The majority of consumers in the world’s richest markets say they are feeling insecure and anxious and are struggling to save. They have tightened their belts and are buckled in for a sustained period of low or no income growth—a world that feels like the 1930s or the Lost Decade in Japan. In many markets, consumers’ worries are more intense than they were a year ago, hovering near the peak levels of 2008 to 2009. This sense of despair provides opportunities for companies able to aggressively segment their customers, deliver low-cost solutions, and provide a moment of salvation in the form of affordable luxuries.

Among the key findings of The Boston Consulting Group’s eleventh annual Consumer Sentiment Survey, conducted in April and May of 2012 and covering more than 22,000 consumers in 16 countries:

- Consumers blame the government for continued economic turbulence.

- Feelings of financial insecurity are intense and are increasing in most markets.

- Pessimism about the speed of economic recovery is rampant.

- One in four people, on average, in the U.S. and Europe is worried about job loss.

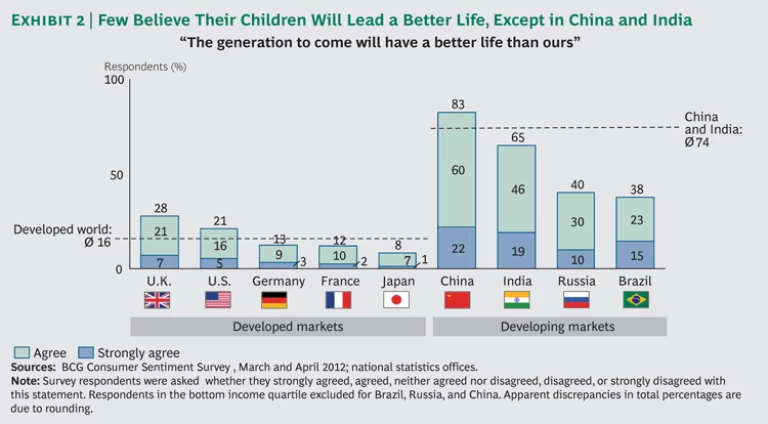

- Few believe that their children will live a better life—except in China and India.

- Values such as saving money and staying healthy have skyrocketed in importance, while the stated willingness to splurge on luxury items has plunged.

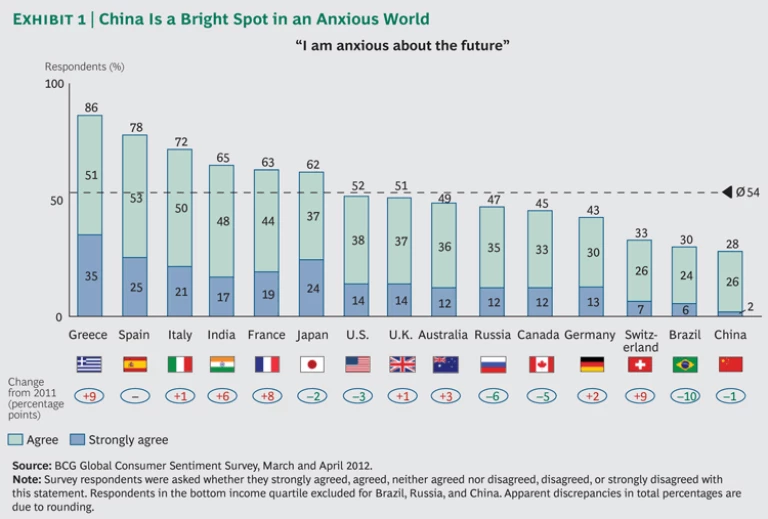

- China is a relative bright spot, with consumers there feeling more optimistic about the future than their Western counterparts. (See Exhibit 1.) But even in China, anxiety is up in certain consumer segments.

This widespread pessimism provides opportunities for companies that innovate to create products and services with more features and options at lower prices. It also bodes well for retailers with efficient and effective distribution systems. The crisis of confidence is likely to translate into three specific consumer behaviors: investment in education, increased savings, and a hunt for value.

The Nonrecovery Mindset

From the perspective of middle-class consumers in the U.S., Japan, and Western Europe, the world is still lurching from crisis to crisis. Americans, in particular, are anxious about their future, their jobs, and their lack of savings. Some 14 percent of U.S. households report that they are in financial trouble and an additional 34 percent say they are not financially secure.

Consumers have witnessed many recessions in the U.S. since World War II, but the Great Recession has been different. In previous recessions, consumers would get hit by a downturn and there would be a wave of unemployment, but there would always be a bounce-back, with the economy recovering in a miraculous way—and lifting everyone in the process. But in this recession, we got hit harder than ever before. From 2007 to 2010 in the U.S., real housing prices decreased by an average of 5 percent per year, real GDP growth averaged only 0.3 percent per year, and unemployment more than doubled—from 4.5 percent to nearly 10 percent.

And for the vast majority of consumers, there has been no bounce-back. Prices have increased, the cost of living has increased, unemployment is still at a very high level relative to post-recession periods in the past, and consumers feel they have less money to spend. They tell us in very emotional language that the recovery will take place very slowly—a consumer at a time—as a result of personal choices and luck: one consumer getting a better education; one consumer getting a college degree; one consumer becoming an engineer, a mathematician, or a chemist; one consumer getting the right job; one consumer earning a higher income.

Consider these quotes from our U.S. survey respondents: “[I fear] the economy will crash, gas prices will skyrocket, there will be no more social security” and “[My dream is] to find a job where I don’t have to kill myself for very little money and where I know I can provide for my kid.”

This level of anxiety and anger is common across the developed world. Respondents in Europe cite continuing turmoil and government failure to deal with the root causes of the debt crisis as major concerns, but conditions vary from region to region. Respondents in Germany and Switzerland are relatively positive about spending and are the least likely to change their behavior as a result of the crisis, whereas those in Greece, Italy, and Spain say they are being forced to change their spending habits drastically.

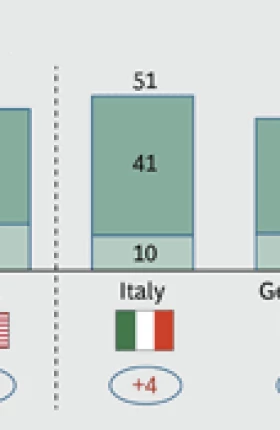

Fully one in four respondents in the U.S., France, and Germany—and even more respondents in Italy, Spain, and the U.K.—feel insecure about their jobs. By contrast, only 12 percent of Chinese feel this way. In Japan, more than half of consumers surveyed say they expect to be earning less in ten years than they do today, and a similar percentage report feeling financially insecure (more than in any other market in our survey). Nearly half of Western consumers believe that the economy will not improve, and a majority of respondents across the developed markets tell us they are anxious about their future—compared with 28 percent in China.

Stress has become part of daily life for many consumers, with about 43 percent of female and 39 percent of male respondents in the U.S. agreeing that “I feel a great deal of stress in my life.” Women, in particular, are under massive time pressure, with 48 percent agreeing with the statement “I never have enough time for myself.” So, too, are the poor in the U.S.: nearly half of lower-income respondents say they feel a great deal of stress, while only 32 percent of high-income respondents feel this way. Money may not buy love, but it does appear to buy some relief from stress.

Only one in five consumers in the U.S., France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the U.K. believe that future generations will have a better life than theirs, which means that roughly 80 percent of consumers in the Western world do not believe that their kids will have a better life. (See Exhibit 2.) Japanese are the most pessimistic—less than 10 percent believe the next generation will have a better life. As one respondent to our survey observed, “The glass is not half full, it is empty.” For many long-term unemployed and underemployed Americans, the sustained economic uncertainty is haunting. And whom do they blame? They blame their government. They say that the government is responsible and has failed to act on their behalf.

Struggling to Save

In most markets, consumers think the economy is fragile. While the idea of saving more is appealing to most consumers, those at lower income levels, in particular, tell us that they don’t earn enough money to save. BCG has conducted its Consumer Sentiment Survey for over ten years; at one time, U.S. consumers were among the world’s most optimistic. But now they are beset with worry about the future, the economy at large, the prospects for their children, and the fact that they do not have a savings account to fall back on.

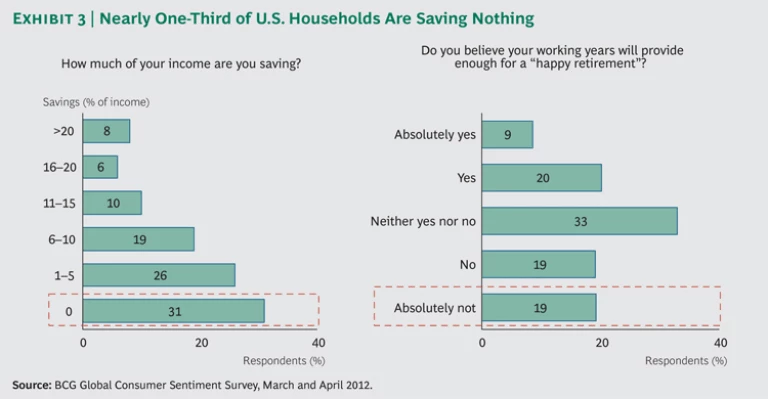

Thirty percent of U.S. consumers say they save none of their income. Some 57 percent of households are saving less than 6 percent. (See Exhibit 3.) For low-income households in the U.S. (those that earn less than $25,000 per year), there is very little discretionary spending. Housing, transportation, basic food and apparel, and some insurance consume all their cash, and there is nothing left over. Any actuary will tell you that to have a comfortable retirement, you have to save roughly 15 percent of your income. Yet only 14 percent of U.S. respondents told us they are saving more than 15 percent, only 8 percent claim to be saving more than 20 percent, and a little over a third do not believe they will have enough money for a “happy retirement.” It is not surprising that they are stressed, anxious, and insecure. Japanese and Greeks are the most worried about their savings for a happy retirement, with only 15 percent expressing confidence in their prospects.

In this situation, the vast majority are focused on trying to cut back. Across almost all demographic groups, most consumers are planning to spend less over the next 12 months—51 percent of women, 48 percent of working people, 52 percent of rural residents, and 49 percent of middle-income citizens. They are cutting back because they want to balance their budgets and because consumption is now less important to them.

Consumers have started to deemphasize luxury, status, and short-term pleasures in favor of savings, value, health, stability, and family. They are trading down across a wide variety of categories, including jewelry, mobile phones, fast food, paper products, luxury goods, hair care products, personal care, household cleaners, toys and games, and sporting goods. There are now only a few categories in which they are still willing to say, “I want the best.” These include food, travel, appliances, and the home.

Brighter Spots: China and India

It is a different story in China, however. Chinese consumers have optimism, energy, and ambition. In general, they say their world will be bright over the next decade. Our survey points to continued optimism in China’s inland provinces. But in the major coastal cities, recent declines in Western demand for factory goods has led to a flattening of confidence.

Along with the Chinese, Indian respondents feel significantly more secure in their jobs and personal finances than their developed-market counterparts. Fully two-thirds of Chinese and about half of Indians feel confident that they have enough money for a happy retirement. Thirty-nine percent of Chinese respondents told us they are saving more than 20 percent of their income. Significantly, 83 percent of Chinese and 65 percent of Indian respondents believe their children will live better lives than their own—a stark contrast to the developed-market view.

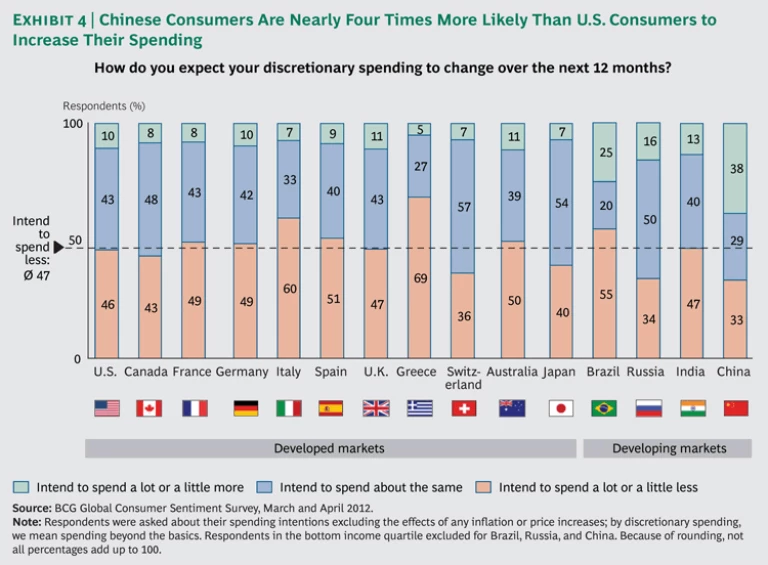

Attitudes in China toward spending and the hunger for trading up remain far more buoyant than elsewhere. An average 38 percent of Chinese respondents say they intend to increase their spending over the next year, up to seven times more than those in developed markets who say the same. (See Exhibit 4.) Over half of Chinese consumers also say they intend to trade up across all the product categories in our survey—more than in any other market (and nearly twice the percentage in India).

Implications for Marketers

Companies should take the following steps to capitalize on the opportunities in today’s challenging economic environment:

- Anticipate a sentiment hangover. Even as the worldwide recession winds down in some countries, consumers—whose income growth and trust in institutions have been threatened—will continue to spend cautiously for some time to come.

- Deliver meaningful innovations that provide technical, functional, and emotional benefits. Consumers will give up their hard-earned discretionary dollars for products that deliver. Stability, health, home, and family have risen on their priority list. Products that can be enjoyed at home will have strong appeal, especially if they offer health and stress-relieving benefits.

- Segment your markets—one strategy won’t serve all. Consumer sentiment and economic conditions vary considerably across countries. De-averaging is key for country-specific pricing plans, cost structures, and brand positioning.

- Focus on value. Companies should be prepared to provide proof of value to cautious consumers and work to broaden that discussion to a more holistic view than just price discounting.

- Prepare for the rise of a new middle class. China and India’s globalizing economies are paving the way for millions of formerly poor consumers to enter the middle class. Carefully designed luxury products that reflect this new status will take a disproportionate share of their income.

Consumers want more value for money, less stress, and more security. They now value stability, home, local products, friends, and spirituality much more than they did just two years ago. They care less about status, fun, and excitement. The cry to companies is help me make ends meet, help me find a way to have simple pleasures, help me save time and save money. Product empathy will become the new watchword. Winning companies will find a way to reach out and deliver.