Confronting “Change Fatigue”

It was not a pretty story. A large energy company, striving to overhaul support functions and reduce costs, was having a very tough time. The management team leaders had launched what they thought were the right change initiatives, and they believed they were off to a good start.

They were wrong. It soon became obvious that employees, less than engaged, were more likely to roll their eyes than roll up their sleeves when the new change requirements were explained to them. “Change fatigue” was ubiquitous. After all, the current effort was just the latest in a long string of change efforts—few of which had succeeded.

Even more worrisome: proof of resistance was everywhere, confidence in the company’s senior management was low, and there was little clarity concerning the factors by which employees were measured. Long story short: the changes went nowhere fast. In that respect, the energy company was no different from the myriads of other organizations that fail to do a proper job of delivering transformational changes.

Today, the company’s story is quite different. The targeted savings have been achieved—and are being sustained. Many of the company’s functions are cost-effective, thanks largely to motivated in-house teams of line managers. The key initiatives are explicitly defined and owned, and managers know which milestones the organization must achieve and when, as well as which course corrections they must make if a milestone is likely to be missed.

The executive team gives clear and meaningful direction and backing. Line leaders are engaged and feel supported; they know what they have to do to facilitate change. Communication about change cascades more easily and systematically down through the ranks.

The energy company’s ability to make change management work—to change change itself—is proof that achieving positive and productive change is entirely possible. In this report, we deconstruct the concept of a systematic, integrated approach to change management.

We show how organizations that focus energy, resources, and time on the most important change elements—as did the energy company described above—can make sense of the change management chatter and successfully achieve sustainable change as a result.

No Relaxing of the Case for Change

Organizations absolutely must do a better job of managing change because—clichéd though it might seem—change really is a constant. The volatility and turnover of industry leadership has more than doubled since 1980, according to recent BCG findings published in Harvard Business Review.

Corporations, government agencies, and nonprofits are hemmed in by heightened volatility, shifting economic realities, and rapidly evolving competition—forces that collectively mean that companies must adapt and restructure, and do so more frequently, more thoroughly, and faster than ever before.

More than 30 percent of business leaders polled in recent BCG research say that they are dogged by economic uncertainty. Nearly as many express concerns about increasing complexity and the pace of innovation and change.

Most corporations are trying to keep pace with change. For example, nearly 90 percent of those surveyed in a BCG study of executives worldwide (leaders at organizations with more than 1,000 employees) said that they had recently carried out a reorganization. Roughly half were large-scale enterprise-wide reorganizations—efforts designed to fuel global expansion, unleash innovation, capitalize on a market trend, cut costs, digest a merger or an acquisition, or respond to major social or economic shifts.

Yet few are succeeding. Customers’ expectations are rising faster than corporations’ ability to respond effectively. New global competitors are popping up everywhere. Products are becoming obsolete in no time flat. And technology’s march keeps pulling the rug out from under even the most forward-looking organizations. As common as transformations and reorganizations have become, what’s even more common is their high failure rate: at least half of all change initiatives fail to deliver the anticipated value.

Senior managers are deeply frustrated by the failures. “I just don’t get why things have changed so little after all we’ve done,” is a typical reaction to such frustrations. As Tom Enders, then CEO of Airbus, told Aviation Week in 2011, “Somewhere in the last 40 years we learned to save fuel and forgot how to take risks and manage them properly. We forgot how to turn our ideas into reality before they were out of date.”

What goes wrong with change efforts? There is no single answer. What we do know is that the immediate and lasting costs are not tolerable. (See the sidebar “The Persistence of Resistance—and Its Long-Term Consequences.”) What’s needed now is a systematic, disciplined approach that acknowledges the many real-world complexities of change and helps flip the odds in favor of success.

The Persistence of Resistance—and Its Long-term Consequences

Advice about change management is almost an industry unto itself. Given all the wise words of academics, consultants, and in-house experts, why are failure rates still so high?

There is no simple answer. Yes, there is the dead weight of history. Failure begets failure. Many organizations are on their umpteenth “transformation.” After several rounds in which nothing much changes, most employees—the all-important middle managers included—switch off when top management rolls out Operation Galvanize! or a similarly dubbed plan designed to rally gung-ho enthusiasm.

Real change is also dogged by fuzziness about the objectives. Change in the service of what? Then, there are the personal motivations of all the individuals who must begin to do things differently if the change effort is to succeed. That’s particularly true for the extended leadership team and middle management, who in many cases are simply informed of the impending change rather than being enrolled to help bring it about.

There is also the unavoidable fact that achieving change is tremendously difficult. Too often, change programs drown in oceans of initiatives rather than focusing on rivers of opportunity. They fail to emphasize the “minimum sufficient to win”—that is, the decisions and actions that will have the biggest, quickest impact. Absent any rigorous prioritization, the organization chokes on the profusion of change efforts, each of which is deemed important. Furthermore, the same managers are tapped for each and every new initiative, with the risk that they suffer burnout.

The immediate costs of failure to change are too familiar (and too depressing) to spend time on here. Arguably more pernicious are the lasting costs of failure—the factors that effectively teach the organization to resist change. It’s easy to see the negative cycle. Executives whose middle managers complain that “we’ve tried things like this before and they’ve failed”—and who themselves complain about resistance from the ranks—simply reinforce such responses when yet another change initiative does fail.

The story gets worse. The employees who resisted the changes end up looking like champs, and those apparently naive enough to cooperate end up feeling like fools. The message the cooperators get is loud and clear: don’t get caught again. The organization is now set up to fail. It is constitutionally unable to get out of its own way.

Toward Very Practical Solutions

So what does it take to build a real change capability? What is the right mix of skills and attitudes and behaviors that can be embedded in and institutionalized throughout the organization? The good news is that there is growing recognition of the need for change done right. Many boards have appointed CEOs with that explicit charter, and almost all CEOs recognize the need to take even successful enterprises to new levels of performance. The Economist Intelligence Unit found that 63 percent of senior executives polled said that they had been spending more time on their organizations’ most significant change initiatives over the past year.

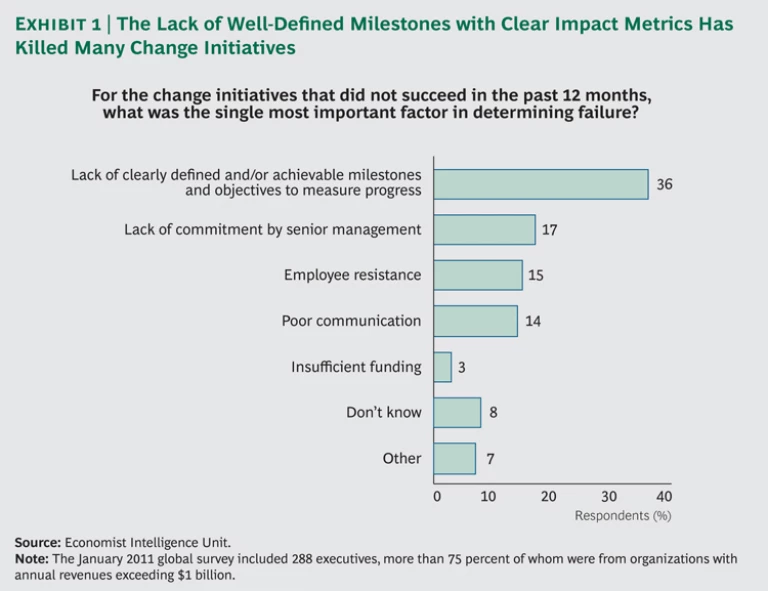

Most CEOs, especially those new to the position, must fundamentally transform their enterprises at some time during their tenure. Christopher Nassetta, president and CEO of Hilton Worldwide, found that out during a world tour of Hilton properties soon after he took the reins. “People were practically screaming it from the company’s rooftops around the world, very consistently, that we needed to really transform this company,” he stated. At the same time, senior executives are becoming much more aware of the factors that promote failure. (See Exhibit 1.)

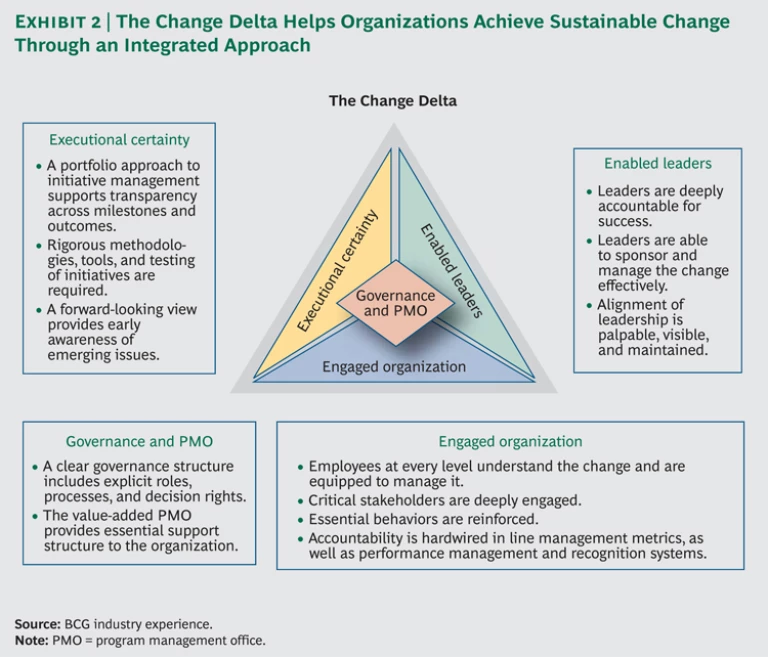

Working on change initiatives across several decades and in an array of industries, BCG has identified the distinct elements that come together to form what BCG calls the Change Delta—a set of success factors proven to help organizations achieve sustainable change through an integrated approach.

These elements consistently prove successful because they reduce the variability of results from a portfolio of change initiatives and allow for effective early course correction. Indeed, companies that have used the Change Delta approach have exceptionally high rates of meeting their targets while building organizational engagement and confidence in the future. (See Exhibit 2.) Let’s examine each element in turn.

Executional Certainty

More often than not, executional certainty is the preferred starting point for many conversations about change management—probably because it feels the most concrete and actionable. But the conversation almost always winds its way around and among the other Change Delta elements.

The insistence on executional certainty diverges from traditional approaches to change management. It comprises several major activities, all of which are sharply focused on results. It is tied to another essential of change management that we cover later in this report—establishing a governance structure with clear accountabilities. The structure must provide the minimum level of orchestration to ensure progress without being burdened with bureaucracy.

It’s important to define the necessary initiatives precisely, figure out the risks and interdependencies, and prioritize those that drive the bulk of the value. The approach must expose any and all emerging risks to the impact of those initiatives. Senior leadership has to be able to see the inevitable gaps that open up between change targets and actual change progress; it has to be easy for leaders to get clear operational insights so that they can respond quickly—before targets are missed—making necessary course corrections across the range of change activities by adjusting critical allocations of resources, time, and their own attention.

The underlying building block for this approach is what BCG terms the initiative roadmap. (A transformation program can have many initiatives, each of which can have several roadmaps.) The roadmap is categorically not a project plan covering a list of discrete tasks. Its purpose is to tell the story of the change initiative in such a way that executives, on the basis of monthly updates, can easily understand what is happening and can make course corrections to ensure ultimate on-time value delivery.

Roadmaps are made up of a number of milestones—in most cases, 15 to 25 are most effective—along with time frames, financial and operational metrics, and clear accountabilities. The milestones set a cadence for the overall change program, breaking it into manageable pieces that seem much more attainable for everyone involved. Equally important: individuals and teams—and eventually the whole organization—steadily build confidence not only in the potential success of the transformation effort but also in their individual and collective ability to identify, launch, manage, and succeed at change at any time.

Most important, an initiative roadmap articulates the key risks of and lead indicators for delivering the financial and operational impacts; it ensures that these are tested at critical points, and it signals when and how financial and operational outcomes will be triggered. Conventional change efforts typically have overall financial and operational goals, but the roadmap approach of tying such goals to individual milestones proves to be a far more successful way to achieve the promised value.

Furthermore, linking measurable KPIs to milestones means that red flags will appear much earlier than in typical implementation exercises. (An example milestone might be the hiring of a designated number of sales personnel with a particular new skill set. Achievement of the milestone is a prerequisite for reaching a sales target in a new channel within a specified timeframe.) Bad news becomes good news: as the roadmap owner updates the roadmap, typically monthly, the fact that an indicator is flagged red means that there is an opportunity to act in time to ensure delivery of desired results. Typically, red indicates failure, but that’s not necessarily so when effective early-warning indicators and financial goals are tied to milestones.

Of course, not every milestone can be defined in such quantitative terms. Typically, only 20 to 30 percent of milestones have impacts attached to them. To help gauge the robustness of each roadmap, truly change-capable companies use formal rigor-testing processes. (See the sidebar “Why It’s Smart to Rigor-Test.”)

Why It’s Smart to Rigor-Test

Just because there are plans for each initiative of the change program doesn’t mean it will be smoothly translated into action or will generate the intended value. There are many unknowns, risks, and interdependencies that can quickly scramble a plan.

That’s why BCG works with roadmap owners, sponsors, the PMO, finance, and HR representatives to apply a strict rigor test to each initiative’s roadmaps. At first glance, the test includes a set of seemingly obvious questions. Is the roadmap clear enough to be readily implemented? Are the benefits and timing clearly and correctly identified? Are the risks and issues explicit enough? (See the exhibit below.) If such questions are not asked and answered, more than half of the initiatives are likely to fail.

The rigor-testing discussion is often the most influential among the many conversations that PMO staff will have about each initiative in the program portfolio. While every discussion is slightly different—customized to the organization and its needs—the 16 or so core questions, in three groups, are much the same.

Essentially, the rigor test significantly strengthens both the local-level considerations of people-related issues such as communication planning and stakeholder discussions. It also reinforces the delivery of the intended operational and financial impacts, addressing what the Economist Intelligence Unit has found to be the single biggest management challenge—a lack of clearly defined or achievable milestones and objectives to measure progress.1 The test, which typically takes up to one hour, exposes the roadmap to much higher levels of upfront discussion and scrutiny, making sure that the milestones are clear, there is consensus about the impacts, and the assumptions driving intended impacts are articulated and validated. It also helps to ensure that the risk points are well understood, the appropriate risk-testing and mitigation measures are in place, key stakeholders have been identified and are being or will be effectively engaged, and every aspect of the endeavor that must be communicated has been or will be communicated.

Is rigor-testing worth it? It certainly is. BCG’s analyses—mapping the outcomes of thousands of such tests over several years—indicate that high-quality rigor-testing allows for the capture of more value. In fact, the roadmaps whose rigor tests earned “excellent” scores captured an average of 130 percent of their planned value compared with 100 percent of planned value for those with “marginal” rigor-test scores. Clearly, the incremental value derived from rigor-testing is compelling. Even a marginal “pass” rate means that a roadmap is very likely to fully deliver against plan. Roadmaps with lower scores do not pass the rigor test and therefore are stopped or, more likely, reshaped and replanned.

There is a good example in the story of a major railroad that was investing heavily to improve its on-time record. By applying a rigor test, the railroad was able to develop a clearer view of some of the risks associated with implementing its on-time initiative, enabling its leaders to actively manage the risks. The test helped ensure that leading indicators were built into the roadmap before it was launched.

For instance, the railroad developed a measure that correlates trains’ on-time arrival with how quickly passengers move on and off the trains and across the platform. Building a milestone for passenger movement into the roadmap—and quantifying its impact—made it easy to see its importance and to ensure that it would be regularly tested against once the roadmap was launched. In implementation, managers quickly diverted resources to ensure that employees who coordinated traffic on the platforms were able to take on new, more public roles, interacting with commuters and managing the flow of crowds at these stations. This response caused on-time performance to increase substantially and remain at this higher level.

Senior leaders next think through the “how” of tracking and managing the initiatives that matter most. Typically, we find that the 80-20 rule applies: roughly 20 percent of initiatives drive 80 percent of the value. Only the few initiatives, typically those with large financial value or critical cross-functional enablers, require transparency up, down, and across the organization; they include only the information that the leaders need in order to have confidence that progress is on track or to know when to intervene and make course corrections. By selecting a reporting mechanism that delivers exception-based reports on just these critical initiatives and by flagging early-warning indicators, business leaders remain engaged and can more easily and effectively resolve issues. (See the sidebar “Exception-Based Reporting in Action.”)

Exception-Based Reporting in Action

An exception-based reporting mechanism can make a big difference in the delivery of business value. Management at a large mining organization discovered this while trying to boost the output of the company’s extraction operations. The team leading one of the ten roadmaps for the company’s manpower-planning initiative had identified the recruiting of miners formally certified in occupational safety, health, and environment (OSHE) skills as a critical leading indicator for the successful launch of a new shift.

However, due to an existing skills shortage, the team was hard-pressed to recruit the 120 miners needed to launch on schedule in October, three months later. Top management rapidly recognized the challenge when the initiative team updated its roadmap and showed that the KPI for OSHE-certified miner recruitment was falling short of plan, in turn triggering an exception in the next executive report.

As a result, the organization’s human-resources chief jumped into action, setting up a temporary task force to bolster hiring for the remaining three months. The outcome: the company found its new recruits and started the new shift on time in October.

Woven into the executional-certainty element is the issue of respect for the individual—a crucial point that is regularly overlooked and too easily dismissed as “squishy.” Respect must be reciprocal: from managers to employees, disclosing the need for and nature of the change and signaling commitment to support employees when challenges arise; and from the employees to managers, committing to deliver and share information promptly and accurately when things are not happening as planned.

This contract of respect contributes to an atmosphere of transparency and partnership in the delivery of results. There can be no “shooting the messenger” in an environment in which problems are recognized early on, allowing far more opportunity to make course corrections that work. If, in effect, the organization tolerates, or even rewards, the hiding of failures or shortfalls while punishing requests for support, there will be less transparency, and ultimately productive course correction won’t be achieved. The emphasis has to be on solving problems, not apportioning blame.

When the issue of respect is an explicit part of the project roadmap, and when it pervades the change effort—and, ideally, the whole organization—there is a much greater likelihood of success: information shared is accurate and timely and fully reflects concerns, and leadership is now positioned to take a more proactive, effective stance on decision making.

Enabled Leaders This element of the Change Delta starts with the top team’s commitment to open, forthright, no-holds-barred discussion of the need for change and the objectives of a change effort. There can be no “undiscussable” topics among the management team members—no shrinking from debates about turf, power, or spans of control. There should be more than one or two or even three discrete discussions; the guts of change are that important. “Never assume that leaders get it,” said the program sponsor at a global oil and gas company. “We need to take probably ten times as long in engaging, empowering, and educating our leaders as we actually think we do.”

One thing that business leaders have certainly learned about change is that it cannot be mandated by the CEO alone. CEO support is necessary but not sufficient. What’s needed is the enrollment of the extended line leadership team. That’s what happened at ING, a Netherlands-based banking conglomerate, during a major change initiative. (See the BCG article “How ING Bank Took Change to Heart,” December 2012.) ING made serious commitments of time and effort to win over its extended leadership. To launch detailed discussions of the combined organization’s brand values and the behaviors needed to support them, ING held four sessions a year for the top 300 managers in its retail and IT operations. At the first session, the CEO himself explicitly laid out the expected behaviors. There was also a full day of interactive training for the top 1,000 managers, distributed among carefully orchestrated workshop groups of 60, to translate behaviors into practical realities. These sessions included development of an individual plan for each manager.

Over the next six months, repeated training sessions drove home the big change messages and engaged middle managers in determining what the organization should keep doing, start doing, and stop doing. In the sessions, managers were provided with information, training, and tools that would ensure that messages cascaded down to junior managers and employees.

To be candid, though, the enablement of an organization’s leaders must be a very practical catch-as-catch-can exercise. In many cases, senior executives lack the luxury of the time required to bring in lots of new blood or embark on long-term leadership-development programs designed to spur change. And they likely have to work with the leaders they already have, regardless of the levels of their capability. There is no time to wait until conditions are perfect: things have to happen in the next four to six months—not the year to three years it can take for major leadership-development efforts to work. The key question is: How do we best support the personnel we have?

The answer to that question is rooted in the extent to which each leader truly “owns” the change agenda—and is seen to own it. Each leader should be continually aligned with his or her peers; the alignment must be palpable, visible, and evident to all in the way the entire management team communicates and embodies change, doing so in unison. And it should go without saying that all the leaders should have the skills and knowledge to manage change effectively and to pick lieutenants and key team members who can augment their efforts.

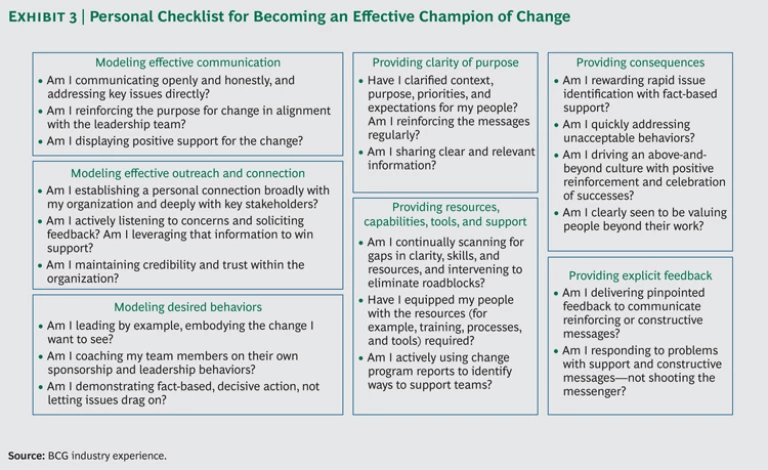

Throughout, leaders must continually, visibly, and authentically act as role models for the change. Furthermore, they must not tolerate the tendency to slip into old habits. The moment that senior managers are perceived as merely paying lip service to the change efforts, those efforts are doomed. An effective change champion models sponsorship of the effort, enables employees to achieve the declared goals, and drives accountability for the outcomes. (See Exhibit 3.)

In making personal changes to become better sponsors, leaders often benefit from an outside-in view of how others in the organization perceive their behaviors. Data coming from focus groups or short surveys can prove helpful in bringing leaders to a common understanding of the impact of their actions and decisions, as well as the consequences of inaction and failure to make decisions.

A case in point: When a global biopharmaceutical company was conducting a program aimed at achieving significant productivity improvements, alignment of the senior team with the targets and the means to achieve the targets were spotty at best. The manager of the program management office (PMO), a well-respected former business-unit leader, advised the CEO that the program should be halted until the leadership group could come to terms. The CEO supported this move, putting pressure on the group to work through their differences quickly—especially since targets had already been communicated to investment analysts.

Once key concerns had been fully aired in a supportive environment, the group worked through a range of specific issues and was able to cascade this alignment effectively to the line leaders below them. The results of the overall effort actually exceeded the targets, enhancing the group’s self-confidence in managing change.

Engaged Organization The organization has to be engaged down deep. If a critical mass of the workforce and middle management doesn’t buy into the change effort, then senior management may as well not try to push it through, no matter how well the other elements of the Change Delta are handled. It is crucial that people at every level understand and be prepared and able to manage the change. The change program sponsor at a leading global medical company said, “People face constant uncertainty in their lives. Given the stress they are under these days, you must be empathetic and flexible, and you must address the uncertainty if your change effort is to be successful.”

This element of the Change Delta defines and supports the necessary changes in ways of working at many levels, making sure that appropriate behaviors are reinforced and hardwired into systems and structures. The understanding and mandate for individual behavior change should be cascaded down through the organization. Behavioral change will not show up organically everywhere at once. To successfully cascade the enrollment of the organization all the way down to the grassroots employees, senior managers have to be able to help their people answer key questions such as, Why do we need to change? How will this change affect me and my colleagues? If I change, will my boss change too?

It is important to adhere to a clear, systematic process for clarifying roles, responsibilities, and leadership behaviors down through the ranks; for assigning accountability; and for determining decision rights. This is one area in which leaders often fail for the simple reason that, in the absence of a structured process and candid debate, it is especially difficult to get it right. BCG has found that companies that use a structured role-clarification process are more likely to experience superior economic performance than those that don’t.

Overall, engagement is especially important when it comes to key supporters—and skeptics. The process of identifying and prioritizing stakeholders by their level of support for the change effort and their degree of influence in the organization promotes targeted engagement. We find that in many cases, influential supporters are underleveraged and skeptics underengaged. Effective stakeholder engagement sees business leaders arming influential supporters as change agents, giving them the information and messages they need to influence the organization.

At the same time, it requires real backbone to deliberately engage the skeptics. (See the sidebar “Never Shut Out the Naysayers.”) The upside is enormous though.

Never Shut Out the Naysayers

It is not uncommon for business leaders to inadvertently ignore or shut down those who voice opposing opinions. Yet the naysayers often have good grounds for their skepticism. And when they feel that their points of view are disregarded or disrespected, bad situations quickly become worse.

A large commercial and retail bank had embarked on a major change program designed to offer a much better customer experience at far lower cost. The program meant extensive restructuring of back-office activities: a fundamental reorganization, greater use of technology, significant process redesign, site consolidation, and a workforce reduction of 30 to 40 percent.

Most of the senior executives had been with the bank for decades and were not particularly open to change. Moreover, many of the rest of the employees had been with the bank for most of their working lives. An initial assessment of the change program’s likelihood of success (a review of the duration and phasing of the project, the capability of each initiative team, the overall leadership and local commitment to change, and the additional effort required of staff) helped reveal the extent of stakeholder resistance—and the degree to which it had to be actively managed. The assessment, which BCG refers to as DICE, also shone a light on the need for a better-aligned message cascaded from the leadership team.1

To identify employees whose enthusiasm would be critical to the success of the effort, the top team used an influencer matrix—a simple but powerful prioritization of stakeholders along the two most critical dimensions: the level of their support for the change effort and the degree of their influence in the organization. (See the exhibit below.) The matrix helped the team determine whether and to what extent specific employees or groups were supportive or unsupportive. The matrix also guided the team’s hypothesizing about why certain critical employees might not show support and helped the team form constructive responses. The process of prioritizing and gaining a deep understanding of a select group of stakeholders—in this case, approximately 1 percent of the employee base—focused resources efficiently, producing real impact.

Regardless of how supportive the stakeholders are, respect is pivotal to success in change efforts. But respect does not imply overly inclusive or naively optimistic programs. Not everyone will be—or needs to be—a direct agent of change. In the same vein, treating people with respect doesn’t necessarily mean being “nice” to them or failing to make the tough decisions. But it does mean being honest with them. Some individuals may not have jobs when the change initiative is complete, but if they are addressed candidly and fully, and given every care and concern in terms of best-practice outplacement, they are far less likely to throw darts from afar.

At the very least, you win their respect by hearing them out and potentially learn a thing or two about real-world obstacles to change. At best, you win them over, and they become passionate advocates for change. In many cases, the influential supporters are uniquely positioned to play key roles in converting skeptics.

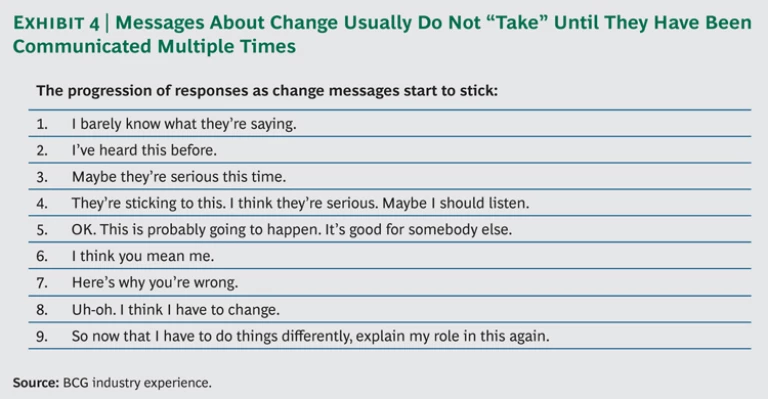

Of course, engagement is very much about great communication—clear, candid, constant, consistent, and two-way. “Generally people are not afraid of the unknown. They are afraid of the unexplained. A true leader shines a light on the road ahead to help others see where they are going,” one midlevel supervisor at a U.S. bank said when asked about his greatest frustration in implementing change. Such communication efforts start with active, effective listening to recognize and enlist the most critical stakeholders. These efforts involve rehearsal—lots of it—of the key messages. The process cannot be rushed and must be repeated, because there is inevitable “signal fade” as the message is transmitted throughout the organization. BCG has found it can take up to nine conversations to ensure that key change messages really do stick. (See Exhibit 4.) When senior leaders feel that they are communicating about three times as much as they ever thought they would need to, they are probably hitting it right. Moreover, it is really important to communicate in small, interactive group settings.

The hard facts of change—why, what, when, who, and, most important, what is in it for each individual—are the essential components of the conversation, to be sure. But leaders will have to communicate less tangible factors—pride of workmanship, job satisfaction, and self-worth to win the teams’ emotional buy-in for the changes ahead. After all, they will be asking busy people to use their time differently while ensuring that the incentives are in place to reinforce the new ways of working. They must not threaten with if-you-don’t-do-this messages: there should be four times as much positive reinforcement as negative. Additionally, leaders need to be careful not to alienate people by sounding too critical or dismissive of earlier change efforts.

Last but not least: a proper engagement effort works to nourish all three facets of an employee’s contribution: attitude (willingness to change), skills (ability to change), and knowledge (experience of how to change). Where skill or knowledge is deficient, it’s necessary to acknowledge and invest in building additional skills through training, coaching, and developmental assignments and experiences (although in practice, this isn’t often done). For employees who are unwilling to change, the goal should be to improve their confidence that change will happen and that they can be valuable contributors in shaping the future. Leaders need to convey the vision for change and the scope and trajectory of the effort needed to realize that vision. They also have to give employees confidence that the leadership team will stay the course, steering effectively; sending consistent, aligned, and repetitive messages; and implementing symbolic actions that underscore the desired changes.

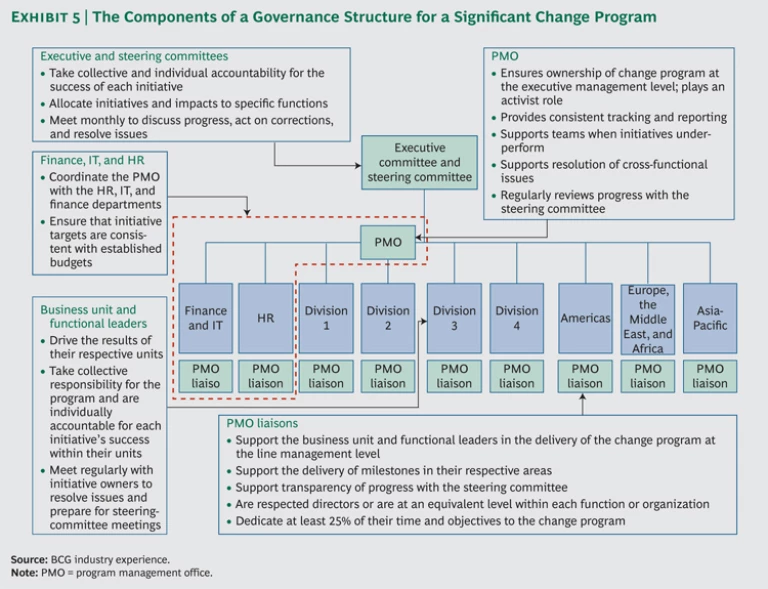

Governance and PMO If the three preceding elements are the arms and legs of a real change effort, then the governance, program management disciplines, and the role of the PMO are its nervous system. The fundamental idea: to have a way to keep top executives engaged and updated on critical milestones, planned operational or financial impacts, and emerging risks, and to provide them with the right information at the right time to take action.

Successful large-scale change requires engagement and support at the highest levels of the organization. In most cases, there is a steering committee comprising some or all of the sen-ior team of leaders likely to be affected by the program. The committee members act as sponsors for key initiatives, providing guidance, solving immediate problems, and removing roadblocks, and they energize the broader management team and celebrate success.

In general, it is critical that key governance bodies allocate time for regular reviews and resolution of key issues outside of meetings. At ING, this was very much the case. The board of directors was heavily involved from the outset, committing significant time to getting the change journey right. During the critical early months of its effort, the steering group at another large organization—a global financial-services provider tackling a particularly complex and challenging change program—invested a full three days per month in preparation, issue resolution, and review meetings. The group provided recommendations to the executive committee, which in turn invested a day each month in deciding unresolved issues, reviewing progress toward the targets, and tracking investments.

Change is created and delivered by line managers and their teams, but this happens effectively only when accountability is made explicit using robust governance structures and when the managers are armed with the information they need to facilitate timely decisions and actions. Given the challenges associated with information collection, data flow, and issue resolution in any complex program, a PMO is often the “glue” that binds together the necessary data, conversations, and decision making among senior executives, initiative leaders, and the line organizations. This is crucial for complex cross-business initiatives. (See Exhibit 5.)

The PMO plays several important roles. It works with the leadership team to set an appropriate pace of change, supporting the creation of a detailed timetable and putting in place the mechanisms that make it possible to meet every deadline. It acts as the steward of the aspiration for change, elevating and highlighting inconsistencies in understanding, processes, and language across the enterprise. It is important—but often quite difficult—to have consistent ways of creating a baseline, developing the plans for the change initiative, tracking against those plans, and flagging the significance of any deviations.

To make sure that sufficient value is being delivered on time, the PMO supports executive sponsors in rigor-testing the various roadmaps prior to the launch of the initiatives. As a result, the organization’s leaders have the forward-looking indicators they need to raise warning flags, giving themselves enough time to act effectively. When issues do arise, the PMO helps make sure that the right conversations are occurring and that rather than being blindsided, the line leaders are enabled to take action. The PMO does not need to be liked, but it should have broad-based respect. “PMO used to be a dirty word around here. This PMO has changed that,” remarked a senior leader at a global oil and gas company where the PMO is now recognized as a key part of a Change Delta approach.

Overall, the governance structure gives leaders the enterprise-wide view they need to steer the program to a successful outcome. Without breadth of view that encompasses both the change program and business as usual, costs can balloon in functional areas outside the scope of the change effort.

In almost any endeavor, clear roles and guidelines make things more efficient. Improvisation has no place in the unforgiving business of change. Governance and the organization structures to enable it are must-haves.

In Unity Is Strength So how should the Change Delta elements be viewed?

Companies aiming for change management success should not consider the Change Delta elements to be an à la carte menu from which they can pick and choose. All the elements are important and interdependent. Each element augments and supports the others, giving propulsion to and confidence in the overall change journey. You cannot deliver executional certainty without getting the extended leadership team to really shape and own the change, and the change will not stick unless the organization is engaged right down to the grassroots level.

The Next 100 Days

Change done right is never a one-off project. It is a set of reliable, practical capabilities that harness the energies of the entire organization time after time. The emphasis is on the practical: the Change Delta approach helps sharpen the focus on the change activities that matter most and gives business leaders the tools they need to ensure success.

Time and change wait for no one. Leaders who are embarking on change initiatives have only a matter of months to establish “change credibility,” to be able to say, authentically, that things are starting to be really different. (See the sidebar “Signs That Change Is Here to Stay.”) BCG strongly recommends looking at what can be achieved in the first 100 days of a change effort. To shape that journey, executives should consider how well their organization is aligned with the Change Delta elements and should ask themselves questions such as the following at the next management meeting.

Signs That Change Is Here to Stay

Talk with executives who are well able to handle change, and you’ll find that the tenor of the conversation is quite different from what you’d hear at organizations that still struggle with change. The following comments are characteristic at the companies in which change is starting to take hold.

- We seem to be getting more systematic.

- For the first time ever, we know where the results are supposed to come from, where all the money is supposed to be, and who is on track to deliver.

- For efforts in which we are likely to fall short of the target, we’re having really productive conversations about how to fill the gap between current performance and the target and about how to restructure the initiative in a timely manner.

- The PMO used to tick me off, but this one feels different.

- I’m not sure my people always like the role the PMO is playing, but it’s getting respect.

- Wow. These quick wins really have been quick and they have been wins.

- This has pushed us to communicate sooner about what we know and what we don’t know.

- Now I see that even though we execs may get it, the folks on the ground may not.

- It’s brought our extended line leadership team into the loop; these leaders feel respected because we gave them the necessary information in advance, and they had time to reflect on it and help shape some of the recommendations.

- I’ve seen executives call each other out on unproductive behaviors. It even happened to the CEO, and he was receptive to being called out.

- This is the first time someone has sat down with me and really explained why this is necessary and how it affects me. It’s been much more personal than prior changes the company has undertaken.

Executional Certainty. It is crucial that executives have a forward-looking view so that they can get fair warning about emerging issues that might trip up the change effort. As such, they have to make full use of rigorous change methodologies, tools, and testing of initiatives. And they must take a portfolio approach to initiative management. Key questions for discussion include the following:

- Do we know which initiatives represent the bulk of the intended value?

- Who is accountable for each initiative?

- Does leadership share an aligned view of the priority initiatives for the enterprise and for each business unit and function? Are resources allocated appropriately?

- Does the operational and economic impact of each initiative plan reconcile fully with the originally approved business case?

- Have we articulated in detail what will trigger the financial and operational results so that we’re not just notionally associating value with an initiative?

- Are key risks embedded in milestone descriptions so that they can be tested against regularly?

- Does each initiative plan include local communications and stakeholder engagement activities?

- Are we confident that we’ll know in advance when value delivery might slip? Have we given ourselves enough time to make course correction changes?

Enabled Leaders. Change leaders are deeply accountable for success. They are able to sponsor and manage the change effectively, and their alignment with each other is visible and sustained. The test of a true change leader starts with questions such as these:

- Do our leaders, at different levels, all describe our goals and rationale for the change effort in the same way?

- Can our leaders describe the implementation process and plan?

- Can our leaders clearly articulate, in an aligned fashion, the leadership behaviors required to deliver the change? Are they balancing the energizing of teams with the driving of accountability?

- Are our leaders spending more time listening than talking?

- Do our leaders actively identify and act to remedy unproductive behaviors in direct and supportive ways?

- Do we have a well-respected executive who is devoting a significant chunk of his or her time to the visible day-to-day leadership of our transformation program?

Engaged Organization. To ensure that employees at every level understand the change and are equipped to manage it and to make sure that accountability and performance management are hardwired in the performance metrics, executives have to be able to answer these types of questions:

- Are we segmenting our stakeholders in order to leverage the influential supporters and engage the skeptics?

- Is the communication plan replete with talking points, scripts, and answers to frequently asked questions? Does it include enough small-group conversations?

- Is communication tailored for all significantly affected groups?

- Are we collecting and acting on feedback about the progress of how communication cascades in order to keep the message clear and strong all the way down the ranks?

- Are new accountabilities made personally relevant and clear to each affected individual? Have incentives been adjusted as appropriate?

- Is there an appropriate balance of positive and negative reinforcement in place to encourage and support desired behaviors?

Governance and PMO. A clear governance structure includes explicit roles, processes, and decision rights. The PMO orchestrates essential information and provides support to the organization. Executives can begin to get governance and the PMO’s role right by asking these questions:

- Has senior leadership given a clear mandate for the PMO, executive sponsor roles, and other steering-team roles identified for the program?

- Do line leaders own their roles as sponsors and work to quickly and effectively make course corrections in response to any emerging issues?

- Does the flow of information support effective, timely decisions?

- Are we tracking and managing critical team activities beyond basic execution of the initiative—for example, the deployment of stakeholder management plans and management of complex interdependencies?

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to offer their sincere thanks to Angela Arnold, Mary Barlow, Kilian Berz, Jeanne Bickford, Rolf Bixner, Christian Branum, Jennifer Bratton, Evelyne Brooks, David Brownell, Taz Chaudhry, Patricia Clancy, Curtis Davies, Joe Davis, Erin Deans, Cindy DeTar, Jeanie Duck, Andrew Dyer, Chloe Flutter, Grant Freeland, Marc Gilbert, Marin Gjaja, Steve Gunby, Jim Hemerling, Tim Hoying, Rune Jacobsen, Judy Johnson, Larry Kamener, Matt Krentz, Jason LaBresh, Maury Leyland, Tom Lutz, Steve Maaseide, Fiona MacLeod, Joe Manget, Sharon Marcil, Bjorn Matre, Yves Morieux, Ned Morse, Zarif Munir, Brad Noakes, Christian Orglmeister, Martin Reeves, Anthony Roediger, Michelle Russell, Jürgen Schwarz, Robert Sims, Harold L. Sirkin, Aaron Snyder, Rainer Strack, Peter Tollman, Andrew Toma, Roselinde Torres, Mel Wolfgang, and other BCG colleagues for their contributions.