In most ways that matter, large companies benefit from the competitive advantages that come with global reach—things like economies of scale, more resources, and access to markets and talent. In different geographic markets, however, where customer relationships and customization for local preferences are important success factors, the organizational size and centralization that are normally economic assets can put multinational companies at a disadvantage in competition with more nimble, local players.

In several emerging markets where multinationals compete with local counterparts, the local companies outperform the global ones. A BCG study that looked at company growth rates and margins in five emerging countries from 2017 to 2021 found that the local players achieved 3% to 4% faster annual growth and had EBITDA margins 200–300 basis points higher than the multinationals.

Many smaller companies have achieved this home-field advantage in recent years due to the acceleration of three disruptive forces: the fracturing of geopolitical consensus, the onward march of digitization, and the growing importance of customer experience . Armed with available technology, increasingly sophisticated local companies are able to succeed against multinationals by meeting the changing demands of local customers with speed, responsiveness, and innovation .

To compete successfully, global companies need to replace the one-size-fits-all approach that has typically worked well in the past with one that balances global scale and local customization to drive market penetration and loyalty. The approach is called

fractal innovation

—which in business means creating adaptable, scalable structures inspired by nature’s patterns, like the way snowflakes under a microscope repeat smaller versions of themselves.

Fractal Innovation Tackles Key Challenges

Multinational companies face two main innovation challenges related to local market presence and the scope of local opportunities.

Multinationals have a limited understanding of local market and customers.

Effective innovation requires having a deep understanding of what the customer wants and needs. But in local markets, large companies often struggle to gather this information due to limited market presence, hindering their ability to capture the subtle insights necessary for innovation that resonates with customer preferences.

The opportunity size does not warrant big investments.

For many companies, the expected sales potential in smaller markets does not justify the high costs of traditional R&D investment. This creates a tricky situation where the market remains underserved because companies are hesitant to invest; yet without investment, the true potential of the market cannot be unlocked.

Fractal innovation is gaining attention as a way for large companies to address these challenges by decentralizing R&D decision making without diluting the synergies and economies of scale that are core advantages of the multinational enterprise model. Several companies are demonstrating the potential of this approach in emerging markets by setting up local innovation centers and deploying regional R&D teams. For instance, some global manufacturing and technology companies have established R&D or innovation centers in India and Southeast Asia to develop technologies for the local market.

Subscribe to receive BCG insights on the most pressing issues facing international business.

Some business leaders might wonder about the feasibility of implementing localized, fractal innovation. While the model appears to require a complicated balancing act, companies that plan their strategy carefully can travel this path to greater R&D agility in a manageable, step-by-step approach.

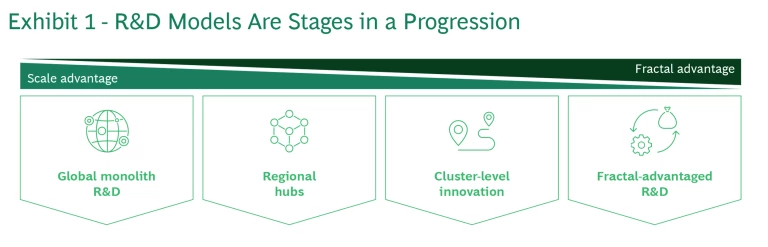

The Journey to Fractal Innovation Is a Continuum

The road from a traditional, centralized innovation structure to distributed, localized, fully fractal innovation occurs in stages. We have identified four models that identify the stages, each with considerations and trade-offs, as a way forward for companies considering the benefits of local-market R&D customization. While an “all-fractal” strategy is certainly not the right solution for all companies, many global organizations stand to benefit by adopting selectively from the models or by deploying elements of the models gradually to determine what fits best before diving deeper. (See Exhibit 1.)

Global Monolith R&D.

This is the traditional multinational approach to innovation. Centralized and efficient, this model leverages economies of scale but often lacks the flexibility and local market insight needed to respond to rapid changes in consumer preferences.

Regional Hubs.

These semi-centralized units offer a balance between global efficiency and local responsiveness. While they allow for some degree of market-specific innovation, they may still be too removed from the granular needs of local consumers.

Cluster-Level Innovation.

Focusing on clusters of countries or customer segments, this model enhances a company’s ability to tailor products and services to local markets. However, it risks increasing complexity and diluting the strategic focus.

Fractal-Advantaged R&D.

The epitome of localization and agility, this model maximizes responsiveness to market needs. The trade-off here involves managing the complexity and coordination challenges inherent in a highly decentralized structure.

As companies move along this continuum, they become better equipped to respond to rapid changes in local consumer needs and market conditions, providing tailored solutions efficiently and effectively. Fractal-advantaged R&D represents the mature state of this evolution, where the flexibility and responsiveness of the R&D structure are maximized.

How Should a Company Decide Which Model to Deploy?

To reap optimal benefits from innovation, it is important to select a model that fits the business and its customer-product context, based on identifiable success factors and market triggers.

- A traditional, monolithic R&D model is favorable when margin pools are highly concentrated in select markets and there are large one-time platform development or innovation costs.

- Companies should choose the regional hub model when the focus is on markets with critical mass or where product standards enforce homogeneity.

- A cluster-level model is appropriate when business growth is contingent on a broad base of markets and when customer needs vary across each market, especially if there are lower one-time platform development costs and easy adaptation is possible due to modular design.

- A full, fractal-advantaged R&D model is relevant for truly global businesses with a solution-oriented mindset that are aiming to solve market-specific customer needs.

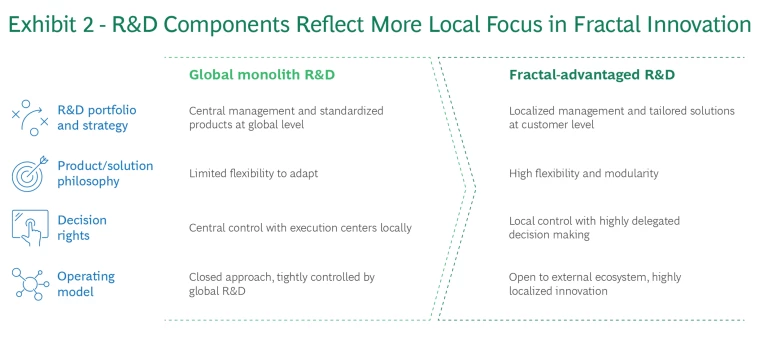

A typical R&D model comprises several components. Key among these are R&D portfolio and strategy, product and solution philosophy, decision rights, and funding and operating model. Large companies working to develop a fractal-advantaged R&D structure must actively manage and coordinate all of them. (See Exhibit 2.)

The transition to a fractal model requires a strategic shift that increases local responsiveness at every stage. By incrementally allowing more localized decision making and adapting the product development process to be more modular and customer-focused, companies can tailor their innovations to be relevant and competitive in each local market they serve.

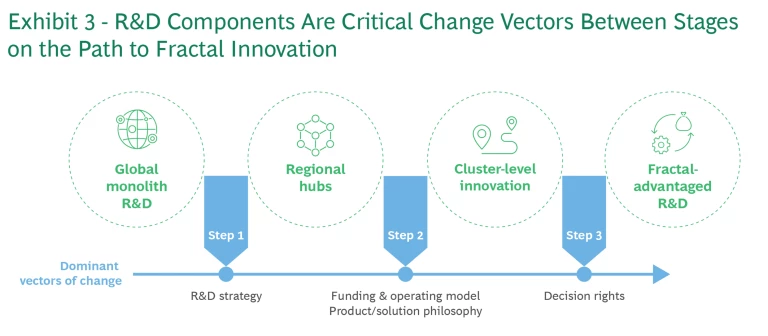

Three Steps to Successful Fractalization

Transitioning from one innovation model to another requires making changes across the different components, but for each transition one or more of the core model components is a dominant vector of change. (See Exhibit 3.)

Step 1. Global Monolith R&D Model to Regional Hubs

The vector of change in this first major transition is a reshaping of the organization’s overall R&D portfolio strategy—from one where products are designed with little consideration for local nuances, flexibility is limited, and decisions are centrally controlled to an approach that enables regional execution capabilities and development of local market intelligence. The R&D portfolio begins to account for the average needs of three to five hubs, each with a sizeable demand base. Regional hubs have greater autonomy in decision making and assigning targeted mandates. Product platforms remain integrated and fixed but with the possibility of some minor adaptations for large volume bases. Decisions and operations are regionally controlled, although local teams may still function as low-cost execution centers.

Step 2. Regional Hubs to Cluster-Level Innovation

This transition requires a change in both the product and solution philosophy and the funding and operating model. The starting point is establishing mechanisms for seamless information flow across hubs, complemented by higher modularity in the design of products and solutions. The transition also requires low-frills, smaller scale platforms with customizable sub-modules. Local teams gain decision rights over portfolios, project selection, budgeting, and execution, and the operating model is more open, with greater inputs from market-facing teams, such as sales and customer service. Further shifts focus on three priority areas: funding (budgets for target markets are centrally-approved); expertise (innovation centers are enhanced with specialized centers of excellence); and talent availability (talent shortages are addressed through mobility, focused local hiring, and comprehensive upskilling).

Step 3. Cluster-Level Innovation to Fractal R&D Model

In the transition to a fully fractal R&D model, decision rights are the most important change vector. In this stage, decision making is highly delegated across funding, portfolio selection, and execution, with “solution architects” or product owners having substantial autonomy to drive customer-centric innovation. To be fully fractal, companies must further refine their product philosophy by incorporating software or API integration to enable tailored responses to individual customers or customer segments. The product structure is highly modular, facilitating the interplay of hardware, software, and API microservices for rapid and granular local adaptation. In a fractal model, the operating model is fully open, supporting highly localized innovation, local innovator partnerships, and a vibrant ecosystem that encourages collaboration and rapid iteration.

Each step in this transformation is its own journey and cannot be rushed. Like with any process of change, it is crucial to establish bold aspirations and initiate lighthouse projects to test the model and demonstrate its effectiveness. Companies must also invest in new technical capabilities from the outset of the transformation to facilitate a smooth transition.

Global companies today operate in an increasingly fragmented and complex world. To achieve new growth they must expand into more markets, but they are finding that the existing local companies in those markets are more nimble and savvy than ever. To compete successfully, multinationals need a new approach to innovation.

Future-ready industrial companies are meeting this challenge by moving from a global to a regional, fractal innovation approach with adaptive, modular design capabilities that facilitate local customization. Fractal innovation enables companies to be more responsive to customer needs while still leveraging their global scale. Global companies that embrace fractal innovation will not merely adapt to specific market conditions but will set the pace for competition in their sectors.