Acquirers often fail to realize the full value of a merger because they tend to view integration of the target’s business functions through the narrow lens of cost synergies. This isn’t surprising—cost synergies are not only relatively easy to measure and manage but also the main rationale for most mergers and acquisitions (M&A). According to a recent BCG study of more than 4,000 deals—believed to be the largest of its kind—more than 71 percent of acquisitions in 2006 were driven by a quest for greater economies of scale. To unlock the full long-term potential of a merger, however, acquirers need to think laterally and treat integration not as a functional exercise but as a strategic opportunity to reformulate each function’s role so that each one plays a full and complementary part in optimizing the combined entity’s long-term growth.

This report, the second in our series on post-merger integration (PMI), explores the key issues that need to be taken into account when acquirers integrate five core functions: information technology (IT), research and development (R&D), procurement, production and networks, and sales and marketing.

As in the first report in our series— Powering Up for PMI: Making the Right Strategic Choices —our goal is not to provide a technical guide but to highlight potential strategic opportunities and pitfalls. To set the scene, we summarize the main issues raised in our first report. We then briefly discuss the common challenges and opportunities that every function faces before examining, in more detail, the strategic issues encountered by the five core functions.

The Story So Far

Our previous report highlighted three steps that should be taken before a deal is closed or, ideally, before a bid is made.

Establish the strategic pulse of the PMI. Different types of mergers require different speeds and styles. A consolidation merger, for example, should be rapid and top-down, whereas a growth merger requires a more gradual, collaborative approach. In reality, most deals involve a combination of cost and revenue synergies in different functions, business units, and geographies, so a segmented approach will be needed—there isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution.

Prepare to hit the ground running. Preclosure fact-finding and planning is essential to start releasing synergies on day one of the PMI. This requires establishing a clean team to analyze potential synergies and to draw up a provisional integration plan in a secure, confidential environment before the deal is closed. Equally important is creating a dedicated PMI implementation team—guided by a powerful project management office—to translate the clean team’s synergy targets into stretch yet realistic goals for each business unit through an iterative top-down, bottom-up process.

Think hard about the soft issues. An acquisition inevitably creates uncertainty among the acquirer’s and the target’s staff, and these anxieties have to be proactively managed the moment a deal is announced. A well-considered communications plan—rooted in regular, fact-based surveys of the staffs’ hopes and fears—is a prerequisite for success. A systematic understanding of the cultural differences between the two companies also is essential.

The Challenges and Opportunities That All Functions Face

Although different functions face different issues during PMI, there are several common challenges and opportunities.

The Chance to Reconfigure the Operating Model. A merger not only creates an appetite for change but also brings together different ways of thinking and operating—often sparking novel ideas to take the combined business to a new level. In manufacturing, for example, there may be opportunities for worldwide sourcing or for creating a new network of global, regional, and local production sites that leverages a company’s newfound scale and improves delivery speed. Establishing a more strategic role for procurement—including integrating it into the decision-making processes of R&D and other functions—is another option that can release greater-than-expected synergies. Other possibilities include introducing cross-functional teams to identify hidden synergies and rolling out globally benchmarked best practices. However, unless these opportunities are seized at the start of PMI—when the willingness to change is greatest—acquirers are unlikely to make much headway.

The Risk of Staff Defections. Although a certain percentage of staff will always leave during a merger, particular attention should be paid to retaining star performers in the most critical functions. In the engineering and pharmaceutical industries, for example, R&D staff are likely to be a top priority, whereas IT personnel will be high on the list in banking, insurance, and Web-based businesses. In virtually all sectors, the risk of defections among sales staff is especially high because these employees tend to be out in the field, beyond a company’s immediate sphere of influence and normal corporate communications channels.

One step that is essential to retaining top talent is to reach out to key individuals as soon as a deal is announced in order to assure them of their future in the combined

The Need to Look Beyond Cost Synergies. Pressure to deliver synergies as rapidly as possible can lead to a blinkered fixation on cost reduction at the expense of revenue synergies. Expecting a smaller, combined sales force to sell a larger number of products without appropriate training and incentives is one example. In fact, it can sometimes be more productive in the long run to incur higher costs at the start of PMI—for example, by investing in a redesign of vital products and common components. As with every facet of PMI, these and other possibilities must be carefully evaluated long before the deal is complete. Moreover, all assessments must include a detailed evaluation of potential revenue synergies. Cost synergies are expected, but the true strategic measure of any acquisition is its ability to generate long-term growth and value. Moreover, the growth story is especially important for winning the hearts and minds of staff. Growth—not cost savings—is the source of sustainable, long-term success.

IT: The Key to Unlocking Synergies

IT often slips down the list of priorities in PMI, especially in industries such as engineering and consumer goods, in which IT is not considered a key competitive advantage. Maybe it’s the “geek factor” or an assumption that IT is fundamentally a technical “plug and play” issue. Whatever the reasons, it can be a costly mistake to ignore IT.

Apart from the fact that IT can generate about 15 to 20 percent of total synergies—rising to as high as 30 percent in information-intensive industries, such as banking and retail—it plays a critical role in enabling other parts of the business to deliver synergies. In banking, for example, more than 50 percent of all synergies across all functions are dependent on IT. Let it fall off the radar and the core advantages of a merger can easily vanish.

The question, of course, is, What is the best way forward? As with so many aspects of PMI, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. Different types of M&A—from mergers of giants to tuck-ins and cross-border transactions—present different challenges. So too do different industries. Nevertheless, there are several prerequisites for success that apply across all M&A configurations and industries. These include ensuring that the basics are in place, identifying clusters and nuggets, implementing as rapidly as possible, and developing a world-class IT integration team.

Ensuring That the Basics Are in Place. In the heat of PMI, it’s easy to overlook ostensibly mundane yet essential elements of IT needed to “keep the lights on” when a deal goes live. To avoid this pitfall, there must be a plan in place to ensure that basic connectivity and appropriate security are available and functioning on day one. Having IT up and running at this critical juncture will also send a signal to both companies that the integration has started and that IT is playing its part. Particular attention should be paid to systems that are critical for business continuity, such as the branch-network information system in a retail bank. It is also essential that the key personnel associated with these systems—in both organizations—be identified and retained. With the growing demand for top IT talent, headhunters will pounce as soon as they sniff the inevitable uncertainty of a merger. In addition, an inventory of ongoing IT investments and vendor relationships should be taken and reviewed to determine which investments and contracts to sustain, amend, or terminate.

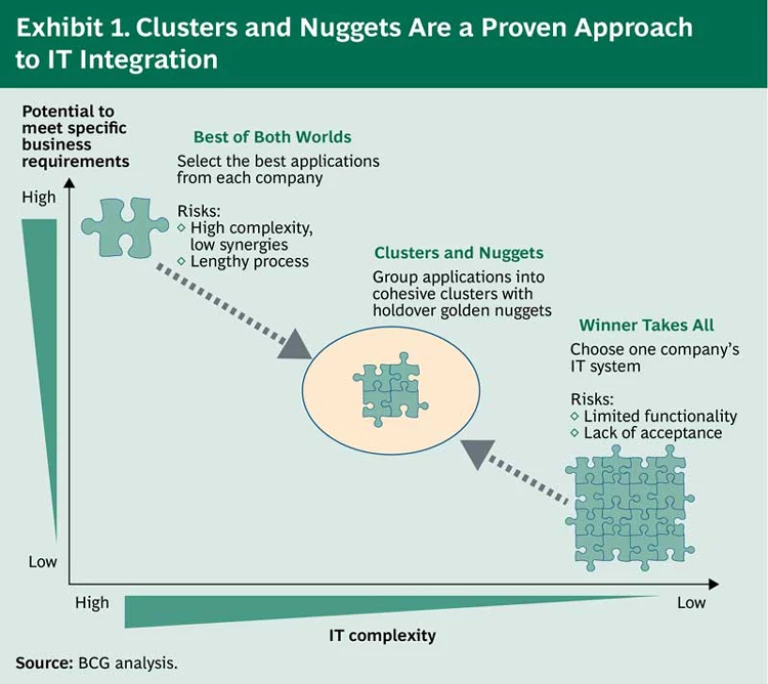

Identifying Clusters and Nuggets. IT plays a pivotal role in delivering synergies across a combined entity’s operations. And the pressure from investors for these gains to be realized rapidly can be intense. Therefore, it is important not to attempt to create a totally new systems landscape. (See Exhibit 1.)

One option is to cherry pick the best applications from each company—using operational and financial criteria. This best of both worlds approach, however, can create a patchwork of applications that run on different technical platforms, require new links, and increase the risk of failure. It can also be extremely time consuming. In a recent banking megamerger, for example, the acquirer had to choose among more than 3,000 applications.

Another option is to select one company’s system landscape over the other’s. Although this winner takes all approach might be the best and quickest solution in small, tuck-in acquisitions, the choice is less clear-cut in large-scale mergers and will inevitably be tainted by political considerations. The losers in this often elongated and confrontational tussle will feel they have lost not only functionality but the battle as well. As a result, the losers will often develop an “us versus them” mentality. Also, they will likely require extensive training to bring them up to speed with the winner’s system.

In these situations, the most effective and pragmatic solution is to seek commonalities through clustering. This involves IT teams grouping all the applications from both companies into clusters on the basis of the applications’ technical ability to be isolated from surrounding systems, including their architecture, age, flexibility, and business alignment. It’s essential that the managers of each business validate the clusters to ensure they reflect each unit’s functional needs. For a portfolio of around 2,000 applications, there will typically be about 40 to 50 clusters.

Standardized selection criteria should be used to choose among these clusters and ensure transparency and objectivity. Although various criteria will enter the equation—such as business functionality and the flexibility and durability of each cluster’s architecture—the two most important criteria will be speed of implementation and minimization of the impact of any changes on customers (even if this means selecting a suboptimal cluster). Personnel considerations are central because of the need to retain the individuals key to maintaining the chosen clusters.

Inevitably, there will be a handful of competitively critical applications that are not part of the selected clusters, such as state-of-the-art systems for measuring and controlling counterparty risks or specific reporting services for corporate or institutional customers. These golden nuggets—especially customer-specific nuggets—must be identified, retained, and consolidated into the selected platform.

Clustering does not always produce the optimum long-term IT outcome—a totally new system might be required farther down the road—but it does provide a stable platform for rapidly maximizing the benefits of the two companies’ systems. Alternatives can be explored at a later stage.

Implementing as Rapidly as Possible. As BCG research and client work have consistently shown, companies must seize the momentum of a PMI early and start to integrate the IT systems within the first few months—with clear timelines and milestones for completing the task. Otherwise, they are likely to find themselves in the same spot several years later—with a fragmented and redundant systems landscape. The corporate “will to change” is short lived. Customers also want IT issues resolved swiftly, with minimum disruption to their day-to-day business with the organization.

Rapid implementation requires accepting a tradeoff between perfection and speed. A system that is 80 percent right today is infinitely preferable to one that could be 100 percent right in five years (by which time it will probably be outdated). Speed also forces clear decisions—and demands acceptance that there will be winners and losers. But to stay on track, companies need disciplined planning and implementation processes—including systems to monitor progress in realizing synergies. This is especially important in IT because the integration process tends to have long lead times and is vulnerable to PMI fatigue.

Developing a World-Class IT Integration Team. The most successful serial acquirers establish and nurture dedicated IT-integration teams. These teams are involved from the outset of the M&A process and have tried and tested packages of tools—which include well-documented, corporatewide standards for IT architecture and application portfolios—as well as established processes for implementing them (such as creating appropriate task forces). These best practice benchmarks are not rigidly applied but are instead tailored to the individual circumstances of the combined company. To ensure that the solution meets the business’s needs, the IT integration team should include members of various business units—not just IT—and work closely with all business units across the company.

R&D: Tread Softly

Integrating R&D processes and pro-cedures—such as stage-gate decision points and criteria for product inno-vations—isn’t easy, but it’s even tougher to get the “softer” people issues right. And getting the people issues right is especially critical to the success of a merger in knowledge-intensive industries such as biopharmaceuticals, e-commerce, and IT.

The main difficulty is that R&D’s greatest asset—its key personnel, including their knowledge and expertise—can walk out the door as soon as an acquisition is announced. In fact, many R&D employees often do. On average, companies lose at least 10 percent of their R&D talent base and, in some cases, the percentage can be much higher.

Moreover, even companies that manage to retain key R&D staff have to contend with the challenge of creating a unified team out of a potentially volatile cocktail of egos and divergent scientific viewpoints. In R&D, the bonds and beliefs of “competing” teams are probably more entrenched and more jealously guarded than in any other part of an organization.

What’s the best way to mix and match these capabilities? Should the acquirer absorb the target’s R&D into its existing operations? Or should it use PMI as a springboard for creating a new R&D model for innovation? Or is it wiser to keep the two R&D teams separate?

To deal with these and other R&D-related issues in PMI, four major steps need to be taken: identify the “golden goose,” plan for tomorrow’s products—while supporting today’s, decide whether to integrate or isolate, and retain and close sites sensitively.

Identify the “golden goose.” The target’s core competitive strength in R&D—intellectual property, project pipeline, technology, or employees’ expertise—will determine the strategic direction and speed of an integration. If the target’s key asset is intellectual property, people issues will be less critical and integration can occur relatively rapidly. Conversely, if the target’s core assets are closely linked to employees’ knowledge and expertise—such as the project pipeline—integration must be handled more sensitively.

The difficulty is that the information needed to identify a target’s core asset (golden goose) is rarely publicly available, owing to the commercial sensitivity of R&D. The most effective way to overcome this hurdle is to establish a clean team to evaluate the target’s strengths before a deal is

Plan for tomorrow’s products—while supporting today’s. To determine which R&D projects to support and which to discontinue—and how to manage and allocate resources during the transition—acquirers need to conduct detailed analyses of the industry landscape, focusing on the markets that offer the greatest long-term value-creation potential relative to their capabilities.

In industries in which products tend to have long life spans—such as the automotive and power-generation industries—acquirers should factor in significant human and financial resources to support legacy products. Failure to do so will undermine the market’s confidence in the combined company’s ability to service both current and next-generation products. Acquirers might not always have the freedom to discontinue lines and migrate customers to new products. In the software sector, for example, customers can be very resistant to switching platforms, especially when key business systems are involved.

An often overlooked opportunity is retaining a stake in the upside of any projects that are sold or spun off because they are either noncore projects or too small to warrant continued support. Several big newly merged pharmaceutical companies have gone down this “spin-out” road, creating standalone biotech companies that have been spun out of development teams. Spin-outs like these can offer outside investors a compelling proposition—including an established development team, well-developed intellectual property, and the commercial support and capabilities of the parent company.

Decide whether to integrate or isolate. Some acquirers manage the target’s R&D independently, usually to protect the unit’s dynamism and agility. In these situations, it is often valuable for the target’s and acquirer’s R&D units to share back-office systems and be governed by common decision-making processes so that the unit feels it is part of the organization.

When two companies’ R&D teams are integrated, systems and processes should be introduced to facilitate sharing and cross-fertilizing knowledge and expertise—for example, by rotating staff between teams. In mergers in the automotive industry, for example, staff from the more technologically sophisticated company are often temporarily transferred to the other company to introduce best practices. Because of employees’ sensitivities, this process should be carried out gradually.

Another avenue for integration is to create cross-functional, multidisciplinary teams to explore ways that the combined entity’s R&D capability can exploit technical and scientific synergies. In all cases, the emphasis should be on creating a two-way flow of knowledge and information. Each entity can invariably learn from the other. In the pharmaceutical industry, for example, a merger of a small biotech firm and a large pharmaceutical company provides the biotech firm with global development capabilities and an extensive library of compounds, while the pharmaceutical company gains specialist knowledge and expertise in fields such as antibody production.

Retain and close sites sensitively. Companies often underestimate the emotional attachment that both employees and (especially) local communities have to R&D sites. Having an R&D site in a community does more than just provide high-paying jobs for highly skilled employees. It is often also a symbol of creative renewal. Consequently, R&D site closures must be handled with extreme sensitivity and supported by a well-crafted public-relations and communications plan.

If the target company’s R&D sites are to be retained, it is essential to signal this news clearly and quickly. For example, in many biotech mergers, the potential addition of what will be a new R&D site for the acquiring company—and access to new talent and a new scientific network in a new location—is often a key driver for the deal. In these circumstances, quickly signaling the intent to retain a target’s R&D site—perhaps through the announcement of a respected senior R&D leader as the site head—can go a long way toward allaying fears and forestalling the loss of R&D talent that might otherwise result. More generally, such good news can create a positive, forward-looking spirit among many stakeholders.

Procurement: A New Strategic Role?

As the purchase of goods and services often represents more than half of a company’s total costs, it’s not surprising that procurement usually delivers the lion’s share of total synergies of a merger, with savings ranging from 5 percent to as high as 25 percent. Yet these potential gains—and the opportunity to generate much larger savings in the long run—are rarely fully exploited.

Part of the problem is that acquirers tend to underestimate potential savings. This is largely due to a lack of rigorous premerger analysis and planning. But it is also a function of human nature. Too often, vested interests—including the desire to preserve the status quo—lead to unnecessarily cautious targets.

The more significant stumbling block, however, is the widespread tendency to view procurement simply as a numbers game. Although larger purchasing volumes will usually enable the combined entity to negotiate lower prices with its suppliers, one of the biggest advantages of M&A, from a procurement perspective, is the opportunity to rethink how to buy and from whom, not just how much to purchase and what price to pay.

Approached properly, this rethinking can unlock the true strategic value of procurement—far beyond scale—and radically improve the combined entity’s long-term cost structure and flexibility.

To achieve these benefits and ensure immediate optimization of purchasing synergies from a merger, acquirers need to attack procurement PMI on two fronts simultaneously—from both a cost-reduction and an organizational perspective. This involves four key steps: understanding the potential synergies in depth, challenging long-established supplier relationships and assumptions, questioning products’ technical specifications, and repositioning procurement at the heart of the company’s strategic decision-making processes.

Understanding the Potential Synergies in Depth. As we discussed in our first report in this series, if the lion’s share of synergies is not delivered 12 to 24 months after a deal is signed, the merger is unlikely to succeed. It is therefore essential to develop an in-depth understanding of potential synergies, supported by stretch targets, before a deal is complete. Deploying a clean team is the best way to do this.

With indirect costs, there is often a huge array of ostensibly minor cost-reduction opportunities that rapidly add up to major savings—sometimes in excess of 25 percent of these costs—although the political sensitivities of tackling these cuts should not be underestimated. For example, who is entitled to a corporate cell phone or a company car? And who should be entitled to travel business class and when? Direct material costs can generate even more attractive synergies, depending on the degree of overlap between the two companies’ products.

Releasing these synergies requires focusing on three areas: commercial relationships with suppliers, technical specifications of products, and internal processes and organization.

Challenging Long-Established Supplier Relationships and Assumptions. The acquirer’s supplier model should never be taken as the de facto solution. Every aspect of the acquirer’s relationship with its suppliers should be rigorously challenged and contrasted with the target’s strategy and tactics, as well as with industry best practices. What is the optimal number of suppliers? And are there opportunities to work with preferred suppliers, possibly on a design-to-cost basis?

Involving preferred suppliers in the design and development of products—so that they share their know-how and expertise—is often an excellent way to reduce costs and achieve favorable terms and conditions in the long run. Global sourcing options—including procurement alliances—should also be investigated. Recently, a North American acquirer reduced its purchasing costs by nearly 10 percent by switching from its local-sourcing strategy to the global approach of its smaller target.

Questioning Products’ Technical Specifications. Hard questions need to be asked about the company’s products. Do any nonstandardized components or materials add value? Can design complexity be reduced without compromising the product’s integrity? Can the overlaps between the two companies’ products be increased by introducing common components? And should these components be made or bought? When there is a common industry standard, it is usually preferable to outsource the component’s production. When this is not feasible, design-to-cost opportunities for the next generation of products should be explored as part of the merger process. Although redesigning products to introduce greater standardization can increase costs in the short term, the long-term savings can be significant.

In all cases—from outsourcing to design-to-cost possibilities—it is essential to consider the options in close cooperation with the heads of other functions because any decision will inevitably have an impact across internal processes.

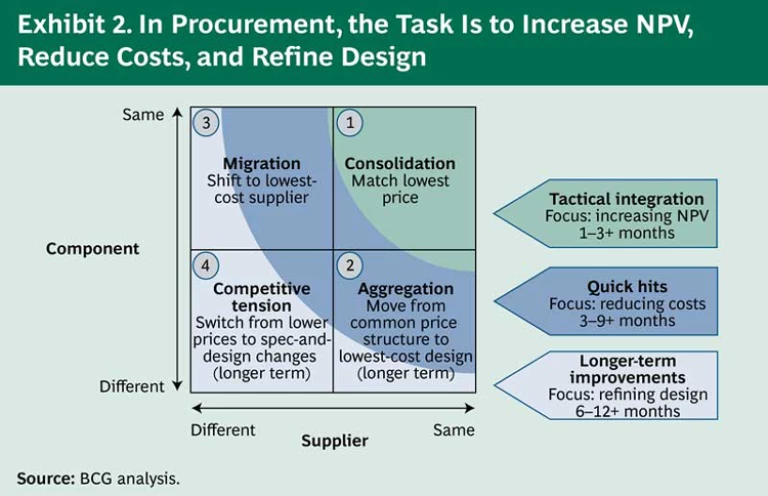

It is equally important to have a prioritized plan for improving the procurement of each component of a product, depending on whether the component is standardized or nonstandardized and whether it is sourced from one supplier or several. The timing and measures of success will vary, but generally the first priority should be tactical integration to increase net present value (NPV), followed by “quick hits” to reduce costs, and then longer-term design improvements. (See Exhibit 2.) Tactical integration of a standardized component produced by a single supplier, for example, should be sought within the first one to three months of integration.

Repositioning Procurement at the Heart of the Company’s Strategic Decision-Making Processes. The procurement organizations of both companies—including the people, processes, tools, and technologies—should be benchmarked against best practices, both within the industry and across other industries, to identify the optimum configuration. For example, can processes be sharpened by introducing a Six Sigma–style approach—including more rigorous procurement planning to avoid emergency purchases? And what systems can be introduced to improve insights into suppliers’ economics in order to secure better prices and purchase agreements?

Opportunities to involve procurement in the early stages of a product’s design and development—when the largest part of a product’s final cost is determined—should also be explored.

More generally, a road map should be developed to integrate procurement—as part of a cross-functional team—into the decision-making processes of all key functions. All decisions—from engineering to marketing—should be viewed from the perspective of minimizing total costs, and procurement costs are a vital part of this equation. These cost-reduction assessments can often stimulate highly creative solutions and liberate resources for investments in future breakthroughs.

Any steps to take procurement to a higher level will, of course, involve organizational change, so securing top-level buy-in will be critical. New talent will also have to be recruited to move forward.

Production and Networks: Getting the Design Principles Right

Consolidating production plants can reduce manufacturing costs by as much as 20 percent, but the decision to maintain or close particular plants is rarely driven by cost considerations alone. A variety of factors needs to be taken into account, such as the types of products manufactured and outsourcing opportunities, legal constraints and commercial risks within individual countries (including the likelihood of labor unrest).

The first and most critical step to navigate through this maze of issues is to decide the optimum design for the manufacturing network. Should it be a single site or a network of global, regional, and local plants? This will be determined by answering four questions: Will the product be distributed worldwide, or does it require regional customization? Are there legal obstacles to manufacturing from a single site? Does outsourcing offer an edge? Is senior management ready to make tough, and sometimes politically expedient, decisions?

Will the product be distributed worldwide, or does it require regional customization? This question is especially relevant for the industrial and consumer goods industries, as well as the automotive sector. And the answer is not always clear-cut. In the automotive sector, for example, high-end vehicles such as the Mercedes-Benz S-Class and BMW 7 Series tend to have global appeal and can be produced from a single plant. However, as several automobile manufacturers have discovered, there is little appetite for a global mass-market vehicle. In instances such as these, a regional network of plants is usually required to cater to regional tastes.

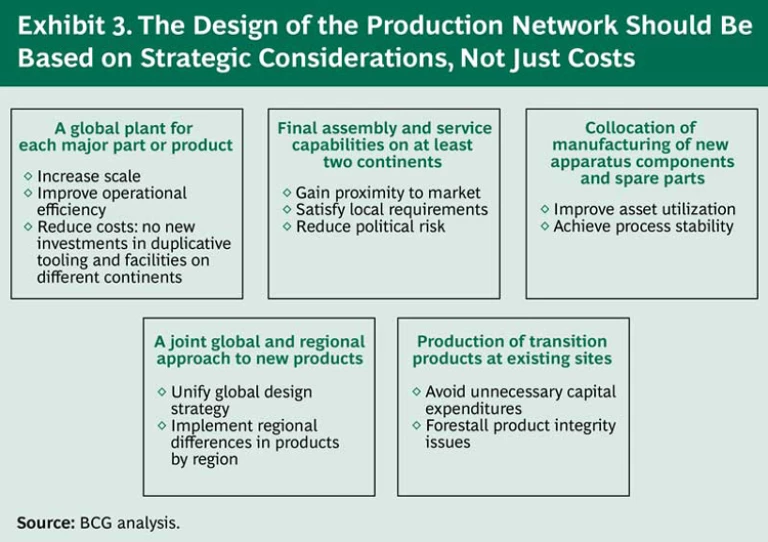

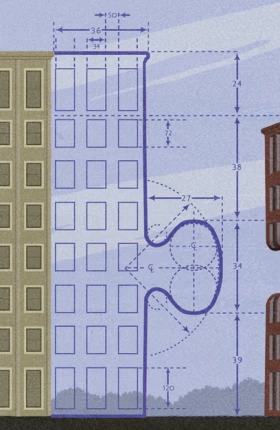

Technical constraints can also force a company down the regional route. In the power sector, for example, it would not be feasible to have a single, global plant for gas turbines for the U.S. and European markets because the two regions have different power requirements (60 hertz and 50 hertz respectively). Geopolitical risks also have to be factored into the equation: There might be a compelling economic case for concentrating production in one country, but what if the political situation in this location turned sour? How would this affect the company’s ability to meet demand? Exhibit 3 provides an example of guiding principles for production and network design.

Are there legal obstacles to manufacturing from a single site? Some countries impose high import duties on finished goods, making it prohibitively expensive to export to these countries. One solution is to have a global plant that manufactures core components, which are then assembled locally. While this solution can work with relatively low-value goods that require little technical expertise to assemble, in most cases a regional plant is required to manage the assembly and manufacture of region-specific components. The logistical cost of transporting components to different parts of the world—especially heavy or cumbersome items—can also make regional and local production facilities preferable. This is why the construction industry tends to favor a network of local plants.

Does outsourcing offer an edge? Which components are central to competitive advantage and which are not? Noncore components that are either standardized or capable of being redesigned to conform to industry standards should normally be outsourced. In the turbine market, for instance, most companies retain control over the production of hot blades and core elements of the rotor but outsource other parts of the machinery. Similarly, vehicle manufacturers tend to keep the production of the “holy trinity”—the engine, axle, and gearbox—in-house and buy the remaining components, although this is changing as vehicles become increasingly computerized. However, the decision to outsource is not always that easy. In many industries, such as the automotive industry, it also depends on the proximity of suitable suppliers.

Is senior management ready to make tough, and sometimes politically expedient, decisions? In any PMI, it is essential to make well-informed decisions as rapidly as possible in order to remove the destabilizing effects of uncertainty. This is especially important when senior management is dealing with the emotionally charged issue of plant closures. Any decisions to shut down or retain sites must be based on an objective, factual comparison of their total costs—including their relative labor and capital costs—and their relative productivity. Opportunities to improve the productivity and cost efficiency of underperforming sites by transferring best practices also should be explored. In BCG’s experience, this option is often underexploited. Pure economics, however, will not always decide the outcome. The potential impact of plant closures on a company’s reputation, which is much harder to calculate, also needs to be taken into account—especially in brand-dependent sectors such as consumer goods.

Sales and Marketing: Balancing Cost and Revenue Synergies

The biggest challenge in sales and marketing is striking the right balance between cost and revenue synergies. Although it might be tempting to think significant savings and revenue gains can be made by selling a larger number of products through a smaller combined sales force, it’s a much tougher act to pull off than many companies assume. In fact, there’s a relatively high risk that sales will drop, canceling out any cost savings from having a smaller sales team, unless senior management understands and addresses the challenges of an enlarged product portfolio.

One of the difficulties is that the acquirer’s and target’s sales teams often lack the knowledge and customer relationships to cross-sell each other’s products and services. This is especially true in highly specialized markets such as pharmaceuticals. In consumer goods and other brand-dependent sectors, there is also a danger that some of the brands in the combined portfolio will overlap. This can create two major problems. First, individual members of the sales force—who are driven by short-term targets—will almost always throw their weight behind the perceived winners and ignore the also-rans. The second and more critical pitfall is the high probability that retailers will refuse to allocate shelf space to brands that are closely related. The net result will be sales cannibalization.

Acquirers also have to contend with customers’ concerns over the combined entity’s new market power, which can prompt customers to turn to smaller, more pliable suppliers. Another challenge is the risk of staff defections, especially if sales—and commission-based income—start to decline.

With so many hurdles and uncertainties, it’s not surprising that acquirers often struggle to realize potential revenue synergies—which is why, of course, most mergers are predicated on easily calculated cost synergies. It’s much tougher to estimate revenue synergies and even harder—technically and emotionally—to contemplate the scale and likelihood of negative synergies (that is, a drop in sales).

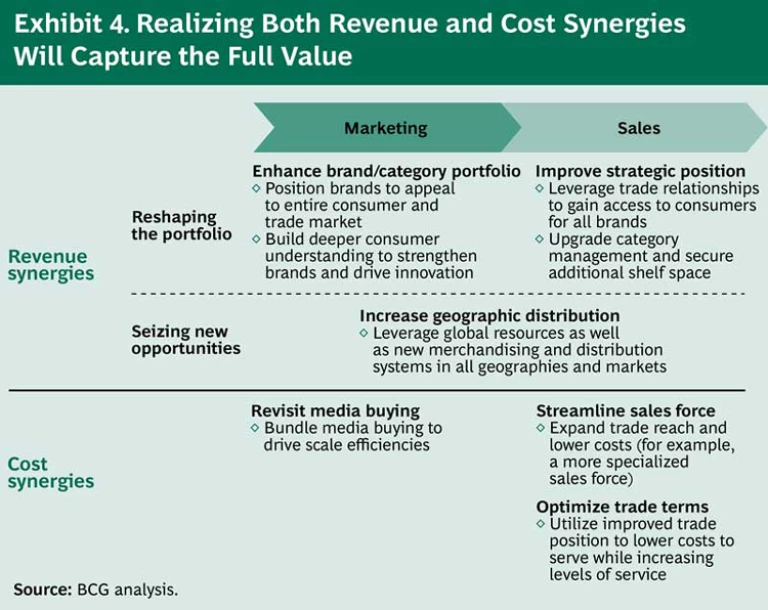

Nonetheless, numerous revenue and cost synergies can be realized—for example, by exploiting the enhanced geographic distribution of the combined entity or by bundling together media buying. (See Exhibit 4.)

Sales and Marketing: Balancing Cost and Revenue Synergies

Senior management should give four main issues special attention in order to maximize revenue synergies and avoid the risks of declining sales: managing the sales challenges of an expanded portfolio, reshaping the portfolio, keeping customers loyal, and dealing with “amputations.”

Managing the Sales Challenges of an Expanded Portfolio. The combined sales team needs to be educated about all products in the portfolio and provided with incentives to cross-sell these products as well as a clear and well-communicated sales plan that defines the role of each product in the company’s long-term strategy. Because sales teams often have entrenched views about “right” and “wrong” approaches, which can lead to conflicts, it is important to set a clear, top-down agenda that draws on the best practices of both teams. One large consumer-goods company addressed this issue by providing a combination of product training and role-playing exercises that forced the combined sales team to operate in the toughest possible conditions. This exercise highlighted the sales team’s strengths and weaknesses, and these insights were then used to develop specific guidelines.

Sometimes it makes sense to keep the teams separate—notably when the main gains of the merger are revenue synergies and there is a high risk of sales cannibalization because of product overlaps. Even in these situations, however, there are often opportunities to extract cost synergies by enabling the two sales teams—using well-defined guidelines—to share specific information and insights. At a major consumer-goods company, for example, the two sales teams operate independently—avoiding potential conflicts—but share and coordinate all brand and go-to-market strategies. They also exchange best practice and market insights. This has enabled the brands to retain their own identities while building on each other’s strengths.

Reshaping the Portfolio. The major challenge is to turn two sets of competing brands into a portfolio of complementary brands. Doing so requires aligning the positioning of all brands in the portfolio, determining category priorities, and planning and coordinating go-to-market activities to avoid cannibalization. A sporting goods manufacturer neatly sidestepped the potential conflict between its two brands by positioning one as an individual sports brand and the other as a team sports brand, while leveraging the combined entity’s expanded sourcing and marketing capability to lower the production costs of both brands and increase their reach. This strategy enabled the company not only to increase its margins and revenues but also to meet a broader range of consumer needs and offer products at more diverse price points.

Keeping Customers Loyal. As soon as a merger is announced, customers will have concerns about a variety of issues—from trade terms to possible supply disruptions—and will start to develop defense plans. It’s essential to manage these issues proactively and systematically from day one. Customers should be prioritized according to their relative strategic value and risk, and invited to hear and discuss the combined entity’s plans. Answers to key questions should be formulated well in advance of these meetings, together with a clear statement of the benefits of the merger to each customer. For consumer goods companies, it is equally vital to have a strong trade story—not only for the combined portfolio but also for each brand. The trade story should spell out how the merger will enhance the combined entity’s category management, innovation rate, marketing, and any other features that will benefit retailers. When one company did this through a series of meetings between its senior management and key retailers, its point-of-sale returns increased significantly.

Dealing with “Amputations.” Packaged goods companies are increasingly acquiring particular brands rather than an entire business, usually when a competitor rationalizes its portfolio and disposes of nonstrategic or underperforming brands. One of the problems with “amputated” brands like these is that they do not come with the full set of resources needed to sustain them. Acquirers should arrange for transition service agreements to ensure that the necessary support is available until the acquirer develops appropriate expertise and relationships. The agreement should include arrangements to transfer key sales personnel to the acquirer and to provide ongoing component sourcing as well as any other relevant support.

Thinking Outside the Functional Box

The key to success in any PMI is to treat the integration of different functions as a strategic opportunity, not a mechanical merger of organizational units and processes. It is vital that the short-lived appetite for change during PMI be harnessed to improve the long-term quality, efficiency, and strategic value of each function.

In many cases, unlocking the full potential synergies of an M&A will involve altering the processes, organization, and focus of individual functions. But it also will require finding new ways in which functions can operate more effectively and creatively together. Integrating procurement into early-stage R&D is a case in point. This is why a strong project management office, with cross-functional responsibility for implementing the integration, is so important, as we discussed in the first report in this series. The project management office has the overview and the authority to identify and encourage the necessary interconnections.

Inevitably, the challenges and opportunities of integrating functions vary by industry. In this report, we have focused on the issues that apply to all sectors. In a later report in our series on PMI, we will address industry-specific challenges.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following members of BCG’s writing, editorial, and production team: Barry Adler, Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Keith Conlon, Mary DeVience, Angela DiBattista, Pamela Gilfond, and Sara Strassenreiter.