This article is part of a series examining the competitive outlook for key global process industries and how they can prosper in an uncertain future.

Demand for the critical minerals needed to power the energy transition is skyrocketing. Meanwhile, the mining industry is contending with depleted mineral deposits, chronic underinvestment, and environmental and social risks . Rising geopolitical tensions further threaten trade flows and exacerbate the supply gap. And this gap doesn’t just affect the shift to a green economy—it has important implications for advanced technologies as well as broad swaths of the manufacturing sector and industrial base. (Consider, for example, the gargantuan needs of AI and data centers.)

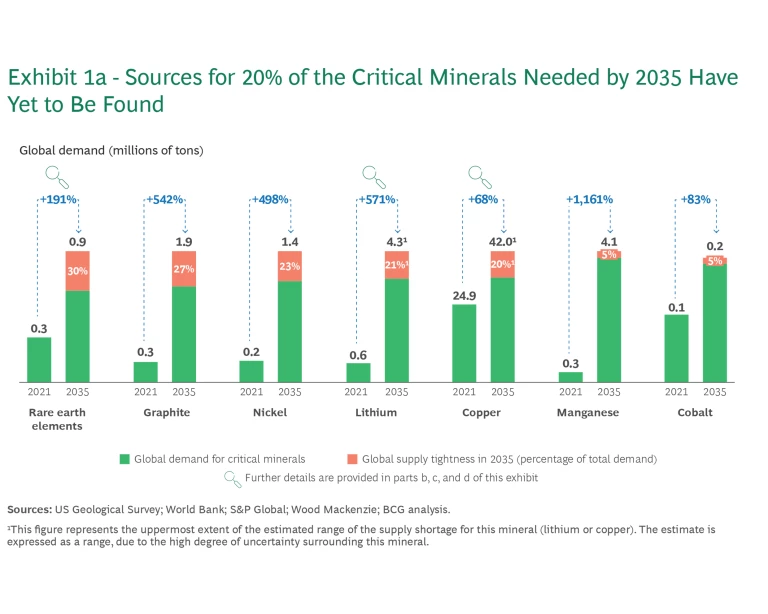

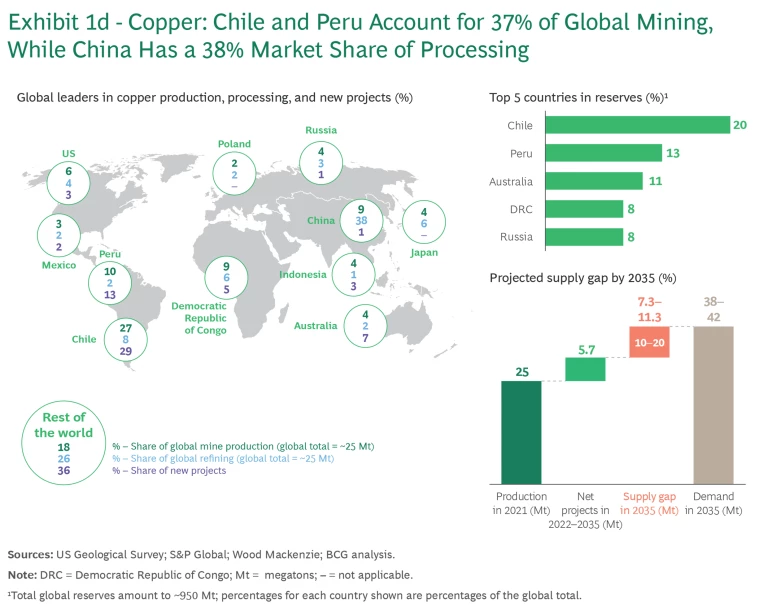

Minerals will be the new oil of the world’s future economy. However, nearly 20% of the total global mineral supply that the world will need by 2035 has yet to be found. (See Exhibit 1.)

So how can the world manage? The answer, we believe, lies in mineral hubs: regional processing centers that consolidate resources and processing capabilities at scale. They can ensure more secure supply lines and drive costs down. The critical partnerships they foster between nations and companies can serve as an important bulwark against geopolitical risks and the global shift toward fragmented, regional supply chains. But the value of mineral hubs goes beyond securing supply. Hubs represent a tremendous economic opportunity for producers and users alike.

In this article, we examine how mineral hubs are reshaping the mineral processing landscape. (See the sidebar “The Future of Process Industries.”) We look at why they are so essential, how they work, and what steps mining companies, manufacturers, and governments need to take to respond to and gain from this emerging force.

The Future of Process Industries

Each article in the series will examine the nature of the new business reality faced by a particular process industry, and how the coming changes will drive technological progress, redefine the industry’s cost structure, and reshape its competitive landscape. The goal: to provide industry leaders with the data and guidance needed to ensure their companies can thrive in the coming years.

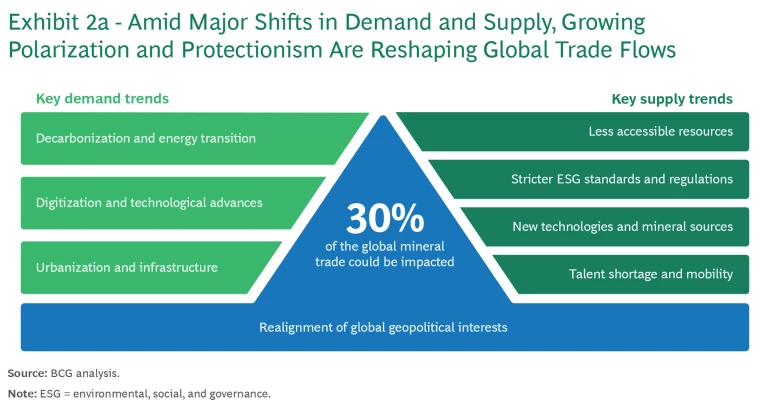

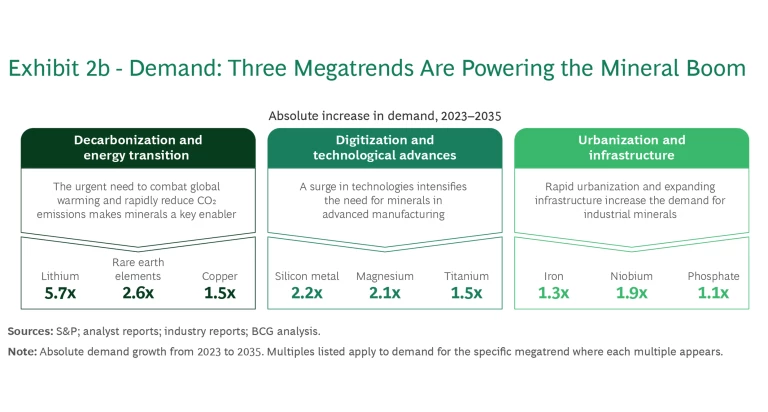

The Big Squeeze from Geology, Policy, and Geopolitics

Renewable energy systems and electric vehicles (EVs)—central components of the energy transition—require several times more minerals than their traditional counterparts. In the race to decarbonize, demand for critical minerals such as lithium, nickel, graphite, cobalt, copper, and rare earth elements (REEs) is likely to increase two- to fivefold over the next decade, reaching $750 billion by 2035. Though more modest in impact, technological advances and urbanization also contribute to the surging imbalance in mineral supply and demand. (See Exhibit 2.)

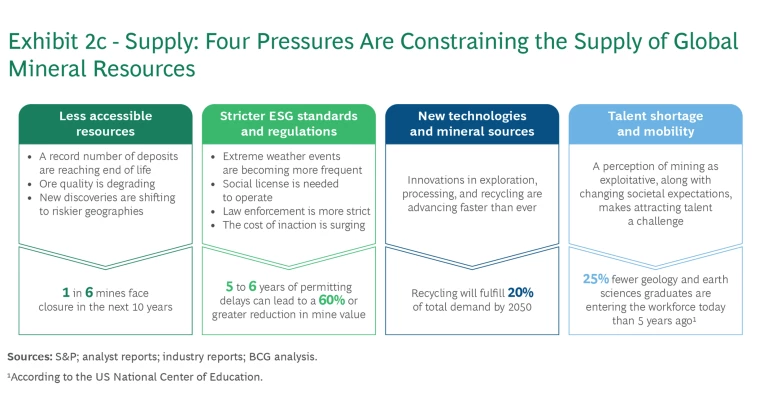

Growing demand coincides with significant geological, operational, and technological constraints, including the depletion of existing mines, a general decline in ore quality, and a shift in new development to riskier regions. Underinvestment in exploration only aggravates these trends. In addition, stricter social and environmental regulations have protracted typical permitting timelines so much that the average time from exploration to first production is now 16 years. Delays can slash a project’s value by over 60%, diminishing its attractiveness to investors and hampering its overall viability.

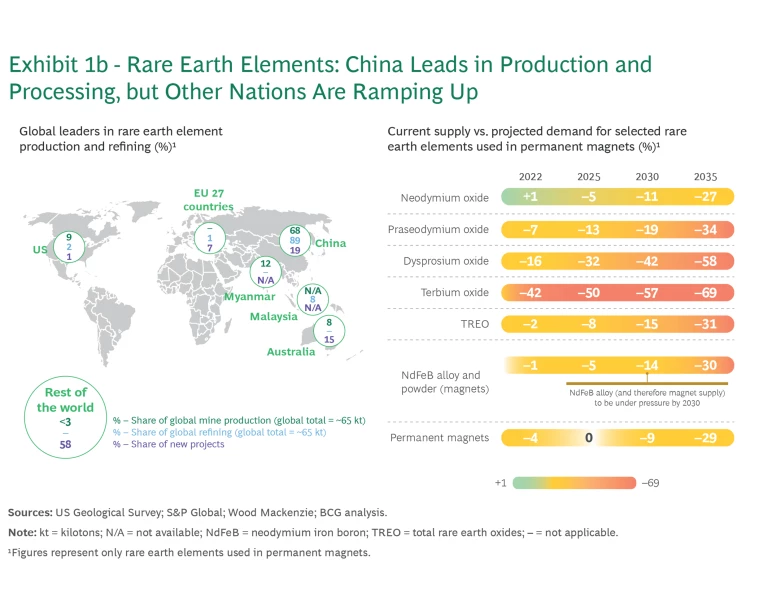

Export restrictions, reshoring initiatives, and the rise of resource nationalism are intensifying the competition for critical minerals and fragmenting global supply chains. China has tightened its grip on REEs, imposing export bans and leveraging partnerships through the BRICS group of nations to expand its influence.

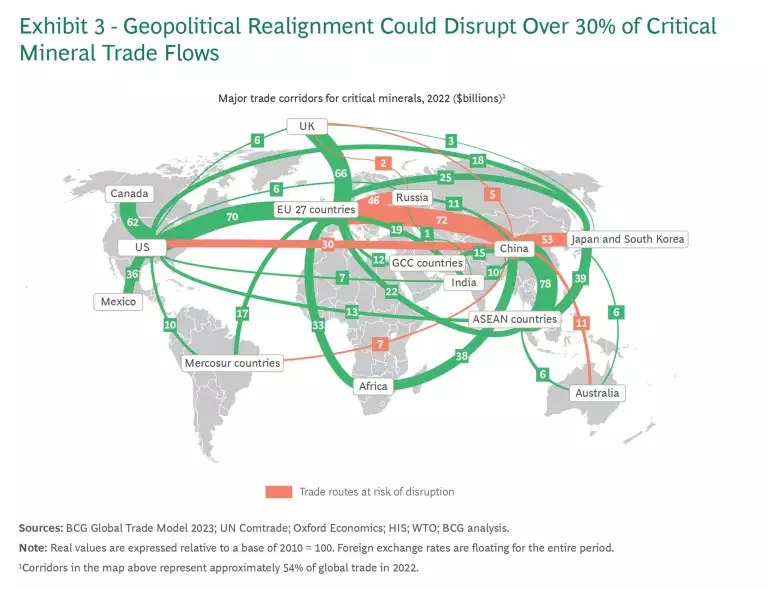

Lately there has been more talk about developing regional supply chains to secure resources and minimize exposure to shocks associated with geopolitical realignment. Such shocks could disrupt around 30% of worldwide mineral trade flows over the next decade, exacerbating supply gaps. Western countries, which rely heavily on mineral imports from resource-rich regions, are particularly at risk. (See Exhibit 3.)

Securing Supply

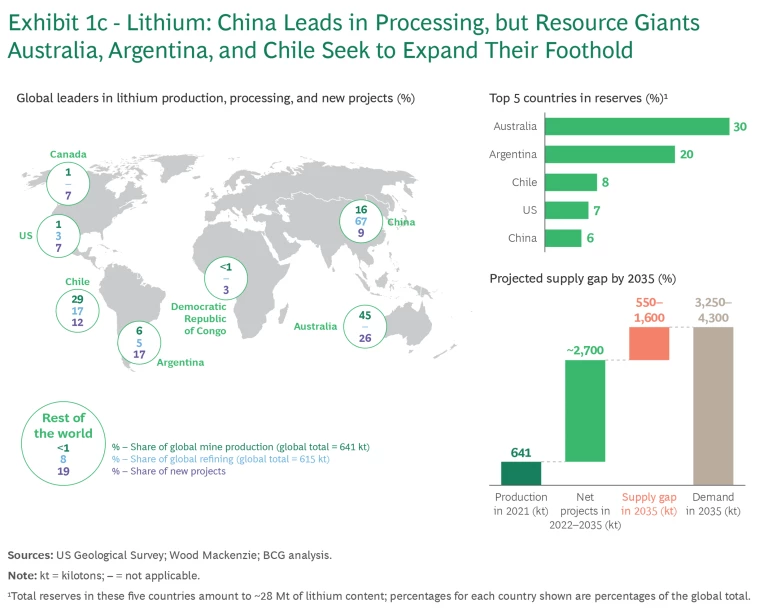

Critical mineral reserves are heavily concentrated in a handful of countries, complicating efforts by consumer nations to reduce their dependence on any one source. Processing is similarly concentrated: China accounts for more than 60% of all mineral processing, and Indonesia dominates the processing of high-pressure acid leach (HPAL) nickel. In response, the US and the EU, for example, are striving to ensure steady and unfettered access to the materials essential for their industries. Initiatives such as the US Inflation Reduction Act and the EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan (which includes the Critical Raw Materials Act) reflect efforts to reshore mineral processing and manufacturing within these countries’ borders and among free trade agreement countries.

As important as these strategies and tactics are, they alone cannot overcome the growing tensions and pressure points that will affect critical mineral supply along the value chain.

Mineral Hubs Are Game Changers

Some countries are leveraging their geographic and resource advantages to establish themselves as pivotal players in the mineral supply chain. Chile, for example, is doing so with copper and lithium. (See the sidebar “Across Regions, Hubs Are on the Rise.”) The growth of these centers marks a paradigm shift in the mineral landscape, driving competition, strengthening supply resilience, and opening new avenues for economic growth and global influence.

Across Regions, Hubs Are on the Rise

The following examples illustrate some of the strategies that countries are employing to capitalize on their natural and commercial advantages.

Morocco. Over the past 20 years, Morocco has built robust downstream industries in sectors such as automotive manufacturing, using locally processed materials to feed the nation’s expanding industrial ecosystems. Its strategic location and industrial expertise are helping transform Morocco into a vital hub for regional and global supply chains. Despite limited critical mineral reserves, the country successfully leveraged the US Free Trade Agreement and the US Inflation Reduction Act to establish itself as a processing hub for critical minerals, bolstering its attractiveness to raw mineral exporters.

Saudi Arabia. Mining and mineral processing are central to the country’s economic diversification plans within its Vision 2030 program. With an estimated $2.5 trillion worth of untapped resources, as well as competitive energy prices and a strategic location on major trade routes, Saudi Arabia has forged partnerships with such majors as Barrick and Mosaic, solidifying its role in global supply chains.

Vietnam. Boasting significant deposits of rare earths (it ranks in the top three globally) and a skilled workforce, Vietnam is swiftly becoming a competitive player in the REE market. Investments by companies such as Lynas Corporation, Toyota Tsusho, and NFC are bolstering the country’s REE refining activity.

Other countries that are involved in refining or other midstream activities include Australia, Chile, Indonesia, South Africa, and Central Asian countries.

Like airport hubs that consolidate passenger and cargo flows before redistributing them, mineral hubs centralize mineral concentrates from various places before processing and selling them to regional or global users. In one location, a hub provides large-scale processing facilities and critical infrastructure to achieve economies of scale and efficiency and keep costs competitive. For example, traditional copper processing facilities generally produce from 25,000 to 100,000 tons of cathode copper each year. A mineral hub can process upward of 500,000 tons, often along with other minerals.

By enabling stable offtake agreements with partners or developers, mineral hubs lock in long-term demand. Beyond its direct benefits, a hub also seeds an integrated ecosystem that fosters innovation , collaboration, and sustainable development.

To this day, large-scale mineral processing hubs are relatively uncommon except in China, which established itself in processing about 40 years ago and quickly surpassed other countries. Although countries such as Australia, Canada, and Indonesia have developed processing capabilities (especially for such minerals as lithium and nickel), China remains the dominant player in the global supply chain.

Indonesia offers a prime example of the hub concept in action. Its ascent as a global nickel-processing hub is not due solely to its holding the world’s largest nickel reserves. Policy adjustments supporting domestic midstream activities, instituted in January 2020, helped accelerate the growth of its processing industry. Indonesia subsequently attracted $21 billion in foreign investment for mining and processing, as well as for strategic partnerships. From 2019 to 2024, the number of smelters in the country increased from 11 to 44, with over 20 more under construction.

The value of Indonesia’s nickel exports grew enormously, from $1 billion in 2015 to $20 billion in 2022, reinforcing the country’s importance in the global EV battery supply chain. Domestically, expansion of the industry has created more than 150,000 jobs, contributing to Indonesia’s economic growth and underscoring its strategic importance in the global critical minerals landscape.

Subscribe to our Industrial Goods E-Alert.

What Does It Take to Become a Successful Mineral Hub?

Although mineral hubs are still relatively new, we’ve identified seven ingredients essential for their success:

- A Stable Mineral Supply. A hub needn’t have access to all of the required resources from domestic sources. Strong partnerships and government-to-government (G2G) agreements with resource-rich countries are keys to securing a reliable and uninterrupted flow of ore and concentrates.

- Entry into Downstream Markets. Such access, which is critical for ensuring stable sales and reducing risk, may be established through significant domestic downstream demand or through bilateral relationships or free trade agreements with larger end markets like the US and the EU. Consistent demand gives decision makers the confidence to commit the necessary capital to investments in processing facilities.

- High Processing Capacity. Large-scale facilities that can process substantial volumes of ores or concentrates enable hubs to maximize efficiency and reduce costs, reinforcing their competitive position.

- An Integrated Infrastructure. Well-developed transportation networks—particularly, major railways, highways, and ports—facilitate the efficient movement of materials and promote growth. Hubs also need adequate land for facilities and future expansion, as well as access to water and available reagents.

- Affordable, Low-Carbon Energy. Mineral processing is energy intensive, so clean, cost-effective energy is critical to ensuring environmental sustainability and long-term competitiveness.

- Access to Low-Cost Capital. Global investors play a vital role in financing large-scale projects. The affordable capital they can attract helps build the hub’s infrastructure and operations to a capacity sufficient to make it a competitive force in the mineral supply chain.

- Government Support. Streamlined regulation, a hospitable business environment, and investments in education, training, and R&D contribute to developing a skilled workforce and stimulating innovation, which, in turn, enhance a hub's competitiveness.

This last point deserves emphasis. Scale and efficiency are critical, but success also depends on strong public-private partnerships. Companies and governments must work together to develop the infrastructure, regulatory frameworks, and workforce necessary to sustain operations. More broadly, such partnerships fuel technological innovation and help attract the investment needed for long-term growth and global competitiveness.

Mineral Hubs and Their Implications for Stakeholders

Mineral hubs are already beginning to reshape the global supply chain for critical minerals. How should major producing nations, mining companies, and end users—countries and manufacturers alike—factor them into their strategy?

Resource-Rich Countries. Countries with ambitions to establish themselves as a force in mineral processing must carefully assess their competitive positioning with respect to the key enablers that we described earlier. For example, how can they obtain the substantial capital needed to build infrastructure and processing facilities? How well situated are they to attract international investors and manufacturers? Even the largest producing countries can’t rely solely on their domestic assets and capabilities. Partnerships, whether public, private, or both, are essential to efforts to move swiftly and gain a competitive edge in the global market.

Government plays a pivotal role by creating an enabling environment: establishing clear regulatory frameworks, streamlining permitting processes, and offering targeted subsidies to draw private sector investment. For example, by fast-tracking approvals for lithium and REE projects, Australia has attracted global investment and strengthened its position in the critical minerals supply chain. Saudi Arabia, in keeping with its Vision 2030 strategy, has introduced various enabling mechanisms to help spawn partnerships with global firms and accelerate investment. Collaboration between the public and private sectors, along with international partnerships and G2G agreements, are fundamental to ensuring that hubs scale efficiently, adopt new technologies , and meet global sustainability standards.

For countries where a standalone hub may be unfeasible, forging strategic partnerships with emerging hubs is the next-best option. These associations provide resource-rich countries with stable mineral offtakes, while allowing them to optimize their long-term investment in and capability planning for exploration and development.

Global Mining Companies. In an era of growing resource nationalism and regionalism, global mining companies need to be able to engage with multiple hubs in low-cost, geopolitically stable regions. In this way, they can preserve their global reach, ensure a steady feedstock of critical minerals, and minimize the risk of market-access distortions such as those caused by import bans.

Accordingly, such companies must strengthen their ability to identify and anticipate policies that may affect their business, and to assess how likely those policies are to be implemented. Scenario planning needs to be an integral part of strategic planning. When possible, companies should also work with governments to explore innovative investment packages and make policymakers aware of the opportunities they offer. Strategic decisions regarding where and how to invest—whether through joint ventures or strategic alliances—are also crucial to ensuring operational resilience.

Junior Mining Companies. Given the financing constraints and project development challenges that juniors commonly face, mineral hubs represent a welcome opportunity for them. Hubs enable juniors to bring projects online more efficiently, while mitigating risks through stable offtake agreements that enhance their ventures’ viability and sustainability. By integrating into these broader ecosystems, smaller mining companies can partner with hub operators and downstream companies to gain access to capital (including through financing agreements such as streaming) and accelerate project timelines.

Major Manufacturers and Downstream Users. In an increasingly fragmented global market, companies, particularly in the US and EU, have an urgent need to reevaluate their sourcing strategies. But securing long-term access to critical minerals—which is imperative in the EV, electronics, and renewable energy sectors—does not mean require establishing domestic processing hubs. Manufacturers and end users simply need access to a cost-effective mineral supply, which they can obtain by actively engaging with mineral hubs. On the macro level, the governments of consumer nations can help build long-term supply security for their home industries; specifically, they can strengthen bilateral critical mineral trade relationships and build global, multilateral alliances to provide the investment stability essential for hubs to flourish over the long term. In this way, governments can support their industries’ enduring competitiveness.

Mineral hubs offer a solution to the mineral supply gap that threatens not only the energy transition but also the future of advanced industry in general. Ultimately, the success of these hubs and of the stakeholders that depend on them will rest on the strength of partnerships. Whether between nations, between corporations, or between industries, collaboration will be key to building resilient supply chains, unlocking investment, and ensuring access to the resources necessary for a sustainable future. In today’s interconnected world, partnerships are not merely a useful strategy, but the cornerstone of global competitiveness in mineral processing.

Still, the top priority today is to take swift, decisive action. Competition is intensifying as supply pressures and supply chain issues mount—and the window will not remain open long. Stakeholders that seize opportunity now may be well on their way to commanding a leading position in the mineral hub field.