHES H2 hub focused on green hydrogen.

Orchestrate. Given the early state of the technology and large infrastructure needs, collaboration was needed. So, California established the Alliance for Renewable Clean Hydrogen Energy Systems (ARCHES) as a public-private partnership between the state (for example, the California Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development, the legislature, local government), higher education (for example, the University of California—the public research university system—and two affiliated laboratories), industry, nonprofits, community groups, and organized labor. Together, they created a plan for the hub, addressed coordination problems across production, distribution, and demand, and submitted a single, state-wide application for federal funding.

Pay. The government funded physical capital, namely, hub construction, requiring a 1:1 cost share, bringing in private and other public funds. Collaboration in innovation has started at the federal level, with the US Department of Energy’s Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies Office supporting research consortiums to find a way to reduce the cost of hydrogen to $1 per kilogram by 2035. To support development of this emerging technology (innovation) and infrastructure (capital), the state of California is also co-funding shared infrastructure for a hydrogen fuel station network.

Provide. The government is providing demand, using public procurement to purchase hydrogen vehicles, such as through hydrogen municipal vehicle pilots.

Regulate. Another critical enabler is clarifying regulatory requirements, such as those defining green hydrogen, to reduce uncertainty and risk for potential implementors. California is also stimulating demand with the Innovative Clean Transit rule, which requires public transit agencies to purchase only zero-emission buses from 2029.

In this way, California is using each key lever—orchestrate, pay, provide, and regulate—to create the conditions for success for its hydrogen hub.

Practical Principles for Ecosystem Management

Six overarching lessons emerge from our engagement with ecosystem players and policymakers who have championed new green ecosystems.

- Identify and leverage the ecosystem’s “right to win.” When identifying the ecosystem’s economic benefits and key areas for green growth, it is crucial to consider and leverage the ecosystem’s competitive advantages. In Indonesia, the government leveraged its natural resources in nickel required for the green transition to incentivize downstream development. Similarly, Brazil and Australia have utilized their renewable energy resources to help decarbonize mining critical for the green transition and downstream industries like steel.

7 7 Sarah MacNamara, “Pilbara Transmission Line Progresses,” Energy, August 12, 2024; “Harnessing Renewables to Decarbonise the Pilbara,” RioTinto website. The Basque region has built a competitive advantage for its new green ecosystem by leveraging its existing manufacturing capabilities. In Humber, the availability of traditional products (such as steel) that are used in greentech products (for example, wind turbine blades) have attracted new greentech companies to the area. One example is the Siemens Gamesa wind turbine blade facility. This is especially the case when those traditional products are being decarbonized, as British Steel is doing via two new electric arc furnaces. - Understand the obstacles to unlocking ecosystem value and design incentives accordingly. Policymakers must work to understand where and how value is created in the ecosystem, and what drives the economics of different participants, by engaging industry partners. Policymakers can use these insights to target the right activities and investments, and design incentives to make them privately investible. For example, the UK government established four separate working groups to inform the design of bespoke business models to provide incentives for carbon capture and storage investments across the Humber industrial ecosystem.

- Deploy the full range of policy instruments. Governments should think broadly about how public sector assets and capabilities can support emerging ecosystems. Some have contributed access to land, invested in utility connections, or prioritized public sector research to drive specific ecosystems. Targeted changes to regulation and permitting can remove delays and boost returns to private investment without costly incentives. For example, the Indonesian government leveraged the country’s position as a critical nickel exporter to negotiate battery and EV supply chain investments and transfer of technology agreements. When Tesla was interested in building its Gigafactory in Shanghai, the Shanghai government expedited the land acquisition and construction permitting process, allowing construction of the 860,000 square meter facility in just 10 months. Tesla’s move strengthened China’s EV ecosystem, with the Gigafactory spurring domestic companies to compete with Tesla. Governments are also critical channels of support through public procurement and channeling public funding and multilateral support, de-risking investments and helping to reduce the cost of capital. As these examples show, which lever the government focuses on depends on circumstance and, in particular, which key enablers are missing. For example, a region with access to deep, liquid capital markets but with slow permitting may need to focus on improving regulation rather than paying for concessional finance. Governments should think about all the policy levers but may be selective about which to pull.

- Plan, but engage with industry to monitor and adapt as you go. Governments need to strike a balance between planning and flexibility. They should expect to iterate as the ecosystem develops, so ongoing structured engagement is key. And they should make sure to develop clear, comprehensive yet simple KPIs to track progress, act through implementation and change course if necessary. The Massachusetts Clean Energy Center, a quasi-public state agency managing the development of a clean energy ecosystem, has kept its programs flexible, adapting to participant feedback and performance reviews. For example, it has adjusted its Catalyst Program’s grant amounts, eligibility criteria and scope to better support early-stage startups. In Peru and other Latin American countries, governments have set up public-private roundtables, mesas ejecutivas, to exchange information about blockers to business development and investment, small and medium-size enterprise growth, and align on tangible measures and steps to unlock growth potential in strategic sectors.

- Orchestrate the ecosystem, but don’t play all the parts. Governments should seek to coordinate, not dominate the ecosystem, and target efforts where government can add unique value. Many ecosystems are highly decentralized, and participants often have strong capabilities. For example, the Basque Country government defines an overarching vision for Spain’s Basque Industrial Super Cluster based in extensive industry engagement, and each of 16 clusters retains responsibility for creating and executing on its own cluster strategy. Similarly, Netherlands’ Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate identified that progress in the energy transition was slowed down by a lack of data sharing between industrial energy users and grid operators due to the confidentiality of commercially sensitive information. The ministry therefore supported the setup of a “Data Safe House” to help coordinate the sharing of energy and sustainability investment plans in a trusted way.

8 8 “Over Data Safe House,” Data Safe House website. - Commit to backing an ecosystem for the long term. Consistent engagement is key to giving ecosystem participants the confidence to make their own long-term commitments. The Chinese government’s commitment to electric vehicle ecosystem over more than two decades, from lithium and rare earths through batteries to vehicle production, has been central to the growth of the sector. Similarly, Denmark’s leadership in wind turbine technology has been the result of a three-decade commitment to development of the ecosystem by government, with support mechanisms evolving from R&D and production incentives in the early years to a greater emphasis now on market facilitation and supportive regulation.

Increasingly, governments are recognizing that they can use the power of ecosystems to unleash green growth and position their economies to capture opportunities in a decarbonizing global economy. As governments work with private and nonprofit organizations to advance the global green transition, the practical experience of policymakers around the world offers a guide on how to embed evidence-based planning in their efforts.

The authors thank their colleagues Keith Halliday, Kaushick Maheshwaran, Jim Minifie, Madeleine Neiman, Tommy Peto, and Arya Prabha for their valuable insights and thoughtful feedback on this article.